Social history of post-war Britain (1945–1979) facts for kids

| 8 May 1945 – 3 May 1979 | |

The Beatles, a band originating from Liverpool who became synonyms with the cultural changes of the 1960s, arrive in New York in 1964.

|

|

| Preceded by | Second World War |

|---|---|

| Followed by | Modern Era |

| Monarch | |

| Leader(s) | |

The United Kingdom won the Second World War, but it came at a high cost. The late 1940s were a time of hardship and economic limits. However, things got better in the 1950s with more money and jobs.

The Labour Party, led by Clement Attlee, won the 1945 election by a lot. They formed their first-ever majority government. Labour ruled until 1951. They gave independence to India in 1947. Most other major colonies also became independent in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The UK worked closely with the United States during the Cold War after 1947. In 1949, they helped create NATO. This was a military group against the spread of Soviet Communism. After much discussion, the UK joined the European Economic Community (EEC) on January 1, 1973. This was a group of European countries working together. People moving to Britain from the British Empire and Commonwealth helped create the multicultural society we see today. At the same time, traditional Christian religions became less popular.

Life got better in the 1950s for many people, including the middle and working classes. London stayed a global center for money and culture. But Britain was no longer a superpower. In foreign policy, the UK supported the Commonwealth and the Atlantic Alliance. At home, both Labour and Conservative parties generally agreed on how to run the country. They supported trade unions, controlled businesses, and took over many old industries. The discovery of North Sea oil helped with money problems. But the 1970s saw slow economic growth, more people out of work, and many strikes. Old industries like coal mining and shipbuilding declined. London and the South East stayed rich, as London became a top financial center in Europe.

There were big changes in education during this time. The age for leaving school was raised. Schools were split into primary and secondary levels. The grammar school system, which sorted students by tests, was eventually removed. The status of women slowly got better. A new youth culture appeared in the 1960s. Famous bands like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones became global stars.

Life in Post-War Britain

The Age of Austerity: 1945-1951

In May 1945, the government changed after the war. This led to a new election. The Labour Party won by a large amount. The new Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, said it was the first time a socialist party had won so much support.

During the war, many people wanted big social changes. They linked the Conservative Party to the poverty of the 1930s. People hoped that socialist planning would make the economy work better. There was a feeling that everyone who helped in the war deserved a reward.

When the war ended, the UK was almost out of money. America suddenly stopped its Lend Lease program, which had provided supplies. The economy did not get back to pre-war levels until the 1950s. Because of continued rationing, these years were called the "Age of Austerity."

Britain was almost bankrupt but still had a large global empire. It had a big air force and an army with conscription. To avoid bankruptcy, the government got a loan from the US in 1945. They also received $3.2 billion from the American Marshall Plan from 1948 to 1952. This plan helped Britain modernize its businesses. Britain strongly supported the Marshall Plan. It also helped create the NATO military group in 1949 against the Soviet Union.

Rationing of food and other goods continued after the war. The government tried to control what people bought. The country faced a very cold winter in 1946–47. Coal and railway systems failed. Factories closed, and many people suffered from the cold.

Food and Goods Rationing

Wartime rationing continued. Bread was rationed for the first time to help feed German civilians. Sweets like chocolates were rationed until 1954. For many poor people, rationing actually meant they ate healthier food than before the war. Housewives often protested against the strict rules. The Conservative Party gained support by criticizing rationing and economic controls. They returned to power in 1951.

People's spirits were lifted by the marriage of Princess Elizabeth in 1947. The 1948 Summer Olympics were also held in London. London began rebuilding, but there was not much money for new buildings.

Building the Welfare State

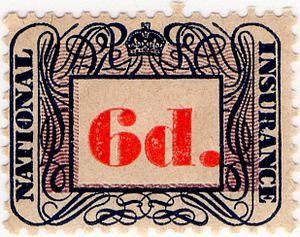

The Labour government's most important actions were expanding the welfare state. This meant creating the National Health Service (NHS). They also took control of industries like coal, gas, electricity, and railways. The welfare state grew with the National Insurance Act 1946. This system built on social security plans from 1911. People who worked had to pay a weekly amount. In return, they got benefits like pensions, health care, and unemployment support.

The National Health Service started in July 1948. It promised free hospital and medical care for everyone, no matter how much money they earned. Labour also built many low-cost council housing for poor families.

The government faced big money problems. Half of the wartime economy had been used for soldiers and weapons. They needed to switch to a peacetime budget while controlling rising prices. New loans from the US and Canada were vital to keep living standards up.

Housing Challenges

There was a huge shortage of homes. Air raids had destroyed half a million houses. Repairs on other homes had been put off. About 750,000 new homes were needed. But there were not enough builders, materials, or money. By 1951, the shortage reached 1.5 million homes. Laws kept rents low but did not lead to more new homes being built. The "New Towns" project did not create enough houses. The Conservative Party made housing a top goal. They oversaw the building of 2.5 million new homes. Most of these were built by local councils.

Industries Under Government Control

The Attlee government took control of major industries and services. They created the "cradle to grave" welfare state. This idea came from economist William Beveridge. The creation of Britain's publicly funded National Health Service was a proud moment for Labour.

Labour did not have detailed plans for taking over industries. They started with the Bank of England, civil aviation, coal, and Cable & Wireless. Then came railways, canals, road haulage, electricity, and gas. Finally, they took over iron and steel. This was different because it was a manufacturing industry. In total, about one-fifth of the economy was taken over by the government.

Taking over these industries mostly went smoothly. But there were two exceptions. Doctors strongly opposed the government taking over hospitals. They reached a compromise that allowed doctors to also have private practices. Most doctors decided to work with the NHS. The takeover of the iron and steel industry was much more debated. Unlike coal, it was profitable and efficient. Owners, businesses, and the Conservative Party were against it. The House of Lords also opposed it. But a law in 1949 reduced their power to delay new laws. Iron and steel were finally taken over in 1951. But Labour lost the election that year. The Conservatives sold iron and steel back to private companies in 1955.

The process for taking over industries was to create public companies. The owners of company shares were given government bonds. The government then fully owned each company. The managers stayed the same but now worked for the government. For the Labour Party, taking over industries was a way to control the economy. It was not meant to modernize old industries or make them more efficient. There was no money for modernization. However, the Marshall Plan did push many British businesses to use modern management methods.

Labour's Challenges

Labour struggled to keep public support. To make people happier, the government ended rationing for potatoes, bread, shoes, clothing, and jam in 1948–49. They also increased petrol for summer drivers. But meat was still rationed and hard to find.

Labour barely won the 1950 election with a small majority. Defence spending became a big issue for Labour. It reached 14% of the country's income in 1951 during the Korean War. These costs put a strain on government money. The finance minister, Hugh Gaitskell, introduced charges for NHS dentures and glasses. This led to two ministers, Aneurin Bevan and Harold Wilson, resigning. This caused problems within the Labour Party for a decade. The Conservatives benefited from this and won more elections.

Historians say that Labour leaders under Attlee worked through normal government channels. They did not feel the need for big protests. This led to a strong expansion of the welfare system, especially the NHS. Taking over private industries focused on older, declining ones like coal mining. Labour promised economic planning but did not set up good ways to do it. Much of the planning was pushed by the Marshall Plan.

Britain and the Cold War

Britain faced big money problems and needed cash for imports. It responded by reducing its involvement in other countries, like Greece. It also shared the difficulties of the "age of austerity." Early worries that the US would stop nationalization or welfare policies were wrong.

Under Attlee, foreign policy was handled by Ernest Bevin. He looked for new ways to bring Western Europe together in a military group. One early attempt was the Dunkirk Treaty with France in 1947. Bevin wanted a Western European security system. He was eager to sign the Treaty of Brussels in 1948. This treaty brought Britain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg together for safety. It led to the creation of NATO in 1949. NATO was mainly to defend against Soviet expansion. It also helped its members work together and modernize their armies.

Bevin started ending the British Empire. India and Pakistan became independent in 1947. Burma (Myanmar) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) followed in 1948. In January 1947, the government decided to develop Britain's nuclear weapons. This was mainly to make Britain safer and keep its status as a world power. A few top officials made this decision in secret. They did not tell the rest of the government. This was to prevent the Labour Party's anti-nuclear members from stopping it.

Churchill Returns to Power

In the late 1940s, the Conservative Party used public anger about food rationing, shortages, and government rules. They used this unhappiness with Labour's socialist policies to get support from the middle class. This helped them win the 1951 election. Their message was especially popular with housewives. They faced harder shopping conditions after the war than during it.

The Labour Party's popularity kept falling. But there were good moments, like the Festival of Britain in summer 1951. This was a national exhibition held across the country. Historian Kenneth O. Morgan called the Festival a "triumphant success." Thousands of people visited the South Bank site in London every day. They enjoyed the Dome of Discovery and the Skylon. People who had faced years of war and hardship showed they could still have fun. The Festival also showed off the creativity of British scientists and engineers.

The Conservative Party gained trust on economic matters. Their Industrial Charter focused on removing unnecessary controls. Winston Churchill was the party leader. He brought in Lord Woolton to modernize the party. Woolton rebuilt local party groups. He focused on getting more members, money, and a clear national message. He emphasized that their opponents were "Socialists" rather than "Labour."

The Conservatives narrowly won the October 1951 election. However, Labour received more votes overall. Most of the new programs started by Labour were kept by the Conservatives. They became part of the "post war consensus" that lasted until the 1970s. The Conservatives ended rationing and reduced controls. They sold the famous Skylon for scrap. They worked with trade unions. They kept industries under government control, but sold back the steel and road haulage industries in 1953.

The Golden Age: Prosperity and Change

In the 1950s, rebuilding continued. People from Commonwealth nations, like the Caribbean and India, began moving to Britain. The shock of the Suez Crisis in 1956 showed that Britain was no longer a superpower. It also realized it could not afford its large Empire anymore. This led to decolonization. Britain withdrew from almost all its colonies by 1970.

Unemployment was much lower during this "Golden Age" than before or after. For example, from 1950 to 1969, only 1.6% of British workers were unemployed. This was much lower than the 13.4% before this period. People also reported being happier. In 1957, 52% said they were "very happy," compared to 36% in 2005.

The 1950s and 1960s saw continued modernization of the economy. The first motorways were built. Britain kept its important financial role in the world. It used the English language to promote its education system globally. With low unemployment, living standards kept rising. New private and council homes were built, and fewer slum properties remained.

During this time, unemployment in Britain was only about 2%. As prosperity returned, Britons focused more on their families. Leisure activities became easier for more people to enjoy. Holiday camps became popular in the 1950s. People also had more money for hobbies. The BBC's early television service got a big boost in 1953. This was for the coronation of Elizabeth II. Twenty million people worldwide watched it on TV. Many middle-class people bought televisions for the event. In 1950, only 1% of homes had TVs. By 1965, 25% did, and many more were rented.

Small local shops were replaced by chain stores and shopping centres. Cars became a big part of British life. This led to traffic jams in cities. It also caused new buildings to spread along major roads. These problems led to the idea of a green belt. This was to protect the countryside from city growth.

The average standard of living rose greatly after the war. Real wages increased by 40% from 1950 to 1965. Workers in lower-paid jobs saw a big improvement in their wages. Spending became more equal. Rich landowners had to pay more taxes. Wages increased, leading to a 20% rise in consumer spending. Economic growth continued at about 3%. The last food rations ended in 1954. As a result, many working-class people could buy consumer goods for the first time. The most popular purchase was a washing machine. Ownership went from 18% in 1955 to 60% in 1966.

Other benefits became more common. In 1955, 96% of manual workers got two weeks of paid holiday. By the late 1950s, Britain was one of the richest countries. By the early 1960s, most Britons enjoyed a level of wealth that only a few had before. Young people had extra money for fun, clothes, and even luxuries. In 1959, Queen magazine said Britain had entered "an age of unparalleled lavish living." Prime Minister Harold Macmillan said that "the luxuries of the rich have become the necessities of the poor."

By 1963, 82% of homes had a television. 72% had a vacuum cleaner, 45% a washing machine, and 30% a refrigerator. The gap in what professional and manual workers owned became much smaller. Household amenities improved steadily. From 1971 to 1983, homes with their own bath or shower rose from 88% to 97%. Those with an indoor toilet rose from 87% to 97%. Also, homes with central heating almost doubled, from 34% to 64%. By 1983, 94% of homes had a refrigerator, 81% a color TV, 80% a washing machine, and 57% a deep freezer.

However, compared to Europe, the UK was falling behind. Between 1950 and 1970, most European Common Market countries had more telephones, refrigerators, TVs, cars, and washing machines per household. Education grew, but not as fast as in rival nations. By the early 1980s, 80% to 90% of school leavers in France and West Germany received job training. In the UK, it was only 40%. By the mid-1980s, over 80% of students in the US and West Germany stayed in education until age eighteen. In Japan, it was over 90%. In the UK, it was barely 33%.

Economic Challenges of the 1970s

Britain's economic prosperity, measured by income per person, steadily dropped. It went from seventh place in 1950 to twelfth in 1965, and to twentieth in 1975. A Labour politician, Richard Crossman, felt a "sense of restriction, yes, even of decline" after visiting Canada. He saw Britain "always teetering on the edge of a crisis."

In the 1970s, the excitement of the 1960s faded. Instead, a series of economic crises hit. Many trade union strikes pushed the British economy further behind other countries. This led to a major political crisis. The "Winter of Discontent" in 1978–79 saw widespread strikes by public workers. This caused great inconvenience and anger among the public.

A positive development was the discovery of large oil deposits in the North Sea. This allowed Britain to become a major oil exporter to Europe. This was important during the 1970s energy crisis.

Northern Ireland and the Troubles

In the 1960s, Terence O'Neill, the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, tried to make changes. He wanted to give a stronger voice to Catholics, who made up 40% of the population. But his plans were stopped by militant Protestants. Growing demands for change from nationalists and strong resistance from unionists led to civil rights protests. Clashes became out of control. The army struggled to contain the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the Ulster Defence Association.

British leaders worried that if they pulled out, it would lead to widespread fighting. This could cause hundreds of thousands of refugees. So, the UK Parliament in London closed Northern Ireland's parliament. It imposed direct rule from London. By the 1990s, the IRA's campaign failed to gain wide support. This led to talks that resulted in the 'Good Friday Agreement' in 1998. This agreement was popular and largely ended the worst violence of The Troubles.

Social and Cultural Changes

Religion in Britain

In the late 1940s, Britain was still a Christian nation. People generally believed in Christianity and respected it. They also linked it to good behavior. However, by the middle of the century, Britain was Christian mostly in a general sense. Belief was more of a leftover idea than a strong conviction. Protestant churches, like Anglican and non-conformist ones, saw fewer people attending. Even the strict Sunday rules in Wales and Scotland faced challenges. People wanted cinemas to open in Wales and golf courses in Scotland on Sundays.

The Changing Role of Women

The Housewife's Role

The 1950s was a tough time for feminism. After World War II, there was a new focus on traditional marriage and the nuclear family. This was seen as the base of the new welfare state. Women were expected to raise children and take care of the home. Their husbands were expected to work outside the home. This led to the popular term 'occupation housewife'. It meant a woman's full-time job was childcare, cooking, cleaning, and shopping.

In 1951, 75% of adult women were married. For women aged 45 to 49, 84.8% were married. Marriage was more popular than ever. A popular book in 1953 said: "A happy marriage may be seen... as the best course, the simplest, and the easiest way of life for us all." The average age for first marriage also fell. By the late 1960s, men and women were marrying at the youngest average age in a century.

After the war, childcare facilities closed. Help for working women became limited. But the new welfare state included family allowances. These were meant to help families. They supported women in their role as wives and mothers. Some historians argue that the vision for a "New Britain" in 1945 had a very traditional view of women.

Popular media, like films, radio, books, and women's magazines, supported traditional marriage. In the 1950s, women's magazines had a lot of influence. They shaped opinions on many topics, including women's jobs. A book from 1950, The Practical Home Handywoman, guided housewives on sewing, cooking, and basic carpentry.

Daytime television also reinforced gender roles. Since men were usually at work, shows were mostly for women. Marguerite Patten, a cooking show host in the 1950s and 60s, became very famous. Her shows gave ideal recipes for women during rationing. They used ingredients that were easy to find.

Education also taught young girls traditional gender roles. More girls went to school beyond primary level. But the government used this to promote a return to the pre-war family home. They put "gendered curricula in secondary modern education." Differences were clear in 'domestic science lessons'. These aimed to teach girls domestic skills they would have learned at home. Classes like cooking, sewing, and family budgeting were common. Many of these classes continued until the late 20th century. They slowly phased out as equal education for all children became the norm.

Changing Attitudes Towards Women's Work

At the same time, women became more interested in careers outside the home. This was seen in housewives' groups. These groups first pushed for policies to protect mothers. But by the end of the century, their goals shifted. They became more aligned with demands from working women. The National Federation of Women's Institutes (WI) took a more traditional stance. They suggested "married women's" shift patterns. These would let women work only during school hours. They would also have more flexible time off if a child was sick. In contrast, the National Council of Women (NCW) supported childcare facilities. They believed these did not harm children's well-being.

In the 1950s, Britain moved towards equal pay. Teachers got equal pay in 1952. Men and women in the civil service got it in 1954. This was thanks to activists like Edith Summerskill.

Feminist writers of this period, like Alva Myrdal and Viola Klein, started to suggest that women could combine home duties with outside jobs. Feminism was strongly linked to social responsibility. It involved the well-being of society as a whole. This often meant sacrificing personal goals for feminists. Even women who called themselves feminists strongly supported the idea that children's needs came first.

"Career novels" were popular books for children and young adults. These novels focused on working women with ambition for their careers. The heroines often married and found love. But these relationships were always shown as equal partnerships. The main character did not have to give up her career.

Equal pay became a topic in the 1959 election. The Labour Party's plan included "the right to equal pay for equal work." Polls in 1968-69 showed public opinion favoring equal pay. Nearly three-quarters of those asked supported it. The Equal Pay Act 1990 was passed by a Labour government with Conservative support. It took effect in 1975. Women's wages for similar work rose sharply. They went from 64% of men's wages in 1970 to 74% by 1980. Then they stopped rising due to high unemployment.

The Rise of Teenagers

The word "teenager" first appeared in Britain in the late 1930s. But national attention focused on them from the 1950s onwards. Better nutrition meant young people were physically more mature than before. They were also better educated. Their parents had more money. National Service, which was compulsory military service for young men aged 17–21, ended in 1960. This gave young men more freedom. Washing machines, vacuum cleaners, and prepared foods meant teenage girls were no longer needed for as many household chores.

Most middle and upper-class teenagers were still in school. So, much of the teenage culture after the war came from the working class. There were two important aspects. First, the economics of teenage spending. Second, a middle-class worry about a decline in British morality. In 1960, there were 5 million unmarried young people aged 15–25. They controlled about 10% of all personal income in Britain. They had good-paying blue-collar jobs after the austerity years. They usually lived at home. They did not spend their money on housing, groceries, or savings. Instead, they focused on keeping up with their friends. New stylish clothes were quickly copied. Weekend dances and music shows were very popular. One estimate in 1959 said teenagers spent 20% of their money on clothes, makeup, and shoes. 17% went to drinks and cigarettes. 15% went to sweets and snacks. The rest, almost half, went to pop entertainment. This included cinemas, dance halls, sports, magazines, and records. Spending money helped them feel like they belonged to a group.

Worries about teenagers appeared during times of big social change. Teenager problems first gained public attention during the war. There was a rise in youth crime. By the 1950s, people worried about American comic books that teenagers liked. These books were censored in 1955. By then, British media showed teenagers as rebellious and impulsive. Subcultures like skinheads and Teddy Boys seemed threatening to older generations. But the worries among politicians and older people were often not true. There was growing cooperation between parents and children. Many working-class parents had new money. They eagerly encouraged their teens to enjoy more adventurous lives.

Starting in the late 1960s, the counterculture movement spread from the United States. The UK did not have the same intense social problems as the US. But British youth easily connected with American youth's desire to challenge older social rules. Music was a powerful force. British groups like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Who, Led Zeppelin, and Pink Floyd became hugely popular. They made young people question everything, from clothing to the class system.

The anti-war movement in Britain was fueled by the counterculture. It worked with American groups. It shifted from focusing on nuclear war with Russia to supporting rebels in Southeast Asia.

Changes in Education

The Education Act 1944 was a response to new social and educational needs after the war. It was prepared by Conservative MP Rab Butler. The Act started in 1947. It created the modern split between primary education and secondary education at age eleven. Before, children often went to the same school from age five until they left in their early teens. The new Labour government adopted the Tripartite System. This had grammar schools, secondary modern schools, and secondary technical schools. They rejected the idea of comprehensive schools, which many in Labour preferred as more equal. In the tripartite system, students who passed an exam could go to a prestigious grammar school. Those who did not pass went to secondary modern or technical schools. The age for leaving school was raised to fifteen. The elite system of public schools stayed mostly the same. The new law was praised by Conservatives because it respected religion and social order. Labour liked it because it gave new chances to the working class. The public liked it because it ended school fees. The Education Act became a lasting part of the Post-war consensus.

While the new law was widely accepted, one part caused debate. Left-wing critics said grammar schools were elitist. This was because students had to pass a test at age eleven to get in. Opponents, mostly in the Conservative Party, argued that grammar schools allowed students to get a good education based on their ability, not their family's money. By 1964, one in ten students were in comprehensive schools. These schools did not sort children at age eleven. Labour education minister Anthony Crosland (from 1965) pushed to speed up this change. When Margaret Thatcher became Minister for Education in 1970, one in three schools were comprehensive. This number doubled by 1974, even though she tried to stop the trend against grammar schools. By 1979, over 90% of schools in the UK were comprehensive.

Growth in Higher Education

Higher education grew a lot. Colleges in cities like Nottingham, Southampton, and Exeter became universities. By 1957, there were 21 universities. Growth was even faster in the 1960s. New universities like Keele, East Anglia, and Sussex were built. This brought the total to 46 in 1970. Some universities became known for specific subjects. For example, Medicine at Edinburgh, engineering at Manchester, and Science at Imperial College London. Oxford and Cambridge remained the most important universities. They attracted top students from across the Commonwealth. But many of their best researchers moved to the United States. There, salaries and research facilities were much better. Into the 1960s, most university students came from middle and upper-class families. The average university had only 2,600 students in 1962.

Media and Entertainment

For the BBC, the main goal after the war was to stop threats from American private broadcasting. It also wanted to continue John Reith's mission of improving culture. The BBC remained powerful, even with the arrival of Independent Television in 1955. Newspaper owners had less political power after 1945. Major newspapers became part of large companies that cared more about profits than politics. Local newspapers almost disappeared. Growing competition came from non-political journalism and other media like the BBC.

Sports and Cinema

Watching sports became very popular after the war. Attendance at games soared. Despite money problems, the government was proud to host the 1948 Olympics. Britain's athletes won only three gold medals, while Americans won 38. Budgets were tight, and no new facilities were built. Athletes received extra food rations, like dock workers and miners. They were housed in existing buildings. Male athletes stayed at RAF and Army camps. Women stayed in London dormitories. Sports competitions were minimal during the war. But by 1948, 40 million people a year watched football matches. 300,000 per week went to motorcycle speedways. Half a million watched greyhound races. Cinemas were full, and dance halls were busy.

Immigration to Britain

After many years of low immigration, new arrivals became important after 1945. In the decades after World War II, most immigrants came from the former British Empire. This included Ireland, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, the Caribbean, South Africa, Kenya, and Hong Kong.

The new immigrants usually joined close-knit communities of their own ethnic group. For example, Irish arrivals became part of working-class Irish Catholic areas. They kept their distinct identity in terms of religion, culture, and Labour politics.

Enoch Powell, a Conservative politician, spoke out against immigration in April 1968. He warned of future violence and problems if immigration from non-White countries continued. His speech caused a lot of controversy. While political leaders criticized Powell, he gained a lot of public support.

Understanding Post-War Britain

The Post-War Consensus Idea

The post-war consensus is a way historians describe political agreement from 1945 to 1979. This was when Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister and changed things. The idea is that there was a wide agreement on policies. These policies were developed in the 1930s, promised during World War II, and put into action under Attlee. The policies included a mixed economy, government spending to manage the economy, and a broad welfare state. Recently, historians have debated if such a consensus truly existed.

Historian Paul Addison developed the idea of the post-war consensus most fully. The main argument is that in the 1930s, Liberal Party thinkers like John Maynard Keynes and William Beveridge created plans. These plans became popular during the war. The wartime government promised a much better Britain after the war. The government during the war, led by Churchill and Attlee, agreed on plans for a better welfare state. These promises included the National Health Service, and more education, housing, and welfare programs. It did not include taking over all industries. That was a Labour Party idea. The Labour Party did not challenge the system of elite public schools. These became part of the consensus, as did comprehensive schools. Labour also did not challenge the importance of Oxford and Cambridge universities. However, the consensus did call for building many new universities to greatly expand education. Conservatives did not challenge the socialized medicine of the National Health Service. In fact, they claimed they could run it better. In foreign policy, the consensus meant an anti-Communist Cold War policy. It also meant ending the empire, close ties to NATO, the United States, and the Commonwealth. Slowly, ties to the European Community also grew.

The model says that from 1945 until Thatcher in 1979, there was a broad agreement among different political parties. This was about social and economic policy. It included the welfare state, national health services, education reform, a mixed economy, government rules, and full employment. Except for taking over some industries, these policies were largely accepted by the three main parties. Industry, finance, and trade unions also agreed. Until the 1980s, historians generally agreed on the consensus. Some historians were disappointed that the consensus was a modest plan. They felt it stopped Britain from becoming a fully socialist society. Other historians complained that the post-war changes were not enough for the sacrifices made during the war. They felt it was a betrayal of people's hopes for a fairer society. In recent years, historians have debated whether this consensus ever truly existed.

The 1960s: A Cultural Revolution?

In his book, The Sixties: Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy and the US, Arthur Marwick argued that the UK's political leaders responded to the youth culture of the 1960s in a unique way. He called it a "measured response." He said this was part of "British exceptionalism." It involved strategies of working with and compromising with young people's growing demands. This was different from other Western countries. There, governments often resisted the rising power of young people more harshly. Marwick argued that by being more flexible, the UK avoided much of the social tension seen in other countries in 1968. For example, lowering the voting age to 18 in 1969 fits with Marwick's idea of the government working with the youth.

Images for kids

-

Clement Attlee was Prime Minister from 1945 to 1951.

-

Demonstration in June 1978, after the killing by racists of Altab Ali, a young Bangladeshi man, in May 1978, against the National Front and other racists who were active in the Brick Lane area

See also

- Social history of post-war Britain (1945–1979) § Notes

- History of gambling in the United Kingdom

- The Spirit of '45, a 2013 documentary film

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |