Ancient Egyptian architecture facts for kids

|

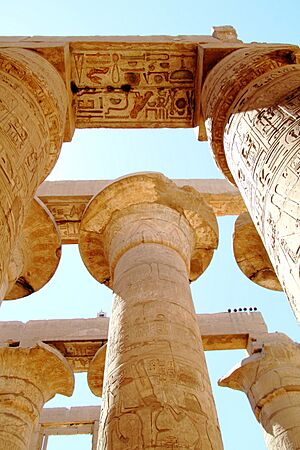

Top: Great Pyramid of Giza (c. 2589–2566 BC); Centre: Columns of the Great Hypostyle Hall from the Temple of Karnak (c. 1294–1213 BC); Bottom: Temple of Isis from Philae (c. 380 BC – 117 AD)

|

|

| Years active | c. 3100 BC – 300 AD |

|---|---|

For over 3,000 years, ancient Egypt was a powerful civilization. Its history had many changes and important periods. Because of this, ancient Egyptian architecture isn't just one style. It's a mix of styles that changed over time, but they all shared some common features.

Most of the buildings that still stand today are religious temples and tombs. These structures often kept traditional designs. The most famous examples of Egyptian architecture are the amazing Egyptian pyramids and the mysterious Sphinx. We also know a lot from studying ancient temples, palaces, tombs, and strong fortresses.

Ancient Egyptians mostly built with materials found nearby. They used mud brick and limestone. Skilled workers and craftsmen built these structures. For huge buildings, they used a method called post and lintel construction. This is like using strong vertical posts to hold up horizontal beams. Many buildings were also carefully lined up with the stars and planets. Columns often had decorative tops, called capitals. These capitals looked like important Egyptian plants, such as the papyrus plant.

Egyptian building styles have inspired people around the world. They first influenced Greek architecture. Then, in the 1800s, there was a big interest in ancient Egypt, called Egyptomania. This led to Egyptian designs appearing in many new buildings.

Contents

Exploring Ancient Egyptian Architecture

Building Materials and Methods

Because wood was scarce, ancient Egyptians mainly used two building materials. These were sun-baked mud bricks and stone. Limestone was the most common stone, but they also used sandstone and granite.

From the Old Kingdom period onwards, stone was mostly saved for important tombs and grand temples. Mud bricks were used for many other buildings. This included royal palaces, strong fortresses, town walls, and smaller buildings around temples.

The inside of the pyramids was often made from local stone, mud bricks, sand, or gravel. But for the outer layer, they used special stones. These stones had to be brought from far away. White limestone from Tura and red granite from Upper Egypt were popular choices.

Ancient Egyptian homes were built from mud. Workers gathered mud from the banks of the Nile River. They put it into molds and let it dry in the hot sun. This made the bricks hard and ready for building. For royal tombs like pyramids, the outer bricks were carefully shaped and polished.

Many ancient Egyptian towns have disappeared. They were often built near the Nile Valley's farming areas. Over thousands of years, the river's bed rose, causing floods. Also, farmers sometimes used the old mud bricks as fertilizer. Some towns are now hidden under newer buildings.

However, Egypt's dry, hot climate helped preserve some mud brick structures. Examples include the village of Deir el-Medina and the town of Kahun. Strong fortresses at Buhen and Mirgissa also survived. Many temples and tombs lasted because they were built on high ground, safe from floods, and made of stone.

So, we learn most about ancient Egyptian architecture from their religious monuments. These are huge buildings with thick, sloped walls and few windows. This style might have helped make mud walls more stable. The carvings and decorations on stone buildings might also have come from earlier mud wall designs.

Even though the arch was known during the Fourth Dynasty, most large buildings used post and lintel construction. This means flat roofs made of huge stone blocks rested on outer walls and closely placed columns.

-

A winged sun carving on a cavetto from the Medinet Habu temple. This symbol represented the falcon god Horus, protecting the temple entrances.

Decorations and Symbols

Both the inside and outside walls of buildings were covered with amazing art. This included columns and pillars. They featured hieroglyphic writings and colorful pictures. These were often painted in bright colors.

Many Egyptian decorations had special meanings. For example, the scarab beetle was a sacred symbol. The solar disk and the vulture also held deep meaning. Other popular designs included palm leaves, the papyrus plant, and lotus flowers.

Hieroglyphs were not just for decoration. They also recorded important historical events and magical spells. These pictures and carvings help us understand how ancient Egyptians lived. They show us their social ranks, battles, and religious beliefs. This is especially true when exploring the tombs of important officials.

Ancient Egyptian temples were often built to line up with important events in the sky. These included solstices (the longest or shortest day) and equinoxes (when day and night are equal). This required very careful measurements. Sometimes, the Pharaoh himself would take part in these special ceremonies.

Magnificent Columns

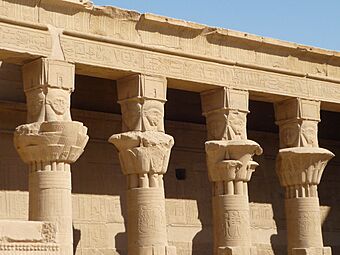

Around 2600 BC, the famous architect Imhotep started using stone columns. These columns were carved to look like bundles of plants. They often resembled papyrus, lotus, and palm plants. Later, columns with many flat sides were also common. These designs likely came from older shrines made of reeds.

Carved from solid stone, these columns were beautifully decorated. They featured carved and painted hieroglyphs, important texts, and images from religious ceremonies. You can see famous Egyptian columns in the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak. There, 134 columns stand in 16 rows. Some of these columns are as tall as 24 meters!

One very important type is the papyriform column. These columns first appeared in the 5th Dynasty. They look like bundles of lotus or papyrus stems tied together with bands. The top part, called the capital, swells out like a flower bud, rather than opening wide. The base of the column tapers down like a lotus stem. It often has repeated decorations of small leaf-like parts called stipules.

At the Luxor Temple, some columns look like bundles of papyrus. This might symbolize the marshy lands from which ancient Egyptians believed the world was created.

-

Drawings of different types of column tops, called capitals. These were made around 1849–1859 by the Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius.

-

Papyrus-shaped columns inside the Luxor Temple.

Ancient Egyptian Gardens

Ancient Egypt had three main types of gardens: temple gardens, private gardens, and vegetable gardens.

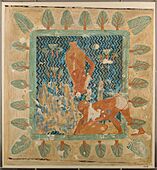

Some temples, like those at Deir el-Bahri, had groves of trees. The sacred Ished Tree (Persea) was especially important. We know about private pleasure gardens from a model found in a tomb from the 11th Dynasty. Tomb paintings from the New Kingdom also show them. These gardens usually had high walls, many trees and flowers, and shady spots.

People grew plants for their fruits and pleasant smells. Popular flowers included cornflowers, poppies, and daisies. The pomegranate, brought to Egypt in the New Kingdom, became a favorite shrub. Wealthy people often had gardens with a decorative pool. This pool would hold fish, waterfowl, and water-lilies.

Vegetable gardens, whether private or belonging to temples, were laid out in squares. Water channels divided these squares. They were always located close to the Nile River. Workers watered them by hand or, later, using a device called a shaduf.

-

A model of Meketra's house and garden from his tomb at Thebes. It shows a shady grove of trees around a central garden. Made around 1981–1975 BC, it is now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

A fresco showing the pool in Nebamun's estate garden. Created around 1350 BC, it is now in the British Museum.

Old Kingdom Structures

Mastaba Tombs

Archaeologists believe that large stone monuments in the Sahara region, built as early as 4700 BCE, might have inspired the mastabas and pyramids of ancient Egypt.

Mastabas were early burial tombs, often for royal families. Many were built along the Nile River. Their design changed over time. Early mastabas of the First Egyptian Dynasty were made with stepped bricks. By the Fourth Dynasty, they used stone instead of bricks. The stepped design was meant to protect the tomb. Layers of brickwork were placed around the base to prevent damage.

Old Kingdom mastabas had a pyramid-like shape. This design was mainly for kings and their families. These tombs were rectangular with slanted walls. They used both stone and brick. The main direction of the structure was North-South. Inside, a mastaba had an offering chamber, statues for the dead, and a vault below for the sarcophagus. By the end of the Old Kingdom, mastabas were no longer used for royal burials.

The Step Pyramid at Saqqara

Egypt's oldest monumental stone building is the Stepped Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara. It was built around 2650 BC. The architect Imhotep is credited with its design. This tomb marks the beginning of pyramid tombs and is one of the earliest large stone structures in history.

Its design changed the simple, flat mastaba tomb. Imhotep stacked several mastabas, each smaller than the one below, creating a stepped shape. This achievement also showed the new importance of using carefully shaped stone as a building material.

How Pyramids Developed

The main period of pyramid building began around 2640 BC with King Snefru. He started building several pyramids, trying out new designs. His first two pyramids, at Meidum, were stepped pyramids, similar to those from the earlier Third Dynasty and Saqqara.

Then came a big change: the first true pyramid with smooth, straight sides. The first attempt was the Bent Pyramid. It's called "bent" because its angle was changed during construction to prevent it from collapsing. The second attempt was successful, creating the Red Pyramid. Both are located at Dahshur. During this time, tomb chambers also became more complex, and decorations improved.

The Giza Pyramid Complex

The Giza Necropolis is on the Giza Plateau, just outside Cairo, Egypt. This group of ancient monuments is about 8 kilometers (5 miles) into the desert from the old town of Giza. It's about 20 kilometers (12 miles) southwest of Cairo's city center.

This ancient Egyptian burial ground includes the Pyramid of Khufu (also known as the Great Pyramid of Giza), the slightly smaller Pyramid of Khafre, and the smaller Pyramid of Menkaure. There are also several smaller "queens" pyramids, the famous Great Sphinx, and hundreds of mastaba tombs.

The pyramids, built in the Fourth Dynasty, show the great power of the pharaohs and their religion. They served as burial sites and helped keep the pharaohs' names alive forever. Their huge size and simple design show the amazing skill of Egyptian engineers. The Great Pyramid of Giza, finished around 2580 BC, is the oldest and largest pyramid in the world. It is the only surviving wonder of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

The pyramid of Khafre was likely finished around 2532 BC. Khafre built his pyramid next to his father's. It's not as tall, but he made it look taller by building it on higher ground. Khafre also ordered the carving of the giant Sphinx to guard his tomb. The Sphinx has a human face, possibly the pharaoh's, on a lion's body. It is carved from the limestone bedrock and stands about 20 meters (65 feet) tall. Menkaure's pyramid, dating to around 2490 BC, is 65 meters (213 feet) high, making it the smallest of the Great Pyramids.

Some stories say pyramids have many confusing tunnels to trick robbers. This isn't true. The passages inside pyramids are quite simple, usually leading directly to the tomb. However, the pyramids' immense size attracted robbers who sought the wealth inside. This meant many tombs were robbed soon after they were sealed.

New Kingdom Temples and Tombs

Luxor Temple

The Luxor Temple is a huge ancient Egyptian temple complex. It sits on the east bank of the River Nile in the city now called Luxor (ancient Thebes). Building work started during the reign of Amenhotep III in the 14th century BC, during the New Kingdom.

Later, Horemheb and Tutankhamun added columns, statues, and carvings. King Akhenaten had earlier removed his father's name carvings and built a shrine to the sun god Aten. But the biggest expansion happened under Ramesses II, about 100 years after the first stones were laid. Luxor Temple is special because only two pharaohs left their main mark on its design.

The temple begins with a 24-meter (79-foot) high First Pylon, built by Ramesses II. This pylon was decorated with scenes of Ramesses's military victories, especially the Battle of Qadesh. Later pharaohs also recorded their wins there. This main entrance originally had six huge statues of Ramesses. Only two seated statues remain today. Visitors can also see a 25-meter (82-foot) tall pink granite obelisk. It was one of a pair until 1835, when the other was moved to Paris.

Through the pylon gateway is a courtyard with columns, also built by Ramesses II. This area was built at an angle to the rest of the temple. This was probably to fit three older shrines in the northwest corner. After this courtyard comes a long hallway built by Amenhotep III. It's 100 meters (328 feet) long and lined with 14 papyrus-capital columns. Carvings on the walls show the stages of the Opet Festival. These decorations were added by Tutankhamun, though his names were later replaced with Horemheb's.

Beyond the colonnade is another courtyard with columns, from Amenhotep's original design. The best-preserved columns are on the eastern side, where you can still see traces of their original color. The southern side of this courtyard leads into a 36-column hypostyle court. This is a roofed space supported by many columns. It leads to the temple's darker inner rooms.

Temple of Karnak

The Karnak temple complex is on the Nile River banks, about 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles) north of Luxor. It has four main parts: the Precinct of Amon-Re, the Precinct of Montu, the Precinct of Mut, and the Temple of Amenhotep IV (which was taken apart). There are also smaller temples and shrines outside the main walls. Avenues of sphinxes with ram heads connect some of the precincts and Luxor Temple.

This temple complex is very important because many rulers added to it, especially every ruler of the New Kingdom. The site covers over 80 hectares (200 acres). It includes many pylons (gateways), courtyards, halls, chapels, obelisks, and smaller temples. What makes Karnak unique is how long it was built and used. Construction started in the 16th century BC. It began small, but eventually, the main area alone had about twenty temples and chapels. Around 30 pharaohs contributed to the buildings, making it incredibly large and complex. While few features at Karnak are unique on their own, their sheer number and size are amazing.

One of the greatest temples in Egyptian history is the Temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak. Like many other Egyptian temples, it honored the gods and recorded past achievements. Thousands of years of history are shown in inscriptions on its walls and columns. These were often changed or redone by later rulers. The Temple of Amun-Re was built in three sections. The third section was added by pharaohs of the late New Kingdom. Following traditional Egyptian architecture, many parts, like the inner sanctuary, were aligned with the sunset of the summer solstice.

A key feature at the site is the 5,000 square meter (50,000 square foot) hypostyle hall. It was built during the Ramesside period. The hall is supported by about 139 sandstone and mud brick columns. The 12 central columns are 25 meters (82 feet) tall and were once brightly painted.

The Ramesseum

Ramesses II, a pharaoh from the 19th Dynasty, ruled Egypt from about 1279 to 1213 BCE. He achieved many great things, like expanding Egypt's borders. He also built a massive temple called the Ramesseum, near Thebes. Thebes was the capital of the New Kingdom at that time.

The Ramesseum was a magnificent temple. It had huge statues guarding its entrance. The most impressive was a statue of Ramesses himself, originally 19 meters (62 feet) tall and weighing about 1,000 tons. Only the base and torso of this seated pharaoh statue remain. The temple also features impressive carvings. Many show Ramesses' military victories, such as the Battle of Kadesh (around 1274 BCE).

The Ramesseum was built as a place of worship for Ramesses II. Although only traces of its original structure remain, it was more than just a temple. It also included a palace. The Ramesseum had other rooms to serve the people, like bakeries, kitchens, and supply rooms. These were found in the southern part of the temple during an excavation. There was also a school where boys learned to become scribes. This school was located between the kitchen and the palace.

After the Ramesseum fell into ruin, other burials were made there. It was given to certain families of the 22nd dynasty. They used it as a cemetery, placing new burials in the chambers. Many restorations have been done to the Ramesseum. For example, a huge head of Ramesses II was placed on a stand and secured after being found on the ground. Areas made of mud bricks were also restored. Modern bricks, made of the same material but stronger, were used to protect against natural elements like heavy rain.

Temple of Malkata

During the reign of Amenhotep III, workers built over 250 buildings and monuments. One of the most impressive projects was the temple complex of Malkata. Ancient Egyptians called it the "house of rejoicing." It served as his royal home on the west bank of Thebes, south of the Theban burial grounds.

The site covers about 226,000 square meters (2,432,643 square feet). Because of its huge size and many buildings, courts, parade grounds, and homes, it was more than just a temple and royal dwelling. It was like a small town.

The central part of the complex held the Pharaoh's apartments. These had several rooms and courtyards, all arranged around a columned banquet hall. Along with the apartments, which likely housed the royal family and foreign guests, there was a large throne room. This room connected to smaller chambers for storage, waiting, and private meetings. Other important parts of this area included the West Villas, the North Palace and Village, and the Temple.

The temple itself was about 183.5 by 110.5 meters (602 by 363 feet). It had two main parts: a large front courtyard and the temple proper. The large front court was 131.5 by 105.5 meters (431 by 346 feet). It faced east–west and took up the eastern part of the complex. The western part of the court was higher and separated by a low wall. The lower court was almost square, while the upper terrace was rectangular. The upper section was paved with mud bricks. A 4-meter (13-foot) wide entrance led from the lower court to the upper landing. A ramp enclosed by walls connected these two levels. This ramp and entrance were in the center of the temple, facing the same direction as the front court.

The temple proper had three distinct parts: central, north, and south. The central part began with a small rectangular anteroom (6.5 by 3.5 meters or 21 by 11 feet). Many doorframes, including those of the anteroom, had inscriptions like 'given life like Ra forever'. A 12.5 by 14.5 meter (41 by 48 foot) hall followed this room. You entered it through a 3.5 meter (11 foot) wide door in the center of the front wall. Evidence suggests the ceiling of this room had yellow stars on a blue background. Today, the walls show only white plaster over mud. However, many decorative plaster fragments found here suggest the walls were also richly decorated. Six columns, arranged in two rows, supported the ceiling. Only small pieces of the column bases remain, but they suggest the columns were about 2.25 meters (7.4 feet) in diameter. The columns were 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) from the walls, and 1.4 meters (4.6 feet) apart in each row. The space between the two rows was 3 meters (9.8 feet).

A second hall (12.5 by 10 meters or 41 by 33 feet) was accessed through a 3-meter (9.8-foot) door in the back wall of the first hall. This second hall was similar to the first. Its ceiling also seemed to have similar decorations. Four columns, arranged in two rows, supported its ceiling. The space between these rows was 3 meters (9.8 feet). In this second hall, at least one room seemed dedicated to the cult of Maat. This suggests the other three rooms in this area might have also served religious purposes.

The southern part of the temple had two sections: western and southern. The western section had 6 rooms. The southern area was large (19.5 by 17.2 meters or 64 by 56 feet), suggesting it might have been another open courtyard. Blue ceramic tiles with gold edges were found in many of these rooms. The northern part of the temple proper had ten rooms, similar in style to those in the southern part.

The temple itself seems to have been dedicated to the Egyptian god Amun. Many bricks were found with inscriptions like "the temple of Amun in the house of Rejoicing." Overall, the Temple of Malkata shares many features with other New Kingdom cult temples. It had magnificent halls and religious rooms, along with many rooms that looked like storage areas.

Valley of the Kings

During the New Kingdom, pharaohs continued to build grand temples to honor themselves after death. However, they stopped being buried in large, visible monuments like the ancient pyramids. Both Old and Middle Kingdom tombs had been robbed, failing to protect the pharaohs' bodies.

Starting with the Eighteenth Dynasty, pharaohs were instead buried in hidden underground tombs. These were located in the Valley of the Kings near Thebes.

These tombs were carved directly into the rock of the valley slopes. Their exact layouts changed over time. But generally, they had a corridor with several sections leading to a burial chamber. At first, only the burial chamber was decorated. But eventually, the walls of the entire tomb were richly decorated with illustrations and texts.

Greco-Roman Period Architecture

During the Greco-Roman period (332 BC–395 AD), Egypt was ruled first by the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty and then by the Roman Empire. Egyptian architecture changed a lot due to the influence of Greek architecture. Even with new rulers, they respected Egyptian religion. They built many new temples or expanded old ones.

The country's capital moved to the new city of Alexandria on the Mediterranean coast. Its design was mostly Greek, but with some local Egyptian touches. Most of the ancient city is now underwater or beneath the modern city. However, old descriptions tell us it had many great buildings. These included a royal palace, the Musaeum, the Library of Alexandria, and the famous Pharos Lighthouse.

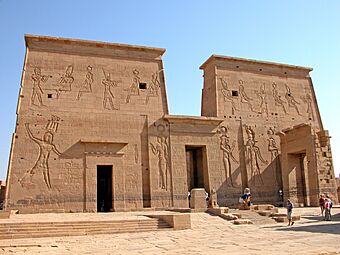

Many well-preserved temples in Upper Egypt come from this time. Examples include the Temple of Edfu, the Temple of Kom Ombo, and the Philae temple complex. While temple architecture stayed mostly Egyptian, new Greek and Roman influences appeared. For instance, you can see new types of column tops called Composite capitals. Egyptian designs also started to appear in wider Greek and Roman architecture.

Much of the burial architecture from this period has not survived. However, some of Alexandria's underground catacombs have been preserved. These were shared by the city's people to bury their dead. They show a mix of architectural styles, combining classical and Egyptian decorations. The Catacombs of Kom El Shoqafa, started in the 1st century AD and expanded until the 3rd century, are a notable example you can visit today.

Ancient Egyptian Fortresses

Ancient Egyptian fortifications were built during times of conflict between different groups. Most fortresses studied from this period were made of similar materials. The only exception was some fortresses from the Old Kingdom, like the fort of Buhen, which used stone for its walls. The main walls were usually made of mud brick but strengthened with other materials like timber. Rocks were also used to protect the walls from erosion and for paving.

Secondary walls were built outside the main fortress walls, quite close to them. This made it hard for invaders, as they had to break through this outer defense first. If an enemy did get past the first barrier, another strategy was used. A ditch was built between the secondary and main walls. This trapped the enemy, leaving them open to arrow fire. During peaceful times, these ditch walls inside fortresses were removed. The materials could then be reused, making the design very practical.

Fortresses in ancient Egypt had many uses. During the Middle Kingdom Period, the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt built fortified stations to control the Nubian Riverside. Egyptian fortresses were not only along the river. Sites in both Egypt and Nubia were placed on rocky or sandy land. This helped spread Egypt's influence and discouraged rival groups from raiding the sites. Inspections of these forts in Nubia found copper smelting materials. This suggests a connection with miners in the region. The presence of these Nubian forts indicates a trade relationship. Miners would collect materials and exchange them at the forts for food and water. Egypt controlled Nubia through these fortresses until the Thirteenth Dynasty.

Pelusium Fortress

The Pelusium fortress protected the Nile Delta from invaders. It served this role for over a thousand years. Pelusium was also a major trade center, both by land and sea. Trade mainly happened between Egypt and the Levant. We don't have exact dates for its founding. However, it's thought Pelusium was built during the Middle Kingdom or during the Saite and Persian periods (8th to 6th century BC). Pelusium was an important part of the Nile region. Other ruins found outside its borders show that the area was widely settled.

Architecturally, Pelusium's structures, like its gates and towers, seem to have been built from limestone. The discovery of copper-ore suggests a metalworking industry was active here. Excavations have also found older materials dating back to early dynasties. These include basalt, granite, diorite, marble, and quartzite. However, these materials might have been brought in more recently. The fortress was built very close to the Nile River. It was largely surrounded by sand dunes and coastlines.

Several reasons led to the decline of the Pelusium fortress. During its existence, events like the Bubonic Plague appeared in the Mediterranean for the first time. Multiple fires also occurred within the fortress. Conquest by the Persians and a decrease in trade might have also led to people leaving the area. Officially, natural events like earthquakes caused Pelusium to fall apart. The site was finally abandoned around the time of the Crusades.

Fortress of Jaffa

Jaffa Fortress was important during the New Kingdom period. It served as both a fortress and a port on the Mediterranean coast. Even today, Jaffa is a main Israeli port. Originally controlled by the Canaanites, the site later came under the Egyptian Empire. During the Late Bronze Age, it was a successful base for the campaigns of 18th dynasty Pharaohs.

The site had many functions. It's believed that Jaffa's main purpose was to store grain for the Egyptian Army.

The Rameses gate, dating to the Late Bronze Age, connects to the fortress. Defensive walls (ramparts) were also found within the fortress. During excavations, many items were discovered. These included bowls, imported jars, pot stands, and evidence of beer and bread. These discoveries highlight the importance of food storage and ceramic making in the area.

Changes and Later Uses

Reuse of Ancient Materials

After Roman rule began, some temples were used for new purposes. The Luxor Temple, for example, became the center of a Roman military camp. Parts of the temple were dedicated to worshipping the divine emperor. The southern part of the temple later became a Christian church. The Mosque of Abu Haggag was added to the east side of the temple during the Islamic period.

Stones and architectural pieces from ancient Egyptian monuments were often reused in later buildings. Many medieval mosques, for instance, include old stone blocks with visible hieroglyphic carvings. From the Roman period until the 1800s, many ancient Egyptian obelisks were also taken and moved to other countries. There, they were often set up again as prized monuments.

Modern Egyptian Revival

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Egyptian architectural designs were used in modern architecture. This led to a style called Egyptian Revival architecture. Later, this style was especially popular for Egyptian Theater cinemas and other themed entertainment places.

See also

- Art of ancient Egypt

- Center for Documentation of Cultural and Natural Heritage

- Coptic architecture

- Egyptian Revival decorative arts

- Urban planning in ancient Egypt

- List of ancient Egyptian sites