Wager Mutiny facts for kids

The Wager Mutiny happened in 1741. It was a famous event after a British warship, HMS Wager, crashed on a lonely island. This island was off the coast of what is now Chile.

The Wager was part of a group of navy ships. They were going to attack Spanish areas in the Pacific Ocean. The Wager got separated from the other ships while sailing around Cape Horn. It crashed during a big storm on an island now called Wager Island. Most of the crew decided to go against their captain, David Cheap. They left him and a few loyal crew members on the island. Then, they sailed away in a changed boat called Speedwell. They planned to go through the Strait of Magellan to Rio de Janeiro, which was controlled by Portugal. Many of the crew who left either died or were left behind during the trip. But the ones who survived eventually made it back to England.

A few days later, a small group from Speedwell went back to Wager Island. They used a smaller boat to get some sails that were left behind. Two young officers, Alexander Campbell and John Byron, managed to join this group. They thought Captain Cheap would be coming with them on Speedwell. When the small boat did not return, Speedwell went back to look for it. But by then, everyone on the island had left. They were trying to sail north to find the main group of ships.

Captain Cheap's group could not handle the journey north. So, they returned to Wager Island three months after they had left. They had given up hope of escaping. However, a few days later, some native Chonos visited the island. After talking, they agreed to guide the group north. They would go to a Spanish area called the Chiloé Archipelago. In return, the Chonos would get the small boat and some guns. Most of Cheap's group died on the journey from hunger and cold. But Cheap and a few others survived. They returned to England in 1745. This was two years after the crew who had left on Speedwell returned. The adventures of the Wager crew became very famous. They inspired many stories written by survivors and others.

Contents

- The Wager Ship and Its Journey

- The Shipwreck and Life on Wager Island

- After the Crew's Disagreement

- The Speedwell's Journey

- Captain Cheap's Group

- The Speedwell Survivors Return to England

- Captain Cheap's Group Survivors Return to England

- Abandoned Speedwell Survivors Return to England

- Campbell's Land Journey to Buenos Aires

- Campbell and the Freshwater Bay Survivors Return to England

- Naval Hearing About the Wager's Loss

- What Happened Next

- See also

The Wager Ship and Its Journey

About HMS Wager

HMS Wager was a British Royal Navy warship. It had 28 guns and was built around 1734. Before the navy bought it in 1739, it was a merchant ship. It made two trips to India for the East India Company. As a merchant ship, it had 30 guns and a crew of 98.

The British Navy bought the Wager in November 1739. It was made ready for naval service between November 1739 and May 1740. The ship was meant to join a group of ships led by Commodore George Anson. This group was going to attack Spanish areas in South America. The Wager's job was to carry extra weapons and supplies for attacks on land.

Commodore Anson's Fleet

Anson's fleet had about 1,980 men, including soldiers. Only 188 of them would survive the entire trip. The fleet included six warships and two supply ships, besides the Wager:

- Centurion, the main ship (60 guns, 400 men)

- Gloucester (50 guns, 300 men)

- Severn (50 guns, 300 men)

- Pearl (40 guns, 250 men)

- Wager (24 guns, 120 men)

- Tryal (8 guns, 70 men)

The two merchant ships were Anna and Industry. They carried extra supplies. The fleet also had 470 sick and injured soldiers. Many of these men were the first to die during the hard journey.

From England to Staten Island

The fleet took 40 days to reach Funchal. There, they got more water, wood, and food. Then they crossed the Atlantic Ocean to Santa Catarina. Two weeks into this journey, the supply ship Industry signaled to Anson. Its captain said his job was done and the ship needed to go back to England. Its supplies were shared among the other ships. A lot of rum was sent to the Wager. The Wager now carried rum, large guns for attacking Spanish forts, and goods for trading with local people.

Many men in the fleet got very sick with scurvy. This was because they did not have fresh fruits or meat. Because so many men were sick, Anson's fleet was not in good shape. They were facing the very difficult trip around Cape Horn.

Anson moved Captain Dandy Kidd from the Wager to the Pearl. He moved Captain Murray to the Wager. Captain Kidd died after the fleet left Santa Catarina. Anson then moved Captain Murray from the Wager to the Pearl. He promoted Lieutenant David Cheap from a small ship called Tryal to captain of the Wager. This was the first time Cheap commanded a large ship. His crew was sick and unhappy. Cheap often got angry and did not respect many of his officers. However, Cheap was a skilled sailor and navigator. He was a strong and loyal officer. Anson told Cheap how important the Wager was. Its weapons and ammunition were needed for attacking Spanish bases in Chile.

Sailing Around Cape Horn

The journey's delays were felt most strongly when the fleet sailed around Cape Horn. The weather was terrible. There were huge waves and strong winds, making it very slow to move west. Also, the Wager's crew was getting sicker. Because of scurvy, few healthy sailors were left to work the ship. They could not even do small repairs to the constantly damaged ropes and sails.

After many weeks of sailing west to get past Cape Horn, the fleet turned north. They thought they had gone far enough west. It was easy to know how far north or south they were. But it was much harder to know how far east or west. This needed accurate clocks or a clear view of the stars. Neither was available in the storm. They guessed their east-west position. This was impossible in the storms and strong currents. Anson wanted to turn north only when he was sure they had passed Cape Horn.

This almost led to a disaster. In the middle of the night, the moon shone through the clouds for a few minutes. It showed the crew on the Anna huge waves crashing onto the coast of Patagonia. The Anna fired guns and showed lights to warn the other ships. Without this warning, Anson's whole fleet would have crashed. All the men would likely have died. The ships turned around and headed south again into huge seas and bad winds. During one very bad night, the Wager got separated from the rest of the fleet. They would never see them again.

The Shipwreck and Life on Wager Island

The Wager Crashes

The Wager, now alone, kept sailing west. The crew argued about when to turn north. If they turned too early, the ship would likely hit land. But more crew members were getting scurvy every day. There were not enough sailors to handle the ship. Captain Cheap wanted to go to Socorro Island. The ship's gunner, John Bulkley, strongly disagreed. He wanted to go to Juan Fernandez, which was further from the mainland. It was less likely to cause the ship to crash. Bulkley was seen as the most skilled sailor.

Bulkley tried many times to convince Cheap to change his mind. He argued that the ship was in bad shape. The crew could not properly sail it to avoid hitting land. This made Cheap's plan to go to Socorro too risky. Also, the area was not well mapped. Bulkley turned out to be right. But Cheap refused to change course. Bulkley did not know that Cheap was following secret orders. The large guns in the Wager's cargo were needed to attack Valdivia.

On May 13, 1741, at 9 AM, the carpenter, John Cummins, thought he saw land to the west. The lieutenant, Baynes, was also on deck but saw nothing. So, the sighting was not reported. Later, Baynes was criticized for not telling the captain. Unknown to the crew, the Wager had sailed into a large, unmapped bay. This bay is now called the Gulf of Penas. The land to the west is now called the Tres Montes Peninsula.

At 2 PM, land was clearly seen to the west and northwest. Everyone was called to sail the ship southwest. During the hurried work, Cheap fell and hurt his shoulder. He had to stay below deck. A terrible storm followed that night. The Wager was damaged and worn out. This made it very hard to get the ship out of the bay. At 4:30 AM, the ship hit rocks many times. Its steering part broke. Even though it was still floating, water flooded parts of the ship. The sick men below deck who could not move drowned. Bulkley and another sailor, John Jones, tried to steer the ship using only the sails towards land. But later that morning, the ship hit again, this time getting stuck.

Shipwrecked on Wager Island

The Wager crashed on the coast of a small, empty island, which became known as Wager Island. Their situation was very bad. They were shipwrecked far south at the start of winter. They had little food on a lonely island with no resources. The crew was dangerously divided. Many blamed Captain Cheap for their trouble. On May 15, the ship's bottom broke open in the middle. Many drunken crew members drowned. The only crew left on board were the boatswain John King, who was a difficult person, and a few of his followers.

The Crew's Disagreement

The crew of the Wager were scared and angry with Cheap. Disagreement and disobedience grew. King fired a cannon from the Wager at the captain's hut. He wanted someone to pick him and his friends up from the wreck.

The crew knew they could face serious punishment if they went against the captain. So, they tried to create a story to explain their actions. A full mutiny probably would not have happened if Cheap had agreed to a plan by Bulkley. Bulkley was trusted by most of the men. He suggested that Cummins, the carpenter, could make the longboat longer. They would turn it into a schooner to hold more men. They would then sail home through the Strait of Magellan to Brazil or the British West Indies, and then to England. Smaller boats would go with the schooner. They would be used to find food along the way. Bulkley's plan had a good chance of working. But Cheap would not agree to it, even after much discussion. He wanted to head north and try to find Anson's fleet.

Cheap was in a difficult spot. Being shipwrecked meant he would automatically face a naval hearing. He could lose his job in the navy and become poor. Or, he could be found guilty of not being brave and be executed. Cheap wanted to sail north along the coast to meet Anson at Valdivia. His officers had warned him that some of his actions would look bad when the navy investigated the loss of the Wager.

The crew who went against Cheap later said his actions justified theirs. This included Cheap shooting a young officer named Cozens. Cheap heard an argument outside his tent. He came out very angry and shot Cozens in the face without warning. This made things even worse. Cheap would not let Cozens get medical help. Cozens took ten days to die from his wound.

Cummins kept changing the boats for an escape plan. The crew's rebellion was only a possibility as long as he worked. But once the schooner was ready, things happened quickly.

Cheap refused to sign a letter from Bulkley. Armed sailors entered his hut on October 9. They tied him up. They said he was their prisoner and they were taking him to England for trial for Cozens' death. Lieutenant Hamilton of the Royal Marines was also held. The crew feared he would resist their plan. Cheap was completely surprised. He did not realize how far things had gone. He said to Lieutenant Baynes, "Well 'Captain' Baynes! You will surely be held responsible for this later."

After the Crew's Disagreement

The Speedwell's Journey

At noon on October 13, 1741, the schooner, now named the Speedwell, began to sail. The cutter and barge went with it. Cheap refused to go. To the relief of the crew, he agreed to be left behind with two marines who had been avoided for stealing food. Everyone expected Cheap to die on the island. This would make their return to England much easier to explain. Bulkley wrote in his journal that day, "This was the last I ever saw of the captain." However, both men would make it back to England alive. Cheap returned about two years after Bulkley.

The journey started badly. After the sails kept tearing, the barge was sent back to the island. There were more supplies there. Two young officers, John Byron and Alexander Campbell, had been tricked into thinking Cheap would be taken home with them. They quietly got onto the barge. They were among the nine who returned. When Bulkley realized they were on board, he tried to get them to come back. But the barge sailed away quickly. Once back at the island, Cheap greeted the barge party. He was happy to hear they wanted to stay with him. By the time Bulkley sailed back to look for the barge and its men, they had all disappeared.

Speedwell and the cutter turned around and sailed south. The journey was very hard, and food was scarce. On November 3, the cutter separated from them. This was serious because it was needed for finding food near the shore. By now, Bulkley was losing hope for the men on the schooner. Most were starving, cold, and had given up. Some days later, they had good news. They saw the cutter and rejoined it. Soon after, at night, the cutter broke free from its tow rope and crashed on the coast. Of the 81 men who had left about two weeks before, ten had already died.

As food ran out, the situation became desperate. Ten men were chosen and made to sign a paper. They agreed to be left on the empty, frozen, swampy southern coast of Chile. This was almost a death sentence. Sixty men stayed on Speedwell. Eventually, the schooner entered the Strait of Magellan. Huge waves threatened the boat with every swell. Men were dying from hunger regularly. Some days after leaving the Strait, the boat moved closer to land to get water and hunt for food. Later, as they took the last of their supplies on board, Bulkley sailed away. He left eight men on the lonely shore 300 miles south of Buenos Aires. This was the second time he left men to what seemed like certain death. Years later, he would meet some of them back in England. Three of the men he left behind made it back to England alive after much effort. Only 33 men remained on Speedwell.

Finally, after a short stop at a Portuguese outpost, Speedwell sailed again. On January 28, 1742, it reached Rio Grande. This was after a journey of over 2,000 miles in an open boat over 15 weeks. Of the 81 men who left the island, 30 arrived at Rio in a very bad state.

Captain Cheap's Group

Twenty men stayed on the island after Speedwell left. Bad weather continued through October and November. One man died from cold after being left for three days on a rock for stealing food. By December, it was decided to launch the barge and the yawl. They would sail up the coast 300 miles to a populated part of Chile. During bad weather, the yawl overturned and was lost. The quartermaster drowned.

There was not enough room for everyone in the barge. Four of the weakest men, all marines, were left on the shore to survive on their own. In his story, Campbell describes what happened: "The loss of the yawl was a great misfortune to us who belonged to her (being seven in number). All our clothes, weapons, etc. were lost with her. The barge could not carry both us and its own company, which was 17 men in total. So, it was decided to leave four of the Marines on this lonely place. This was sad, but we had to do it. And since we had to leave some behind, the marines were chosen. They were not useful on board. What made the case of these poor men even sadder was that the place had no seals, shellfish, or anything they could possibly eat. The captain left them weapons, ammunition, a frying pan, and other needed items."

Fourteen men were now left, all in the barge. After many failed attempts to get around the headland, they decided to return to the island. They gave up all hope of escape. They looked for the four stranded marines, but they had disappeared. Two months after leaving the island, Cheap's group returned. The 13 survivors were close to death. One man died of hunger soon after arriving.

Back at the island, Cheap's health got much worse. His legs swelled to twice their normal size. Byron's later story also criticized him for taking more food than others but doing less work. Fifteen days after returning to the island, the men were visited by native Chono nomads. They were led by Martín Olleta. They were surprised to find people shipwrecked there. After some talking, with the doctor speaking a little Spanish, the Chonos agreed to guide Cheap's group to a small Spanish settlement up the coast. They would use a land route to avoid the peninsula. The shipwrecked men traded the barge for the journey. Iron was very valuable to the Chonos.

Martín Olleta led the survivors through an unusual path across Presidente Ríos Lake in the Taitao Peninsula. Byron gives a detailed story of the journey to the Spanish village of Castro in the Chiloé Archipelago. Alexander Campbell also tells his story. The journey took four months. During this time, another ten men died from hunger and tiredness. Marine Lieutenant Hamilton, young officers Byron and Campbell, and Captain Cheap were the only ones who survived.

Before giving the English to Spanish officials, Olleta's group stopped south of Chiloé Island. They hid all iron objects. This was likely to prevent them from being taken.

The Speedwell Survivors Return to England

The surviving crew members who had left on Speedwell had a difficult time. They eventually found a way to get to Rio de Janeiro on a ship called Saint Catherine. It sailed on March 28, 1742. Once in Rio, problems with officials and other groups kept making their lives difficult. King, the boatswain, caused trouble. He formed a group that often bothered his former shipmates. This made them move to the other side of the city to avoid him. After many times of running from their homes, Bulkley, Cummins, and the cooper, John Young, asked for help from Portuguese officials.

The crew eventually found a way to get to Bahia on a ship called Saint Tubes. It sailed on May 20, 1742. They were happy to leave King behind in Rio. On September 11, 1742, Saint Tubes left Bahia for Lisbon. From there, they boarded HMS Stirling Castle on December 20. They were going to Spithead, England. They arrived on New Year's Day 1743, after being away for more than two years. News of their arrival was also sent to London from the British official in Lisbon.

Lieutenant Baynes rushed ahead of Bulkley and Cummins to the navy office. He gave a report of what happened to the Wager. His report made Bulkley and Cummins look bad, but not himself. Baynes was seen as a weak and not very good officer by everyone who wrote about the shipwreck. Because of Baynes' report, Bulkley and Cummins were held on Stirling Castle for two weeks. The navy decided to release them. They would wait for Anson or Cheap to return before having any formal hearings. When Anson returned in 1744, it was decided that no trial would happen until Cheap returned. Bulkley asked the navy office for permission to publish his journal. They said he could do what he liked. Bulkley released a book with his journal. But some people at first thought he should be punished as a rebel.

Bulkley found work when he took command of a 40-gun privateer ship called Saphire. Soon, his skill and bravery brought him success. He tricked his way around a stronger group of French ships. As a result, Bulkley's adventures were reported in London newspapers. He became somewhat famous. He started to think the navy would soon offer him command of a Royal Navy ship. However, on April 9, 1745, Cheap arrived back in England.

Captain Cheap's Group Survivors Return to England

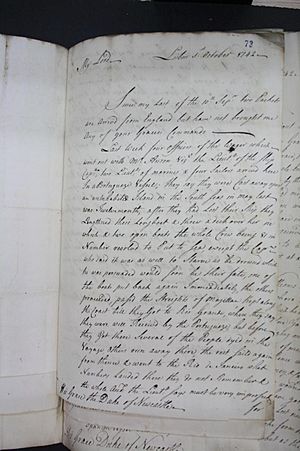

By January 1742 (which was January 1743 in the modern calendar), as Bulkley was returning to England, the four survivors of Cheap's group had spent seven months in Chacao. They were held as prisoners by the local governor. But they were allowed to live with local families and were not bothered. The biggest problem for Byron trying to return to England was an old lady who first took care of him. She and her two daughters liked Byron very much. They did not want him to leave. They convinced the governor to let Byron stay with her for a few extra weeks. He finally left, with many tears. Once in Chacao, Byron was also offered marriage to the richest young woman in town. Her admirer said, "her body was good, she could not be called a regular beauty." This seemed to decide her fate. On January 2, 1743, the group left on a ship going to Valparaíso. Cheap and Hamilton went to Santiago. They were officers and kept their positions. Byron and Campbell were put in jail without ceremony.

Byron and Campbell were kept in a single cell full of insects. They were given very little food. Many local people visited their cell. They paid officials to see the 'terrible Englishmen'. These were people they had heard much about but never seen. However, the harsh conditions moved not only their curious visitors but also the guard at their cell door. He allowed food and money to be brought to them. Eventually, Cheap's whole group made it to Santiago. Things were much better there. They stayed there on parole for the rest of 1743 and 1744.

After two years, the group was offered passage on a ship to Spain. All agreed, except Campbell. He chose to travel by land with some Spanish naval officers to Buenos Aires. From there, he would connect to a different ship also going to Spain. Campbell was very angry that Cheap gave him less money than he gave to Hamilton and Byron. Campbell was thought to be considering marrying a Spanish colonial woman. This was against the rules of the Royal Navy at that time. Campbell was furious about this treatment. He wrote: "...the disagreement between me and the Captain, as already told, and since which we had not talked, made me not want to go home on the same ship with a man who had treated me so badly; but rather to board a Spanish warship then in Buenos Aires."

On December 20, 1744, Cheap, Hamilton, and Byron boarded the French ship Lys. It had to return to Valparaiso after getting a leak. On March 1, 1744 (which was March 1745 in the modern calendar), Lys set out for Europe. After a good trip around Cape Horn, it stopped in Tobago in late June 1745. After getting lost and sailing through a dangerous island chain, the ship headed for Puerto Rico. The crew was worried when they saw empty barrels from British warships. Britain was now at war with France. After barely avoiding capture, the ship made its way to Brest. It arrived on October 31, 1744. After six months in Brest with almost no money, shelter, food, or clothes, the poor group boarded a Dutch ship for England. On April 9, 1745, they landed at Dover. They were three men out of the 20 who had left in the barge with Cheap on December 15, 1741.

News of their arrival quickly reached the navy office and Bulkley. Cheap went directly to London with his version of events. A naval hearing was organized. Bulkley was at risk of severe punishment.

Abandoned Speedwell Survivors Return to England

Eight men were left by Bulkley at Freshwater Bay. This is where the city of Mar del Plata stands today. They were alone, starving, sick, and in a dangerous, remote country. After a month of eating sea lions killed with stones, the group began the 300-mile walk north to Buenos Aires. Their biggest fear was the Tehuelche nomads. After walking 60 miles north in two days, they had to return to Freshwater Bay. This was because there was no water. Once back, they decided to wait for the rainy season before trying again. They settled more at the bay. They built a hut, tamed some wild puppies, and started raising pigs. One night, one of the group saw what they called a 'tiger' watching their hut. Another sighting of a 'lion' soon after made the men quickly plan another attempt to walk to Buenos Aires. (They actually saw a jaguar and a cougar).

One day, when most of the men were out hunting, the group returned. They found that the two men left behind to watch the camp had been killed. The hut was torn down, and all their things were taken. Two other men who were hunting in another area disappeared. Their dogs made their way back to the destroyed camp. The four remaining men left Freshwater Bay for Buenos Aires. They were with 16 dogs and two pigs.

The group eventually reached the mouth of the River Plate. But they could not get through the swamps. They were forced to go back to Freshwater Bay. Soon after, a large group of Tehuelches on horseback surrounded them. They took them all captive. After being bought and sold four times, they were eventually taken to Cangapol. He was a leader who led a group of nomad tribes. When he learned they were English and at war with the Spanish, he treated them better. By the end of 1743, after eight months as captives, they told the chief they wanted to return to Buenos Aires. Cangapol agreed. But he refused to give up John Duck, who was of mixed race. An English trader in Montevideo, hearing of their trouble, paid money for the other three. They were released.

When they arrived in Buenos Aires, the Spanish governor put them in prison. This was after they refused to change their religion. In early 1745, they were moved to the ship Asia. There, they were forced to work. After this, they were put in prison again. They were kept in chains and given only bread and water for 14 weeks. Then, a judge ordered their release. Then Alexander Campbell, another of Wager's crew, arrived in town.

Campbell's Land Journey to Buenos Aires

On January 20, 1745, Campbell and four Spanish naval officers set out across South America. They went from Valparaiso to Buenos Aires. Using mules, the group traveled into the high Andes mountains. There, they faced steep mountains, very cold weather, and sometimes serious altitude sickness. First, a mule slipped on a narrow path and fell onto rocks far below. Then two mules froze to death during a terrible night of blizzards. Another 20 died from thirst or hunger on the rest of the journey. After seven weeks of travel, the group finally arrived in Buenos Aires.

Campbell and the Freshwater Bay Survivors Return to England

It took five months for Campbell to leave Buenos Aires. He was held in a fort twice for several weeks. Eventually, the governor sent him to Montevideo. This was just 100 miles across the River Plate. Here, the three Freshwater Bay survivors, young officer Isaac Morris, sailor Samuel Cooper, and John Andrews, were held as prisoners on the ship Asia. There were also 16 other English sailors from another ship. While his shipmates were treated harshly, Campbell had changed his religion. He was allowed to socialize with various captains in Montevideo.

All four Wager survivors left for Spain on Asia at the end of October 1745. But the trip was not without problems. After three days at sea, 11 Indian crew members went against the Spanish officers. They killed 20 Spaniards and injured another 20. They briefly took control of the ship. Eventually, the Spaniards regained control. They killed the Indian leader Orellana with a 'lucky shot', according to Morris. His followers all jumped overboard rather than surrender.

Asia stopped at the port of Corcubion, near Cape Finisterre, on January 20, 1746. The officials chained Morris, Cooper, and Andrews together and put them in prison. Campbell went to Madrid for questioning. After four months held in terrible conditions, the three Freshwater Bay survivors were eventually released to Portugal. From there, they sailed for England. They arrived in London on July 5, 1746. Bulkley had to face men he thought had died thousands of miles away.

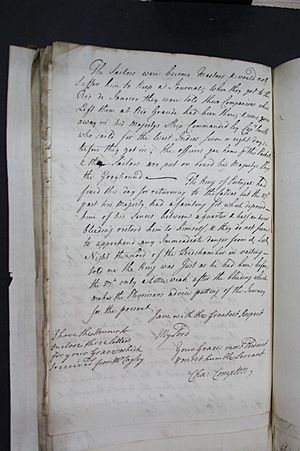

Campbell said he had not joined the Spanish Navy. This seemed true when he arrived in London in early May 1746, shortly after Cheap. Campbell went straight to the navy office. He was quickly dismissed from service for changing his religion. His dislike for Cheap had grown even stronger. After all he had been through, he ended his story: "Most of the difficulties I faced by following Captain Cheap were because I chose to stay with him. In return, the Captain has shown himself to be my greatest enemy. His unfair treatment of me forced me to leave his company. I chose to sail to Europe on a Spanish ship rather than a French one."

A full naval hearing was started to find out what happened to the Wager. This happened once Cheap returned and gave his report to the navy office. All Wager survivors were ordered to report to HMS Prince George for the hearing. When he heard this, Bulkley arranged to have dinner with the Deputy Marshal of the Admiralty. This was the officer who enforced navy commands. Bulkley kept his true identity a secret. He wrote about his conversation with the Deputy Marshal: "I wanted to know his opinion about the Officers of the Wager, since their Captain had come home. I had a close relative who was an Officer who came in the long-boat from Brazil, and it would worry me if he would suffer. His answer was that he believed that we should be punished. To which I replied, for God's Sake for what, for not drowning? And has a person who caused death finally come home to accuse them? I have carefully read the Journal, and cannot believe that they have been guilty of piracy, rebellion, or anything else to deserve it. It looks to me as if their enemies have gone against the power of God, for saving them."

At this point, the Marshal replied: "Sir, they have been guilty of such things to Captain Cheap while he was a prisoner, that I believe the Gunner and Carpenter will be punished if no one else is."

Bulkley then revealed who he was to the Marshal, who immediately arrested him. When he arrived on Prince George, he sent some friends to visit Cheap. He wanted to know Cheap's mood and plans. Their report did not make Bulkley feel better. Cheap was very angry. He told them: Gentlemen, I have nothing to say for or against bad people, until the Day of Trial. Then it is not in my power to stop them from being punished."

Once the main people were secured, the hearing was set for Tuesday, April 15, 1746. Vice Admiral James Steuart led it. Much of what happened on the day land was first seen off Patagonia came out in sworn statements. These included statements from Cheap, Byron, Hamilton, Bulkley, Cummins, and King (who had also returned to England).

Cheap wanted to accuse those who left him on Speedwell of rebellion. But he decided not to. This was because it was suggested that such claims would lead to him being accused of causing Cozens' death. None of the witnesses knew at this point that the navy office had decided not to look into events after the ship crashed.

After hearing the statements and asking questions, the men were all quickly found not guilty of any wrongdoing. Only Lieutenant Baynes was criticized. He was told off for not reporting the carpenter's sighting of land to the captain. He was also criticized for not dropping anchor when ordered.

What Happened Next

The crew members who went against the captain argued that their pay stopped the day their ship crashed. So, they were no longer under naval law. Captain Stanley Walter Croucher Pack, in his book about the event, explains this and the navy office's decision not to investigate events after the Wager was lost: "Their Lordships knew that finding them guilty of rebellion would be unpopular with the country. Things were bad with the Navy in April 1746. Their Lordships were not liked. One reason for this was their harsh treatment of Admiral Vernon, who was popular with the public... The defense the crew had was that their wages automatically stopped when the ship was lost. So, they were no longer under naval law. This idea could lead to problems if a ship was in danger. Anson realized the danger and corrected this idea. In 1747, a law was passed to make sure navy rules applied to crews of ships that were wrecked, lost, or captured. It also said they would keep getting paid under certain conditions... The survivors of the Wager were very lucky not to be found guilty of rebellion. They were found not guilty not only because the navy office was unpopular, but also because public opinion was strong. Their amazing escapes had captured the public's interest."

Cheap was promoted to the rank of post captain. He was given command of the 40-gun ship Lark. This showed that the navy office thought his loyalty was more important than his mistakes. He captured a valuable prize soon after. This allowed him to marry in 1748. He died in 1752.

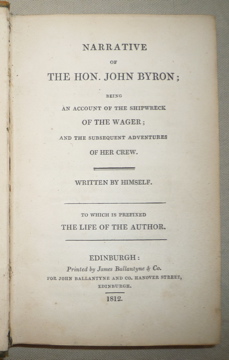

Byron was promoted to the rank of master and commander. He was given command of the 20-gun ship Syren. He eventually became a vice admiral. Byron had a varied and important career. He sailed around the world. He married in 1748 and started a family. He died in 1786. His grandson, George Gordon Byron, became the famous poet Lord Byron.

Baynes' records exist from before Anson's fleet sailed. After he returned to England, he never served at sea again. Instead, in February 1745, before the hearing, he was given a job on land. He ran a naval supply yard in Clay near the Sea, Norfolk. He stayed in this job until he died in 1758.

Soon after the hearing, Bulkeley was offered command of the cutter Royal George. He turned it down. He thought it was "too small to stay at sea." He was right. The ship later sank in the Bay of Biscay. Everyone on board was lost.

Campbell finished his story of the Wager event by saying he had not joined the Spanish Navy. However, in the same year his book was published, a report was made against him. Commodore Edward Legge reported that he met Alexander Campbell in a Portuguese port. Campbell was formerly of the Royal Navy and HMS Wager. He was signing up English sailors and sending them to Cadiz to join the Spanish service.

|

See also

In Spanish: Motín del HMS Wager para niños

In Spanish: Motín del HMS Wager para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |