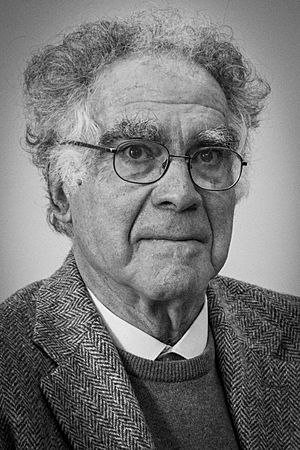

Georges Dumézil facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Georges Dumézil

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 4 March 1898 Paris, France

|

| Died | 11 October 1986 (aged 88) Paris, France

|

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater |

|

| Occupation | Philologist, linguist, religious studies scholar |

|

Notable work

|

Mythe et epopee (1968–1973) |

| Spouse(s) |

Madeleine Legrand

(after 1925) |

| Children | 2 |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Le festin d'immortalité (1924) |

| Doctoral advisor | Antoine Meillet |

| Other academic advisors | Michel Bréal |

| Influences |

|

| Influenced |

|

Georges Edmond Raoul Dumézil (born March 4, 1898 – died October 11, 1986) was a French scholar. He studied languages and myths. He was known for his work in comparative linguistics and comparative mythology. This means he compared languages and myths from different cultures.

Dumézil taught at important universities like Istanbul University and the Collège de France. He was also a member of the Académie française, a famous French institution. He is most famous for his idea called the trifunctional hypothesis. This idea suggests that ancient Indo-European societies and their myths were organized around three main groups or functions. His work greatly influenced how people study myths and ancient European cultures.

Contents

Georges Dumézil's Early Life and Studies

Georges Dumézil was born in Paris, France, on March 4, 1898. His father was a general in the French Army. Georges had a very good education in Paris. He went to schools like Lycée Louis-le-Grand.

He learned Ancient Greek and Latin when he was young. A friend's grandfather, Michel Bréal, inspired him. Bréal was a student of Franz Bopp, a famous linguist. Dumézil then learned Sanskrit, an ancient Indian language. He became very interested in Indo-European mythology and Indo-European religion.

He started studying at the École normale supérieure (ENS) in 1916. During World War I, he served in the French Army. He was an artillery officer and received a medal called the Croix de Guerre. His father was also a high-ranking officer in the artillery.

Dumézil returned to ENS in 1919. His most important teacher was Antoine Meillet. Meillet taught him a lot about Indo-Iranian languages and Indo-European linguistics. Dumézil was more interested in myths than just languages. In the 1800s, scholars like Max Müller studied comparative mythology. But their ideas were later found to be incorrect. Dumézil wanted to bring this field back to life.

In 1920, Dumézil lectured at Lycee de Beauvais. He also taught French at the University of Warsaw in Poland. While in Warsaw, he noticed something interesting. There were similarities between ancient Indian stories (from Sanskrit literature) and the works of the Roman poet Ovid. This made him think that these stories came from a common ancient European background.

Dumézil's PhD and Early Career

Dumézil earned his PhD in comparative religion in 1924. His main paper was called Le festin d'immortalité (The Feast of Immortality). In this paper, he looked at special drinks used in ancient religions. These included Indo-Iranian, Germanic, Celtic, and Slavic traditions.

His early work was also inspired by James George Frazer. Frazer was famous for his studies on myths and rituals. Dumézil's PhD paper was highly praised by his teacher, Meillet. However, other scholars, Marcel Mauss and Henri Hubert, did not support him. They were followers of Émile Durkheim, a famous sociologist. They were also very political. Dumézil had avoided their lectures. This disagreement led to Dumézil losing support from Meillet. Meillet told him it would be hard to get a job in France. He suggested Dumézil go abroad.

Years in Istanbul and Uppsala

From 1925 to 1931, Dumézil was a professor at Istanbul University in Turkey. During this time, he learned Armenian and Ossetian. He also learned other languages spoken in the Caucasus region. This helped him study the Nart saga, a collection of ancient stories. He published important books about these stories.

Dumézil became very interested in the Ossetians and their mythology. This knowledge was very important for his future research. He visited Istanbul every year to study among the Ossetians in Turkey. He also published Le problème des centaures (1929). This book looked at similarities between Greek and Indo-Iranian myths. These early works were part of what he called his "Ambrosia cycle."

His time in Istanbul was very important for his work. He later said these were the happiest years of his life. In 1930, he published La préhistoire indo-iranienne des castes. In this work, he suggested that ancient Indo-Iranians had a caste system. This system existed even before they moved into South Asia. This article caught the attention of French linguist Émile Benveniste. They started a helpful exchange of ideas.

From 1931 to 1933, Dumézil taught French at Uppsala University in Sweden. There, he met important professors and students. These included Stig Wikander and Otto Höfler. These scholars became his lifelong friends and research partners. Their work on ancient Germanic and Indo-Iranian warriors greatly influenced Dumézil.

Return to France and New Ideas

Dumézil came back to France in 1933. He got a job at the École pratique des hautes études (EPHE). From 1935 to 1968, he was the Director of Studies for Comparative Religion at EPHE. He taught and researched Indo-European religions. One of his students was Roger Caillois.

At EPHE, Dumézil also attended lectures by Marcel Granet, who studied Chinese culture. Granet's way of studying religions influenced Dumézil. To learn about non-Indo-European cultures, Dumézil learned Chinese. He also gained a deep understanding of Chinese mythology.

In his research on ancient Indo-Iranians, Dumézil got help from Benveniste. Benveniste had been critical of his ideas before. Dumézil changed many of his theories during his early years at EPHE. He started to focus more on ancient social structures than just language. Scholars who influenced him in this were Arthur Christensen and Hermann Güntert. Important books from this time include Ouranos-Varuna (1934) and Flamen-Brahman (1935). Ouranos-Varuna looked at similarities in Greek and Vedic mythology. Flamen-Brahman studied the idea of a special priestly group among the Proto-Indo-Europeans.

In the early 1930s, Dumézil wrote articles for right-wing newspapers. He used the name "Georges Marcenay." He supported an alliance between France and Italy against Nazi Germany. Dumézil strongly opposed Nazism. He also joined a pro-Jewish group called the Grande Loge de France. Because of this, he was later targeted by the Nazis.

The Trifunctional Hypothesis

In the late 1930s, Dumézil started studying Germanic religion. He was influenced by Jan de Vries and Höfler. In 1938, while teaching at Uppsala University, he made a big discovery. He found that early Germanic society had the same social divisions as the early Indo-Iranians.

Based on this, Dumézil created his trifunctional hypothesis. This idea says that ancient Indo-European societies had three main groups:

- Priests: They were in charge of religious and legal matters.

- Warriors: They were responsible for fighting and protection.

- Commoners: They handled farming, wealth, and general well-being.

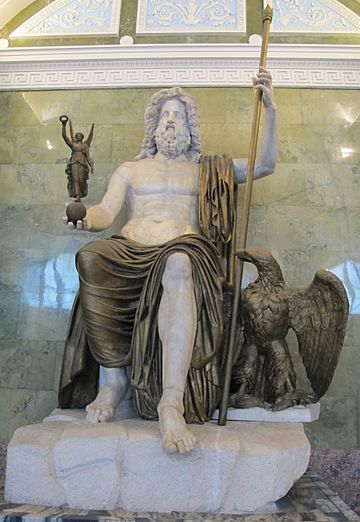

In Norse mythology, Dumézil believed these functions were shown by gods like Týr and Odin (priests), Thor (warriors), and Njörðr and Freyr (commoners). In Vedic mythology, they were represented by Varuna and Mitra, Indra, and the Aśvins. Dumézil's idea changed how modern scholars studied ancient civilizations.

World War II and Expanding Ideas

Before World War II, Dumézil returned to military service. He was a captain in the French Army. In April 1940, he was sent to Ankara, Turkey. He stayed there during the war. He came back to France in September 1940 and continued teaching.

However, because he had been a Freemason, the pro-Nazi Vichy government fired him in 1941. But with help from his colleagues, he got his job back in 1943.

