American urban history facts for kids

American urban history is the study of how cities in the United States have grown and changed over time. It looks at everything from their beginnings to how they look and work today. For a long time, people mostly wrote about their own city's history. But starting in the 1920s, experts like Arthur Schlesinger, Sr. began to compare cities. They wanted to see what cities had in common and how they developed.

Some people in American history, like Thomas Jefferson, didn't like cities much. They preferred farming life. But cities have always been important. Today, studying cities is a big and exciting field. Scholars are trying to understand how cities as places connect with the process of urbanization. They also study the many different experiences people have in cities.

Contents

How We Study City History

American urban history is part of the larger history of the United States. It's also a branch of Urban history, which looks at how cities and towns develop. This field often uses ideas from many different subjects. These include social history (how people lived), architectural history (how buildings changed), urban sociology (how city groups interact), and urban geography (how cities are laid out).

From the 1920s to the 1990s, many important books on urban history came from students of Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. and Oscar Handlin at Harvard University. Schlesinger and his students focused on groups of people, not just individuals. Handlin added a focus on different ethnic groups, like Germans, Irish, or Jewish people. The idea was that the city environment shaped their history and how they saw the world.

New Ways to Study Cities

In the 1960s, a new way of studying cities appeared. It was called "new urban history." This method used statistics and computers to look at census data, person by person. It focused on how people moved around cities and changed their social standing. Many studies were done, but it was hard to understand what the results really meant. The main supporter of this method, Stephan Thernstrom, later said it wasn't very useful.

Overall, urban history grew quickly in the 1970s and 1980s. This was because more people became interested in social history. However, since the 1990s, fewer young scholars have chosen to study this field.

Why Cities Are Important

Historian Richard Clement Wade explained why cities are so important in American history.

- Cities were key places for the growth of the American West. This was especially true for cities along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.

- Cities, like Boston, were where the American Revolution began.

- Rivalry between cities, such as Baltimore and Philadelphia, helped create new ideas and economic growth. This was especially true for railroads.

- Cities encouraged new businesses, especially for trade, banking, and the start of the factory system after 1812.

- The fast-growing railroad system after 1840 connected major cities. These cities then became centers for trade.

- Railroads helped cities like Atlanta and Chicago control larger surrounding areas.

The Southern states didn't develop many cities. This made them weaker during the American Civil War. Cities like Baltimore and St. Louis, which were on the border, stayed with the Union. Cities were also places where democracy grew, with strong political groups. They were also home to many immigrant groups, like the Irish and Jewish people. Cities were strongholds for labor unions in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Historian Zane Miller said that urban history became exciting again in the mid-20th century. People realized that cities were important for culture, not just art. Historians began to focus on how cities allowed for many different ways of life. By the 1990s, there was more focus on minority groups and leisure activities.

Doubts About Cities

Many American thinkers have not liked cities. They often believed that the natural, rural areas were better and more moral. They thought cities were full of dishonest people and crime. Poets often described cities as ugly places with inequality and problems. They saw city people as too competitive and less natural.

Early American Cities

Historian Carl Bridenbaugh studied five important colonial cities: Boston, Newport, New York City, Philadelphia, and Charles Town (Charleston). He said they grew from small villages to become leaders in trade and immigration. They also spread new ideas in medicine and technology. These cities helped create an American education system and cared for people needing help.

These cities were not as grand as European cities. But they had unique American features. There was no powerful upper class or official church. The colonial governments were less controlling than in Europe. They tried new ways to raise money and solve city problems.

Colonial cities were more democratic than European ones. More men could vote, and social classes were not as strict. Printers, especially newspaper editors, had a big role in shaping public opinion. Lawyers often moved between politics and their jobs. Bridenbaugh believed that by the mid-1700s, middle-class business owners, professionals, and skilled workers led the cities. He described them as "sensible, shrewd, frugal, ostentatiously moral, generally honest," and public-spirited. He argued their desire for money led to a desire for political power.

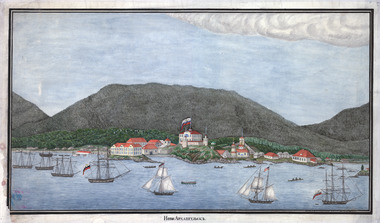

European powers set up small towns as centers for government and trade. Examples include Spanish towns like Santa Fe, New Mexico and Los Angeles. French towns included New Orleans and Detroit. The Dutch founded New Amsterdam (now New York City). The Russian town of New Archangel (now Sitka) was also an early settlement. When these areas became part of the United States, these towns grew even more.

Charleston, South Carolina, was one of the most important Southern cities before the Civil War. It grew as a port for shipping rice and cotton. This brought many cultural and social opportunities. The city had many wealthy merchants and plantation owners. The first theater in America was built in Charleston in 1736. Many groups formed societies to help each other, like the French Huguenots and German immigrants. The Charleston Library Society was started in 1748. This group also helped create the College of Charleston in 1770, which is one of the oldest colleges in the U.S.

By 1775, Philadelphia was the largest city with 40,000 people. New York had 25,000, Boston 16,000, Charleston 12,000, and Newport 11,000. All these were seaports with many sailors and business visitors. Before the Revolution, 95% of Americans lived outside cities. The British could capture the cities but struggled to control the countryside. Historian Benjamin Carp highlights the role of waterfront workers, taverns, and churches in the American Revolution.

Historian Gary B. Nash stresses the role of working-class people in northern ports. He argues that skilled workers in Philadelphia took control of the city around 1770. They pushed for a more democratic government during the Revolution.

The New Nation, 1783–1815

Cities helped start the American Revolution, but they suffered during the war (1775–83). The British Navy blocked their ports. The British also occupied cities like New York (1776–83), Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston for a while. During these times, cities were cut off from trade. When the British left in 1783, many wealthy merchants moved away.

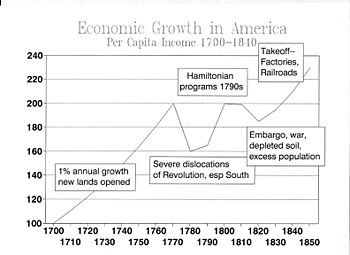

The older cities rebuilt their economies. Growing cities included Salem, Massachusetts (which started trade with China), and Baltimore, Maryland. In 1791, the government set up a national bank, and local banks grew in all cities. Business owners helped cities become very prosperous.

City merchants and bankers knew the old government system was weak. When it was time to approve the new, stronger United States Constitution in 1788, all cities, North and South, voted for it. Rural areas were divided.

Philadelphia was the national capital until 1800. It was known as a clean, well-run, and elegant city. Washington, D.C., built in a swampy area, was not as well-liked.

From 1793, a long war between Britain and France began. The U.S. traded with both sides as a neutral country. This led to problems, like the Quasi-War with France (1798–99). Later, the U.S. fought Britain in the War of 1812. These wars hurt trade for American cities.

However, there were good things happening too. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 opened up huge new lands to the West. New Orleans and St. Louis joined the U.S. New cities like Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and Nashville also grew. Historian Richard Wade emphasized how important these new cities were for westward expansion. They were centers for transportation, migration, and funding for settlers.

The new western regions had few roads but many rivers. Everything flowed downstream to New Orleans. After 1820, steamboats made it possible to move goods upstream to new settlements. The Erie Canal helped Buffalo become a key city for lake transportation. This led to the growth of Cleveland, Detroit, and especially Chicago.

Fast City Growth, 1815–1860

| City | 1820 | 1840 | 1860 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boston and its suburbs | 63,000 | 124,000 | 289,000 |

| New York | 152,000 | 391,000 | 1,175,000 |

| Philadelphia | 137,000 | 258,000 | 566,000 |

New York City grew much faster than other cities. Its population went from 96,000 in 1810 to 1,080,000 in 1860. Philadelphia had 566,000 people, Baltimore 212,000, and Boston 178,000 (289,000 with suburbs). Historian Robert Albion points to four reasons for New York's success:

- It had an efficient auction system for selling imported goods.

- It set up regular ship service across the Atlantic to England.

- It developed a large coastal trade, bringing Southern cotton to New York for export.

- It supported the Erie Canal, which opened up new markets in upstate New York and the Midwest.

Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore tried to compete with their own canals and railroads, but they never caught up. The Erie Canal helped Buffalo become a major hub for lake travel. This led to the growth of Cleveland, Detroit, and Chicago. Manufacturing wasn't the main reason for growth in the largest cities then. Factories were mostly built in smaller towns, especially in New England, where they could use water power.

City Leadership

America's financial, business, and cultural leaders were mostly in the three or four largest cities. But political leadership was spread out. It was divided between Washington, D.C., and state capitals. Many states purposely moved their capital out of their largest city.

Academic and scientific leadership was not strong in the U.S. until the late 1800s. Then, it began to focus in universities. Some major research universities were near large cities, like Harvard University (Boston) and Columbia University (New York). But most were in smaller cities or towns, like Yale in New Haven, Connecticut.

Civil War

Cities played a big role in the American Civil War. They provided soldiers, money, training camps, supplies, and media support for the Union.

In the North, people were unhappy with the 1863 draft law. This led to riots in several cities. The most important were the New York City draft riots in July 1863. Workers fought police and soldiers. The protests started about the draft but quickly turned into attacks on Black people in New York City.

A study of small Michigan cities, Grand Rapids and Niles, showed a strong feeling of nationalism in 1861. Everyone was excited for the war. But by 1862, many soldiers were dying. The war also became more about freeing enslaved people. Some Democrats called the war a failure.

Southern Cities in the War

Cities were much less important in the mostly rural Confederacy. When the war began in 1861, Union forces took over the largest cities in slave states. These included Washington, Baltimore, Louisville, and St. Louis. New Orleans, the biggest Confederate city, was captured in early 1862. Nashville fell in 1863. All these cities became important centers for the Union army.

By summer 1861, all remaining Confederate ports were blocked. This stopped normal trade. Only very expensive blockade runners could get through. The largest remaining Confederate cities were Atlanta, a railroad center destroyed in 1864, and Richmond, the capital, which held out until the end.

Food shortages and high prices hit Confederate cities hard. In 1864, when bacon became very expensive, poor white women in Richmond and Atlanta rioted. They broke into shops to take food. These women were angry about the lack of help from the state and about greedy merchants.

In 1860, the eleven Confederate states had 297 towns and cities with 835,000 people. Union forces occupied 162 of these cities at some point. Eleven cities were destroyed or badly damaged, including Atlanta, Charleston, Columbia, and Richmond.

City Growth in the Late 1800s

City Streets and Traffic

In the late 1800s, streets were mostly dirt or gravel. They wore down unevenly and created potholes. In 1900, Manhattan alone had 130,000 horses pulling streetcars and wagons. They left a lot of waste. Horses were slow, so people could easily cross busy streets.

Smaller towns kept using dirt and gravel roads. But larger cities wanted better streets. They started using wood or granite blocks. By 1890, a third of Chicago's streets were paved, mostly with wooden blocks. Brick was a good option, but asphalt was even better. Washington, D.C., paved many of its streets with asphalt by 1882. By the end of the century, American cities had millions of square yards of asphalt paving.

In the biggest cities, street railways were built above ground to make them faster and safer. Street-level trolleys carried passengers at 12 miles per hour for 5 cents. They became the main way for middle-class shoppers and office workers to get around. This lasted until people bought cars after 1945. Working-class people usually walked to nearby factories and small local stores.

City streets became busy with faster and more dangerous vehicles. Underground subways were a solution. Boston built one in the 1890s, and New York followed a decade later.

The New West

After 1860, railroads moved westward into new areas. They built towns to support construction crews, train workers, and passengers. Towns at the end of major cattle drives from Texas were known for gunfights and disorder, though these were often exaggerated in stories.

In the South, there were few large cities. Railroads arrived in Texas in the 1880s and shipped cattle out. Passenger trains were often targets for gangs.

Denver's economy before 1870 was based on mining. Then it grew by expanding its role in railroads, trade, and manufacturing. Between 1870 and 1890, its manufacturing output soared, and its population grew 20 times to 107,000. Denver attracted miners, workers, and travelers. It had many saloons and gambling places. The city also boasted fine theaters, like the Tabor Grand Opera House built in 1881. By 1890, Denver was the 26th largest city in America. Its growth attracted many wealthy people and their mansions.

Butte, Montana, with its large copper mountain, was a huge and lively mining town. It had many different ethnic groups. Irish Catholics often controlled politics and good jobs at the Anaconda Copper company. City leaders opened a public library in 1894 to promote middle-class values. Butte also had a large opera house for performances.

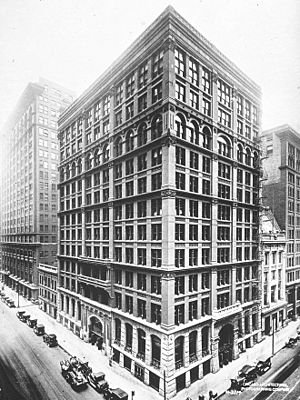

Skyscrapers and Apartment Buildings

In Chicago and New York, new inventions led to the rise of the skyscraper in the 1880s. This was a unique American style. Building them required two major inventions: the elevator and the steel beam. The steel skeleton, developed in the 1880s, replaced heavy brick walls. Skyscrapers also needed complex systems for air, heat, light, and plumbing.

City housing came in many styles. Most attention was on tenement houses for working-class people and apartment buildings for the middle class. Apartment buildings came first. Middle-class workers realized they didn't need or couldn't afford single-family homes in the city. Boarding houses weren't good for families, and hotels were too expensive. In smaller cities, many apartments were above stores. Residents paid rent and didn't own their apartments until later.

Luxury apartment buildings like the Stuyvesant (1869) and The Dakota (1884) in New York offered full-time staff for upkeep and security. Less fancy middle-class apartments had gas lighting, elevators, good plumbing, and central heating. Boston built many "Triple-Deckers" between 1870 and 1920. These were modern buildings with a large apartment on each floor. Chicago built thousands of apartment buildings, with the nicer ones near the lake. In every city, apartment buildings were built along streetcar lines. Middle-class people rode the streetcar to work, while working-class people walked.

Working-class people lived in crowded tenement houses. These were cheap and easy to build, often filling almost the entire lot. They were usually five stories tall, with four apartments on each floor. There was little fresh air or sunlight. Until reforms in 1879, New York tenements didn't have running water or indoor toilets. Garbage collection was often bad. Rents were cheap, but conditions were tough. Most tenements lasted until the 1950s.

The City's Appeal

Many Americans, especially those from rural areas, didn't trust cities. In 1881, a newspaper warned young men to stay on the farm. It said cities lacked fresh food, good water, and proper sleep. It also claimed cities were bad for moral growth. The paper described city people as dishonest. It asked why a "sturdy farmer" would want the "follies of the madding crowd in the Gay Metropolis."

But a Milwaukee newspaper editor responded in 1871. He said ambitious young men couldn't be stopped from moving to cities. He wrote that the city "draws him like a magnet." Sooner or later, he would be "sucked into one of the great centers of life."

City Reformers

In the late 1800s, many reformers tried to improve cities.

- The Mugwumps were Republicans who wanted national reforms in the 1870s and 1880s.

- "Goo Goos" were local reformers who wanted "good government" no matter the political party. They focused on city cleanliness, better schools, and lower trolley fares. They especially wanted a system where city jobs were given based on skill, not political favors.

These groups often formed short-lived city organizations. They sometimes won elections but were rarely reelected. Political parties often made fun of them for trying to be independent.

By the 1890s, "structural reformers" emerged. They were more successful and started the Progressive Era. They used national organizations and focused on honesty, efficiency, and expert decision-making. "Efficiency" was their main goal. They believed political machines wasted tax money by creating useless jobs.

Social reformers also appeared in the 1890s, like Jane Addams at Hull House in Chicago. They cared less about government structure and more about housing for workers, child labor, and welfare. Protestant churches also had reformers, mostly women, who wanted to reduce the negative influence of saloons.

Rural America largely supported the idea of banning alcohol. But they rarely succeeded in larger cities, where German and Irish groups strongly opposed it. However, the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) became well-organized in cities. They taught middle-class women how to organize and spread their message. Many WCTU members later joined the women's suffrage movement, which fought for women's right to vote. Women gained the right to vote in state after state, and finally nationwide in 1920.

School reform was also important. Local politicians often used school jobs to help their party, not the students. Historian David Tyack found that reformers wanted to replace this system with a more professional one.

The 20th Century

From 1890 to 1930, larger cities were the center of national attention. Skyscrapers and tourist spots were widely advertised. Suburbs existed, but they were mostly places where people lived and commuted to the central city for work. San Francisco was important in the West, Atlanta in the South, and Boston in New England. Chicago, a railroad hub, was key in the Midwest. New York City led the entire nation in communication, trade, finance, and culture. Over a fourth of the 300 largest companies in 1920 had their main offices in New York City.

The Progressive Era: 1890s–1920s

During the Progressive Era, a group of middle-class voters, experts, and reformers worked together. They wanted to reduce waste, inefficiency, and corruption in American cities. They used scientific methods, pushed for compulsory education, and created new ways to manage cities.

Detroit, Michigan, led the way. Republican mayor Hazen S. Pingree brought together this reform group. Many cities set up offices to study local government budgets and structures. Progressive mayors were important in cities like Cleveland, Los Angeles, and Memphis, Tennessee. In Illinois, Governor Frank Lowden reorganized the state government. Wisconsin was a stronghold for Robert La Follette, who used the state university for new ideas.

One big change happened in Galveston, Texas. A terrible hurricane and flood overwhelmed the city. Reformers got rid of political parties in city elections. They set up a five-person commission of experts to rebuild the city. The Galveston plan was simple and efficient. It reduced corruption and gave more power to middle-class reformers. Many other cities copied this plan, especially in the West. By 1914, over 400 cities had nonpartisan elected commissions. Dayton, Ohio, after a flood in 1913, created the idea of a paid, non-political city manager. This person was hired by the commissioners to run the city's departments.

City Planning

The Garden city movement came from England. It led to the "Neighborhood Unit" way of developing areas. In the early 1900s, cars became common. People worried about pedestrians getting hurt. The solution, first seen in Radburn, New Jersey, was the Neighborhood Unit. Houses faced a common public path instead of the street. The neighborhood was built around a school. This was meant to give children a safe way to walk to school.

The Great Depression

American cities had grown strong and prosperous in the 1920s. Large-scale immigration had mostly stopped by 1914. So, ethnic communities became more stable. People generally moved up in society. The high school system was growing fast. After the stock market crash in October 1929, the country became very pessimistic. Businesses and people cut back on spending.

The economic damage to cities was severe. Private construction dropped by 80 to 90 percent. Cities and states started their own construction projects in 1930. These became a key part of the New Deal. But private construction didn't fully recover until after 1945. Many landlords lost rental income and went bankrupt.

After construction, heavy industry suffered. This included making cars, machinery, and refrigerators. Unemployment was higher in manufacturing centers in the East and Midwest. It was lower in the South and West, which had less manufacturing.

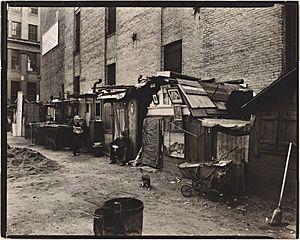

One clear sign of the depression was the rise of Hoovervilles. These were shacks made of cardboard, tents, and wood built by homeless people on empty lots. Residents begged for food or went to soup kitchens. The name "Hooverville" was a sarcastic reference to President Herbert Hoover, whom many blamed for the depression.

Unemployment reached 25 percent in 1932–33, but it varied. Job losses were less severe for women than men. They were also less severe in industries like food and clothing, in service jobs, and in government jobs. Unskilled men in inner cities had much higher unemployment rates. Young people struggled to find their first jobs. Men over 45 who lost their jobs rarely found new ones.

Millions were hired during the Great Depression. But men with fewer skills were often not hired and faced long-term unemployment. The migration of farmers and townspeople to big cities in the 1920s suddenly reversed. Unemployment made cities unattractive. Many people returned to their relatives in rural areas, where food was more plentiful.

City governments in 1930–31 tried to help by expanding public works projects. President Herbert Hoover strongly encouraged this. However, tax money was falling, and cities and private charities were overwhelmed. By 1931, they couldn't provide much more help. They offered the cheapest relief: soup kitchens. After 1933, new sales taxes and federal money helped cities financially. But budgets didn't fully recover until 1941.

Federal programs started by Hoover and expanded by President Roosevelt's New Deal used huge construction projects. They aimed to boost the economy and solve unemployment. Agencies like the CCC and WPA built and repaired public buildings and roads. They provided unskilled jobs for long-term unemployed men.

Democrats won elections easily in 1932, 1934, and 1936. President Roosevelt was very popular in urban America. Key groups supporting him were low-skilled ethnic groups, especially Catholics, Jews, and Black people. Democrats promised and delivered things like jobs and support for labor unions. City political machines were stronger than ever. They helped families get relief.

Roosevelt won the votes of almost every group in 1936. This included taxpayers, small businesses, and the middle class. However, Protestant middle-class voters turned against him after the recession of 1937–38. Historically, local political machines wanted to control their areas and city elections. The fewer people who voted, the easier it was to control. But for Roosevelt to win the presidency, he needed large majorities in cities to overcome rural votes. The machines helped him achieve this.

In the 1936 election, 82% of the 3.5 million voters on relief payrolls voted for Roosevelt. Fast-growing labor unions, mostly in cities, gave 80% of their votes to Roosevelt. So did Irish, Italian, and Jewish communities. Overall, the nation's 106 cities with over 100,000 people voted 70% for Roosevelt in 1936.

In 1938, Republicans made a comeback. Roosevelt's efforts to remove political opponents failed. A group of Northern Republicans and Southern Democrats took control of Congress. They stopped the expansion of New Deal ideas. Roosevelt won in 1940 thanks to his support in the South and in cities. In the North, cities over 100,000 gave Roosevelt 60% of their votes.

With the start of full war preparations in summer 1940, city economies bounced back. Even before Pearl Harbor, the government invested heavily in new factories. They funded round-the-clock production of war materials. This guaranteed jobs for anyone who wanted one. The war brought back prosperity and hope across the nation. It had the biggest impact on West Coast cities like Los Angeles, San Diego, and Seattle.

The 21st Century

At the start of the 21st century, many cities in the South and West grew a lot. This trend continued from the late 20th century, when much growth happened in the Sunbelt region. Texas, in particular, has seen huge growth in the 21st century. Cities like Austin, San Antonio, Dallas, Fort Worth, and Houston are often ranked as the fastest-growing cities in the country.

Other Southern cities that have grown a lot recently include Atlanta, Washington, Tampa, Orlando, Miami, Nashville, Charlotte, and Raleigh. Western cities have also grown, with places like Seattle, Phoenix, Denver, and Las Vegas seeing many new residents. Smaller cities in the South and West have also grown, such as Charleston, Myrtle Beach, and Boise.

However, some cities in the South and West have grown slowly or even lost people. These include Los Angeles, Memphis, and parts of the San Francisco Bay Area. The San Francisco area still has overall growth, but some parts are losing residents. This is due to the high cost of living. Meanwhile, cities in the Rust Belt, like Detroit, Cleveland, St. Louis, and Chicago, have also seen little or no population growth. Many people from these areas are moving to the growing cities in the South and West.

Starting in the late 20th century and continuing into the 21st century, many cities began creating new public transportation systems. After many public transit systems, like streetcars, were removed in the 1950s, cars became the main way to get around. But many cities, especially in the 21st century, have started building, rebuilding, or expanding public transportation. This helps with problems like traffic jams and air pollution from cars.

Many cities have added new light rail systems, like Phoenix's Valley Metro Rail or Charlotte's Lynx Blue Line. Other cities have expanded their existing systems with new lines, like the Expo Line in Los Angeles. Modern streetcars have also been built in cities like Atlanta and Dallas. Some cities have even rebuilt their old-style streetcars, like Tampa with its TECO Line Streetcar that opened in 2002. New commuter rail systems have been built in cities like Orlando and Seattle. Overall, public transportation is a big focus for 21st-century American cities.

|

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |