Chinatown, Manhattan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Chinatown, Manhattan

曼哈頓華埠 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

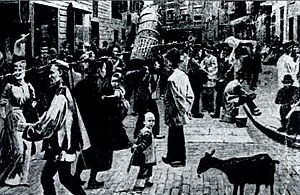

Crossing Canal Street in Chinatown, facing Mott Street toward the south

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Country | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| State | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| City | New York City | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Borough | Manhattan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Community District | Manhattan 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Total | 1.99 km2 (0.768 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population

(2010)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Total | 47,844 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Density | 24,053/km2 (62,300/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Asian | 63.9% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • White | 16.3% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Hispanic | 13.4% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Black | 4.8% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Other | 1.6% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Economics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Median income | $68,657 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ZIP Codes |

10002, 10013

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area code | 212, 332, 646, and 917 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Manhattan's Chinatown is a lively neighborhood in Lower Manhattan, New York City. It is famous for being home to the largest group of Chinese people in the Western Hemisphere. Chinatown is also one of the oldest Chinese communities outside of Asia.

This neighborhood is one of nine Chinatowns in New York City. It is also one of twelve in the larger New York area. This region has the biggest Chinese population outside of Asia, with nearly 900,000 people.

Historically, most people in Manhattan's Chinatown spoke Cantonese. However, in the 1980s and 1990s, many immigrants who spoke Fuzhounese arrived. They created a new area called Little Fuzhou (小福州) in the eastern part of Chinatown. The older, western part is sometimes called Little Hong Kong/Guangdong (小粵港). Today, many people in Chinatown are learning to speak Mandarin Chinese, which is the official language in Mainland China and Taiwan.

While other Chinatowns in New York City, like those in Queens and Brooklyn, have grown larger, Manhattan's Chinatown remains very important. It is a cultural center for Chinese people living outside China. It is home to the Museum of Chinese in America and many Chinese publications.

Chinatown is part of Manhattan Community District 3. Its main ZIP Codes are 10013 and 10002. The New York City Police Department's 5th Precinct patrols the area.

Contents

Exploring Chinatown's Borders

Chinatown does not have official borders. However, people generally agree on its approximate edges:

- Grand Street to the north, where it meets Little Italy.

- Worth Street to the southwest, next to Civic Center.

- East Broadway to the southeast, bordering Two Bridges.

- Allen Street to the east, next to the Lower East Side.

- Lafayette Street to the west, bordering Tribeca.

People and Culture in Chinatown

In 2000, about 66% of Chinatown's 84,840 residents were from Asia. The neighborhood is unique because it is both a place where people live and a place where businesses thrive. Estimates suggest that between 90,000 and 100,000 people live here.

Chinatown's Population Changes

According to the 2010 United States Census, Chinatown had 47,844 residents. This was a decrease from 52,375 people in 2000. The neighborhood covers about 332 acres.

The racial makeup of Chinatown changed between 2000 and 2010. The number of White residents increased, while the number of Asian and Hispanic/Latino residents decreased.

Chinatown is part of Manhattan Community Board 3. This district also includes the East Village and the Lower East Side. Most residents are adults, with many between 25 and 64 years old.

The average household income in Chinatown in 2017 was $68,657. In 2018, about 18% of residents in the wider Community District 3 lived in poverty. This is higher than the average for Manhattan.

Chinese Cultural Traditions

Even with a growing Fuzhou population, many businesses in Chinatown are still owned by Cantonese speakers. The western part of Chinatown, which is mostly Cantonese, remains a busy business area. Because of this, many Fuzhounese people have learned Cantonese for their businesses. This is especially true for large places like Dim Sum restaurants on East Broadway, also known as Little Fuzhou.

Many Fuzhou immigrants who arrived in the 1980s and early 1990s learned Cantonese to find jobs and talk with the Cantonese-speaking community. Some had even lived in Hong Kong and already spoke Cantonese. However, since the 2000s, newer Chinese immigrants mostly speak Mandarin Chinese, which is China's national language.

A key difference between the Cantonese and Fuzhou parts of Chinatown is that the Cantonese area is a big tourist spot. The Fuzhou area, however, focuses more on serving its local community. Streets like Bowery, Chrystie Street, Catherine Street, and Chatham Square mark the general border between these two communities.

Gentrification and Population Shifts

Since the early 2000s, many buildings in Chinatown and nearby areas have been bought by new landlords. These landlords often charge higher rents or tear down buildings to build new ones. This has led to some residents, especially Fuzhouese tenants, facing challenges with housing rules. Long-time Cantonese residents, who often have stable leases, have found it harder for landlords to force them out.

By 2009, many newer Chinese immigrants chose to settle along East Broadway. Also, Mandarin Chinese started to become more common than Cantonese in New York's Chinatown. The Flushing Chinatown in Queens is now seen as a major cultural center for Chinese New Yorkers.

Chinatown as a Shopping Hub

Despite changes, Chinatown remains a popular shopping area for Chinese residents and tourists. Even high-income professionals are moving in and supporting local Chinese businesses. The western part of Chinatown, known as Little Hong Kong/Guangdong, is still very active. However, the eastern part, Little Fuzhou, has become more residential and has seen a decline in businesses.

In 2016, Wing on Wo and Co, Chinatown's oldest continuously running business (since 1890), was almost sold. But a grandchild of the original owner, Mei Lum, decided to take over. She started the "W.O.W. Project" to protect Chinatown's culture through art and community events.

Chinatown's History

Ah Ken and Early Chinese Arrivals

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1990 | 51,439 | — | |

| 2000 | 59,320 | 15.3% | |

| 2010 | 52,613 | −11.3% | |

| Asian American population | |||

Ah Ken is believed to be the first Chinese person to settle permanently in Chinatown. He arrived around the 1840s and started a successful cigar store on Park Row. Other early immigrants also found work as cigar makers or by carrying billboards. Ah Ken might have also run a small boarding house on Mott Street, renting beds to the first Chinese immigrants.

The Chinese Exclusion Era

Because of unfair treatment and new laws on the U.S. West Coast, some Chinese immigrants moved to East Coast cities. They looked for jobs in places like laundries and restaurants. Chinatown began on Mott, Park (now Mosco), Pell, and Doyers Streets. By 1870, about 200 Chinese people lived there. When the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1882, the population grew to 2,000. This law made it very hard for Chinese women to immigrate, so for a long time, there were many more men than women in Chinatown.

Early Chinatown was influenced by Chinese "tongs" or associations. These groups were a mix of family groups, political alliances, and sometimes even criminal groups. They offered help to new immigrants, like loans and business support. These associations formed a larger group called the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association. Sometimes, rival groups had conflicts, especially on Doyers Street.

Columbus Park, the only park in Chinatown, was built on what used to be the center of the famous Five Points neighborhood. This area was known for being a tough immigrant neighborhood in the 1800s.

After Immigration Changes

After the United States changed its immigration laws in 1965, many more immigrants from Asia came to the country. This caused Chinatown's population to grow a lot. The neighborhood expanded, and more families moved in. Before 1965, most people in Manhattan's Chinatown spoke Taishanese. After 1965, many Cantonese speakers from Hong Kong and Guangdong province arrived, and Standard Cantonese became the main language.

During the 1970s and 1980s, more immigrants from Guangdong and Hong Kong helped Chinatown grow north of Canal Street and east of the Bowery. However, until the 1980s, the western part of Chinatown was the busiest Chinese business area. The eastern part, which was once part of the Lower East Side, grew more slowly.

In the 1990s, Chinese people also began moving into parts of the western Lower East Side. This area had previously been home to Eastern European Jews and Hispanics.

Moving to Brooklyn's Chinatown

In the late 1980s and 1990s, many new Fuzhou immigrants came to Manhattan's Chinatown. However, by the 2000s, more Fuzhou immigrants started settling in Brooklyn Chinatown in Sunset Park. This area in Brooklyn is becoming a new "Little Fuzhou" for New York City. This shift has made Brooklyn's Chinatown grow very quickly.

Some landlords in Manhattan were accused of not wanting to rent to Fuzhou immigrants. This was due to worries about rent payments or crowded apartments. As a result, many Fuzhou immigrants rented small spaces from other Fuzhou residents.

While only about 10% of Chinese speakers in Manhattan's Chinatown speak Mandarin as their first language, it is becoming a common second language.

Gentrification in Chinatown

Rising real estate prices and high rents in Manhattan are affecting Chinatown. Many new Chinese immigrants cannot afford the rents. Because of this, most new Chinese immigrants are now moving to other Chinatowns in New York City. These include Flushing and Elmhurst in Queens, and Brooklyn Chinatown and its smaller areas in Brooklyn.

Many apartments that used to be affordable are being renovated and rented for much higher prices. Building owners often end leases for lower-income residents as property values go up.

Since the early 2000s, more buildings in Chinatown have been taken over by new landlords. This has led to challenges for many Fuzhouese tenants, especially in the eastern part of Chinatown. City officials have also been inspecting apartments and addressing issues like overcrowding.

Long-time Cantonese residents in the western part of Chinatown, who often have stable leases, have found it harder for landlords to force them out. However, new landlords continue to look for ways to change leases.

By 2009, many newer Chinese immigrants settled along East Broadway. Also, Mandarin Chinese started to become more common than Cantonese in New York's Chinatown. The Flushing Chinatown in Queens is now seen as a major cultural center for Chinese New Yorkers.

Chinatown's Look and Feel

Neighborhoods within Chinatown

Little Fuzhou (小福州)

From the late 1980s to the 1990s, many Fuzhou immigrants arrived in New York City. They mostly settled in Manhattan's Chinatown and later in Brooklyn's Chinatown. Because many had no legal status and faced difficulties finding jobs, Manhattan's Chinatown was the only place they could find affordable housing and be among other Chinese people.

Since Fuzhou immigrants had different cultural and language backgrounds from Cantonese people, they settled in the eastern part of Chinatown. This area was still a mix of Chinese, Hispanic, and Jewish residents. They created their own Fuzhou community along East Broadway and Eldridge Street. East Broadway became known as Fuzhou Street No. 1.

In the early 2000s, rising costs in Manhattan's Chinatown caused the Fuzhou population to shift to Brooklyn's Chinatown. Brooklyn became the most affordable Chinese area in New York City. Brooklyn's Chinatown is now becoming the main center for Fuzhou culture in New York City.

The Fuzhou immigrants helped keep the Chinese population strong in Chinatown. They also played a role in property values increasing quickly in the 1990s.

Little Hong Kong (小香港) / Little Guangdong (小廣東)

Even though many Fuzhou immigrants moved to Brooklyn, Manhattan's Cantonese population is still strong. The western part of Chinatown remains a central place for Cantonese people to shop, work, and socialize.

The term Little Hong Kong (小香港) was once used to describe Manhattan's Chinatown when many immigrants from Hong Kong arrived. A more fitting name might be Little Guangdong (小廣東) or Cantonese Town (廣東埠). This is because Cantonese immigrants come from different parts of the Guangdong province in China. This long-established Cantonese community, also known as the Old Chinatown of Manhattan, is found along Mott, Pell, Doyer, Bayard, Elizabeth, Mulberry, Canal, and Bowery Streets.

Newer Cantonese communities have also started in parts of Bensonhurst and Sheepshead Bay/Homecrest in Brooklyn.

Fuzhouese and Cantonese Relations

The Fuzhou immigration pattern in the 1970s was similar to the Cantonese immigration in the late 1800s. Mostly men arrived first, then brought their families later. When Fuzhou immigrants arrived in the 1980s and 1990s, Chinatown was mostly Cantonese. Because many Fuzhou immigrants had no legal status and could not speak Cantonese, they faced challenges finding jobs. There was some tension between Cantonese and Fuzhou immigrants.

Chinese Cultural Standards Today

Despite the large Fuzhou population, many Chinese businesses in Chinatown are still owned by Cantonese speakers. Cantonese culture remains strong, especially with many Cantonese-speaking customers visiting on weekends. Even though Mandarin Chinese is becoming more common, Cantonese still has a big influence on Chinatown's culture and economy. The western part of Chinatown, which is mostly Cantonese, is still the main business area.

Many Fuzhou people have learned Cantonese to help their businesses and serve more customers. This is especially true for large businesses like Dim Sum restaurants in Little Fuzhou on East Broadway. Fuzhou immigrants who learned Cantonese make up most of the non-native Cantonese speakers in New York City. However, in recent years, Mandarin Chinese is quickly becoming the most spoken language among new Chinese immigrants.

The Cantonese part of Chinatown is a popular tourist spot, serving both Chinese customers and visitors. The Fuzhou part of Chinatown focuses more on its local community, though it is slowly attracting more tourists. Bowery, Chrystie Street, Catherine Street, and Chatham Square mark the general border between these two communities.

Other Chinatowns in New York City

For a long time, Manhattan's Chinatown had the largest concentration of Chinese people in New York City. However, in recent years, Chinese populations in other parts of New York City have grown much larger.

Other Chinese communities have developed in:

- Flushing in Queens, especially along Roosevelt Avenue to Main Street.

- Sunset Park in Brooklyn, along 8th Avenue.

- Elmhurst and Corona, Queens (which are connected).

- Avenue U in Brooklyn's Homecrest section.

- Bensonhurst, also in Brooklyn.

Outside New York City, growing Chinese communities are appearing in places like Edison, New Jersey and Nassau County, Long Island.

The Flushing Chinatown grew with many Chinese people leaving Hong Kong before 1997 and Taiwanese immigrants. The Brooklyn Chinatown was first settled by Cantonese immigrants but is now mostly home to Fujianese immigrants.

Buildings and Landmarks

Many buildings in Chinatown are old tenement buildings, some over 100 years old. It is still common for these buildings to have shared bathrooms in the hallways. In 1976, Confucius Plaza, a 44-story apartment building, was completed. It provided much-needed housing for thousands of residents and also included a public school, P.S. 124. This building is also a cultural landmark and home to the Asian Americans for Equality (AAFE) organization.

For a long time, Chinatown did not have many special buildings to show visitors they had arrived. In 1962, the Lieutenant Benjamin Ralph Kimlau Memorial archway was built at Chatham Square to honor Chinese-Americans who died in World War II. A statue of Lin Zexu, a Chinese official who fought against the opium trade, is also in the square. In the 1970s, phone booths started to have pagoda-like decorations. In 1976, the statue of Confucius in front of Confucius Plaza became a popular meeting spot. In the 1980s, banks began to use traditional Chinese styles for their buildings. The Church of the Transfiguration, a historic site built in 1815, is near Mott Street. The Museum of Chinese in America has been documenting the Chinese American experience in Chinatown since 1980.

In 2010, Chinatown and Little Italy were recognized as a single historic district on the National Register of Historic Places.

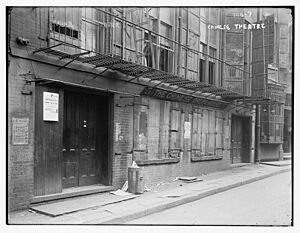

Old Chinese Theaters

In the past, Chinatown had Chinese movie theaters. The first Chinese-language theater was on Doyers Street from 1893 to 1911. Other theaters included the Sun Sing Theater, the Pagoda Theater, the Governor Theater, the Rosemary Theater, and the Music Palace. These theaters showed movies with Chinese and English subtitles. They have all closed now because people can watch movies at home with videotapes, DVDs, and VCDs. Also, Chinese cable channels, karaoke bars, and casinos offer other entertainment options.

Getting Around Chinatown

Two New York City Subway stations are directly in the neighborhood: Grand Street and Canal Street. Other stations are also nearby. New York City Bus routes like the M9, M15, M22, M55, and M103 serve the area.

The Manhattan Bridge connects Chinatown to Downtown Brooklyn. The FDR Drive runs along the East River, with a walking and biking path called the East River Greenway.

The main cultural streets are Mott Street and East Broadway. Busy traffic streets include Canal Street, Allen Street, Delancey Street, Grand Street, East Broadway, and Bowery. There are also several bike lanes in the area.

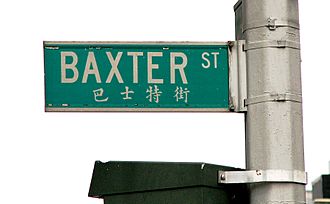

Chinese Street Names

Streets in Chinatown also have Chinese names on bilingual street signs. Before the 1960s, people used informal Chinese names for streets. The first official bilingual signs were put on police call boxes in 1966. In 1969, 44 more signs were installed, showing English names with smaller Chinese names below. These Chinese names matched how streets were pronounced in Taishanese and Cantonese, which were the most common Chinese languages in Chinatown at the time.

In the early 1980s, the program expanded. The new street names were suggested by members of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association. A calligrapher named Tan Bingzhong wrote the Chinese characters by hand for 40 streets.

While there were once 155 bilingual street signs, only 101 remained in 2022. Many damaged signs were replaced with English-only signs or not replaced at all. This is because translated street names are not part of official traffic sign rules. Many people involved in the original program have passed away, and the Chinese population in the area has changed over time.

| Street | Traditional Chinese | Pinyin | Jyutping |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allen Street | 亞倫街 | yǎ lún jiē | ngaa3 leon4 gaai1 |

| Baxter Street | 巴士特街 | bā shì tè jiē | baa1 si6 dak6 gaai1 |

| Bayard Street | 擺也街 | bǎi yě jiē | baai2 jaa5 gaai1 |

| Bowery | 包厘街 | bāo lí jiē | baau1 lei4 gaai1 |

| Broadway | 百老匯大道 | bǎilǎohuì dàdào | baak3 lou5 wui6 daai6 dou6 |

| Broome Street | 布隆街 | bù lóng jiē | bou3 lung4 gaai1 |

| Canal Street | 堅尼街 | jiān ní jiē | gin1 nei4 gaai1 |

| Catherine Street | 加薩林街 | jiā sà lín jiē | gaa1 saat3 lam4 gaai1 |

| Centre Street | 中央街 | zhōngyāng jiē | zung1 joeng1 gaai1 |

| Chambers Street | 錢伯斯街 | qián bó sī jiē | cin2 baak3 si1 gaai1 |

| Chatham Square | 且林士果 | qiě línshìguǒ | ce2 lam4 si6 gwo2 |

| Cherry Street | 車厘街 | Chē lí jiē | ce1 lei4 gaai1 |

| Chrystie Street | 企李士提街 | qǐ lǐ shì tí jiē | kei5 lei5 si6 tai4 gaai1 |

| Delancey Street | 地蘭西街 | de lán xī jiē | dei6 laan4 sai1 gaai1 |

| Division Street | 地威臣街 | de wēi chén jiē | dei6 wai1 san4 gaai1 |

| Doyers Street | 宰也街 | zǎi yě jiē | zoi2 jaa5 gaai1 |

| East Broadway (Little Fuzhou) |

東百老匯 (小福州) |

dōng bǎilǎohuì

(xiǎo fúzhōu) |

dung1 baak3 lou5 wui6

(siu2 fuk1 zau1) |

| Eldridge Street | 愛烈治街 | ài liè zhì jiē | ngoi3 lit6 zi6 gaai1 |

| Elizabeth Street (Private Danny Chen Way) |

伊利莎白街 (陳宇暉路) |

yīlì shā bái jiē

(chén yǔ huī lù) |

ji1 lei6 saa1 baak6 gaai1

(can4 jyu5 fai1 lou6) |

| Forsyth Street | 科西街 | kē xī jiē | fo1 sai1 gaai1 |

| Grand Street | 格蘭街 | gé lán jiē | gaak3 laan4 gaai1 |

| Henry Street | 顯利街 | xiǎn lì jiē | hin2 lei6 gaai1 |

| Hester Street | 喜士打街 | xǐ shì dǎ jiē | hei2 si6 daa2 gaai1 |

| Ludlow Street | 拉德洛街 | lā dé luò jiē | laai1 dak1 lok6 gaai1 |

| Madison Street | 麥地遜街 | mài dì xùn jiē | mak6 dei6 seon3 gaai1 |

| Market Street | 市場街 | shìchǎng jiē | si5 coeng4 gaai1 |

| Monroe Street | 門羅街 | mén luó jiē | mun4 lo4 gaai1 |

| Mosco Street | 莫斯科街 | mòsīkē jiē | mok6 si1 fo1 gaai1 |

| Mott Street (Little Hong Kong/Little Guangdong) |

勿街 (小香港)/(小廣東) |

wù jiē

(xiǎo xiānggǎng) (xiǎo guǎngdōng) |

mat6 gaai1

(siu2 hoeng1 gong2) (siu2 gwong2 dung1) |

| Mulberry Street | 摩比利街 | mó bǐ lì jiē | mo1 bei2 lei6 gaai1 |

| Orchard Street | 柯察街 | kē chá jiē | o1 caat3 gaai1 |

| Park Row | 柏路 | bǎi lù | paak3 lou6 |

| Pell Street | 披露街 | pīlù jiē | pei1 lou6 gaai1 |

| Pike Street | 派街 | pài jiē | paai3 gaai1 |

| Rutgers Street | 羅格斯街 | Luó gé sī jiē | lo4 gaak3 si1 gaai1 |

| Water Street | 水街 | shuǐ jiē | seoi2 gaai1 |

| Worth Street | 窩夫街 | wō fū jiē | wo1 fu1 gaai1 |

| White Street | 白街 | bái jiē | baak6 gaai1 |

| South Street | 南街 | nán jiē | naam4 gaai1 |

Chinatown's Economy

You can find Chinese greengrocers and fishmongers around Mott Street, Mulberry Street, Canal Street, and East Broadway. The Chinese jewelers' district is on Canal Street. Many Asian and American banks are also in the neighborhood. Canal Street, west of Broadway, is known for street vendors selling fake brands of perfumes, watches, and handbags.

Tourism and restaurants are very important to Chinatown's economy. The area has many historical and cultural spots. Tour companies often visit landmarks like the Church of the Transfiguration and the Lin Zexu and Confucius statues. Over 300 Chinese restaurants in Chinatown provide jobs. Some well-known restaurants include Joe's Shanghai, Jing Fong, New Green Bo, and Amazing 66.

Factories also contribute to the economy. Some garment work still happens here, focusing on small, quick orders. Much of the population growth is due to new immigrants.

The September 11, 2001 attacks hurt businesses and restaurants in Chinatown because it was so close to Ground Zero. It took a while for tourism and business to return. However, the area's economy has since recovered. A Chinatown business improvement district was created in 2011 to help local businesses.

The neighborhood has several large Chinese supermarkets. New York Supermarket and Hong Kong Supermarket are two of the biggest. Many Chinese restaurant menus in the U.S. are printed in Manhattan's Chinatown.

Chinatown used to have many mini malls with small shops, but this trend is changing due to rising costs. However, two well-known mini malls still exist: Elizabeth Center on Elizabeth Street and East Broadway Mall on East Broadway. Elizabeth Center is a Hong Kong-style shopping center, popular with Cantonese speakers and tourists. East Broadway Mall, located in the Fuzhou area, mostly serves Fuzhou-speaking customers. It used to be known for employment agencies and bus stations for workers.

East Broadway Mall has seen a decline in businesses due to rising property values and the Covid-19 Pandemic. Elizabeth Center has done better, keeping most of its shops open. In late 2021, the New York State Government gave $20 million to help revitalize areas like Chatham Square and East Broadway Mall. There are plans to turn East Broadway Mall into a cultural community theater.

Learning and Libraries

Chinatown and the Lower East Side have many residents with college degrees. About 48% of adults aged 25 and older have a college education or higher.

Students in Chinatown and the Lower East Side generally do well in school. The percentage of elementary school students who missed many days of school is lower than the city average. Also, 77% of high school students graduate on time, which is higher than the city average.

Schools in Chinatown

Students in Chinatown attend schools run by the New York City Department of Education. P.S. 124, The Yung Wing School, is in Chinatown. It is named after Yung Wing, the first Chinese person to study at Yale University. P.S. 130 Hernando De Soto is also in Chinatown. P.S. 184 Shuang Wen School, a bilingual Chinese-English school, is nearby.

Chinatown's Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) has a branch called Chatham Square at 33 East Broadway. This library opened in 1899, and its current building opened in 1903. It has a large collection of Chinese books, which has been there since 1911.

Images for kids

-

Little Fuzhou (on East Broadway) is seen from the Manhattan Bridge.

See also

In Spanish: Chinatown (Manhattan) para niños

In Spanish: Chinatown (Manhattan) para niños