During the war, Dumézil changed his theories. He applied his trifunctional hypothesis to the study of Indo-Iranians. In his book Mitra-Varuna (1940), he suggested that the Indo-Iranian gods Mitra and Varuna represented different aspects of power. He believed these ideas came from an older Indo-European tradition. He also applied his ideas to ancient Rome in books like Jupiter, Mars, Quirinus (1941).

After the War

After World War II, Dumézil focused on comparing Vedic, Roman, and Norse myths. He brought Claude Lévi-Strauss and Mircea Eliade to EPHE. These three scholars are seen as some of the most important mythologists ever.

Dumézil published many important works in the late 1940s. These included Loki (1948) and L'Héritage Indo-Européen à Rome (1949). He also studied the role of the god Aryaman and his counterparts in other Indo-European myths. Dumézil believed that the trifunctional structure was special to Indo-Europeans. He studied languages and myths of indigenous peoples of the Americas. He found that trifunctionalism was not common among them.

Dumézil was elected to the Collège de France in 1949. He held a special position there until 1968, called Chair of Indo-European Civilization. In the 1950s and 1960s, more scholars started to accept his ideas. His friends like Émile Benveniste and Stig Wikander helped spread his theories.

Some scholars, like Paul Thieme, criticized Dumézil. They disagreed with some of his ideas about Indo-Iranian religion. Dumézil always responded strongly to criticism. He also kept improving his theories. He started to see the trifunctional structure more as an idea or way of thinking, rather than a strict system.

In 1955, Dumézil was a visiting professor at the University of Lima in Peru. He spent time studying the language and myths of the Quechua people. In the 1950s, he also researched the idea of a "war" between the different functions in Indo-European mythology. He thought this war ended with the third function (commoners) being included in the first two (priests and warriors). His book L'Idéologie tripartie des Indo-Européens (1958) is a good introduction to his main ideas.

Later Life and Legacy

Dumézil retired from teaching in 1968. But he kept researching and writing until he died. He eventually became skilled in more than 40 languages. These included all branches of Indo-European languages, most languages of the Caucasus, and some indigenous languages of the Americas. He is even credited with helping save the Ubykh language from disappearing.

His most important work, Mythe et epopee (Myth and Epic), was published in three volumes from 1968 to 1973. It gave a full overview of the trifunctional idea in Indo-European mythology. He won the Prix Paul Valery for this work in 1974.

Dumézil's research is seen as a major reason why Indo-European studies and comparative mythology became popular again in the late 20th century. He was considered the world's top expert on comparing Indo-European myths. Many of his books were translated into English, especially in the United States. Scholars like Jaan Puhvel and C. Scott Littleton were inspired by his theories.

He became an Honorary Professor at the Collège de France in 1969. He also became a member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in 1970. In 1975, he was elected to the very respected Académie française. Claude Lévi-Strauss supported his election. Dumézil received many other honors and awards from around the world.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Dumézil continued his research. He focused on the Indo-European parts of Ossetian and Scythian mythology. His book Mitra-Varuna was re-published in 1977. He received the Prix mondial Cino Del Duca in 1984.

In his later years, Dumézil was a well-known figure in France. He was often interviewed. Some political figures admired his theories. However, Dumézil always kept his work separate from politics. He said his studies were not political.

Discussions about Political Views

After Dumézil's death, some scholars criticized him. They suggested he had secret Fascist sympathies. They pointed out that his friend Pierre Gaxotte was involved with a far-right group. They also noted that his work influenced some right-wing thinkers.

However, Dumézil never joined the Action Française, a far-right group. He said he disagreed with many of their beliefs. He also joined the Free Masons in the 1930s. Because of this, the Vichy State (which worked with the Nazis) fired him from his teaching jobs during World War II. This shows he was not aligned with the Nazis.

Some critics, like Colin Renfrew, argued that the patterns Dumézil found in Indo-European myths were not unique to them. They thought these patterns might be found in all human cultures. The strongest critics were Arnaldo Momigliano and Carlo Ginzburg. They said Dumézil had "sympathy for Nazi culture" because of his writings on Germanic religion. They also claimed his ideas were like Fascism.

Many colleagues defended Dumézil, including C. Scott Littleton and Jaan Puhvel. They saw the criticism as politically motivated. Dumézil himself strongly denied the accusations. He said he was never a Fascist and did not agree with their ideas. He explained that he preferred a system where the leader was protected from sudden changes, like a constitutional monarchy.

Death and Lasting Impact

Georges Dumézil passed away in Paris on October 11, 1986, from a stroke. He chose not to write his life story. He believed his work should speak for itself. However, he gave interviews to his supporter, Didier Eribon, shortly before he died. These interviews were published in a book called Entretiens avec Georges Dumézil (1987).

Even after his death, some accusations of Fascist sympathies continued. But a book by Eribon, Faut-il brûler Dumézil? (1992), helped to disprove these claims.

Throughout his life, Dumézil published over 75 books and hundreds of articles. His research still has a big impact on scholars today. These include experts in Indo-European studies, classical studies, Celtic studies, Germanic studies, and Indology.

Many famous scholars were influenced by Dumézil. His work, along with that of Marija Gimbutas, forms the basis for modern Indo-European studies. His idea of the trifunctional hypothesis is considered one of the most important academic achievements of the 20th century. Since 1995, the Académie Française gives an annual award called the Prix Georges-Dumézil for works in philology.

Honors and Awards

Honors

- Officier of the Legion of Honour

- Croix de Guerre 1914-1918

- Commander of the Ordre des Palmes académiques

Acknowledgement

- Member of the Académie française

- Member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres

- Member of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium

- Member of the Austrian Academy of Sciences

- Member of the Royal Irish Academy

Honorary Degrees

- University of Liège

- University of Bern

- Uppsala University

- Istanbul University

Awards

- Prix mondial Cino Del Duca

Personal Life

Georges Dumézil married Madeleine Legrand in 1925. They had two children, a son and a daughter.

Selected Works

- Le crime des Lemniennes: rites et legendes du monde egeen, Geuthner (Paris), 1924.

- Le festin d'immortalite: Etude de mythologie comparee indo-europenne, Volume 34, Annales du MuseeGuimet, Bibliothèque d'etudes, Geuthner (Paris), 1924.

- Le probleme des Centaures: Etude de mythologie comparee indo-europenne, Volume 41, Annales du MuseeGuimet, Bibliothèque d'etudes, Geuthner (Paris), 1929.

- Legendes sur les Nartes, Champion (Paris), 1930.

- La langue des Oubykhs, Champion (Paris), 1931.

- Etudes comparatives sur les langues caucasiennes du nord-ouest, Adrien-Maisonneuve (Paris), 1932.

- Introduction a la grammaire comparee des langues caucasiennes du nord, Champion (Paris), 1933.

- Recherches comparatives sur le verbe caucasien, 1933.

- Ouranos-Varuna: Etude de mythologie comparee indo-europenne, Adrien-Maisonneuve (Paris), 1934.

- Flamen-Brahman, Volume 51, Annales du Musée Guimet, Bibliothèque de vulgarisation, Geuthner (Paris), 1935.

- Contes lazes, Institut d'ethnologie (Paris), 1937.

- Mythes et dieux des Germains: Esai d'interpretation comparative, Leroux (Paris), 1939.

- Jupiter, Mars, Quirinus: Essai sur la conception indo-europennes de la societe et sur les origines de Rome, Gallimard (Paris), 1941.

- Horace et les Curiaces, Gallimard (Paris), 1942.

- Servius et la fortune, Gallimard (Paris), 1943.

- Naissance de Rome: Jupiter, Mars, Quirinus II, Gallimard (Paris), 1944.

- Naissance d'archanges, Jupiter, Mars, Quirinus III: Essai sur la formation de la theologie zoroastrienne, Gallimard (Paris), 1945.

- Tarpeia, Gallimard (Paris), 1947.

- Loki, G. P. Maisonneuve (Paris), 1948.

- Mitra-Varuna: Essai sur deux representations indo-europennes de la souverainete, Gallimard (Paris), 1948, translation by Derek Coltman published as Mitra-Varuna: An Essay on Two Indo-European Representations of Sovereignty, Zone Books (New York, NY), 1988.

- L'heritage indo-europenne a Rome, Gallimard (Paris), 1949.

- Le troiseme souverain: Essai sur le dieu indo-iranien Aryaman et sur la formation de l'histoire mythique d'Irlande, G. P. Maisonneuve, 1949.

- Les dieux des Indo-Europennes, Presses Universitaires de France (Paris), 1952.

- Rituels indo-europennes a Rome, Klincksieck (Paris), 1954.

- Aspects de la fonction guerriere chez les Indo-Europennes, Presses Universitaires de France (Paris), 1956.

- Deesses latines et mythes vediques, Collection Latomus (Brussels), 1956.

- (Editor and translator) Contes et legendes des Oubykhs, Institut d'ethnologie (Paris), 1957.

- L'ideologie tripartie des Indo-Europennes, Collection Latomus, 1958.

- Etudes oubykhs, A. Maisonneuve, 1959.

- Notes sur le parler d'un Armenien musulman de Hemsin, Palais des Academies (Brussels), 1964.

- (Editor and translator) Le livre des heros, Gallimard (Paris), 1965.

- Les dieux des Germains: Essai sur la formation de la religion scandinave, Presses Universitaires de France (Paris), 1959, translation published in Mythe et epopee, three volumes, Gallimard (Paris), 1968–73.

- Documents anatoliens sur les langues et les traditions du Caucase, A. Maisonneuve, 1960.

- La religion romaine archaique, Payot (Paris), 1966, translation by Philip Krapp published as Archaic Roman Religion, University of Chicago Press (Chicago, IL), 1970.

- The Destiny of the Warrior, translation by Alf Hiltebeitel, University of Chicago Press (Chicago, IL), 1970.

- Du myth au roman: La saga de Hadingus, Press universitaires de France (Paris), 1970, translation by Derek Coltman published as From Myth to Fiction: The Saga of Hadingus, University of Chicago Press (Chicago, IL), 1973.

- Heur et malheur de guerrier, second edition, Presses Universitaires de France (Paris), 1970.

- Gods of the Ancient Northmen, University of California Press (Berkeley), 1973.

- The Destiny of a King, translation by Alf Hiltebeitel, University of Chicago Press (Chicago, IL), 1974.

- Fetes romaines d'ete et d'automne suivi de Dix questions romaines, Gallimard (Paris), 1975.

- Les dieux souverains des indo-europennes, Gallimard (Paris), 1977.

- Romans de Scythie et d'alentour, Payot (Paris), 1978.

- Discours, Institut de France (Paris), 1979.

- Mariages indo-europennes, suivi de Quinze questions romaines, Payot (Paris), 1979.

- Camillus: A Study of Indo-European Religion as Roman History, translation by Annette Aronowicz and Josette Bryson, University of California Press (Berkeley), 1980.

- Pour un Temps, Pandora Editions (Paris), 1981.

- La courtisane et les seigneurs colores, et autres essais, Gallimard (Paris), 1983.

- The Stakes of the Warrior, University of California Press (Berkeley), 1983.

- L'Oubli de l'homme et l'honneur des dieux, Gallimard (Paris), 1986.

- The Plight of a Sorceror, University of California Press (Berkeley, CA), 1986.

- Apollon sonore et autres essais: vingt-cinq esquisses de mythologie, Gallimard (Paris), 1987.

- Entretiens avec Didier Eribon, Gallimard (Paris), 1987.

- Le Roman des jumeaux et autres essais: vingt-cinq esquisses de mythologie, Gallimard (Paris), 1994.

- Archaic Roman Religion: With an Appendix on the Religion of the Etruscans, Johns Hopkins University Press (Baltimore, MD), 1996.

- The Riddle of Nostradamus: A Critical Dialogue, translated by Betsy Wing, Johns Hopkins University Press (Baltimore, MD), 1999.

See also

In Spanish: Georges Dumézil para niños

In Spanish: Georges Dumézil para niños

- Hector Munro Chadwick

- John Colarusso

- Dennis Howard Green

- Winfred P. Lehmann

- J. P. Mallory

- Franz Rolf Schröder

- Calvert Watkins

- Martin Litchfield West

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |