Florissant Formation facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Florissant FormationStratigraphic range: Late Eocene, 37.2–33.9Ma |

|

|---|---|

Florissant Formation at the Clare fossil quarry in Florissant, Colorado

|

|

| Type | Formation |

| Overlies | Wall Mountain Tuff, Pikes Peak Granite |

| Thickness | 74 m (243 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Shale |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 38°54′50″N 105°17′13″W / 38.914°N 105.287°W |

| Region | Colorado |

| Country | United States |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Florissant, Colorado |

| Named by | Cross |

| Year defined | 1894 |

| Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN Category V (Protected Landscape/Seascape)

|

|

The Pioneer House, showing how the original pioneers of the west lived

|

|

| Location | Teller County, Colorado, United States |

| Nearest city | Florissant, Colorado |

| Area | 5,998 acres (24.27 km2) |

| Authorized | August 20, 1969 |

| Visitors | 71,763 (in 2017) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument |

The Florissant Formation is a special layer of rock found near Florissant, Colorado. It's famous for having tons of incredibly well-preserved fossils of insects and plants. These fossils are found in soft rocks called mudstones and shales.

Scientists have used special dating methods to figure out that these rocks are about 34 million years old. This means they formed during a time called the Eocene epoch. Back then, this area was a big lake!

The fossils are so well-preserved because of a cool natural process. Nearby volcanoes erupted, sending ash into the air. This ash mixed with tiny lake creatures called diatoms, causing them to multiply rapidly. When these diatoms died, they sank to the bottom, covering any dead plants or animals. This created thin layers of clay, mud, and ash, forming "paper shales" that protected the fossils perfectly.

Today, the Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument protects this amazing area. It's a national monument where people can visit, learn, and scientists can continue to study these ancient treasures.

Contents

Discovering the Past: A History of Florissant

The name "Florissant" comes from a French word meaning "flowering." In the late 1800s, people started visiting this area. They were amazed by the wildlife and began collecting fossils and samples. Sadly, many large pieces of petrified wood (fossilized wood) were taken by collectors from what is now called the Petrified Forest.

During the 1860s and 1870s, geologists began to map the area. Scientists from the Hayden Survey explored Florissant in the early 1870s. They studied the fossil plants, insects, and even some animal bones found there. The rock layers were first officially named the Florissant Lake Beds in 1894 by a geologist named Charles Whitman Cross.

In 1969, after a long discussion between local landowners and the government, the Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument was created. This protected the area for future generations. Today, about 60,000 people visit the park each year, and scientists are still making new discoveries. In 2001, the name of the rock layers was updated to the Florissant Formation to match modern geological rules.

Earth's Story: The Geology of Florissant

About 34 million years ago, during the late Eocene and early Oligocene periods, the Florissant area was a lake surrounded by giant redwood trees. The very oldest rocks underneath are called the Pikes Peak Granite, which formed in the Proterozoic era.

There's a big gap in the rock record between the Pikes Peak Granite and the next layer, the Wall Mountain Tuff. This gap happened because of a lot of erosion during the time the Rocky Mountains were forming, an event called the Laramide Orogeny. The Wall Mountain Tuff itself was laid down by a huge volcanic eruption from a far-off caldera (a large volcanic crater).

The Florissant Formation is made up of different layers of rock, including shale, mudstone, and volcanic ash. Scientists have identified six main layers within the formation. These include lower, middle, and upper shale units (which formed in the lake), and mudstone, conglomerate, and pumice units (which formed from volcanic activity or streams).

The shale layers are very thin and full of fossils, showing us what the lake environment was like. The mudstone layers suggest there were also streams and lahars (mudflows from volcanoes) in the area. These lahars might have even blocked valleys, creating the lakes where the shale layers formed.

Volcanic eruptions from the southwest played a huge role in creating the Florissant fossils. Ash and other volcanic material settled in the area. This volcanic material was key to preserving the plants and animals that lived there.

Most of the rocks that formed after the Oligocene and before the Pleistocene have worn away. Some younger layers contain bones of ancient mammoths, dating back about 50,000 years.

Volcanoes of the Past: Thirtynine Mile Volcanic Field

About 25 to 30 kilometers (15-18 miles) southwest of Florissant, there used to be a group of large volcanoes, similar to modern volcanoes like Mount St. Helens. This area was called the Guffey volcanic center, part of the larger Thirtynine Mile volcanic field. These volcanoes erupted often, sending out lava, ash, and mudflows.

The ash from these eruptions created the tuff layers, and the mudflows formed the mudstones and conglomerates in the Florissant Formation. One of these mudflows likely blocked a valley, creating the large lake where many of the fossils were preserved. This ancient lake grew to be as big as 36 square kilometers (14 square miles). There were actually two main periods when the lake existed, creating different fossil-rich layers.

Eventually, these volcanoes became quiet and slowly eroded away. Today, you can't see the volcanoes themselves, but the ancient land surface from the Eocene period is a reminder of their powerful past.

Treasures from Time: Florissant Fossils

The volcanic material that caused so much change also led to the amazing preservation of fossils in Florissant's shales and mudstones. When ash fell on the land, water carried it into streams and lahars, which then flowed into the lake.

These lahars covered the bases of the redwood trees growing at the time. Over millions of years, the tree trunks turned into petrified wood. This happened through a process called permineralization. Minerals from groundwater seeped into the wood, slowly replacing the original tree material with hard, stony minerals like silica. This is how the giant petrified stumps were formed.

Inside the lake, volcanic ash kept falling or washing in. This ash was full of silica. Tiny diatoms in the lake, which also have silica shells, loved this. They would "bloom," meaning their population would explode. At the same time, the stress from the volcanic activity often caused many plants and animals to die. Their leaves and bodies would fall into the lake and get covered by the layers of diatoms and ash.

This process likely happened every year, creating thin layers of ash and clay called "couplets." These layers were pressed down over time to form "paper shales," which are usually less than a millimeter thick. These paper shales hold the most beautifully preserved fossils. Scientists estimate the lake might have lasted for 2,500 to 5,000 years, based on these annual layers.

Ancient Plants: Paleoflora of Florissant

The Florissant Formation has a huge variety of plant fossils, from massive redwood stumps to tiny pollen grains. The Petrified Forest is a major attraction, with about 30 preserved stumps, some of the largest in the world. Most of these stumps are from Sequoia affinis, a close relative of today's coast redwood. These trees could have grown as tall as 60 meters (200 feet) before lahars buried their roots and killed them.

By studying the tree rings, scientists believe these trees were 500 to 700 years old when they died. Some stumps even belong to angiosperms (flowering plants).

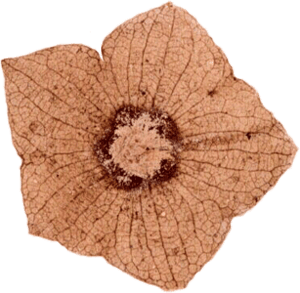

Florissant is also famous for its fossilized leaves, fruits, seeds, cones, and flowers, all perfectly preserved in the paper shales. Most of these come from trees and shrubs. While flowering plants are the most common, there are also conifers (like the sequoias).

Fossilized sequoia cones, leaves, and pollen show some differences from modern California redwoods. The ancient leaves were thinner, and the female cones were smaller.

Scientists have found over 130 different types of pollen in the shale beds. This tells us about many different plant habitats that existed around the lake and further up the valley.

Tiny diatoms, a type of algae with silica shells, are also very common fossils. Their silica shells made them easy to fossilize. When volcanic ash brought more silica into the lake, diatoms would bloom, creating thick mats that helped preserve other fossils. Florissant is important because it shows some of the earliest known freshwater diatoms.

Ancient Animals: Fauna of Florissant

Most of the animal fossils found at Florissant are invertebrates (animals without backbones), but scientists have also found many vertebrates (animals with backbones). The large number of species shows that the environment was perfect for many different animals to thrive. The amazing preservation even gives clues about their behavior!

Tiny Creatures: Invertebrate Life Cycle

The invertebrate fossils include arthropods like spiders, millipedes, insects, and ostracods (tiny crustaceans). There are also mollusks like clams and snails. Spiders and insects are especially important, with over 1,500 species identified!

Many different kinds of arachnids (spiders and their relatives) are found, mostly spiders. Scientists have also found possible harvestmen (daddy long-legs). Interestingly, the fossil spiders are often found with their legs stretched out, not curled up. This might mean they died in warm or acidic water.

The ash-clay beds are full of diverse insects. Mayflies, dragonflies, grasshoppers, beetles, flies, mosquitoes, butterflies, moths, wasps, bees, and ants are just some examples. Beetles are the most common, making up about 38% of all insect fossils. These fossils include both aquatic (water-dwelling) and terrestrial (land-dwelling) insects, giving us a great picture of the ancient ecosystem.

Ostracods likely ate algae at the bottom of the lake. Their hard shells are often preserved. Only one species of ostracod has been fully described so far. Several freshwater mollusks, especially gastropods (snails), have also been found.

Backboned Animals: Vertebrate Life Cycle

Most vertebrate fossils at Florissant are small, broken bone fragments. However, scientists have identified a few species, mainly fish, but also some birds and mammals.

Fish found here include bowfins, suckerfish, catfishes, and pirate perches. Many of these fish lived on the lake bottom and could handle poor water conditions. The fact that most fish are found in specific shale layers suggests that some periods were better for fish than others.

Three types of birds have been found, including a cuckoo. Even though most of the skeletons are missing, enough features remained to identify them. There are also examples of rollers and shorebirds.

Mammals are very rare in the shales. Only one small opossum fossil has been found there. However, in the lower mudstone layers, scientists have found broken bones from a small horse (about the size of a medium dog), a brontothere (an elephant-sized animal with horns), and an oreodont (an extinct animal similar to sheep or pigs). In total, about a dozen different types of mammals have been identified from Florissant, mostly from teeth.

Surprisingly, no reptiles or amphibians have been found at Florissant, even though they would have been expected in such an environment. Scientists aren't sure why, especially since nearly 40,000 specimens have been collected. The water's toxicity from volcanic activity might be a reason, but other aquatic animals did live in the lake.

Ancient Weather: Paleoclimate of Florissant

Fossil plants, especially their leaves, are excellent clues about the ancient climate at Florissant. Plants are very sensitive to changes in temperature and rainfall, while many animals can move to find better conditions.

By comparing fossil plants and leaves to modern plants, scientists can guess what the climate was like. Looking at the overall appearance of the leaves (their "physiognomy") suggests the average temperature was around 13°C (55°F). This is much warmer than Florissant's modern average of 4°C (39°F). Other estimates, based on comparing fossils to their closest living relatives, suggest temperatures between 16°C and 18°C (61-64°F). It also seems that the seasons weren't as extreme as they are today.

Based on the size and features of fossilized teeth, scientists estimate that rainfall during the late Eocene to early Oligocene was about 50-80 centimeters (20-31 inches) per year, with a clear dry season. This is much wetter than the modern average of 38 centimeters (15 inches). Most rain likely fell in late spring to early summer, with rare snow in winter.

Studies of tree rings from the petrified redwoods show that the climate was even better for redwoods than the climate in California today. The average growth rings are wider than those of modern redwoods.

Towards the end of the Eocene, global temperatures started to drop. However, the fossil record at Florissant doesn't clearly show this global cooling trend.

Ancient Homes: Paleohabitats of Florissant

The fossilized algae and water plants tell us that the ancient lake was shallow and filled with freshwater. Near the streams and lake shore, there was plenty of moisture, allowing lush plants to grow. However, further up the hillsides, the plants were more adapted to dry conditions.

At the bottom of the valley, large trees like sequoias dominated the landscape. Smaller trees and shrubs grew beneath them. There was a gradual change in habitats from the wet valley floor up to the drier hillsides, with some areas blending together.

The insects found also point to different habitats. Aquatic insects, like dragonflies, spent their whole lives in or near the lake. Bees and butterflies, on the other hand, preferred the more open spaces in the surrounding hills and meadows.

How High Was It? Paleoaltitude of Florissant

Early guesses about Florissant's elevation during the Eocene were between 300 and 900 meters (1,000-3,000 feet). This is much lower than its modern elevation of 2,500-2,600 meters (8,200-8,500 feet). However, more recent studies using fossil plants suggest the elevation was much higher, possibly between 1,900 and 4,100 meters (6,200-13,500 feet). This would mean that global climate change, rather than the land rising, caused most of the environmental changes.

Scientists are still working to figure out the exact elevation of the Florissant area during the Eocene. While many studies suggest it was higher than previously thought, some evidence still points to a lower elevation.

See also

- Cherokee Ranch petrified forest, another petrified forest in Colorado

- Green River Formation, a similar fossil-rich freshwater formation from the Eocene in the Rocky Mountains.

- Vim Wright

- List of national monuments of the United States

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |