St Cuthbert's Church, Edinburgh facts for kids

Quick facts for kids St Cuthbert's Church |

|

|---|---|

| The Parish Church of Saint Cuthbert | |

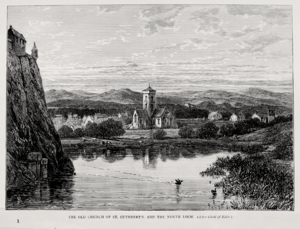

St Cuthbert's seen from Edinburgh Castle

|

|

| 55°56′59″N 3°12′18″W / 55.94965°N 3.20505°W | |

| Location | 5 Lothian Road, Edinburgh, EH1 2EP Scotland |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Denomination | Church of Scotland |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | [1] |

| History | |

| Former name(s) | West Kirk (17th century–19th century) |

| Founded | 7th century |

| Dedication | Cuthbert |

| Dedicated | 16 March 1242 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Category A listed |

| Designated | 14 December 1970 |

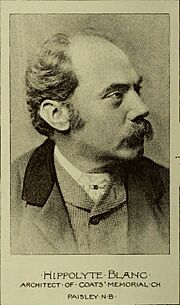

| Architect(s) | Hippolyte Blanc |

| Style | Renaissance, Baroque |

| Years built | 1892–1894 |

| Administration | |

| Presbytery | Edinburgh |

The Parish Church of St Cuthbert is an important church in the heart of Edinburgh, Scotland. It belongs to the Church of Scotland. People believe it was first built way back in the 7th century. For a long time, its parish (the area it served) was huge, covering much of the land around Edinburgh's Old Town. The church building you see today was designed by an architect named Hippolyte Blanc and finished in 1894.

St Cuthbert's sits in a large churchyard, which is like a big garden with graves. This churchyard is next to Princes Street Gardens and Lothian Road. The church was probably started around the time of Saint Cuthbert himself. The first official mention of the church was in 1128. That's when King David I gave it to Holyrood Abbey. Back then, the church served a very large area. Over time, this area got smaller as new churches were built. Many of these new churches started as smaller "chapels of ease" connected to St Cuthbert's.

In 1560, during the Scottish Reformation, St Cuthbert's became a Protestant church. For many years after that, it was often called the West Kirk. Because it's located right at the bottom of Castle Rock, the church was damaged or destroyed at least four times between the 1300s and 1600s.

The church building standing now was built between 1892 and 1894. It replaced an older Georgian-style church. That older church had also replaced an even older building. Hippolyte Blanc designed the current church in the Baroque and Renaissance styles. It still has the tall steeple from the previous church. The Buildings of Scotland guide says the church's inside decorations are "extraordinary."

Inside, you can find amazing stained glass windows by famous artists like Louis Comfort Tiffany and Douglas Strachan. There are also beautiful paintings by Gerald Moira and John Duncan. You'll also see memorials by John Flaxman and George Frampton. The church even has a set of ten bells that can be rung in a special way called change ringing. Since 1970, the church has been a "Category A listed building." This means it's a very important historic building.

Many of St Cuthbert's ministers have been important leaders in the Church of Scotland. One of them, Robert Pont, was the head of the General Assembly six times in the late 1500s. Today, the church helps homeless people and works with businesses in Edinburgh.

Contents

A Look at St Cuthbert's History

From Early Days to the Reformation

No one knows exactly when the first St Cuthbert's church was built. Some historians think it was in the late 600s, around the time of Saint Cuthbert. Others believe it was founded later, after Queen Margaret arrived in Scotland in 1069. It might even be the church mentioned in 854 as belonging to Lindisfarne. The church's parish might have covered all of Edinburgh before St Giles' Church was built in the 1100s.

The oldest clear record of the church is from around 1127. King David I gave St Cuthbert's Church, near the castle, a piece of land. This land was "all the land below the castle, from the spring... along the road to the church."

Soon after, in 1128, King David I gave St Cuthbert's parish to Holyrood Abbey. This gift also included two smaller chapels in Liberton and Corstorphine. These chapels later became independent churches around the mid-1200s. The church of St Cuthbert was officially blessed by the bishop of St Andrews on March 16, 1242. This was probably a re-blessing because old records might have been lost.

By the 1400s, the church had several smaller altars, each with its own chaplain.

In 1773, something interesting was found when the old church was being taken down. Workers discovered bones and a lead container inside a lead coffin. The container had a sweet smell, and inside it was an embalmed human heart. This heart might have belonged to a crusader whose family brought it back from the Holy Land.

The church might have been destroyed during attacks on Edinburgh in 1385 and 1544. After the 1544 attack, it might have been rebuilt. In 1550, someone named Alexander Ales mentioned "the new Parish Church of St Cuthbert's." By the time of the Scottish Reformation, St Cuthbert's parish was very large. It surrounded the towns of Edinburgh and Canongate. It stretched from Newhaven in the north to Colinton in the south.

The first Protestant minister of St Cuthbert's was William Harlaw, a friend of John Knox. In 1574, Robert Pont joined Harlaw. Pont was good at both law and religion. He became the leader of the General Assembly six times. John Napier, who invented logarithms, was also an elder (a church leader) at St Cuthbert's around 1600.

Times of Conflict: 1572–1689

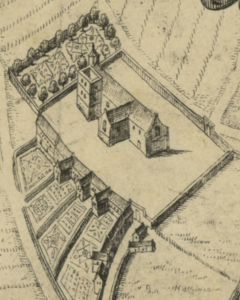

In the 1500s and 1600s, St Cuthbert's was often in danger because it was so close to Edinburgh Castle. In 1573, during a siege of the Castle, soldiers set fire to the church. It was likely rebuilt after this. In 1593, a new, smaller church called the "Little Kirk" was built at the western end.

When King Charles I created the Diocese of Edinburgh in 1633, St Cuthbert's became part of it. The church was damaged again during the Bishops' Wars from 1640 to 1642. The church was also used by Oliver Cromwell's soldiers in 1650. The church members had to meet in the Town's College until 1655.

In 1660, when bishops were brought back to the Church of Scotland, the ministers and most of the church members supported the Covenanters. They were forced out of the official church. David Williamson and James Reid led the church members at a new location in the Dean.

In 1689, during the Glorious Revolution, the church was damaged by cannons from the Castle. The church members moved to the Dean again. When William of Orange became king, bishops were removed from the Church of Scotland. The Crown (the king or queen) then had the right to choose St Cuthbert's ministers. However, this could cause problems. In 1732, when Patrick Wotherspoon was chosen as minister, it caused a riot outside the church. David Williamson returned as minister and was a very important person in the church and government.

From the 1700s to Today

St Cuthbert's supported the Hanoverian kings during the Jacobite uprisings. It even sent volunteers to help stop the 1715 rebellion. During the 1745 rebellion, Jacobite soldiers stayed in St Cuthbert's. Even though the Jacobites stopped worship in other city churches, services continued as usual at St Cuthbert's. The minister, Neil McVicar, famously prayed for the king he meant, not for Charles Edward Stuart.

St Cuthbert's was also involved in the early days of Methodism. In 1764, John Wesley, a founder of Methodism, visited St Cuthbert's for communion.

By the mid-1700s, the church building was falling apart. In 1745, the roof of the Little Kirk was destroyed. In 1772, some seats collapsed, and the building was declared unsafe. The church members met in a Methodist Chapel for a while. A new church building opened on July 31, 1775.

The Disruption of 1843 didn't affect St Cuthbert's much. Neither of its ministers left to join the new Free Church. However, six elders did leave and started Free St Cuthbert's.

By the late 1800s, the 1700s church was too small for the growing number of members. The last service in the old church was on May 11, 1890. The first stone for the new church was laid on May 18, 1892. Queen Victoria even sent a message. The new church, designed by Hippolyte Blanc, opened on July 11, 1894. More decorations and art were added inside the church throughout the 1900s. On September 11, 1930, the famous writer Agatha Christie got married in the church's memorial chapel.

The Church Building: Inside and Out

Outside the Church

The current church, except for its steeple, was designed by Hippolyte Blanc. It was built between 1892 and 1894 in the Renaissance and Baroque styles. The outside of the church is made of cream-colored sandstone. It has smooth stone decorations at the corners. The roof is gently sloped and covered with slate tiles.

The north and south sides of the church look almost the same. They have tall, rounded windows on the upper level. The lower level has rectangular windows. The very end section on each side sticks out a little and has a door. Along the top of these sections is a tall stone wall.

Towards the east, on each side, there's a shallow section with a triangular top. This is called a transept. It has a door with columns and small windows. Above that, there are three rounded windows. On the north side, steps go down to a rounded doorway in the basement. This is the Nisbet of Dean family burial vault, built in 1692. It was kept when the new church was built.

The two towers at the east end of the church are in the Baroque style. They have small rectangular windows on the upper floors and doors on the ground floor. Each tower has decorative urns at the corners and a lantern on top. The lantern has a square base with open arches and an octagonal (eight-sided) top with round windows. Each top has a dome with a ball on it.

The two towers frame the east side of the church. The middle part is a semi-circular section called an apse. It has a leaded half-dome roof. The lower part of the apse is plain, but the upper part has three sections with columns. Each section has a rectangular window and carved decorations.

The Steeple

The very bottom part of the tower on the west side is from the 1775 church. It has a large sculpture from 1844 by Alexander Handyside Ritchie. This sculpture shows David Dickson blessing children. Above it is a window with a blocked-out middle section. The tower ends with a simple triangular top, and a sundial from 1774 is below it. A small chapel for war memorials sticks out from the north side of the tower's ground floor.

Above this first part, the steeple designed by Alexander Stevens begins. It's narrower than the tower below. The steeple has several levels, separated by horizontal bands. The first level has a round window on the west side. The second level rises above the roof line and has a rounded, latticed window on each side. The third level has four clock faces from 1789. Urns sit on top of the corners of the second and third levels.

Above the third level is an octagonal (eight-sided) bell tower. It has rounded openings for the bells and columns. The bell tower has an eight-sided spire with circular openings. A weather vane sits on top.

Inside the Church

The main part of the church, called the nave, is wide and has a flat ceiling with sections. A U-shaped balcony, supported by marble columns, runs along the north, south, and west walls. Rounded arches open into the transepts and the chancel (the area near the altar). The west balcony was made shorter between 1989 and 1990. This was done to create new rooms and make the church easier to access for people with disabilities. The ground floor became the Lammermuir Room, with the Lindisfarne Room above it. The upper floor of the south transept became the Nor' Loch Room.

The chancel has a semi-circular apse. Three sections, separated by columns, end in rounded arches that fit into the curved ceiling. Each section has a window. Between the nave and the apse, there's one section with rounded arches and a curved ceiling. The chancel steps are made of marble with mosaic floors. In 1928, the chancel was decorated with orange marble columns.

Peter MacGregor Chalmers redesigned the ground floor of the tower as a memorial chapel for the First World War. It opened in 1921. The chapel has a shallow, curved ceiling with sections. The lower walls are covered with marble slabs that have the names of the parish members who died in the war. The floor is also marble. In the middle of the north wall, a rounded arch leads to a simple apse. This apse is covered in gold mosaic tiles and has a small window. The south wall has a rounded window. Above the chapel are the session room and the choir room.

How People See the Church

While many liked the old Georgian steeple, people had mixed feelings about Blanc's new design. As the church was being built, there were debates about the eastern towers. A newspaper called The Scotsman criticized the new church's look. However, the Edinburgh Evening Dispatch said the church created a "worshipful feeling."

Later, some people felt the fancy Baroque decorations didn't fit a Presbyterian church. Others described the church as "handsome and ornate." The Buildings of Scotland guide praises Blanc's interior but says the outside looks like "an uneasy compromise." They do, however, love the east side, saying it "succeeds by sheer swank."

The church has been a "Category A listed building" since 1970.

Special Features Inside

St Cuthbert's is known for its beautiful decorations and furnishings. Many of these are inspired by the Italian Renaissance. In the years after the church opened in 1894, these features caused some debate. Some people loved their beauty, while others thought they were too fancy for a Presbyterian church. New features were added throughout the 1900s.

Chancel Furnishings

The main focus at the east end of St Cuthbert's is the communion table. It was ready when the church opened in 1894. The table is made of white marble. Its front has three sections with columns. The middle section has a cross made of Aventurine marble with a gold center. This cross looks like the one found in Saint Cuthbert's tomb. The other sections are decorated with mother of pearl and lapis lazuli.

On the north side of the chancel arch is the marble pulpit. Designed by Hippolyte Blanc, it was put in place in 1898. The pulpit stands on four red marble pillars with white tops. The main part of the pulpit is covered with green marble. Its middle section has a carved angel. Under the pulpit, the church's foundation stone rests on pieces of old Gothic stone found when the previous church was taken down.

Next to the font is the lectern, which is a stand for reading. It's a full-length bronze angel, sculpted by David Watson Stevenson and installed in 1895.

On the south side of the chancel arch is the font, designed by Thomas Armstrong and installed in 1908. The font is six-sided and made of white marble. It has a bronze portrait by MacGill. The bowl has a bronze sculpture of a mother and child, based on Michelangelo's Madonna of Bruges. When it was installed, this sculpture caused arguments. Some loved its beauty, while others thought a Madonna was not right for a Presbyterian church. The issue was even discussed at the General Assembly in 1912.

Blanc also designed the wooden chancel stalls. The choir stalls have scroll-topped ends, like the pews in the main part of the church. The elders' stalls in the apse have more detailed Renaissance designs.

Artwork

Above the wooden panels, the walls of the apse have an alabaster frieze (a decorative band) showing the Last Supper. This frieze, installed in 1908, is divided into three sections. Its design was adapted by Hippolyte Blanc from Leonardo's famous Last Supper. It was carved by Bridgeman of Lichfield.

In the sections of the chancel ceiling, paintings by Gerald Moira show the Four Evangelists. The curved ceiling of the apse has a scene of Christ in Majesty painted by Robert Hope. The spaces above the chancel arch are decorated with angels painted by John Duncan in 1931. Moira also painted a large mural of Saint Cuthbert on Lindisfarne on the west wall of the nave. When the west end was shortened in 1990, this mural became part of the Lindisfarne Room.

After the south transept gallery was walled off in 1990, a decorative screen was added to the new wall. This screen was designed by students from Edinburgh College of Art.

Memorials

In the entrance area and stairwells, you'll find several memorials. These include a panel for the children of Francis Redfern, with a carving of Christ blessing children by John Flaxman (1802). There's also a tablet for John Napier (1842). You can see memorials to Rocheid of Inverleith (1737) and Watson of Muirhouse (1774). There are also two stone coffins on lion's feet by Wallace and Whyte, remembering Henry Moncreiff-Wellwood and William Paul (1841). A stone marker from the grave of Robert Pont (1608) is also displayed.

To the left of the chancel arch is a bust (a sculpture of the head and shoulders) of John Paul (died 1872) by William Brodie. To the right is the Art Nouveau McLaren Memorial with a carved portrait by George Frampton (1907). Under the north gallery, there's a Renaissance tablet for Alexander Ballantine by Arthur Forman Balfour Paul. At the western entrance to the nave, you'll find the Second World War memorial by Ian Gordon Lindsay (1950). This memorial has wooden screens listing the names of 50 church members who died in the war.

Stained Glass Windows

In 1893, the church leaders decided to add stained glass windows. They wanted a "general and harmonious scheme of scriptural subjects" for the whole church. Almost all of these windows were installed between 1893 and 1912 by Ballantyne & Gardiner from Edinburgh. They show scenes from the Bible within early Renaissance frames. The windows on the north side show scenes from the Old Testament, while those on the south side show scenes from the New Testament. The windows in the apse show the Crucifixion, the Last Supper, and the Nativity.

In the north transept, windows show Ninian, Columba, and Aidan. The windows in the south transept show scenes from the life of Cuthbert. Other windows include one by the Tiffany Glass Company (after 1900) showing David going to meet Goliath. In the war memorial chapel, there's a window by Douglas Strachan (1922) showing the Crucifixion and Cuthbert.

Pipe Organ

The organ at St Cuthbert's was given to the church in 1899 by Robert Cox. It was built by Robert Hope-Jones of Birkenhead. The organ pipes were first placed on either side of the chancel in cases designed by Hippolyte Blanc. The organ was rebuilt and made bigger in 1928. Between 1956 and 1957, it was worked on again and expanded with an extra case in the north transept. The organ was rebuilt again between 1997 and 1998. More changes were made in 2002. The current organ has four keyboards and 67 "speaking stops" (different sounds).

Bells and Silverware

The church tower has a set of ten bells that can be rung in a special way called change ringing. The first eight bells were made in 1902, and two more were added in 1970. In addition, chimes play the Westminster quarters (the tune played by Big Ben). An old bell from 1791 is displayed in the entrance area.

The bells were first rung by young men from the church. During the First World War, women took their place. On June 28, 1919, the bells rang along with a 101-gun salute from Edinburgh Castle. This was to celebrate the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. The sound of the bells was even broadcast on November 15, 1942. They rang to mark the victory in the Second Battle of El Alamein. This was the first time the bells had rung since World War II started in 1939.

The church also owns eight modern silver plates and 25 cups of different ages. The oldest cups are from 1619. There are four silver jugs from 1702 and two from 1881. Two silver bowls for baptisms were bought in 1701. Two collection plates are from 1618, and two more were added during the First World War.

Church Life and Leaders

Ministers of St Cuthbert's

Peter Sutton has been the minister of St Cuthbert's since June 1, 2017. Before becoming a minister, Sutton served in the Black Watch (a military regiment). He also worked in education, serving as a chaplain and headmaster at different schools. The assistant minister is Charles Robertson, who used to be the minister of the Canongate Kirk.

In 1251, the bishop of St Andrews gave the leadership of St Cuthbert's to Holyrood Abbey. After that, it was usually led by one of Holyrood's canons (priests). By the 1400s, chaplains served the church's many smaller altars.

After the Scottish Reformation in 1560, William Harlaw became the first Protestant minister of St Cuthbert's. In 1574, Robert Pont joined him. Pont was also a judge.

Robert Pont's appointment meant the church had two ministers. From 1574, the senior minister was paid £100 a year, and the junior minister received less. When David Williamson died in 1706, the salaries became equal. From 1690 to 1874, the British Crown (the king or queen) had the right to choose the ministers.

William Harlaw and Robert Pont were part of the Church of Scotland's first General Assembly in 1560. Pont was the leader of the General Assembly six times. Later ministers who also led the General Assembly include David Williamson (1702), John Paul (1847), James MacGregor (1891), Norman Maclean (1927), William White Anderson (1951), and Robert Leonard Small (1966).

Ministers of the Senior Charge

- 1560–1578 William Harlaw

- 1578–1602 Robert Pont

- 1603–1625 Richard Dickson

- 1626–1649 William Arthur

- 1649–1664 James Reid

- 1665–1680 William Gordon

- 1680–1689 Patrick Hepburn

- 1689–1706 David Williamson

- 1706–1726 Thomas Paterson

- 1726–1730 George Wishart

- 1732 Patrick Wedderspoon

- 1734–1735 James Dawson

- 1735–1751 Thomas Pitcairn

- 1752–1761 John Hyndman

- 1762–1775 Alexander Stuart

- 1775–1827 Henry Moncreiff-Wellwood

- 1828–1873 John Paul

- 1873–1910 James MacGregor

- 1910–1914 George Gordon Dundas Stewart Duncan

- 1914–1925 Robert Howie Fisher

- 1926–1930 George Fielden Macleod

- 1931–1956 William White Anderson

Ministers of the Collegiate Charge

- 1574–1578 Robert Pont

- 1581–1586 Nicol Dalgleish

- 1586–1606 William Aird

- 1607–1626 William Arthur

- 1630–1649 James Reid

- 1653–1661 Peter Blair

- 1661–1665 David Williamson

- 1666–1675 William Keith

- 1677–1681 Charles Kay

- 1682–1686 Alexander Sutherland

- 1687–1689 David Guild

- 1691–1699 John Anderson

- 1699–1706 Thomas Paterson

- 1707–1747 Neil McVicar

- 1747–1752 George Kay

- 1753–1764 James Mackie Moderator in 1751

- 1765–1785 John Gibson

- 1786–1802 William Paul

- 1803–1842 David Dickson

- 1843–1877 James Veitch

- 1878–1883 James Barclay

- 1884–1910 Andrew Wallace Williamson

- 1911–1914 William Lyall Wilson

- 1915–1937 Norman Maclean

- 1938–1955 Adam Wilson Burnett

Sole Charge

- 1956–1975 Robert Leonard Small

- 1976–2007 Thomas Cuthbertson Cuthell

- 2008–2016 David Denniston

- 2017–present Peter Sutton

Services and Music

St Cuthbert's has three services every Sunday. There's a Communion service at 9:30 a.m. The main morning service is at 11 a.m., with Communion on the second and last Sundays of the month. A formal Communion service also happens every three months. There's an evening service at 6 p.m., with Communion on the first Sunday of the month. Communion is also held at noon on the second Tuesday of each month.

The 11 a.m. Sunday service features the St Cuthbert's Choir. This choir includes volunteers from the church and students who study singing. The Director of Music is Graham Maclagan.

Church Mission and Community Work

St Cuthbert's works with a charity called Steps to Hope. They provide a free meal for up to 100 homeless people every Sunday in St Cuthbert's Hall. They also offer a night shelter for 12 people afterward.

St Cuthbert's also runs OASIS, a program for Edinburgh's business community. OASIS works with other charities to support people in their workplaces. As part of this, the church hosts "Soul Space," which are short reflection sessions. They also offer "Space for Lunchtime Prayers" every Thursday at 1 p.m.

St Cuthbert's is part of Edinburgh City Centre Churches Together. This is a group of churches that work together on charity and community projects.

The church is also a performance venue during the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. You can visit the church from April to September, Tuesday to Friday, from 10 a.m. to 3:30 p.m., and on Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m.

The Friends of St Cuthbert's group has supported the church's work and mission since 2002.

The Churchyard

The churchyard is the large area around the church where people are buried. The very first burial ground was a small mound to the south-west. It was later called the "Bairns' Knowe" (children's hill) because many children were buried there. Records show that this area was open to the countryside until 1597. Sheep and horses used to graze there until a wall was built around the churchyard.

In 1701, more land was added to the west and north-west. This happened when the church was being fixed up, as it had been quite run-down.

In 1787, a marshy area north of the church was drained. This created more space for burials. A bit later, the ground to the south-east was raised and enclosed by a new wall.

In 1827, a watchtower was built to the south-west. This was to protect against grave robbing, which was a big problem back then.

In 1831, the minister's house (manse) to the south was taken down. A new manse and garden were built further south.

In 1841, a railway tunnel was built under a new southern part of the graveyard. This tunnel was for trains going to the new Waverley Station. Many graves had to be moved, and some stones from that time were lost.

In 1863, the entire churchyard was ordered to close because it was "completely full." However, the church refused to stop burials because it was an important source of money. In 1873, the church was taken to court for causing a "nuisance" (a public problem) that was "injurious to health." Even then, it didn't close. In 1874, the council ordered the church to close, but it only did so after a year of appeals.

The churchyard is very impressive. It has hundreds of interesting monuments. These include one for John Grant of Kilgraston and a large Gothic-style tomb for the Gordons of Cluny, designed by David Bryce.

An unusual feature is on the west side of the churchyard. In 1930, Lothian Road was made wider over the churchyard. Because the road was higher, it was built on pillars. The graves remained underneath the road surface. So, the eastern sidewalk of the road actually goes over these graves.

Famous People Buried Here

1600s and 1700s Burials

- Henrie Nisbet of Dean (died 1609), a leader of Edinburgh, buried under the church.

- John Napier (1550–1617), who invented logarithms. He is buried in an underground vault on the north side of the church.

- Rev David Williamson (1636–1706), known as "Dainty Davie." He was a Covenanter and later became a leader of the General Assembly.

- Sir James Rocheid of Inverleith (1715–1787), buried inside the church.

- Alexander Gordon, Lord Rockville (1739–1792).

- Alexander Murray, Lord Henderland (1736–1795), a judge, and his son John Murray, Lord Murray (1778–1858). They have a huge monument north of the church.

- James Erskine, Lord Alva (1722–1796).

- The 15th Earl of Glencairn (1749–1796).

- Cosmo Gordon of Cluny (1736–1800), a politician and co-founder of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

- Rev James MacKnight (1721–1800), a religious writer and leader of the General Assembly.

- Professor James Robertson (1714-1795).

1800s Burials

- Alexander Hamilton (Scottish physician) (1739–1802) and his son James Hamilton (Scottish physician) (1767–1839), both professors at Edinburgh University.

- Rev William Paul (1754–1802), a chaplain to King George III.

- Thomson Bonar (1739–1814), who helped start the Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Richard Crichton (1771–1817), an architect.

- Adam Rolland of Gask (1734–1819), a judge.

- Thomas Morison (1761–1820), a builder and founder of Morrison's Academy.

- George Winton (1759-1822), a builder (his monument is the largest in the churchyard).

- Sir Henry Raeburn (1756–1823), a famous artist.

- David Steuart (1747-1828), a former Lord Provost of Edinburgh.

- Rear Admiral James Haldane Tait (1771–1845).

- Robert Archibald Smith (1780–1829), a composer.

- Thomas Allan (1777–1833), who studied minerals.

- George Watson (1767–1837), an artist, and his son William Smellie Watson (1796–1874), also an artist.

- Mrs Anne Grant (1755–1838), a poet and author.

- Alexander Nasmyth (1758–1840), a famous artist, architect, and inventor. He painted a well-known portrait of Robert Burns.

- John Abercrombie (physician) (1780–1844), a physician.

- Rev David Dickson (1780–1842).

- George Meikle Kemp (1795–1844), who designed the Scott Monument.

- Andrew Combe (1797–1847), who studied the shape of the skull.

- Susan Ferrier (1782–1854), an author.

- Thomas De Quincey (1785–1859), a writer who influenced Edgar Allan Poe.

- William Home Lizars (1788–1859), an engraver.

- James Pillans (1778–1864), an educator.

- James Frederick Ferrier (1808–1864), an important philosopher.

- William Borthwick Johnstone (1804–1865), the first Keeper of the National Gallery of Scotland.

- John Marshall, Lord Curriehill (1794–1868), a law lord.

- Elizabeth C. Clephane (1830–1869), who wrote hymns.

- William Penney, Lord Kinloch (1801–1872), a law lord.

- James Craufurd, Lord Ardmillan (1804–1876), a law lord.

- David Rhind (1808–1883), an architect.

- Duncan McLaren (1800–1886), a Member of Parliament and Lord Provost.

- Priscilla Bright McLaren (1815-1906), a suffragist (someone who fought for women's right to vote) and abolitionist (someone who fought to end slavery).

1900s Burials

- Jane Clapperton (died 1914), a suffragette and novelist.

- Sir Donald Crawford (1837–1919).

- Walter Biggar Blaikie (1847–1928), an engineer, historian, and astronomer.

- Mabel Dawson (1887–1965), an artist.

- Sarah Mair (died 1941), a suffragette.

Images for kids

See also

- Church of Scotland

- Cuthbert

- Hippolyte Blanc

- List of Church of Scotland parishes