History of African Americans in Chicago facts for kids

The history of African Americans in Chicago began in the 1780s with Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, the city's founder, who was of African and French descent from Haiti. The first Black community in Chicago was formed in the 1840s by people who had escaped slavery and those who were already free. By the late 1800s, the first Black person was elected to public office in the city.

Between 1910 and 1960, a huge movement called the Great Migration brought hundreds of thousands of African Americans from the Southern states to Chicago. They moved from living mostly in rural areas to becoming a large part of the city's population. In Chicago, they built churches, community groups, businesses, and created new music and literature. African Americans from all walks of life built strong communities on the South Side and West Side of Chicago for many years, even before the Civil Rights Movement. Even though they often lived in separate neighborhoods, they worked to create places where they could thrive and shape their own future in the History of Chicago.

Contents

Early History of Black Chicago

First Settlers and Growth

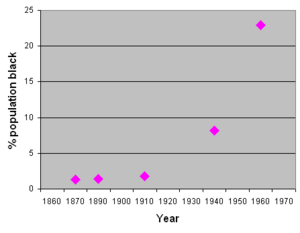

Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, who founded Chicago in the 1780s, was a Black man from Haiti. Even though his settlement started early, African Americans truly became a community in Chicago around the 1840s. By 1860, about 1,000 Black people lived in the city. Many of these were people who had escaped slavery from the Upper South. After 1877, more African Americans moved from the Deep South to Chicago. This caused the Black population to grow from about 4,000 in 1870 to 15,000 by 1890.

In 1853, a law was passed in Illinois that tried to stop all African Americans, including free people, from settling in the state. However, in 1865, Illinois removed these "Black Laws." It was the first state to approve the 13th Amendment, which ended slavery. This was partly thanks to the hard work of John and Mary Jones, a wealthy and active couple who fought for Black rights.

After the Civil War, Illinois had some of the most advanced laws against discrimination in the country. School segregation was made illegal in 1874, and segregation in public places was outlawed in 1885. In 1870, African-American men in Illinois were given the right to vote for the first time. In 1871, John Jones, a tailor and manager of an Underground Railroad station, became the first African-American elected official in the state. He served on the Cook County Commission. By 1879, John W. E. Thomas from Chicago became the first African American elected to the Illinois General Assembly. This started the longest continuous period of African-American representation in any state legislature in U.S. history. After the Great Chicago Fire, Chicago's mayor, Joseph Medill, appointed the city's first Black fire company and the first Black police officer.

The Great Migration to Chicago

As the 1900s began, Southern states passed new laws that took away voting rights from most Black people and many poor white people. Without the right to vote, they could not serve on juries or run for office. They had to follow unfair laws made by white lawmakers, including laws that separated people by race in public places. Schools and other services for Black children often received very little money in the poor, farming economy of the South. As white-led governments passed "Jim Crow" laws to keep white people in charge and create more rules for public life, violence against Black people increased. This included terrible acts of violence used to control Black communities. Also, problems with crops ruined much of the cotton industry. Because of these issues, Black people started moving from the South to the North. They hoped to live more freely, get their children educated, and find new jobs.

The growth of industries for World War I brought thousands of workers to the North. Industries like railroads, meatpacking, and steel also grew quickly. Between 1915 and 1960, hundreds of thousands of Black Southerners moved to Chicago. They wanted to escape violence and segregation and find better economic opportunities. They changed from being mostly farmers to living mostly in cities. This "Great Migration" completely changed Chicago, both in its politics and its culture.

From 1910 to 1940, most African Americans who moved North came from rural areas. They had mostly been farm workers, though some owned land but lost it due to crop problems. Because Black schools in the South had been underfunded for years, many were not highly educated and had few skills for city jobs. Like European immigrants from rural areas, they had to quickly learn how to live in a different city culture. Many took advantage of better schools in Chicago, and their children learned quickly. After 1940, when a second, larger wave of migration began, Black migrants often came from Southern cities and towns. These migrants were usually more ambitious, better educated, and had more city skills for their new homes.

The large number of new people arriving in cities caught everyone's attention. At one point in the 1940s, 3,000 African Americans were arriving in Chicago every week. They stepped off trains from the South and found their way to neighborhoods they had heard about from friends and The Chicago Defender newspaper. The Great Migration was closely watched and studied. White people in Northern cities started to worry as their neighborhoods changed quickly. At the same time, new and older immigrant groups competed for jobs and housing with the new arrivals, especially on the South Side, where the steel and meatpacking industries had many working-class jobs.

As Chicago's industries kept growing, new opportunities opened up for migrants, including Southerners, to find work. The railroad and meatpacking industries hired Black workers. Chicago's African-American newspaper, the Chicago Defender, made the city well known in the South. It sent bundles of papers South on the Illinois Central trains, and African-American Pullman Porters would drop them off in Black towns. Chicago was the easiest Northern city for African Americans in Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas to reach by train. Between 1916 and 1919, 50,000 Black people came to live in the growing Black neighborhoods, creating new needs for the services on the South Side.

The 1919 Race Riot

The Chicago race riot of 1919 was a terrible conflict that started on the South Side on July 27 and ended on August 3, 1919. It involved white Americans attacking Black Americans. During the riot, 38 people died (23 Black and 15 white). Over the week, 537 people were injured, with two-thirds of them being Black. About 1,000 to 2,000 people, mostly Black, lost their homes. Because of its lasting violence and wide-reaching economic effects, it is seen as the worst of the many riots and disturbances across the nation during the ""Red Summer" of 1919." This summer was named for the racial and labor violence and deaths that occurred.

Life in Segregated Chicago

Housing Challenges

Between 1900 and 1910, Chicago's African-American population grew very quickly. Unfriendly attitudes from white residents and the growing population led to the creation of a specific Black neighborhood, or ghetto, on the South Side. Nearby areas were often controlled by Irish immigrant groups, who were very protective of their neighborhoods against any other groups moving in. Most of this large Black population were new migrants. In 1910, more than 75 percent of Black people lived in mostly Black parts of the city. The few neighborhoods that had been set aside for Black settlement in 1900 remained the center of Chicago's African-American community. The "Black Belt" slowly grew as African Americans, despite facing violence and unfair housing rules, moved into new neighborhoods. As the population grew, African Americans became more limited to a specific area instead of spreading throughout the city. When Black people moved into mixed neighborhoods, unfriendly feelings from white ethnic groups increased. After conflicts over the area, white residents often left, and the area became mostly Black. This is one reason the Black Belt region formed.

The Black Belt of Chicago was a series of neighborhoods on the South Side where three-quarters of the city's African-American population lived by the mid-1900s. In the early 1940s, white residents in certain blocks created "restrictive covenants." These were legal agreements that stopped individual owners from renting or selling to Black people. These contracts limited the housing available to Black tenants, causing many Black residents to live in the Black Belt, one of the few neighborhoods open to them. The Black Belt stretched 30 blocks along State Street on the South Side and was usually no more than seven blocks wide. With so many people in this small area, overcrowding often meant many families lived in old and run-down buildings. The South Side's "Black Belt" also had areas based on wealth. The poorest residents lived in the oldest, northern part of the Black Belt, while wealthier Black families lived in the southernmost part. In the mid-20th century, as African Americans across the United States fought against economic limits caused by segregation, Black residents in the Black Belt tried to create more economic opportunities in their community by supporting local Black businesses and entrepreneurs. During this time, Chicago was seen as the capital of Black America. Many African Americans who moved to Chicago's Black Belt came from the Southeastern United States.

Overcrowding was also made worse by other immigrants coming to Chicago, especially lower-class newcomers from rural Europe who also needed cheap housing and working-class jobs. More and more people tried to fit into small "kitchenette" apartments and basement units. Living conditions in the Black Belt were similar to those in other poor areas of the city. Although there were some decent homes in Black sections, the main part of the Black Belt was a slum. A 1934 study estimated that Black households had 6.8 people on average, while white households had 4.7. Many Black people lived in apartments without proper plumbing, often with only one bathroom for an entire floor. With buildings so crowded, building checks and garbage collection were not good enough for healthy living. This unhealthy environment increased the risk of disease. From 1940 to 1960, the rate of infant deaths in the Black Belt was 16% higher than in the rest of the city.

In 1946, the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) tried to ease the overcrowding in Black neighborhoods. They suggested building public housing in less crowded areas of the city. However, white residents did not like this idea. So, city politicians made the CHA keep things as they were and build tall housing projects in the Black Belt and on the West Side. Some of these projects later faced many problems. As industries changed in the 1950s, many jobs were lost, and residents changed from working-class families to poor families needing help.

Vibrant Culture and Arts

Between 1916 and 1920, nearly 50,000 Black Southerners moved to Chicago, which greatly shaped the city's growth. This growth increased even faster after 1940. The new residents helped local churches, businesses, and community groups grow. A new music culture emerged, drawing from all the traditions along the Mississippi River. The population continued to grow with new migrants, with most arriving after 1940.

Chicago's Black arts community was especially lively. The 1920s were the peak of the Jazz Age, but music remained central to the community for decades. Famous musicians became well-known in Chicago. Along the "Stroll," a lively entertainment area on State Street, jazz legends like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Bessie Smith, and Ethel Waters performed at clubs like the Deluxe Cafe.

Black writers in Chicago were also very active from 1925 to 1950. The city's Black Renaissance was as important as the Harlem Renaissance. Important writers included Richard Wright, Willard Motley, William Attaway, Frank Marshall Davis, St. Clair Drake, Horace R. Cayton, Jr., and Margaret Walker. Chicago was also home to writer and poet Gwendolyn Brooks, who wrote about the lives of Black working-class people in the crowded apartments of Bronzeville. These writers showed the changes and challenges Black people faced in city life and their efforts to build new worlds. In Chicago, Black writers moved away from the folk traditions popular in the Harlem Renaissance. Instead, they used a more realistic style to show life in the city's Black neighborhoods. The famous book Black Metropolis, written by St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Jr., is a great example of the Chicago writers' style. Today, it is still the most detailed picture of Black Chicago in the 1930s and 1940s.

Since 2008, the West Side Historical Society, led by Rickie P. Brown Sr., has been documenting the rich history of the West Side of Chicago. Their research showed that the Austin community has the largest Black population in Chicago. This means that when you include the Near West Side, North Lawndale, West Humboldt Park, Garfield Park, and Austin communities, the largest number of Black people live on the West Side. Their efforts to build a museum on the West Side and to raise awareness for Juneteenth as a national holiday were recognized with a special announcement in 2011 by Governor Pat Quinn.

Black Businesses and Jobs

Chicago's Black population developed different social classes. There were many domestic workers and other manual laborers, along with a small but growing group of middle- and upper-class business owners and professionals. In 1929, Black Chicagoans gained access to city jobs, which helped their professional class grow. Fighting job discrimination was a constant struggle for African Americans in Chicago. Managers in many companies limited the progress of Black workers, often preventing them from earning higher wages. In the mid-20th century, Black people slowly began to move into better job positions.

The migration of Black people to Chicago created a larger market for African-American businesses. The most important success in Black business was in the insurance field. Four major insurance companies were founded in Chicago. Later, in the early 1900s, service businesses became more common. The African-American market on State Street at this time included barber shops, restaurants, pool rooms, saloons, and beauty salons. African Americans used these businesses to build their own communities. These shops gave Black people a chance to establish their families, earn money, and become an active part of the community.

Black Political Power

With a growing population and strong leaders in city politics, Black people began to win elections for local and state government. The first Black people were elected to office in Chicago in the late 1800s, many years before the Great Migrations. Chicago elected the first African-American member of Congress after the Reconstruction era. This was Republican Oscar Stanton De Priest, who served from 1929 to 1935 for Illinois' 1st congressional district. This district has continuously elected African Americans to Congress ever since. The Chicago area has elected 18 African Americans to the House of Representatives, more than any other state. William L. Dawson represented the Black Belt in Congress from 1943 until his death in 1970. He started as a Republican but switched to the Democratic party, like most of his voters, in the late 1930s. In 1949, he became the first African American to lead a congressional committee.

Chicago is home to three of the eight African-American United States Senators who have served since the Reconstruction period. All three are Democrats: Carol Moseley Braun (1993–1999), Barack Obama (2005–2008), and Roland Burris (2009–2010).

Barack Obama moved from the Senate to the White House in 2008, becoming the first African-American President of the United States.

Electing a Black Mayor in 1983

In the Democratic primary election on February 22, 1983, the votes were split three ways. On the North and Northwest Sides of Chicago, the current mayor Jane Byrne was ahead, and future mayor Richard M. Daley, son of the late Mayor Richard J. Daley, came in a close second. The Black leader Harold Washington won by huge majorities on the South and West Sides. Voters on the Southwest Side strongly supported Daley. Washington won the primary with 37% of the vote, compared to 33% for Byrne and 30% for Daley. Winning the Democratic primary was usually like winning the election itself in Chicago, which was a strong Democratic city. However, after his primary win, Washington found that his Republican opponent, former state legislator Bernard Epton, was supported by many high-ranking Democrats and their local political groups.

Epton's campaign mentioned Washington's past conviction for not filing income tax returns (he had paid the taxes but not filed the paperwork). Washington, on the other hand, focused on changing Chicago's political system and the need for a jobs program during a tough economy. In the general mayoral election on April 12, 1983, Washington defeated Epton by 3.7%, with 51.7% of the vote to Epton's 48.0%. He became the first Black mayor of Chicago. Washington was sworn in as mayor on April 29, 1983, and left his Congressional seat the next day.

Achievements and Progress

In the early 1900s, many important African Americans lived in Chicago. These included Republican and later Democratic congressman William L. Dawson (who was America's most powerful Black politician) and boxing champion Joe Louis. America's most widely read Black newspaper, the Chicago Defender, was published there and also sent to the South.

After much effort, in the late 1930s, workers of all races came together to form the United Meatpacking Workers of America. By then, most workers in Chicago's meatpacking plants were Black, but they successfully created a mixed-race organizing committee. This union managed to organize workers in Chicago and Omaha, Nebraska, which had the second-largest meatpacking industry. This union was part of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which was more progressive than the American Federation of Labor. They succeeded in ending job segregation. For a time, workers earned good wages and other benefits, allowing many to live a middle-class life for decades. Some Black workers were also able to move up to supervisor and management roles. The CIO also successfully organized Chicago's steel industry.

Recent Changes

A recent report from the Chicago Tribune stated that thousands of Black families have left Chicago in the past ten years, causing the Black population to decrease by about 10%. Politico reported that Chicago's once thriving Black business community has significantly shrunk, with many Black-owned companies closing. Many Black people leaving Chicago are now moving to cities in the U.S. South, including Atlanta, Charlotte, Dallas, Houston, Little Rock, New Orleans, and San Antonio.

Notable People from Chicago

- Bernie Mac

- Michelle Obama

- Barack Obama

- Jesse Jackson

- Dick Gregory

- Dwyane Wade

- Derrick Rose

- Kanye West

- Tim Hardaway

- Anthony Davis

- Chance the Rapper

- Rhymefest

- Chief Keef

- Redd Foxx

- Sam Cooke

- Earth, Wind, and Fire

- R. Kelly

- Jennifer Hudson

- Shonda Rhimes

- Muhammad Ali

- Curtis Mayfield

- Minnie Riperton

- Louis Armstrong

- Muddy Waters

- Ida B Wells

- Emmett Till

- Lil Durk

- King Von

- G Herbo

- Lil Bibby

- Juice WRLD

- Polo G

- Dreezy

- Cupcakke

- Buddy Guy

- Nat King Cole

- Harold Washington

- Lupe Fiasco

- Twista

- Common

- Chaka Khan

- Keke Palmer

- Noname

- Dantrell Davis

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |