Muslim conquest of Spain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Muslim conquest of Hispania |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Early Muslim conquests | |||||||||

El Rey Don Rodrigo arengando a sus tropas en la batalla de Guadalete by Bernardo Blanco y Pérez (1871) |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Umayyad Caliphate | Visigothic Kingdom Kingdom of Asturias |

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Al-Walid ibn Abd al-Malik Musa ibn Nusayr Tariq ibn Ziyad Tarif ibn Malik Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa Uthman ibn Naissa |

Roderic † Theodemir Achila II † Oppas (MIA) Ardo Pelagius |

||||||||

The Muslim conquest of Spain was a major invasion of the Iberian Peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal). It was carried out by the Umayyad Caliphate, a powerful Islamic empire, from about 710 to 780. This conquest led to the defeat of the Visigothic Kingdom and the creation of a new Muslim-ruled territory called Al-Andalus.

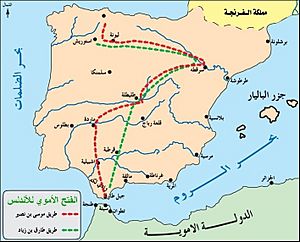

During the rule of Caliph al-Walid I (705–715), a general named Tariq ibn Ziyad sailed from North Africa in early 711. He crossed the Straits of Gibraltar (which are named after him) with about 1,700 soldiers. Their goal was to attack the Visigothic Kingdom, which controlled most of the Iberian Peninsula.

In July 711, Tariq's forces defeated the Visigothic king Roderic at the Battle of Guadalete. After this victory, Tariq received more troops led by his commander, Musa ibn Nusayr. They continued their advance northward.

By 713, a Visigothic count named Theodemir in Murcia surrendered under certain conditions. In 715, Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa became the first governor of Al-Andalus, making Seville his capital. By 717, the Umayyads had even started raiding into Gaul (modern-day France). They captured Barcelona and Narbonne by 719.

The conquest faced challenges, including the Berber Revolt from 740 to 742. In 755, an Abbasid force tried to take control from the Umayyads. However, by 781, Abd al-Rahman I had put down all rebellions. He brought almost all of Iberia under Umayyad rule. This Muslim presence lasted for centuries until the Reconquista, a Christian effort to reclaim the peninsula, intensified in the mid-13th century.

Contents

Why the Conquest Happened

Historians are not completely sure about all the details of what happened in Iberia in the early 8th century. The main Christian record from that time, the Chronicle of 754, is helpful but often vague. There are no Muslim records from that exact period; later Muslim writings were created much later and might have different ideas. This means we should be careful about very specific claims from that time.

The Umayyads took control from the Visigoths, who had ruled the area for about 300 years. When the conquest happened, the Visigothic leaders were having many problems. They struggled with who would be king and how to keep power. This was partly because the Visigoths were a very small part of the population, only about 1-2%. This made it hard for them to control everyone else.

The ruler at the time was King Roderic. It's not clear how he became king. Some stories say he had a dispute with Achila II, the son of the previous king. Later records show that Roderic might have been a usurper, meaning he took the throne unfairly. This suggests there was a civil war happening among the Visigoths.

Reports from Musa ibn Nusayr's early trips to Hispania described "great splendor and beauty." This made the Muslims more interested in invading. During one raid in 710, the Muslims found "rich spoil and several captives, who were so handsome that Musa and his companions had never seen the like of them."

The people living in Hispania saw the Berbers (who were part of the invading forces) as "barbarians" and were afraid of their attacks. In one early raid, a Berber leader "set fire to their houses and fields, and burnt also a church." He killed some people and took others prisoner.

How Al-Andalus Was Established

Conquest and Agreements

According to a later historian, Ibn Abd al-Hakam, the governor of Tangier, Tariq ibn Ziyad, led about 1,700 men from North Africa to southern Spain in 711. People in Spain didn't notice them at first, thinking their ships were just regular trading vessels.

Tariq's forces defeated the Visigothic army, led by King Roderic, in a major battle at Guadalete in July 711. In 712, Tariq's army was joined by more troops from his commander, Musa ibn Nusayr. Musa planned a second invasion. Within a few years, both leaders controlled more than two-thirds of the Iberian Peninsula. Musa's invasion included 18,000 mostly Arab soldiers. They quickly captured Seville and defeated Roderick's supporters at Mérida. Then they met Tariq's troops at Talavera. The next year, their combined forces moved into Galicia and the northeast, taking Léon, Astorga, and Zaragoza.

The first expedition led by Tariq was mostly made up of Berbers. These people had only recently come under Muslim influence themselves. It's possible that this army was continuing a pattern of large raids into Iberia that had happened even before Islam. So, a full conquest might not have been the original plan. Both the Chronicle of 754 and later Muslim sources mention raids in previous years. Tariq's army might have been there for some time before the big battle. Some historians think this is likely because a Berber led the army, and Musa, the Umayyad Governor of North Africa, only arrived the next year. It seems Musa hurried over once the unexpected victory became clear.

