Regencies on behalf of Isabella II of Spain facts for kids

Isabella II of Spain was born on October 10, 1830. She was only three years old when her father, Ferdinand VII of Spain, died on September 29, 1833. Because she was so young, her mother, Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies, became her first regent. Later, General Baldomero Espartero took over. This period, known as Isabella's minority, lasted almost ten years. She was declared old enough to rule on July 23, 1843.

When King Ferdinand VII died, his wife Maria Christina quickly became regent for Isabella II. She promised to lead Spain differently, moving towards more liberal ideas. Many people in Spain hoped for changes that would bring the country closer to other European nations. However, the First Carlist War began, and there were fights between different liberal groups. This led to General Espartero taking charge during a time of many government problems and social unrest.

Contents

Europe's Changing Times

In Great Britain, William IV started many liberal reforms. The Parliament became very powerful. After Spain's defeat in the Battle of Trafalgar, the British Empire grew, especially from 1837 when Queen Victoria became queen. Democracy became the accepted way of governing.

On the European continent, absolutism was fading. In 1830, France overthrew its absolute king, Charles X. A constitutional monarchy was set up with Louis-Philippe d'Orleans as king. During his rule, the Industrial Revolution began, and the middle class (called the bourgeoisie) gained control of the economy.

Absolute rule was still strong in Prussia, Russia, and Austria. But even in Prussia, liberals pushed for change. They helped create the German Customs Union, which opened borders and helped new industries grow.

The First Carlist War

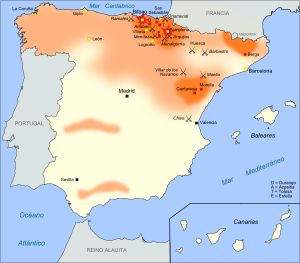

The death of Ferdinand VII caused many uprisings. His brother, Don Carlos, was declared king by his supporters. These uprisings were led by military men who supported absolute rule. A bloody civil war began, mainly in the Basque Country and Navarre. There were also smaller fights in Catalonia, Aragon, and Valencia.

Who Fought in the War?

The First Carlist War was a fight to decide Spain's future. Would it keep the old ways (the Ancien Régime) or become a liberal country?

Carlists wanted to keep absolute rule. Their supporters included rural nobles, some clergy, and peasants from the Basque and Navarrese regions. They fought under the slogan "God, Country and Fueros." Fueros were special local laws and rights.

The liberals were led by Queen Regent Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies. At first, they were moderate, but later, more progressive liberals joined. Educated middle-class people who wanted to end the old system supported the liberals.

How the War Happened

Carlist uprisings started in 1833. When Don Carlos returned to Spain in 1834, he tried to set up his own government in the Basque Country and Navarre. The Carlists used guerrilla warfare tactics. They knew the countryside well, while cities were mostly liberal. The war was a fight between rural and urban areas, lasting three stages:

- Stage 1 (1833-1835): This stage was led by the Carlist commander Zumalacárregui. The liberal army struggled against the guerrillas. Queen Maria Christina had to call on the progressives for help. In 1835, Don Carlos wanted to attack Bilbao, but Zumalacárregui disagreed. The attack failed, and Zumalacárregui died.

- Stage 2 (1835-1837): Cabrera replaced Zumalacárregui. Both sides tried to gain control. The liberal general, Luis Fernández de Córdoba, tried to create a defense line to cut off the Carlists. But the area was too large to cover. The Carlists tried to expand their fight to Catalonia and Aragon, but they failed. The war mostly stayed in the Basque Country and Navarre.

- Stage 3 (1837-1839): By 1837, it was clear the liberals were winning. The Carlists became divided. Some wanted to surrender, while others wanted to keep fighting. Finally, General Maroto signed the Convention of Vergara with the liberals in August 1839. This ended the war. The agreement also allowed Carlist soldiers to join the royal army and kept some of the Fueros.

General Espartero gained a lot of fame from this war. He became known as the "Sword of Luchana" and received a noble title. Maria Christina continued to rule as regent until 1843. That year, Princess Isabella was declared old enough to rule at age thirteen.

Maria Christina's Time as Regent

Early Governments

In 1832, Francisco Cea Bermúdez became the head of government. He was a moderate and made small administrative changes. But he didn't do enough to bring liberals into the new system. One important reform was a new division of Spain into provinces. This was done to improve administration and is still mostly in place today. Because of the lack of progress, Maria Christina replaced Cea Bermúdez with Francisco Martínez de la Rosa in January 1834.

Martínez de la Rosa faced the Carlist War. He tried to reform the clergy and introduced the Royal Statute in 1834. This document tried to blend liberal ideas with the old system. It didn't clearly state if power belonged to the King or the Cortes. This made neither side happy. Tensions grew, especially during a cholera epidemic. Rumors spread that the Church had poisoned water, leading to attacks on convents. Martínez de la Rosa resigned in June 1835.

The Royal Statute of 1834

The Carlist War forced María Christina to change how Spain was governed. To stay on the throne, she had to give some power to the liberals. This was a big step towards liberalism in Spain.

After King Ferdinand VII died in 1833, Maria Christina appointed Francisco Martínez de la Rosa to lead a moderate liberal government. His job was to create a new political framework. The progressives didn't fully support Martínez de la Rosa. However, his appointment was a big change because the monarchy was giving up some of its absolute power. The Royal Statute was also a way to thank the liberals for their support during the war.

In practice, the Royal Statute gave the Crown a lot of power. The Queen directly appointed many members of the Cortes. Only the richest people could vote for the other members. The Queen held executive power, and legislative power was shared with the Cortes. Liberals were disappointed by how few changes were made.

The Royal Statute created two chambers in the Cortes. One was the Estamento de Próceres (House of Peers), where non-elected representatives like Grandees of Spain sat. The other was the Estamento de Procuradores, where deputies were elected by only about 16,000 men. The Cortes could vote on taxes but needed the Crown's support to propose new laws.

Progressives found ways to push for more reforms. The liberals' poor performance in the early Carlist War forced Maria Christina to make more concessions. Progressives helped approve individual rights like freedom, equality, property, and judicial independence. By 1835, they had pressured Maria Christina to appoint a progressive liberal government.

Liberals Gain Power

Progressives came to power through revolts in the summer of 1835. These were led by local councils (Juntas) and militias. With the country in chaos, the Queen Regent had to appoint a progressive government. Juan Álvarez Mendizábal became the leader. He quickly started reforms to modernize Spain.

Mendizábal's main goal was to get money for the liberal army and to pay off the government's debt. His solution was to sell off Church property, a process called confiscation. But powerful groups opposed this. They pressured Maria Christina to fire Mendizábal. She did, but another uprising in 1836, the Mutiny of La Granja, forced her to bring a progressive government back. Mendizábal returned as Minister of Finance.

Progressive Reforms (1835-1837)

Mendizábal was a key figure. He had lived in exile in Europe and learned about liberal ideas. He believed that to make Spain a liberal country, they needed to:

- End the old feudal system (seigniorial regime).

- Break up large family estates (ending majorat).

- Sell off Church and civil properties (confiscation).

This would lead to an agricultural revolution, creating wealth to invest in industry.

The old feudal system was abolished in August 1837. Lords lost their power over people but kept their land if they could prove ownership. Large family estates were also broken up, allowing many nobles to sell land and improve their finances.

The most important reform was the Church confiscation. Mendizábal used a special law to make quick decisions for the war. He issued decrees to reform the regular clergy. The first decree in February 1836 closed down most male religious orders. Only missionary and hospital orders were saved. For female orders, convents were closed, and limits were placed on the number of nuns. All property from these orders became national property.

The second decree in March 1836 allowed the sale of these national properties. Mendizábal argued this would solve the government's debt problem. It would also promote a free market and create a group of people who supported Isabella's cause. The properties were sold through public auction, meaning only the richest could buy them. This helped pay off the public debt.

These reforms also included laws to support a free market. This meant freedom in farming, free movement of goods, and ending the rights of the Mesta (a powerful sheep herders' guild). Farmers could fence their lands, and prices were set by supply and demand.

Liberals felt strong and held protests across Spain. The progressive press criticized the government and pushed for a more democratic system. However, the Regent offered the government leadership to José María Queipo de Llano. He resigned after three months due to violent clashes in Barcelona and revolutionary uprisings. These groups, called juntas, joined the National Militia and took control of provinces. They demanded more power for the Militia, freedom of the press, and more people being allowed to vote.

Maria Christina had to give the government to Mendizábal. He agreed to dissolve the revolutionary juntas if they were integrated into the state. He also promised political and economic reforms. He gained special powers to reform the public treasury and tax system. This was to ensure the state could pay its debts and get new credit. He also continued the confiscation of Church assets to bring unproductive goods into the market.

Mendizábal also planned to reorganize the army, changing top commanders who were too traditional. He increased the army to 75,000 men and gave more money to the Carlist War. But the Regent didn't like losing authority over the army. Mendizábal was dismissed. Francisco Javier de Istúriz, a progressive who had become more moderate, became president. He tried to create a more conservative constitution. But the Mutiny of La Granja de San Ildefonso stopped him. This mutiny demanded the return of the Constitution of 1812. Istúriz resigned in August 1836.

The new president was José María Calatrava. He appointed Mendizábal as Minister of Finance. They finished the confiscation process and ended the tithes (Church taxes). Calatrava also approved Spain's first law recognizing freedom of the press. But his most important work was adapting the Constitution of 1812 to the new reality. This led to the Constitution of 1837.

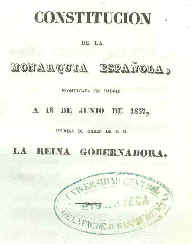

Constitution of 1837

After the Mutiny of La Granja, the progressive government created a new constitution. This was the Constitution of 1837. It aimed to be a compromise between progressives and moderates. It created a constitutional monarchy where the Crown's power was strengthened. The constitution stated that power came from the nation, not just the Crown.

The Constitution of 1837 set up a two-chamber Cortes:

- The Senate: Members were appointed by the Queen.

- The Lower House: Members were elected by census suffrage (only rich men could vote).

The Crown could dissolve the Cortes and veto laws. The Crown was the most powerful part of the state, but its powers were limited by the Cortes. The text also protected individual rights like freedom of the press.

Historians have debated why the progressives created this constitution. Some believe they wanted to end the political fighting between progressives and moderates. Others think they didn't dare to propose a system other than a constitutional monarchy. A third idea is that both parties were similar, only differing in how fast they wanted reforms. They all wanted a capitalist society with a free market.

A big problem for liberalism was Spain's economic struggles. The middle class was weak. Liberals faced enemies from both the absolutist right and the social revolutionary left. They wanted to protect what they had achieved. Both progressives and moderates agreed that a strong executive power was needed. They chose to strengthen the Crown, but they wanted a king they could control.

Carlists Near Madrid

The Constitution was written while the Carlists had taken Segovia and were close to Madrid. Since 1833, the Carlists had been at war against the Christinos (supporters of Isabella). They were strong in the Basque Country, Navarre, and Catalonia.

Don Carlos escaped his exile and settled in Navarre and the Basque Country. He directed the conflict from there, making Estella his capital. After some early successes, the Carlist general Zumalacárregui died during the siege of Bilbao in June 1835. This led to a more stable front line.

General Baldomero Espartero led the troops loyal to the Regent. He stopped the Carlist advance towards Madrid in 1837. On August 29, 1839, he signed a peace agreement with the Carlist general Rafael Maroto. This was known as the Abrazo de Vergara (Embrace of Vergara).

Political Groups

The Progressive Party believed that national power belonged only to the Cortes Generales. They did not want a Republic. They organized a National Militia, which moderates disliked. Economically, they supported Mendizábal's ideas: confiscation of Church lands, ending large family estates, and free trade.

In 1849, the Democratic Party formed. They wanted universal manhood suffrage (all men voting), not just the rich. They also wanted to legalize early worker organizations and ensure fair land distribution for farmers.

The moderates saw themselves as protecting the monarchy and the old system from radical liberals. Their members were mostly nobles, high officials, lawyers, and clergy. They believed national power should be shared between the King and the Cortes, based on "historical rights."

The Moderate Years (1837-1840)

After Calatrava's government, three moderate liberals became president in less than a year. The first was Eusebio Bardají Azara. He resigned because he was unhappy with the Regent trying to gain Espartero's support. He was followed by Narciso de Heredia and Bernardino Fernández de Velasco.

On December 9, 1838, Evaristo Pérez de Castro became president. He made reforms in local government that allowed some state control. He also tried to improve relations with the Holy See (the Pope), who was suspicious of the Spanish Crown.

The "Revolution of 1840" and Maria Christina's End

The idea of peaceful power changes between moderates and progressives failed. The moderate government of Evaristo Pérez de Castro proposed a new Local Government Law. This law would let the government choose mayors from elected councilors. Progressives said this went against the Constitution of 1837. They protested, even invading the Congress of Deputies. When the law passed, they left the Chamber, questioning the Cortes' legitimacy.

Progressives then campaigned for Maria Christina not to sign the law. They threatened rebellion if she did. They asked General Baldomero Espartero, the most popular figure, to stop the law. Progressives feared this law would make it impossible for them to win elections. It would also put the National Militia, which they saw as protecting people's rights, under moderate control.

The Regent knew the system was in trouble. She went to Barcelona with Isabella and met with Espartero. Espartero demanded that Maria Christina not sign the Local Government Law. But on July 15, 1840, she signed it. Espartero then resigned from all his positions. Pérez de Castro's government resigned on July 18. After three short-lived governments, another moderate government took over on August 28.

In Barcelona and Madrid, fights broke out between moderates and progressives, and between supporters of the Regent and Espartero. Maria Christina moved to Valencia. Espartero tried to appear to defend the Regent by declaring a state of siege in Barcelona, but it was lifted later.

From September 1, 1840, progressive revolts spread across Spain. "Revolutionary juntas" formed, challenging the government. The Madrid junta published a statement saying they were defending the threatened Constitution of 1837. They demanded the Local Government Law be stopped, the Cortes dissolved, and a new progressive government.

Maria Christina ordered General Espartero to stop the rebellion. He refused. The Regent had no choice but to accept a new government led by General Espartero and composed of progressives. Their plan included suspending the Local Government Law, dissolving the Cortes, and Maria Christina resigning as Regent. The letter to the Regent hinted at her secret marriage to Agustín Fernando Muñoz y Sánchez, which happened three months after King Ferdinand VII died. Maria Christina realized she had lost all authority. She resigned from the Regency on October 12, 1840, asking Espartero to take over.

Espartero's Time as Regent

When General Espartero came to power after the "revolution of 1840," it was the first time a military man led Spain. This became common in the 19th and 20th centuries.

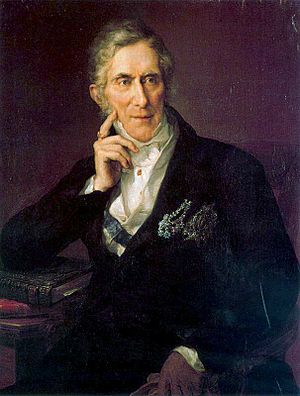

How Espartero Became Regent

Espartero's regency was shaped by two events: Maria Christina's removal in 1840 and Princess Isabella becoming queen in 1843. This was a progressive period, with the Constitution of 1837 still in use. Espartero, born in the late 18th century to a humble family, joined the army during the War of Independence. He quickly rose through the ranks in America.

He returned to Spain with a good reputation but no wealth. His marriage to an aristocrat, Jacinta Martínez Sicilia, helped him join high society. When the First Carlist War began, Espartero joined the liberals. He became commander of the northern armies in 1836. His victory at Luchana earned him the title Count of Luchana. Maria Christina relied on him for war matters. His success in signing the Convention of Vergara in 1839 earned him another title: Duke of la Victoria.

In 1840, the progressive party made him the new regent until 1843. Later, from 1854 to 1856, he was prime minister. In the 1860s, he retired. After Isabella II was dethroned, some liberals offered him the throne, but he refused. Amadeo later gave him the title Prince of Vergara.

After Maria Christina was removed, there was a debate about whether one person or three people should be regent. The more radical progressives wanted three regents to limit the head of state's power. Espartero became the sole regent thanks to moderate senators.

Espartero's Rule

As regent in 1841, Espartero continued reforms from 1837. He kept up the confiscation of Church property, including secular clergy lands and Church taxes (the tithe). This caused a break in relations with Rome (Pope Gregory XVI). Espartero became isolated in Europe, only supported by England.

His second reform was about the Foral Question. A law was passed to remove the fueros (special local laws). This angered the Carlists, who had signed peace on the condition of keeping their fueros. It also led to plots by moderate military officers who allied with the Carlists.

Espartero's reforms led to constant conflict from 1842 to 1843. He faced three main groups of opponents:

- Moderate plots: These were supported by Maria Christina. In October 1841, there was an uprising in the Basque Country and Madrid. Diego de León tried to kidnap Princess Isabella from the royal palace. The plan failed, and Diego de León was executed. Other moderate uprisings continued to fail until 1843. Key plotters were General Leopoldo O'Donnell and General Narváez.

- Barcelona uprisings: In late 1841 and early 1842, there were revolts in Barcelona. These were caused by a free trade agreement with England that hurt the Catalan textile industry. These uprisings were democratic and republican. Espartero declared a state of siege and bombed the city in 1842. This greatly reduced his popularity.

- Opposition from his own party: Civilian progressives, led by figures like Manuel Cortina and Salustiano Olózaga, criticized Espartero. They accused him of being too pro-English, authoritarian, and wanting to become king.

This opposition weakened Espartero. In May 1842, his government lost a vote of no confidence. In 1843, Espartero's regency ended. Joaquín María López came to power and tried to reform the constitution to create a parliamentary monarchy. Espartero didn't agree, and López resigned. In the summer of 1843, a military uprising against Espartero began. Progressive civilian leaders, moderates, and Carlists all joined. General Narváez benefited most, becoming head of government.

The moderates called elections and won. The Cortes declared Princess Isabella old enough to rule at 13. She began her personal reign.

Taking on the Regency

To gain power, Espartero relied on the "revolutionary juntas" from the "revolution of 1840." But the way he took power caused divisions among progressives. Some wanted a Central Junta to decide how the government would be organized. Once Espartero's government formed, those who wanted a Central Junta argued for a three-person regency to limit Espartero's power. Those who supported Espartero as the sole regent were called "unitarians."

Espartero officially became regent on May 8, 1841, with the support of the "unitarians." Before that, the government as a whole acted as regent. The split among progressives was about more than just legal forms; it was about how much power Espartero would have.

Government Challenges

The division among progressives continued in the Cortes after the February 1841 elections. "Radical" progressives, led by Joaquín María López, and "moderate" progressives, led by Salustiano de Olózaga, had a majority in the Congress of Deputies. To counter this, Espartero filled the Senate with his supporters, using the powers given to the Crown by the Constitution of 1837. He also surrounded himself with military men loyal to him, which made some people fear he was creating a military dictatorship.

Espartero's Regency faced opposition from moderates, led by O'Donnell and Narváez. Since they couldn't win power through elections, they tried military takeovers. They had help from the former regent, Maria Christina, who was in exile in Paris. These takeovers began in October 1841. Civilian uprisings also occurred in big cities.

These military coups were seen as a way to influence politics. They often had civilian support in specific areas. However, some leaders were executed, like Manuel Montes de Oca.

From July 1842, Espartero became more authoritarian. He dissolved the Cortes when they opposed him. In Barcelona, there was a civilian uprising over cotton trade policies. Free traders and protectionists clashed. The military had to retreat to Montjuïc Castle and bombarded the city on December 3.

Meanwhile, there were internal plots in the Palace about the young queen's education. Espartero appointed new tutors, Argüelles and the Countess of Espoz y Mina. They clashed with people still loyal to the former Regent, like the Marquise of Santa Cruz.

The End of Espartero's Regency

After the bombardment of Barcelona in 1842, opposition to Espartero grew, even from his former allies like Joaquín María López.

After the March 1843 elections, Espartero tried to reconcile with the progressives. He offered to form a government with Olózaga and Cortina, but they refused. He then offered it to Joaquín María López. López proposed a government program that included declaring Isabella II old enough to rule, even though she was only twelve. This would end Espartero's regency.

Joaquín María López's government lasted only ten days. Meanwhile, moderate generals O'Donnell and Narváez, from exile, had gained control of much of the army. In Andalusia, moderates and liberals conspired against the regime. Narváez led an uprising on June 11. By July 22, Espartero had lost power as the uprising spread. Espartero fled to Cadiz and sailed to London.

Isabella II Becomes Queen and the Moderate Decade Begins

Espartero's exile created a power vacuum. Joaquín María López was reinstated as head of government on July 23. To get rid of the "esparterists" in the Senate, he dissolved it and called new elections. He also appointed the City Council and Provincial Council of Madrid, even though this violated the Constitution of 1837. López said it was necessary to save the system.

In September 1843, elections for the Cortes were held. Progressives and moderates formed a coalition, but moderates won more seats. Progressives were still divided. The Cortes decided that Isabella II would be proclaimed old enough to rule as soon as she turned 13 the next month. On November 10, 1843, she swore in the Constitution. The government of José María López resigned. Salustiano de Olózaga, a progressive leader, was asked to form a new government.

Olózaga faced immediate problems. His candidate for president of the Congress of Deputies lost to the Moderate Party candidate, Pedro José Pidal. Olózaga then asked the queen to dissolve the Cortes and call new elections. This led to the "Olózaga incident," where moderates accused him of forcing the queen to sign the decrees. Olózaga resigned, and the moderate Luis González Bravo became president. He called elections for January 1844.

The moderates won the January 1844 elections. This led to progressive uprisings in several provinces in February and March. Progressive leaders like Cortina were imprisoned. In May, General Narváez became president, starting the Moderate Decade (1844-1854). During these ten years, the Moderate Party held power with the Crown's support, and progressives had no chance to govern.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Minoría de edad de Isabel II para niños

In Spanish: Minoría de edad de Isabel II para niños