Rampart Dam facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rampart Dam |

|

|---|---|

An artist's rendition of the proposed dam

|

|

|

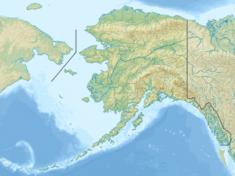

Proposed location

|

|

| Official name | Rampart Dam |

| Location | Interior Alaska, United States |

| Coordinates | 65°21′00″N 151°00′00″W / 65.35000°N 151.00000°W |

| Construction cost | $1.39 billion (1970 est.) |

| Operator(s) | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Impounds | Yukon River |

| Height | 510 feet (155 m) |

| Length | 4,700 feet (1,433 m) |

| Reservoir | |

| Total capacity | 1.145 billion ac·ft (1,412 km³) |

| Catchment area | 200,000 square miles (517,998 km2) |

| Surface area | 9,844 square miles (25,496 km2) |

| Power station | |

| Installed capacity | 5872 MW |

The Rampart Dam was a huge project planned in 1954 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. They wanted to build a dam on the Yukon River in Alaska to create hydroelectric power. This means using the power of flowing water to make electricity.

The dam was planned for Rampart Canyon, which is about 31 miles (50 km) southwest of the village of Rampart, Alaska. It was also about 105 miles (169 km) west-northwest of Fairbanks, Alaska.

If built, the dam would have created a lake as big as Lake Erie. This would have been the largest human-made reservoir (a place to store water) in the world. The dam itself was designed to be a concrete structure 530 feet (162 m) high. Its top would have been about 4,700 feet (1,430 m) long. The power plants would have made between 3.5 and 5 gigawatts of electricity. This amount would change depending on how much water was flowing in the river.

Many politicians and businesses in Alaska supported the project. However, it was eventually canceled because many groups objected. Native Alaskans living in the area protested. They would have lost nine villages that would be flooded by the dam. Groups that protect nature were also against it. They were worried about the Yukon Flats, a huge area of wetlands. This area is a very important breeding ground for millions of waterfowl (birds that live near water). People who believed in saving money (called fiscal conservatives) also opposed the dam. They thought it cost too much and wouldn't help Americans outside Alaska very much.

Because of these objections, United States Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall officially said he was against the dam in 1967. The project was then put aside. Even so, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers finished their study of the project in 1971. The final report was made public in 1979. In 1980, U.S. President Jimmy Carter created the Yukon Flats National Wildlife Sanctuary. This officially protected the area from any building and stopped similar projects from happening.

Contents

Where Was the Dam Planned?

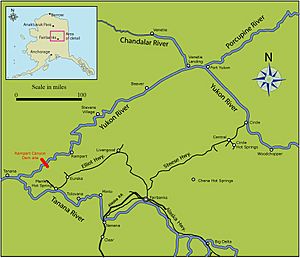

The Yukon River starts in the Coast Mountains. It flows northwest, crossing into Alaska. It then meets the Porcupine River at Fort Yukon. From there, the river turns west and southwest. It flows through the Yukon Flats, which is a low, wet area with many ponds and streams. As the river moves southwest, it meets the Tanana and Koyukuk rivers. Then it loops south, then north, finally reaching Norton Sound in the Bering Sea.

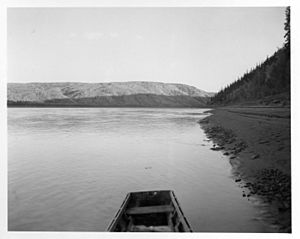

The Yukon River flows through the Central Plateau region of Alaska. In some places, it has cut deep canyons. One of the deepest is Rampart Gorge, also called Rampart Canyon. This gorge is 31 miles (50 km) downstream from the village of Rampart. It is also 36 miles (58 km) upstream from the village of Tanana. It is named after the nearby village of Rampart, Alaska. This village used to be a gold-mining town. Now, it is home to subsistence fishermen, who fish to feed themselves and their families.

At the spot where the dam was planned, the river is 1,300 feet (396 m) wide. Its height is 183 feet (56 m) above sea level. On the south side, the land goes up sharply to a ridge 1,500 feet (457 m) high. North of the river, the land rises to 1,200 feet (366 m). Then it slowly goes up to the Ray Mountains. Under the ground, there are areas of permafrost, which is permanently frozen ground. The area also has earthquakes. A 6.8 Richter Scale earthquake happened there in 1968. Another 5.0 earthquake hit in 2003. The rocks in the area are mostly igneous rock, and you can see quartz in some places.

The part of the river upstream from the dam site drains about 200,000 square miles (517,998 km2) of land. On average, the Yukon flows at 118,000 cubic feet per second (3,341 m3/s) through the canyon. The water flows fastest in late May and early June. It flows slowest after the river freezes over, which happens by early November and lasts until mid-April.

Early Ideas for the Dam

In 1944, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers thought about building a bridge across Rampart Gorge. This was part of a plan to extend the Alaska Railroad from Fairbanks to Nome. The goal was to help send supplies to the Soviet Union during World War II. But the war ended before the bridge plan went very far, so it was dropped.

As early as 1948, U.S. Government officials saw the Rampart area as a good place to make hydroelectric power. Joseph Morgan, from the United States Bureau of Reclamation, wrote a report. He said, "The need for electric power in [Alaska] is growing so fast that new hydroelectric power plants are needed." Morgan's report listed 72 possible sites in Alaska. The Rampart site was one of the few that could make more than 200,000 kilowatts of power.

Morgan wrote about the potential of the site: "Surveys show several possible dam sites in Lower Ramparts. But the best site will probably be found about 31 miles (50 km) downstream from the village of Rampart. ... this site on the Yukon River would easily be one of the biggest potential hydroelectric power projects in North America."

Planning the Project

The first serious look at a dam project happened in 1954. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers studied the resources of the Yukon and Kuskokwim River basin. Engineers thought Rampart Canyon was a great place for a hydroelectric dam. In April 1959, four months after Alaska became a state, Senator Ernest Gruening from Alaska asked the Corps of Engineers to officially study the project. The government gave $49,000 for this study. Early guesses said the project would cost $900 million (in 1959 dollars). It would make 4.7 million kilowatts of electricity. At that time, the biggest hydroelectric project in Alaska was the Eklutna Dam, which only made 32,000 kilowatts.

The Rampart project was competing with a smaller project, the Susitna Hydroelectric Project. That one was planned for south-central Alaska. But because Senator Gruening and others supported Rampart, it became the main focus. The Rivers and Harbors Act of 1960 was passed by the U.S. Congress. It included $2 million to do a full four-year study of the Rampart project. This study would look at how much it would cost and what impact it would have on fish and wildlife. In March 1961, engineers from the Corps' Alaska district started drilling at the site. They wanted to find out how deep the bedrock was and collect other information. To check if the dam made economic sense, the Corps of Engineers created the Rampart Economic Advisory Board (REAB) in February 1961. This board hired a company called Development and Resources Corporation in April to do the study. A team of engineers and REAB members came to Alaska in June to see the Rampart project site. At that time, Senator Gruening thought the project would cost about $1.2 billion to finish.

As the studies continued, the Corps of Engineers made an agreement with the Department of the Interior in March 1962. This agreement said the Corps would design and build the dam. The Interior Department would be in charge of running and taking care of the dam after it was built. During the planning, the Interior Department would also study if the project was worth the money and how it would affect nature. This agreement meant that much of the REAB's work was no longer the main focus. The Interior Department started its own three-year study on the dam's economic and environmental effects. The Development and Resources Corporation still released its report in April 1962. It said the project was good for the economy and would bring new businesses to Alaska. Meanwhile, the Corps of Engineers kept doing their engineering studies.

The Corps of Engineers released a first report in December 1963. It said that building the dam was possible from an engineering point of view. President John F. Kennedy supported the project. He asked for $197,000 (in 1963 dollars) to keep studying it. This money was included in a bill passed by the House of Representatives, and studies continued. The first report gave some numbers about the project's size. The dam would be a concrete structure 530 feet (162 m) high and about 4,700 feet (1,430 m) long. It would raise the Yukon River's height from 215 feet (66 m) above sea level to about 656 feet (200 m). The new lake would be 400 miles (640 km) long and 80 miles (130 km) wide. Its surface area would be bigger than Lake Erie. The power plants would make a maximum of 5 gigawatts of electricity. In total, the planned lake was expected to cover 10,700 square miles (27,700 km2) and hold 1,300,000,000 acre-feet (1,600 km3) of water.

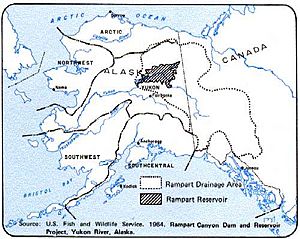

In April 1964, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) released its report. This report was part of the bigger Department of the Interior study. The FWS report was strongly against the dam. It said the dam would completely destroy the Yukon Flats. This area is a very important place where waterfowl breed. In January 1965, the Bureau of Land Management set aside almost 9,000,000 acres (3,600,000 ha) of land for the dam and reservoir. This was a normal process for dam projects. But the huge amount of land caused several months of public meetings before the decision was made.

In June 1964, the Natural Resources Council asked Stephen H. Spurr to lead a group to study the Rampart Dam. Spurr was an expert on forests and nature. His group found that the reasons given for the project were too hopeful. They thought Alaska's population wouldn't grow as much as predicted. They also thought people wouldn't use as much electricity. And they didn't think industries that use a lot of power, like aluminum factories, would move to Alaska as quickly.

Also, the dam would have greatly reduced the number of five types of Pacific salmon. This included chinook, chum, and coho salmon. It would also get rid of huge numbers of migrating waterfowl. This included an estimated 1.5 million ducks and 12,500 geese that flew to the Yukon Flats every year. There would also have been a sharp drop in large animals like moose, black and grizzly bears, and caribou. Smaller animals like muskrats, mink, beavers, and river otters would also be affected. And animals like marten, wolverines, weasels, lynx, snowshoe hares, red fox, and red squirrels would also suffer. Spurr's report said: "If animals are forced to leave their normal homes, it's like getting rid of them completely. Nearby areas usually already have as many animals as they can support. So, losing their home means losing the animals that live there."

In March 1966, Spurr's team released its final report. It said that the dam was not a good investment for the money.

In January 1965, the Department of the Interior finished its 1,000-page study of the Rampart project. It included the Fish and Wildlife study from 1964. It also had studies on how the dam would affect the Alaska Native people in the region. United States Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall then created a special group to look at all the findings before he made a final decision. Throughout 1965 and 1966, groups for and against the project paid for their own studies. These studies aimed to support or reject the arguments for the dam.

In June 1967, the Department of the Interior gave its final advice. It suggested that the dam should not be built. Secretary Udall mentioned the loss of fish and wildlife. He also said there were cheaper ways to get power. And he noted that the dam would not create any fun activities for people.

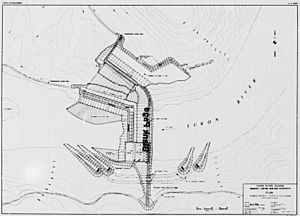

Why the Dam Was Canceled

Even though the Interior Department said no to the Rampart Dam, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers kept studying how to build it. Their plan was finished on June 25, 1971. It included most of the earlier government papers about the project. This included studies on the need for electricity from 1965, the Fish and Wildlife study from 1964, and other studies about whether the project was worth the money. It also had a detailed description of how to build the dam and the overall plan. Reports about the area's land and water were also included. The report was two books long, with over 480 pages. Because building could only happen for five months each year, the Corps of Engineers thought it would take many decades to build the dam.

How It Would Be Built

Since there were no roads to the dam site, the first step would have been to build a temporary road. This road would go from Eureka, about 30 miles (48 km) away, to the dam site. They also thought about extending the Alaska Railroad from Fairbanks to the site. It would take about four years for planning before building started. This included detailed surveys and finishing the design of the dam, powerhouse, and other buildings. Engineers thought that after four years of planning, it would take three more years to dig tunnels to move the river and build cofferdams. Cofferdams are temporary walls that keep water out so workers can build in the dry streambed. Homes and offices for workers would also be built on the south side of the site. The cost for all this was part of the total cost.

Building the dam would start after the river was moved, in the seventh year of the project. The first concrete would be poured in the eighth year. Work on the powerhouse would begin in the 11th year. The lake would be very big, so engineers thought the river tunnels would be closed in the 13th year. This would let the new lake start filling up as construction continued. The lake would reach a certain height in the 21st year. The dam would be finished in the 25th year. The lake would be completely full in the 31st year after the project started. Power generators would be put in as needed, with the last one planned for the 45th year of the project.

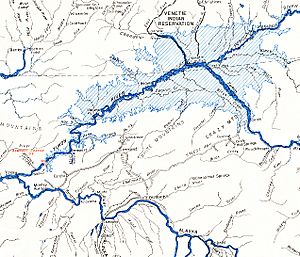

The dam would be a concrete structure 510 feet (155 m) high. At its top, it would stretch for 4,700 feet (1,430 m) from north to south. On the south side, there would be a concrete spillway (a channel for water to flow over) with a crest at a certain height. It could handle a lot of water flowing over it. The power plants would have twenty-two large units and two smaller units.

Building the dam would need a huge amount of materials. This included 15,000,000 cubic yards (11,470,000 m3) of concrete mix, 2,900,000 cubic yards (2,220,000 m3) of rock, and another 1,700,000 cubic yards (1,300,000 m3) of other materials. Engineers thought some materials could be found at the site. But the rest would have to be brought from other places.

The Planned Lake

If the lake reached its planned height, it would hold a total of 1,145,000,000 acre-feet (1,410 km3) of water. The full lake would be about 270 miles (435 km) long and 80 miles (129 km) wide. The lake would have about 3,600 miles (5,800 km) of shoreline. Its total surface area would be about 9,844 square miles (25,496 km2). Because the Yukon River is also used for transportation, there were plans for places to transfer goods below and above the dam. These would be connected by roads and train tracks. Because the planned lake was so big, and because some water needed to flow downstream for river travel and fishing, engineers thought it would take at least 16 years to fill the lake.

How Much Would It Cost?

The Rampart Dam was very large, so it had a very large price tag. The Corps of Engineers expected to spend $618.4 million (in 1970 dollars) just to build the dam itself. Another $492 million would be for the power-generating equipment. The total cost was estimated at $1.39 billion. This total included $15.59 million to move Alaskans from the area that would be flooded. It also included $56 million for facilities to help fish and wildlife, to make up for the expected losses. And $39.7 million was for roads and bridges to get to the area. After the dam was built, the Corps of Engineers thought it would cost $6.5 million each year to run and maintain it. This included money for new power equipment and for maintaining the fish and wildlife facilities.

Weather Changes

From the very beginning, people who supported and opposed the dam wondered if the huge lake it would create could change the weather in Interior Alaska and the Yukon. Several studies were done about these possible changes. Most reports thought the weather would be similar to what happens around Great Slave Lake and Lake Baikal. These lakes are similar in size and location. Forecasts predicted the lake would hold heat longer in the fall. This would keep temperatures in the area slightly warmer than normal. In the spring, however, the area around the lake might get more rain or snow. This is because of something called lake-effect snow. In the summer, the long daylight hours would make the land around the lake warmer than the lake itself. This could also cause storms.

Who Supported the Dam?

Many different groups supported the dam project. They usually used three main reasons:

- The electricity from the project would be cheap and plentiful.

- Businesses would be attracted to Alaska because of the cheap electricity.

- Building the dam would not harm the environment or people too much.

During the campaign for the 1960 U.S. Presidential election, both candidates, Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy, visited Alaska. Both men supported the Rampart Dam project. Kennedy said, "I see the greatest dam in the free world at Rampart Canyon. It will produce twice the power of the Tennessee Valley Authority to light homes and mills and cities and farms all over Alaska." Nixon, who arrived three months after Kennedy, said, "You can expect progress, more progress, I believe, in our administration than his."

Leaders of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers strongly supported the project at first. In 1960, Harold Moats from the Corps' Alaska district said, "Rampart Canyon, the big one, is Alaska's most valuable resource. As it is developed, Alaska will take her rightful place in the family of states. She will contribute richly to the economy of the nation and the well-being of the whole free world."

In early September 1963, a group of Alaska businesspeople and local government leaders met. They wanted to organize efforts to get the dam built. The group was called the Yukon Corporation for Power for America, later shortened to Yukon Power for America, Inc. The group started with $100,000. They used this money to create "The Rampart Story," a colorful brochure. It was given out in Alaska and Washington, D.C., to promote the dam project.

Alaska Senator Ernest Gruening was a strong supporter of the project from the start until it was canceled. He made it a very important personal goal. Gruening led a group of Alaska lawmakers, including most of the Alaska Legislature. In the 1962 Alaska state elections, every person elected to the state legislature supported the project. In the years that followed, the Alaska Legislature voted many times to give state money for the project. City politicians also got involved. The city of Anchorage and the Fairbanks Public Utilities Board each voted to give $10,000 to a group that supported Rampart. Among the group's members was Ted Stevens, who later became one of Alaska's U.S. Senators in 1968.

The Electricity Argument

The dam was planned to produce about 34 terawatt hours of electricity each year. This was nearly 50 times the total energy used by all of Alaska in 1960. Senator Gruening believed the dam would have a similar effect to the Tennessee Valley Authority in the 1930s. He thought cheap electricity would be the base for the region's economy. Dam supporters also suggested that the electricity could be sent to the rest of the United States. This would lower electricity prices in those states by increasing the amount of power available. Anthony Netboy, a salmon biologist who worked for Yukon Power for America, even claimed that one day, "a housewife in Phoenix or L.A. will fry her eggs at breakfast with electricity generated on the far-off Yukon."

The Industry Argument

Supporters of the project thought that the cheap electricity from the dam would attract industries that use a lot of power. For example, aluminum smelting (making aluminum) could move to Alaska. They were encouraged by a 1962 study that said the electricity would attract aluminum, magnesium, and titanium industries. It also said it would help process minerals found in the area. The report also stated that the dam would attract a wood pulp mill. This mill would process hundreds of millions of board feet of timber that would otherwise be lost when the dam's lake flooded. The authors of the report even predicted that 19,746 jobs would be created by the dam's construction. This did not even include jobs created during the building process. Both the 1962 study and another report in 1966 said that tens of thousands of jobs would be created just by building the dam. This would happen even if the cheap electricity didn't attract any other businesses to Alaska.

The Impact Argument

When the Rampart Dam was being considered, Alaska, especially Interior Alaska, had very few people. The 1960 United States Census showed only 226,127 people living in Alaska. This made it the least populated state at the time. Interior Alaska had about 28,000 residents. Supporters of the dam said that the benefits of the dam would be much greater than the costs to the few people who would have to move. A staff member for Senator Gruening once said the area to be flooded was worthless. He claimed it had "not more than ten flush toilets." He added that it would be hard to find another area in the world where so little would be lost by flooding. In a 1963 letter, Gruening wrote about the 2,000 Athabascan Native Alaskans: "They could not but be better off than they are now. Their villages are flooded sometimes by the Yukon. Their homes are poor, and they barely make a living, sometimes needing help. Building the Rampart Dam will give them plenty of good jobs. In their new homes, chosen by them on the lake's edges, they will have better houses, better community services, and a steady income from new activities created by the lake."

In the same letter, Gruening also said the dam could create a thriving tourism industry in Interior Alaska. Other dam supporters also brought up this idea. Gruening said the project would be like Lake Powell. It would create many fun activities, like water skiing and picnicking.

Who Opposed the Dam?

Opposition to the project came from three main reasons:

- Ecological: It would harm nature.

- Human: It would force people to move.

- Financial: It cost too much money.

Conservation groups were against the dam because it would flood the Yukon Flats. This is a large wetland area that is a breeding ground for millions of waterfowl. It also provides homes for game and fur-bearing animals. Alaska Native groups objected to the human cost. More than 1,500 people and 9 villages would have to move. Native groups outside the lake area were also worried about the possible destruction of the Yukon River salmon population. The third objection was about the dam's high cost. Many believed that cheap electricity would not be enough to attract businesses to Alaska.

Ecological Objections

In late 1960, the Alaska Conservation Society was the first big conservation group to oppose the dam. They believed flooding the Yukon Flats would cause serious damage to Alaska's waterfowl. They suggested the smaller Susitna Hydroelectric Project instead to provide Alaska's electricity. In early 1961, the Alaska Sportsmen's Council also criticized the Corps of Engineers. They said the Corps was reducing money for studies on how the project would affect fish and game. In April of that year, Alaska Sportsman magazine officially opposed the project.

The California Fish and Game Commission was one of the first groups outside Alaska to oppose the dam. In 1963, they said it would flood the Yukon Flats. This area is one of North America's largest waterfowl breeding grounds. After that, other groups started to organize at the 1963 North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference. Fifteen conservation groups put together $25,000 at the meeting. They used this money to start their own scientific study of the project and begin a campaign against it.

In the spring of 1964, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service released a report on the dam's impact on the Flats. The report strongly opposed building the dam. It said, "Never before in the history of water projects in North America have the losses to fish and wildlife from one project been so huge." The report also pointed out the danger the dam would pose to the Yukon River's large salmon population. These salmon swim upstream every year to lay their eggs. Arthur Laing, Canada's minister of northern affairs, also worried about the possible loss of waterfowl. He was also concerned about the threat the dam posed to Canada's part of the Yukon River salmon population.

A May 1965 article in The Atlantic magazine by Paul Brooks showed the growing protests from conservationists. After traveling the Yukon River, Brooks thought building the dam would be a disaster for nature and people. He also thought it would cost too much money. And he believed the claims about attracting industry and tourism to Alaska were greatly exaggerated. He estimated that building the dam would destroy the homes for 1.5 million ducks, 12,500 geese, 10,000 cranes, 270,000 salmon, 12,000 moose, and seven percent of Alaska's fur-bearing animals. Similar articles appeared in magazines like Field and Stream, which called the project "a catastrophe of major proportions." The Audubon Society Magazine said the dam "would undo 30 years of effort in waterfowl preservation." Even the sports magazine Sports Illustrated asked if the cost of so many waterfowl would be worth building the dam.

Human Objections

When planning the dam, engineers expected that building it would flood nine Alaska Native villages. This would force about 1,500 people to move. Some villagers felt that the new job opportunities would be worth moving. But most objected to losing the region's history. One of the affected villages was Fort Yukon, which is the oldest English-speaking settlement in Alaska. In 1964, several groups of Native dam opponents in the Yukon Flats formed an organization called Gwitchya Gwitchin Ginkhye. This group worked against the project. The Tundra Times, an Alaska newspaper about Native issues, also strongly opposed the project. It said that all but one village from the beginning of the proposed lake to the mouth of the Yukon River were against the dam. Don Young, Alaska's representative to the U.S. House of Representatives, was elected to the Alaska Legislature in 1964 from Fort Yukon. His main promise was to oppose the Rampart Dam.

A survey of the old human and animal remains in the Yukon Flats was done in 1965. It objected to the possible loss of the area. It said that the area had great potential for finding old human history. It added that difficulties in fieldwork would need to be overcome to avoid losing what might be some of the most important prehistoric records in North America.

The Canadian government also strongly opposed the Rampart Dam project. According to the Treaty of Washington, signed in 1871, Canada was allowed to use the Yukon River freely for boats. It was feared that building the dam would block boat routes and break this treaty.

Financial Objections

Opposition to the dam project also came from worries about its cost. Several United States congressmen and fiscal conservatives protested the idea. They argued that the money spent on building the dam would be better used for other projects. They pointed out that there was not much existing infrastructure (like roads or buildings) in the region. They said it was unlikely that enough electricity from the dam could be sold at a high enough price to pay for its construction.

In his 1966 study of the project's economic feasibility, Michael Brewer disagreed with the conclusions of the 1962 government study. He said that the dam's ability to pay for itself was "just guessing." He also wrote that even if the dam was built and cheap electricity was available, "Alaska did not have a competitive advantage." He concluded by saying that the project was "not economically efficient." Because of arguments like these, many informed people outside Alaska believed the project was designed only to benefit Alaska. They almost saw it as "foreign aid." An editorial in The New York Times summed up opinions outside Alaska when it asked if the dam project was "the world's biggest boondoggle" (a wasteful project).

The End of the Project

Because of growing public pressure, in June 1967, United States Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall announced he was strongly against the dam. He mentioned economic and biological reasons, as well as the huge impact on the area's Native population. Even though this effectively ended the project, planning continued until the final Army Corps of Engineers report was released in 1971. This report recommended the project "not be undertaken at this time." Alaska governor William Allen Egan protested this statement. He said the report was outdated because Alaska's population had grown and the demand for electricity was rising.

The report was looked at again. But in 1978, the Army Corps of Engineers confirmed that the project was no longer justified. The reviewed report was accepted by the U.S. Senate, and no more money was given to study the issue. The final end came on December 1, 1978. President Jimmy Carter approved the creation of the Yukon Flats National Wildlife Monument. This later became the Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge in 1980. The refuge status meant that the Yukon Flats could not be flooded. This flooding would have happened if the dam had been built.

In summer 1985, the last parts of the dam project were removed. The 8.96 million acres (36,300 km2) of land that had been set aside for the dam were released by the Bureau of Land Management for other uses.

What We Learned from Rampart Dam

The arguments around the Rampart Dam project showed how the environmental movement was changing in the 1960s. Before, it mostly focused on saving the natural beauty of places, which led to the creation of the U.S. National Park Service. But during the 1960s, nature lovers and environmentalists also started to think about the human cost of building projects. While opposition to Rampart was mainly about money and nature, its effects on the Alaska Native people in the region reflected later worries about building projects in cities too.

Among Alaska Natives, the Rampart Dam project encouraged them to organize and connect with different communities and tribal groups. When the Trans-Alaska Pipeline was suggested in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Native organizations that had formed to oppose Rampart Dam came back to oppose the pipeline. The pipeline only moved forward after Native land claims were recognized in the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

Images for kids

-

An architectural drawing of the final Rampart Dam plan by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

-

A map of the proposed Rampart reservoir drainage basin from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service report against the dam.