The Chronicle of 754 says that "the entire army of the Goths... fled." This is the only record of the battle from that time, and because it lacks details, many later historians made up their own stories. The exact location of the battle is not clear, but it was likely near the Guadalete River.

King Roderic was believed to have been killed. This crushing defeat left the Visigoths without a strong leader and very disorganized. This was partly because the Visigothic ruling class was such a small part of the population. Their government was very centralized, meaning that once the royal army was defeated, the whole land was open to the invaders. This sudden lack of power might have surprised Tariq. It might also have been welcomed by the local Hispano-Roman farmers, who were likely unhappy with the differences between them and the Visigothic rulers.

In 714, Musa ibn Nusayr moved north-west along the Ebro river. He took over the western Basque regions and the Cantabrian mountains, reaching all the way to Gallaecia. There was little or no recorded opposition. During the time of the second Arab governor, Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa (714–716), the main cities of Catalonia surrendered. In 714, Musa ibn Nusayr advanced and took over Soria, western Basque areas, Palencia, and as far west as Gijón or León. A Berber governor was put in charge there with no recorded resistance. The northern parts of Iberia didn't get much attention from the conquerors and were hard to defend once taken. The high western and central sub-Pyrenean valleys remained unconquered.

Around this time, Umayyad troops reached Pamplona. The Basque town surrendered after an agreement was made with Arab commanders to respect the town and its people. This was a common practice in many towns in the Iberian Peninsula. The Umayyad troops faced little resistance. Considering how slow communication was back then, three years was a reasonable time to reach almost the Pyrenees, after making arrangements for towns to surrender and for their future rule.

Scholars believe that unhappiness with Visigothic rule in some parts of the kingdom helped the Umayyad conquest succeed. This included strong disagreements and bad feelings between local Jewish communities and the rulers.

New Government and Taxes

Treaties and Local Rule

In 713, Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa defeated the forces of the Visigothic count Theodemir (also called Tudmir). Theodemir had taken control of southeastern Iberia from his base in Murcia after King Roderic's defeat left a power vacuum. Theodemir then signed an agreement to surrender. His lands became an independent area under Umayyad rule.

This agreement, called the Treaty of Theodemir, shows how Abd al-Aziz (son of Musa) allowed local rulers to stay in power. Theodemir remained in charge as long as he accepted Muslim authority and paid a tax. Abd al-Aziz also agreed that his forces would not attack or "harass" Theodemir's town or people. This agreement covered seven other towns as well.

Theodemir's government and the Christian beliefs of his people were respected. In return, he promised to pay a tax (called jizya) and to hand over any rebels. This meant that for many people, life stayed much the same as before Tariq's and Musa's campaigns. This treaty set an example for all of Iberia. Towns that surrendered to Umayyad troops had similar agreements.

Some towns, like Cordova and Toledo, were attacked and captured without conditions. These were then ruled directly by the Arabs. Mérida also fought against the Umayyad advance for a long time but was finally conquered in mid-712. By 713 (or 714), the last Visigothic king, Ardo, ruled only Septimania and perhaps some eastern Pyrenean and coastal areas.

Islamic laws did not apply to all people under the new rulers. Christians continued to follow their own Visigothic law code. In most towns, different ethnic groups lived separately. New groups arriving (like Syrians, Yemenis, and Berbers) built new neighborhoods outside existing city areas. However, this was not true for towns under direct Umayyad rule. In Cordova, the main church was divided and shared by Christians and Muslims for their religious needs. This situation lasted about 40 years until Abd ar-Rahman's conquest of southern Spain in 756.

Taxes and Administration

An early governor of al-Andalus, al-Hurr ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Thaqafi, spread the rule of the Umayyad Caliphate up to the Ebro Valley and the northeastern borders of Iberia. He brought peace to most of the area and, in 717, began the first raids across the Pyrenees into Septimania. He also started the Umayyad civil administration in Iberia. He sent officials (judges) to conquered towns and lands, which were protected by military bases usually set up near the towns.

Al-Hurr also gave lands back to their previous Christian owners. This likely increased the income for the Umayyad governors and the caliph in Damascus. They did this by applying a tax called vectigalia on specific regions or estates, not per person. Only non-Muslims paid this tax, in addition to the compulsory giving for Muslims (called zakat). The job of setting up a civil administration in al-Andalus was mostly finished by Governor Yahya ibn Salama al-Kalbi 10 years later.

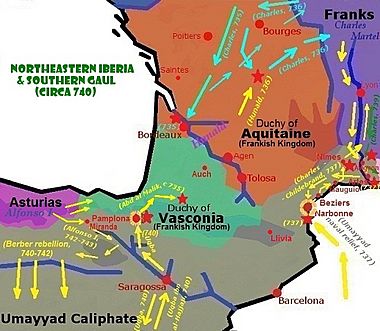

After al-Hurr's time, the Arabs settled in southern Septimania during Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani's time as governor. Narbonne fell in 720. As soon as he had soldiers there, the Arab commander led an attack against Toulouse. During or after this Umayyad push, King Ardo died in 721.

Different Groups and Internal Problems

In the beginning of the invasion, the armies were made up of Berbers from North Africa and different groups of Arabs from Western Asia. These groups, fighting under the Umayyad banner, did not mix much. They stayed in separate towns and neighborhoods. The Berbers, who had only recently become Muslim, were usually given the hardest tasks and sent to the toughest, most rugged areas, similar to their homeland in North Africa. The Arabs settled in the flatter lands of southern Iberia. Important military leaders included Berbers, like Tariq Ziyad, who is known for much of the strategy in conquering Al-Andalus.

Because of this, the Berbers were stationed in places like Galicia (and possibly Asturias) and the Upper Marches (the Ebro river basin). These lands were often unpleasant, wet, and cold. The Berbers felt unfairly treated by their Arab rulers (for example, attempts to tax Muslim Berbers). This led to rebellions in North Africa that spread into Iberia. An early uprising happened in 730 when Uthman ibn Naissa (Munuza), who controlled the eastern Pyrenees, joined forces with the duke Odo of Aquitaine and broke away from Cordova.

These internal disagreements constantly threatened (and sometimes even encouraged) the Umayyad military efforts in al-Andalus during the conquest. Around 739, when Uqba ibn al-Hajjaj heard about Charles Martel's second intervention in Provence, he had to cancel an expedition to the Lower Rhone to deal with the Berber revolt in the south instead. The next year, the Berber soldiers stationed in León, Astorga, and other northwestern outposts left their positions. Some of them even became Christian. After this, Muslim settlements were permanently established south of the Douro river.

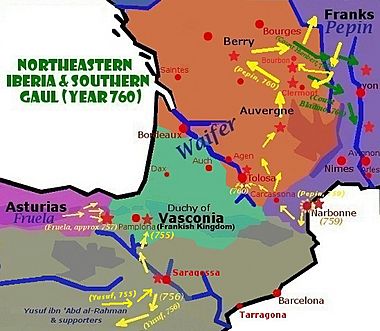

The Berber rebellions swept across all of al-Andalus during Abd al-Malik ibn Katan al-Fihri's time as governor. More soldiers were called in from the other side of the Mediterranean: the "Syrian" junds (who were actually Yemeni Arabs). The Berber rebellions were put down with much bloodshed, and the Arab commanders became stronger after 742. Different Arab groups agreed to take turns ruling, but this didn't last long. Yusuf ibn 'Abd al-Rahman al-Fihri (who was against the Umayyads) stayed in power until he was defeated by Abd al-Rahman I in 756. This led to the creation of the independent Umayyad Emirate of Cordova. It was during this time of trouble that the Frankish king Pepin finally captured Narbonne from the Andalusians in 759.

In the power struggle between Yusuf and Abd-ar-Rahman in al-Andalus, the "Syrian" troops, who were a key part of the Umayyad Caliphate, split up. Most Arabs from the Mudhar and Qais tribes sided with Yusuf, as did the local (second or third generation) Arabs from North Africa. But Yemeni units and some Berbers sided with Abd-ar-Rahman, who was probably born to a North African Berber mother himself. By 756, southern and central al-Andalus (Cordova, Seville) were under Abd-ar-Rahman's control. But it took him another 25 years to gain control over the Upper Marches (Pamplona, Zaragoza, and all of the northeast).

What Happened Next

The Iberian Peninsula was the westernmost part of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruled by the governor of Ifriqiya. In 720, the caliph even thought about giving up the territory. The conquest led to several hundred years where most of the Iberian peninsula was known as al-Andalus, ruled by Muslims. Only a few small Christian kingdoms managed to regain control in the distant, mountainous north of the peninsula.

In 756, Abd al-Rahman I, a survivor of the recently overthrown Umayyad dynasty, arrived in al-Andalus. He took power in Cordova and Seville and declared himself emir or malik. He removed any mention of the Abbasid Caliphs from the Friday prayers. Because of these events, southern Iberia became independent from the Abbasid Caliphate. Abd al-Rahman and his successors believed they were the rightful continuation of the Umayyad caliphate.

During Abd ar-Rahman's rule, before his death in 788, al-Andalus became more centralized and unified. The independent status of many towns and regions, which had been agreed upon in the first years of the conquest, was ended by 778. The Hispanic Church in Toledo, which had kept much of its status under the new rulers, had disagreements with the Roman Church later in the 8th century. Rome relied on an alliance with Charlemagne (who was at war with the Cordovan emirs) to protect its power. Rome then recognized the northern Asturian principality as a separate kingdom from Cordova, and Alfonso II as its king.

Many people in al-Andalus, especially local nobles who wanted a share of power, began to adopt Islam and the Arabic language. However, most of the population remained Christian and used the Mozarabic Rite. Latin (called Mozarabic) remained the main language until the 11th century. Historian Jessica Coope argues that the Islamic conquest was not about forcing everyone to convert to Islam. Instead, it was based on the belief that everyone would be better off under Islamic rule.

Abd ar-Rahman I started an independent dynasty that lasted until the 11th century. After that, many smaller Muslim states (called taifas) appeared. These states could not stop the growing power of the northern Christian kingdoms. The Almoravids (1086–1094) and the Almohads (1146–1173) took over al-Andalus, followed by the Marinids in 1269. But these groups could not prevent the Muslim-ruled territory from breaking apart. The last Muslim kingdom, Granada, was defeated by the armies of Castile and Aragon under Isabella and Ferdinand in 1492. The last major expulsions of Spaniards of Muslim descent happened in 1614.

Timeline of Key Events

Much of the traditional story of the Conquest is more legend than true history. Here are some of the important events and stories:

- 710 – Tariq ibn Ziyad, a Berber leader, lands with 400 men and 100 horses on the small peninsula now called Gibraltar (which means "Mountain of Tariq").

- 711 – Musa ibn Nusayr, Governor of Ifriqiya in North Africa, sends Tariq into the Iberian Peninsula.

- July 19, 711 – King Roderic's army is completely defeated in the Battle of Guadalete in the Guadalquivir valley.

- 712 – Musa ibn Nusayr joins Tariq after the Battle of Guadalete. They attack towns and strongholds that were previously avoided. Abu Zora Tarif lands in Algeciras.

- 713 – Theudimer surrenders under conditions, allowing him to remain lord of his southeastern region around Murcia.

- 715 – Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa is named the first governor of Andalus and marries King Roderick's widow, Egilona. Seville becomes the capital.

- 717–718 – Al-Hurr ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Thaqafi begins the first military campaigns into Gothic Septimania.

- 719 – Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani, the 4th governor, moves the capital from Seville to Cordova. Barcelona and Narbonne are captured.

- 721 – An Umayyad army led by Al-Samh is crushed by Duke Odo's Aquitanian army at the Battle of Toulouse.

- 722 – An Umayyad patrol is defeated by Pelagius at the Battle of Covadonga in the mountains of Asturias.

- 725 – Anbasa ibn Suhaym Al-Kalbi takes control of all Septimania, raids the Lower Rhone, and captures Autun and Sens.

- 731 – Munuza is defeated in Cerdanya by Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi.

- Spring 732 – An expedition led by Governor Al Ghafiqi defeats Duke Odo at the Battle of the River Garonne.

- October 732 – Al Ghafiqi is completely defeated by Charles Martel (a powerful leader in the Merovingian court) at the Battle of Tours.

- 734 – Count Maurontus calls Umayyad forces into Arles, Avignon, and probably Marseille.

- 740–742 – Berbers in northern Iberia (Galicia, Leon, Astorga, upper Ebro) leave their positions to join the Berber Revolts.

- 743–757 – Alfonso I of Asturias raids the territory between the rivers Duero and Ebro but does not keep it.

- 743 – Different Arab groups agree to take turns ruling Al–Andalus each year.

- 747 – Governor Yusuf ibn 'Abd al-Rahman al-Fihri refuses to give up his turn and rules independently.

- 755 – A rebellion in Zaragoza is put down. Yusuf's soldiers are destroyed by the Basques near Pamplona.

- 755 – Abd Al-Rahman Al Dakhel lands on the southern coast, quickly taking Granada, Seville, and Cordova.

- 756 – After refusing to make a deal with Yusuf, Abd ar-Rahman I becomes the independent Umayyad emir of Córdova. Yusuf is defeated.

- 759 – Narbonne is captured by the Frankish king Pepin the Short.

- 763 – A pro-Abbasid army is defeated by Abd ar-Rahman I in Carmona.

- 778 – Charlemagne is pushed back in Zaragoza by local Muslim lords.

- 779 – Abd ar-Rahman I campaigns to the Upper Marches and takes control of its main city, Zaragoza.

- 781 – Pamplona and the Basque lords south of the Pyrenean edges are brought under control. All of Al Andalus is unified.

- 788 – Abd ar-Rahman I dies.

See also

- Timeline of the Muslim presence in the Iberian peninsula

- Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent

In Spanish: Conquista omeya de Hispania para niños

In Spanish: Conquista omeya de Hispania para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |