Ancient Regime of Spain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ancient Regime of Spain |

|

|---|---|

Symbols used by the institutions during the last years of the Ancien Régime.

|

|

| Date formed | circa 15th century |

| Date dissolved | early 19th century |

The Spanish institutions of the Ancien Régime were the old ways Spain was governed, socially organized, and economically run for a long time. This period, called the Ancien Régime (which means "Old Rule" in French), lasted from the late 1400s with the Catholic Monarchs until the early 1800s. It was a time when Spain had a very strong king, a society divided into different groups (like nobles and commoners), and an economy that was slowly changing.

Studying this time can be tricky because there were many different rules and groups, and they sometimes even clashed! Spain wasn't fully united in the way it is today. The king and his army were a strong unifying force, and so was the Inquisition. Other things, like the way nobles and priests were organized, were similar across different kingdoms. However, some things were very different, like the Cortes (parliaments) or the tax system in Aragon compared to Castile. Even when the Bourbon kings tried to make things more central, some regions like the Basque provinces and Navarre kept their special old laws, called fueros.

Contents

Society in Old Spain

Society in Spain during the Ancien Régime was made up of many different groups. People belonged to their families, villages, or larger areas like provinces or kingdoms. They also belonged to groups based on their jobs, like guilds for craftsmen, or religious groups.

People thought of the kingdom like a human body, with the king as the head and all the different groups as parts of the body. Everyone had their place and rules to follow. These groups were set up in a hierarchy, meaning some were above others. Leaders were expected to protect their people, but also to keep them in their place. What we now call public services were often handled by private individuals or powerful families.

Who Were the Main Groups?

The two main privileged groups were the nobility and the clergy (church leaders).

- The nobility were often wealthy landowners. From the 1500s, many nobles moved to Madrid to be close to the king's court.

- The clergy was a more open group, meaning people from any background could join, though it also had its own ranks and leaders.

The common people were the largest and most varied group. They included everyone from poor farmers to early business owners and educated people working in administration. Some groups, like Judeo-converts (Jews who converted to Christianity), Moriscos (Muslims who converted), and Gypsies, faced discrimination and persecution.

Kings, Nobles, and the Land

The king was at the top of the system. Spanish kings traced their power back to ancient Visigothic rulers or to the Carolingian Empire. Over time, the idea of a king's power being passed down through family became very strong. This allowed kings to treat their kingdoms almost like personal property.

The nobility, who were the warriors and defenders, also had a special place in society. Along with the high clergy, they formed the ruling class, enjoying many privileges.

How the Monarchy Grew Strong

The Trastámara family of kings made the monarchy very powerful. The crisis of the 1300s led to a clear split between the very rich, powerful nobles and the lower nobility (like hidalgos or knights). Many nobles tried to prove their ancient family lines to keep their social standing, even if they weren't rich anymore.

There was also a difference between the north of Spain, where noble families originated but didn't own huge lands, and the south, where military orders and great noble families had vast estates. For common people, being an "Old Christian" (someone whose family had always been Christian) became a source of pride. Laws about "limpieza de sangre" (purity of blood) meant that people with Jewish or Muslim ancestors faced legal discrimination. This continued even after the expulsion of Jews in 1492 and Moriscos in 1609.

The Catholic Monarchs united Spain through marriage (Aragon and Castile) and conquest (Canary Islands, Granada, Navarre, America). When the Habsburg family took over, they added even more lands in Europe. They generally respected local laws, though there were some conflicts, like the Comuneros Revolt.

Historians call this the Hispanic Monarchy because the different kingdoms were united under the same king, but they kept their own laws, languages, money, and institutions. The kings tried to unite the noble families by creating the title of Grandee in 1520, which included a small number of top aristocratic families from both crowns. Marriage between these families was encouraged to create a single elite group across all kingdoms.

Later, the Bourbon family (from France) brought in the idea of absolute monarchy, where the king had total power. This led to a civil war, the War of the Spanish Succession, which changed Spain's government.

-

Íñigo López de Mendoza, Marquis of Santillana (1400s). He was a powerful noble who owned many castles and lands. He was very skilled at politics and helped King John II of Castile when needed, which increased his family's power.

-

Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, Duke of Alba (1500s). He was a great general for Kings Charles V and Philip II. He served as governor in Milan, Naples, and the Netherlands.

-

Saint Francis Borgia (1500s). He was a Duke and a courtier before becoming a Jesuit priest. He was even Viceroy of Catalonia. His life shows how high nobility could also be deeply religious.

-

Carlos Gutiérrez de los Ríos, Duke of Fernán Núñez (late 1700s/early 1800s). He was a diplomat and attended important meetings in Europe. He was the last of his family to rule over his town directly, but his family remained part of the aristocracy.

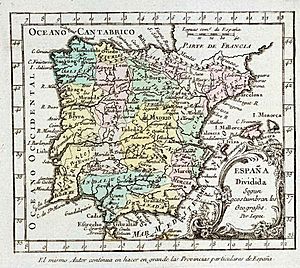

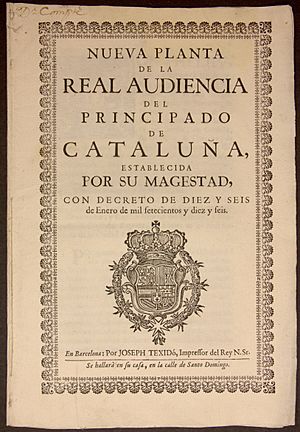

This article mainly focuses on the Spanish kingdoms within the Iberian Peninsula. From the early 1700s, Spain became more unified. This happened after Portugal separated in 1640, and especially after the Nueva Planta decrees (1707-1716). These decrees made the laws of the Crown of Aragon (Catalonia, Valencia, Mallorca, and Aragon) similar to those of Castile.

Local Government, Parliaments, and Money

Local government in Spain was very important. Towns and cities had their own councils, which were very powerful. In the early Middle Ages, all citizens could participate in these councils. But over time, wealthy families took control, and positions in the town council became hereditary. The king also sent a representative, called a corregidor, to oversee the towns.

The Cortes (Parliaments)

The most important towns had a vote in the Cortes, which were like parliaments. These Cortes represented the "kingdom" and had powers to make laws and approve taxes. They were stronger in Aragon, where they had three or four different groups (nobles, clergy, and commoners). In Castile, the privileged groups stopped attending, making the Cortes weaker. They lost even more power in the 1700s.

The Royal Treasury

The treasury was key to how the monarchy worked. Castile provided most of the money, while Aragon, Navarre, and the Basque provinces had special tax exemptions. Taxes were often collected by cities for their own benefit, or by private individuals who leased the right to collect them.

The main sources of income were the "quinto real" (a fifth of American metals) and the "alcabala" (a sales tax). However, these were never enough. The monarchy constantly borrowed money from bankers and issued public debt, leading to frequent financial crises. The tax system was complex and unfair.

The Nueva Planta decrees in the 1700s helped simplify the tax system in Catalonia and Valencia, making it more efficient and boosting economic activity. This new system was seen as a model for the rest of Spain, but it was hard to apply in Castile due to resistance from those who benefited from the old system.

Economic Life in Old Spain

Economic life was only partly controlled by the king. In Aragon, old medieval institutions like the Llotja (stock exchange) and the Consulate of the Sea (for trade) were important for long-distance trade.

Trade with the Americas

When Spain colonized America, controlling trade became vital. The Casa de Contratación in Seville had a monopoly on trade with the Americas. In the 1700s, kings tried to open this monopoly to other Spanish ports to encourage more trade.

Local Crafts and Markets

At a local level, town councils controlled crafts and trade through rules called municipal ordinances. These rules were often managed by guilds, which were associations of workshops for the same trade. Guilds tried to prevent competition, control who could practice a trade, maintain quality, and protect their members' interests.

Large fairs, like those in Medina del Campo, were important for connecting Spanish wool trade with northern Europe's financial markets. However, the opportunities from American trade and the monarchy's huge debt often hurt Spanish businesses, benefiting other European countries instead. Internal customs and different laws in each kingdom also made it hard to create a unified national market.

Farming and Livestock

Most people lived in the countryside and worked in agriculture. Farming methods were traditional. Peasants often lived under a manorial system, where lords had control over their land and lives.

Livestock farming, especially sheep, was very important and often favored over agriculture. The Mesta in Castile and similar groups in Aragon were powerful organizations that protected the interests of sheep farmers. This often led to conflicts between shepherds and farmers.

Enlightenment thinkers in the 1700s criticized these old systems, saying they prevented economic growth. They wanted clearer property rights and free markets. The Sociedades Económicas de Amigos del País (Economic Societies of Friends of the Country) were created to promote new ideas and improvements in agriculture and industry.

Government, Justice, and Laws

The central government used a system of many different Councils, known as the polysynodial system. There were Councils for specific topics like the Treasury or the Inquisition, and for different territories like the Council of Aragon or the Council of Italy. The Council of Castile handled most of Spain's internal affairs, and the Council of State dealt with international relations.

The king also had a special, secret committee called the Chamber of Castile, which advised him on matters of royal favor. Sometimes, the king would rely heavily on a trusted advisor, called a favourite.

Under King Philip V, the old Councils became less important (except for the Council of Castile). New "Secretariats of State and Office" became the main government bodies. These were the early versions of today's government ministries and cabinets.

Secretaries who managed daily affairs were very important. They were often educated people from lower social classes, which allowed them to rise in society. This sometimes caused jealousy among the high nobles.

Justice was handled at different levels. In towns, local officials like regidores and mayors acted as judges and lawmakers. Spain was known for keeping very detailed written records of all administrative acts, which is a treasure trove for historians today. The General Archive of Simancas was created to store these vast amounts of documents.

Royal Courts

For the Crown of Castile, the highest courts were the Reales Audiencias y Cancillerías in Valladolid and Granada. These courts handled legal cases for large regions. Other courts were created later in places like Galicia and Seville.

The Crown of Aragon, the Basque provinces, and Navarre had their own legal systems, which gave less power to the king. These special laws, called fueros, were largely kept even after the Nueva Planta decrees and later conflicts. Today, some of these foral laws still exist, especially in civil law matters.

How Laws Were Made

Laws in Spain came from many different sources. There was a memory of old Visigothic laws, but also local laws (fueros) given to towns to encourage people to settle there. Roman law also influenced Spanish law, giving more power to the king.

Important law collections included the Siete Partidas by Alfonso X the Wise and the Ordenamiento de Alcalá by Alfonso XI. For the American colonies, special laws called the Laws of the Indies were created. These laws were based on Castilian law but adapted for the new territories.

The king's power relied on a permanent, professional army. Unlike older feudal armies that were temporary, this new army was always ready. It was very expensive, but it allowed the king to control nobles and cities. New technologies like artillery made noble castles and city walls less effective as defenses.

The Granada War was a testing ground for this new army, which later became known as the tercios. These elite units gave Spain a big advantage in wars across Europe. The "Spanish Road" (a military route through Europe) allowed Spain to move its troops to defend Catholicism and Habsburg power until the battle of Rocroi.

Protecting the Seas

The old title of Admiral of Castile became honorary. The monarchy took direct control of the navy. Protecting the vast coasts of Spain and its American colonies from other naval powers and piracy was a huge challenge. The Spanish treasure fleet, which brought wealth from America, was remarkably well-protected by galleons. Only one major convoy was captured in hundreds of crossings.

In the Mediterranean, galleys and fortified outposts in North Africa (like Ceuta and Melilla) were used to fight the Ottoman Empire and Berber pirates.

Keeping the Peace

Local officials were in charge of public order. The rollo or pillory was a symbol of their authority, used for public punishments. The Santa Hermandad was a militia (a group of armed citizens) managed by Castilian towns, which the king later controlled. This group helped fight crime, especially in rural areas.

There wasn't a modern police force until the 1800s. Interestingly, the Mossos d'Esquadra in Catalonia, a police force today, started in 1721 to maintain order and fight bandits.

In the 1700s, under the Bourbon kings, the military and civil administration became very closely linked. The intendant was a key figure, combining military and civil authority in the provinces. Spain also rebuilt its navy, creating three main naval bases: Cartagena Naval Base, Cádiz, and Ferrol.

The Royal Artillery School in Segovia was a top scientific institution in the 1700s. It taught mathematics, physics, chemistry, and military engineering, and was a leading center for scientific research and education in Spain.

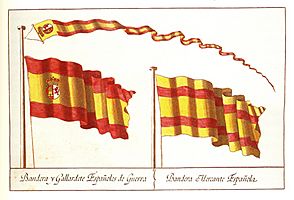

King Charles III introduced important changes. The Marcha Real became the national anthem, and the red and yellow flag became the national flag. He also created new military rules and introduced compulsory military service by drawing lots (the quintas). However, a truly national army, like France's revolutionary army, didn't appear until the Spanish War of Independence.

The Church, Education, and the Inquisition

The Church in Spain was very powerful and closely connected to the king's government. The kings used the Church to maintain social control. The Habsburg kings, like Philip II, were very committed to Catholicism, even saying they would rather lose their kingdoms than rule over heretics.

The king had a lot of influence over the Church in Spain. He could appoint bishops and received a share of church income (the "royal third" of the tithe, which was a very important tax). In the 1700s, the government even started taking some Church properties.

The king's confessor (a priest who heard his confessions) was a very influential figure in the Court. This person often came from a religious order and could influence the king's decisions.

The Church was also a major "pressure group," defending its own interests and exemptions. Many clergy members were educated and held important positions in the government.

The Church was deeply integrated into society. Nobles often made donations to churches and monasteries, and their younger sons and daughters would join religious orders, often bringing large dowries. Church lands were often "mortmain" (meaning they couldn't be sold), until they became national property during the confiscation in the 1800s.

Peasants living on Church lands had similar conditions to those on noble lands. Everyone had to pay religious taxes like tithes. The Church also had its own courts, and churches were considered sacred places where criminals could seek refuge from civil justice.

Religious Orders and Universities

Spain had a network of archdioceses and dioceses, with the Primate See in Toledo. Bishops and canons (priests who served in cathedrals) had great authority. There were also many clerics regular (members of religious orders) living in monasteries and convents.

The quality of the clergy improved over time due to reforms. The Jesuits, founded by Ignatius of Loyola, became very influential.

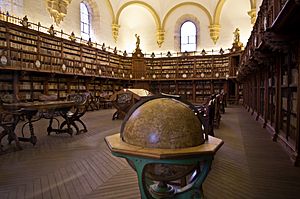

Two important institutions linked to the Church were the Military Orders (like Santiago and Calatrava) and the Universities. Universities like Salamanca, Valladolid, and Alcalá were very important, especially for studying Law and Theology. The "School of Salamanca" was a group of thinkers who shaped the main ideas of Habsburg Spain.

For secondary education, the Jesuits created the Reales Estudios de San Isidro in Madrid, which was a key place for educating the elite. Public education for all children didn't become widespread until much later, in the 1800s.

The Spanish Inquisition

The Spanish Inquisition was a unique institution, perhaps the only one common to all of Spain apart from the king. It was responsible for dealing with religious dissidence. It had courts in important cities and a network of informants called familiares, making it very effective.

The Inquisition and the "limpieza de sangre" (purity of blood) statutes played a big role in shaping the idea of a "Old Christian" and a Spanish national identity during the early Modern Age.

| Preceded by Crisis of the Late Middle Ages |

Ancient Regime of Spain 15th century-19th century |

Succeeded by Enlightenment in Spain |

See Also

In Spanish: Antiguo Régimen de España para niños

In Spanish: Antiguo Régimen de España para niños

- Ancien Régime

Images for kids

-

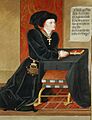

Íñigo López de Mendoza, Marquis of Santillana, by Jorge Inglés. He could cross Spain from North to South sleeping every night in a castle of the wide family network (of Álava origin) of the Mendoza family, which he headed through the House of Infantado. He knew how to maneuver skillfully in the struggles between noble factions, opposing both the privation of Álvaro de Luna and the Infantes of Aragon, supporting King John II of Castile when it was most necessary, which allowed him to significantly increase his own political and territorial power. The Mendozas maintained their prominence in the following reigns, within the so-called humanist, ebolist, romanist or papist faction -opposed to the Albists-.

-

A century later than that of Santillana, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, third Duke of Alba (painted by Titian) belongs to a nobility whose highest aspiration is to figure in the best position in the service of an undisputed monarchy. Outstanding general of Charles V and Philip II, he was governor of Milan (1555), viceroy of Naples (1556) and governor of the Netherlands (1566), where the black legend painted him as a negative stereotype of the Spanish nobleman. Disgraced by a family marital affair, he returned to lead the armies in the Portuguese campaign (1580). The Alba family headed the imperial faction, albista, hispanista or castellanista - opposed to the ebolistas in the 16th century, and the ensenadistas in the 18th century.

-

No lesser lineage possessed the Valencian Saint Francis Borgia, painted by Alonso Cano with the Jesuit habit that he took in his maturity (he became General of the Society of Jesus). He contrasts, but does not deny the way of life of the high nobility: in the century he was Duke of Gandía (Valencian house with Grandeeship) and courtier of Charles V, who took him to his campaigns, married him to a Portuguese aristocrat and appointed him Viceroy of Catalonia. His famous vocation came to him in the truculent burial of Isabella of Portugal ("I will not serve any more Lord that can die").

-

Carlos Gutiérrez de los Ríos, Duke of Fernán Núñez, by Goya. He followed the family tradition of diplomatic service, attending the Congress of Vienna (1814), the swan song of the Europe of the Old Regime where Spain no longer had any relevant role. He was the last of his lineage to exercise jurisdictional dominion over the Cordovan town of his title. Unlike the French Revolution (in which the peasants dispossessed their lords), in Spain this did not mean the loss of property or the ruin of his house, which remains part of the aristocracy to this day.

-

Salón de Cent (for the former Consell de Cent or Consejo de Ciento) of the Barcelona City Council.

-

Pamplona City Hall.

-

Avilés City Hall.

-

Alcañiz City Hall.

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |