Big Runaway facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Big Runaway |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Samuel Hunter | |||||||

The Big Runaway was a huge movement of people in June and July 1778. Settlers living in the frontier areas of north-central Pennsylvania had to quickly leave their homes during the American Revolutionary War.

British supporters, called Loyalists, and Native Americans who were allied with the British, launched a major attack. They destroyed small towns along the northern and western parts of the Susquehanna River. Because of these attacks, local militia leaders ordered everyone to evacuate, meaning to leave for safety.

Most settlers moved to Fort Augusta in what is now Sunbury. This fort was located where the North and West Branches of the Susquehanna River meet. Their abandoned houses and farms were all burned down.

Some settlers came back soon after the first attacks. However, the attacks started again the next year. This led to a second, smaller evacuation known as The Little Runaway. These attacks on the Pennsylvania frontier caused the American army to fight back. They used a "scorched earth" tactic, which meant destroying everything. This included Sullivan's Expedition, which ruined more than 40 Iroquois villages.

Contents

Why the Runaway Happened

In 1768, the Colony of Pennsylvania and the Iroquois Confederacy signed a deal called the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. This treaty changed the border between colonial lands and Iroquois lands. Pennsylvania gained more land in exchange for money and other promises.

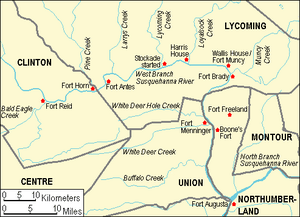

Settlers quickly moved into this new area, called the "New Purchase". More settlements along the West Branch of the Susquehanna River led to the creation of Northumberland County in 1772. These settlements were in areas that are now Northumberland, Union, Lycoming, and Clinton Counties.

The new land stretched as far west as "Tiadaghton Creek." But there was a disagreement about which creek this was. Colonists said it was Pine Creek, which was further west. The Iroquois said it was Lycoming Creek, which was further east. The government agreed with the Iroquois, making Lycoming Creek the border.

Despite this, some settlers built homes west of Lycoming Creek and even west of Pine Creek, near what is now Lock Haven. Since they were outside the colony's official borders, they had no government protection. So, they created their own system of rules, known as the Fair Play system.

When the American Revolutionary War began in 1775, most settlers in this area wanted independence from Great Britain. They supported the Patriot side. About 75 soldiers from the Lycoming County area joined the Continental Army. But soon, the West Branch of the Susquehanna valley became a battleground too.

There had always been some tension between settlers and Native Americans. Attacks became more serious in the winter of 1777–78. Two settlers were killed by Native Americans. Then, two Native Americans were killed by Colonel John Henry Antes and his men. Later, Native American raiders stole goods near Lewisburg. They were stopped near Jersey Shore, and their stolen items were recovered.

British and Iroquois Plans

In 1777, General John Burgoyne of the British army tried to capture the Hudson River. As part of his plan, the British in Quebec recruited many Native Americans. Some of them fought in Burgoyne's campaign.

During the winter of 1777–78, British officer John Butler, Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, and Seneca leaders Cornplanter and Sayenqueraghta made plans for 1778. The Iroquois wanted to launch a "very formidable irruption" (a strong attack) against the frontier. The Seneca leaders especially wanted to target the Susquehanna's west branch. This area gave access to their lands in what is now western New York.

After fighting further south, groups of Seneca, Cayuga, and Lenape warriors began moving into the upper Susquehanna valley.

Attacks Begin

On May 16, 1778, three settlers were killed near Bald Eagle Creek. Over the next four days, three men, seven women, and several children were captured. Later in May, three settler families on Loyalsock Creek were wiped out. Their cabins were burned, two people were killed, and fourteen disappeared, likely captured.

In other incidents in late May, three settlers were taken prisoner near modern Linden. Three Fair Play men were killed trying to get a boat to evacuate their families. Near Lock Haven, a fight wounded one Native American and one Fair Play man.

Local militias (groups of citizen soldiers) had few men, weapons, and supplies. The government of Pennsylvania was busy supplying the main army. They also collected taxes, which were sometimes more than what settlers owned.

Settlers begged for more help, but the government didn't send it right away. As the West Branch Susquehanna valley became a new war zone, the government changed its mind. On May 21, 1778, they promised to send settlers 100 firearms, including 31 rifles. They also sent lead for bullets and gunpowder. They asked General George Washington to send 250 riflemen from the army. However, none of this help arrived in time.

Simple forts and strong houses gave settlers some protection. These included Fort Reed, Fort Horn, Antes Fort, and others. As the danger grew, more settlers moved into these forts. But they were still in danger when they left to tend their farms.

June 10, 1778, was a very bloody day for Lycoming County. There were three separate attacks on settlers. Two attacks were along Loyalsock Creek, and one was near Lycoming Creek. In one event, a group of twelve, including a friendly Native American, went looking for stolen horses. Robert Covenhoven, a guide, joined them. They were ambushed, some were killed, six were captured, and Covenhoven escaped.

Another group of three men went to get cattle. They were ambushed by Native Americans and at least one British supporter. Two settlers were killed, and one was wounded and captured.

Later that day, sixteen settlers on their way to Lycoming Creek were attacked in what is now Williamsport. This was called the "Plum Tree Massacre." Twelve of the sixteen were killed. Two girls were captured, and a boy and a girl escaped. They were so scared they couldn't clearly say what happened. Search parties later found all the victims. It was believed one group of Native Americans and British supporters caused all these attacks.

The Big Evacuation

All these attacks, and the lack of military help, made the settlers along the West Branch of the Susquehanna lose hope. In early summer 1778, news came that a large group of Native American warriors, possibly with British soldiers, was coming to destroy all settlements. A friendly Native American named Job Chiiloway warned Fort Reed (modern Lock Haven). Sadly, he was then murdered by a settler.

The Wyoming Valley battle and massacre happened on July 3, 1778, near Wilkes-Barre. This attack first overwhelmed small settler forts, then led to a massacre. This terrible news caused local leaders to order everyone to leave the entire West Branch valley.

At least two brave riders risked their lives to warn others. Rachel Silverthorn volunteered to leave the safety of Fort Muncy. She rode along Muncy Creek and the Wyalusing Path, warning settlers. They fled to Fort Muncy. Her own family's cabin was later burned.

Robert Covenhoven, who had served under George Washington, also rode west. He warned settlers at Fort Antes and the western part of the valley. Covenhoven was one of the Fair Play Men who signed their own Declaration of Independence.

Most settlers had already gathered at small forts for safety. But now, even the forts and their homes were abandoned. Settlers drove their livestock and floated a few belongings on rafts down the river. Women and children rode on the rafts. Men walked along the river bank to protect them and guide the animals.

Their abandoned property was burned by the attackers. Some settlers reported fleeing at night, seeing the glow of their burning homes behind them.

Fort Horn and all the Fair Play Men settlements were destroyed. In the New Purchase area, only Fort Antes (made of strong oak logs) and the stone Wallis House survived the fires. The property losses were huge. Colonel Samuel Hunter, the commander of Fort Augusta, was criticized for ordering the evacuation. Many felt that military help could have saved the settlements.

What Happened Next

Some settlers returned soon after, even while their homes were still smoking. Many who fled were recent immigrants from New Jersey, escaping the war there. They were not well-prepared for attacks and simply returned to New Jersey.

The Pennsylvania government then sent military aid. Colonel Thomas Hartley built Fort Muncy to protect settlers who came back. On September 24, 1778, he led about 200 men up the Sheshequin Path. They went along Lycoming Creek to the North Branch of the Susquehanna. Their goal was to fight back against the Iroquois.

Hartley's expedition traveled about 300 miles (500 km) in two weeks. They defeated several Iroquois groups and destroyed some Native American villages. This showed that it was possible to fight in Iroquois territory. It also came before the Continental Army's larger expedition the next year.

In summer 1779, General John Sullivan led an expedition. His forces went up the North Branch of the Susquehanna. They destroyed at least forty Native American villages in New York and Pennsylvania. This was part of a "scorched earth" campaign.

The Native Americans knew about Sullivan's plans. They launched their own attack on the West Branch of the Susquehanna. They hoped to distract Sullivan or attack him from behind. Robert Covenhoven, scouting again, discovered their attacking force.

Authorities ordered a second evacuation. So, settlers who had returned had to flee a second time in summer 1779. This was called the "Little Runaway." The second attacking force had about 200 Native Americans and 100 British and Loyalist soldiers.

This time, the evacuation was less panicked. However, Fort Freeland (near Turbotville) did not evacuate. It's unclear if they didn't get the order or ignored it. More than half of the settlers who had fled there were killed. Most of the rest were taken prisoner.

Sullivan's expedition and the harsh winter that followed helped reduce attacks. The area became more stable, encouraging people to resettle. The Little Runaway and Sullivan's Expedition also made the government more committed to protecting the frontier.

Forts and Strongholds

- Fort Augusta - Located where the Susquehanna River branches meet in Northumberland County. This strong fort was the main base for the local soldiers. Settlers fled here during the Big Runaway.

- Boone's Fort - A fortified gristmill (a mill for grinding grain) owned by Hawkins Boone. He was a cousin of Daniel Boone.

- Fort Menninger - Found near White Deer Creek in what is now Union County.

- Fort Freeland - Located in north-central Northumberland County near Turbotville.

- Fort Brady - This was the fortified home of Captain John Brady near Muncy in southern Lycoming County.

- Fort Muncy - The fortified home of Samuel Wallis in Muncy Township, just a few miles from Fort Brady.

- Harris House - A strong, fortified home near Loyalsock Creek in Lycoming County.

- Stockade Started - This stockade (a fence of strong posts) was never finished. It was along Lycoming Creek in the west end of Williamsport.

- Fort Antes - A stockade built around the fortified home of Colonel John Henry Antes. It was in Nippenose Township, south of Jersey Shore.

- Fort Horn - Located at the mouth of Pine Creek in eastern Clinton County.

- Fort Reid - Found at the mouth of Bald Eagle Creek near Lock Haven in Clinton County, Pennsylvania.

Images for kids