History of Lebanon facts for kids

The history of Lebanon tells the story of the modern country of Lebanon and how it came to be. It also covers the long history of the wider region where Lebanon is located today.

Modern Lebanon has had its current borders since 1920. This was when Greater Lebanon was created under French and British control after World War I. Before 1920, "Lebanon" usually meant the Mount Lebanon mountains and nearby areas like the coast and the Bekaa plains. The idea of an independent Lebanon grew stronger towards the end of the Mount Lebanon Emirate, especially among Maronite Christian leaders.

Contents

Early History of Lebanon

Ancient Times

Long, long ago, people lived in the area that is now Lebanon. One important ancient site is Ksar Akil, near Beirut. Here, scientists found tools and bones from early humans, showing that people lived there about 45,000 years ago. They even found early forms of jewelry, like shells used as pendants. This suggests these early people had modern human behaviors.

Later, the region became home to the Canaanites. These ancient people farmed the land and lived in advanced societies. The Canaanites created the oldest known 24-letter alphabet, which was a shorter version of earlier alphabets. This Canaanite alphabet later became the Phoenician alphabet, which influenced writing across the Mediterranean, including the Greek alphabet.

The Phoenicians: Sea Traders and Explorers

The coastal area of Lebanon was the home of the Phoenicians. They were famous for their trading cities like Byblos, Beirut, Sidon, and Tyre. The Phoenicians were excellent sailors and traders for over 1,000 years. They traded spices from Arabia like cinnamon and frankincense. Their art and customs were influenced by powerful neighbors like Mesopotamia and Egypt.

The Phoenicians were also amazing explorers. Some stories say they were the first to sail all the way around the continent of Africa! The Greek historian Herodotus wrote about this journey, which took three years. Modern historians believe this story because the Phoenicians mentioned seeing the sun on their right side when sailing south, which would only happen if they crossed the Equator.

The Phoenicians founded many colonies around the Mediterranean Sea, including Carthage (in modern-day Tunisia), Tripoli (in Libya), and Cadiz (in Spain). For a long time, the Phoenicians paid tribute to powerful empires like the Assyrians and Babylonians.

Lebanon Under Great Empires

Persian and Greek Rule

Around 539 BC, the Persian Empire, led by Cyrus the Great, conquered the Phoenician cities. The Phoenicians became an important part of the Persian fleet during wars. However, they were punished after a big defeat in the Battle of Salamis.

Later, in 332 BC, Alexander the Great conquered the region during his war against Persia. He famously attacked and burned Tyre. After Alexander's death, the region became part of the Seleucid Empire.

Roman Rule and the Rise of Christianity

In 64 BC, the Romans took control. Christianity arrived in Lebanon from nearby Galilee in the 1st century. The region became an important Christian center.

In the late 4th and early 5th centuries, a hermit named Maron started a new Christian tradition in the Mount Lebanon mountains. His followers, known as Maronites, moved into the mountains to avoid persecution. From 619 to 629, the Persians briefly occupied Lebanon again.

Middle Ages in Lebanon

Islamic Rule

In the 7th century AD, Muslim Arabs conquered Syria, including Lebanon. While Islam and Arabic became dominant, many people, especially the Maronites, kept their Christian faith and a lot of their independence. The nearby city of Damascus became the capital of the Umayyad Caliphate, increasing Muslim influence.

During this time, coastal areas saw more conversions to Islam, but mountain communities largely kept their traditions. Christians and Jews had to pay a special tax called jizya. Trade in the Mediterranean declined for a few centuries due to conflicts.

In the 980s, the Fatimid Caliphate took control of Mount Lebanon. Under their rule, trade improved again, and cities like Tripoli and Tyre became important for exporting goods like cotton, silk, and glass. In the 1020s, the Druze religion began to form in Mount Lebanon, gaining followers in the southern parts.

Crusader Kingdoms

In the 11th century, Christian armies from Western Europe, called Crusaders, came to the Eastern Mediterranean. Lebanon was right in their path to Jerusalem. The southern part of Lebanon became part of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the northern part became the County of Tripoli.

A very important result of the Crusades was the connection between the Crusaders (mostly French) and the Maronites. Unlike other Christians in the region, the Maronites were loyal to the Pope in Rome, so the Franks saw them as fellow Catholics. This led to centuries of support for the Maronites from France and Italy.

Mamluk Rule

By the late 13th century, the Mamluk sultans of Egypt took back control of Lebanon. They rebuilt important ports like Sidon, Beirut, and Tripoli, making Tripoli the main port and a center for Sunni religious education and trade. The Black Death in the 1300s greatly reduced the population and slowed the economy.

Ottoman Rule in Lebanon

From the 16th century, the Ottoman Turks formed a large empire that included Lebanon. The Ottoman sultan Selim I conquered the Mamluks in 1516. The Ottomans gave Lebanese leaders a special semi-independent status. Two main families, the Maans (Druze) and the Chehabs (Sunni Muslims who later became Maronite Christians), ruled Lebanon for the Ottomans until the mid-1800s.

The Maan Dynasty (1517–1697)

The Maans were a powerful family whose influence grew with Fakhr ad-Din I. Their power reached its peak with Fakhr al-Din II (1570–1635).

Fakhr al-Din II: A Visionary Leader

Fakhr al-Din II was born into a Druze family. In 1608, he made an alliance with the Italian Grand Duchy of Tuscany. This alliance included economic and secret military agreements. The Ottomans became worried about his growing power and foreign connections. In 1613, they attacked Lebanon, forcing Fakhr al-Din to go into exile in Tuscany.

While in Europe, he saw the cultural changes of the 17th century. He hoped to get European help to free Lebanon from Ottoman rule, but Europe was more interested in trade. By 1618, he returned to Lebanon and quickly reunited the lands. He brought in printing presses and encouraged Jesuit priests and Catholic nuns to open schools.

In 1623, Fakhr al-Din angered the Ottomans again. This led to a battle where his forces, though outnumbered, won a big victory. However, the Ottomans grew more concerned about his power. In 1632, Sultan Murad IV ordered an attack on Lebanon. Fakhr al-Din was defeated and later executed in Istanbul in 1635.

Fakhr al-Din II is remembered as a great leader who improved Lebanon's military and economy. He was known for religious tolerance and tried to unite the different religious groups. He is seen by many Lebanese as the best leader the country has ever had.

The Shihab Dynasty (1697–1842)

The Shihabs took over from the Maans in 1697. They were originally Sunni Muslims but converted to Christianity in the late 1700s.

Emir Bashir II: A Time of Change

The most famous Shihab ruler was Bashir Shihab II, who ruled from 1789 to 1840. He was a skilled leader who managed to stay neutral when Napoleon attacked nearby Acre in 1799.

Bashir II tried to reform taxes and change the old feudal system. He faced a strong rival, also named Bashir, from the Druze community. Conflicts between Maronites and Druze grew, especially when Bashir II, a Maronite, seemed to favor Christians. In 1825, Bashir II defeated his rival. He then worked with France and the Egyptian Pasha Muhammad Ali, who took control of Lebanon in 1832.

During the 19th century, Beirut became a very important port. This was because Mount Lebanon became a major center for producing silk for export to Europe, especially France. This made the region wealthy but also dependent on Europe.

Growing Tensions and European Involvement

Discontent grew into open rebellion. In 1841, conflicts between the Druze and Maronite Christians exploded. There were massacres, and the Ottomans tried to create peace by dividing Mount Lebanon into Christian and Druze districts. This only made things worse, leading to more civil conflict.

In 1860, a full-scale sectarian war broke out. France supported the Maronite Christians, while Britain backed the Druze. The Druze began burning Maronite villages and committing massacres. European powers intervened, and French troops were sent to Beirut. The outcome was that the Maronites were confined to a mountainous area, cut off from Beirut and the fertile Bekaa Valley.

Despite these conflicts, the late 19th century saw some stability. Muslim, Druze, and Maronite groups focused on economic and cultural development. This period saw the founding of the American University of Beirut and a flourishing of literature.

The Great Famine (1915–1918)

During World War I, Lebanon suffered a terrible famine. About half the population of Mount Lebanon, mostly Maronites, died from starvation. This was caused by crop failures, harsh Ottoman rule, a naval blockade by the Allies, and an Ottoman ban on exports to Lebanon. People were so desperate that some resorted to eating street animals.

French Mandate and Independence

French Control (1920–1939)

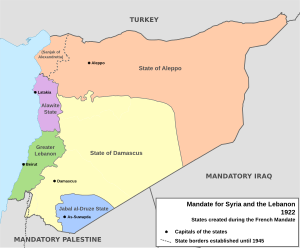

After the Ottoman Empire collapsed following World War I, the League of Nations gave France control over the five provinces that make up modern Lebanon. France wanted to expand its control and ensure a strong border. They added the Beqaa Valley and coastal cities like Beirut, Tripoli, and Sidon to Lebanon.

This greatly changed Lebanon's population. The added territories had many Muslims, so Christians, especially Maronites, were no longer a clear majority. Lebanon's 1926 constitution tried to balance power among religious groups. The president had to be a Christian (usually Maronite), and the prime minister a Sunni Muslim. Parliament seats were divided based on a six-to-five Christian/Muslim ratio.

World War II and Independence (1940–1943)

During World War II, the French government in Lebanon was controlled by Vichy France. Britain, fearing Nazi Germany's influence, sent its army into Lebanon and Syria. After the fighting, General Charles de Gaulle recognized Lebanon's independence.

On November 26, 1941, Lebanon was declared independent under the Free French government. Elections were held in 1943, and the new Lebanese government declared an end to the French mandate. The French briefly imprisoned the new government, but due to international pressure, they were released on November 22, 1943. This date is celebrated as Lebanese Independence Day.

The Republic of Lebanon

Early Years and Prosperity

The last French troops left Lebanon in 1946. After independence, Lebanon experienced periods of stability and growth. Beirut became a major center for finance, trade, and tourism, earning the nickname "Paris of the Middle East."

After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Lebanon became home to over 110,000 Palestinian refugees. In 1958, there was a brief uprising, and United States Marines were sent to Beirut to help.

During the 1960s, Lebanon enjoyed economic success, becoming one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. However, this prosperity was shaken by the collapse of the country's largest bank, Intra Bank, in 1966.

Growing Tensions and the PLO

More Palestinian refugees arrived after the 1967 Arab–Israeli War. Thousands of Palestinian fighters, led by Yasser Arafat's Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), moved to Lebanon after being defeated in Jordan. They began using southern Lebanon to launch attacks on Israel.

These attacks led to Israeli retaliation. In 1968, an Israeli commando raid destroyed civilian planes at Beirut's airport. This event divided Lebanese society, with Muslims generally supporting the Palestinians and Maronites opposing them. This disagreement deepened the tensions between Christian and Muslim communities over political power.

In 1969, the "Cairo Agreement" gave the PLO control over Palestinian refugee camps and access to northern Israel, in exchange for respecting Lebanese sovereignty. This angered Maronites, who felt too many concessions were made. Pro-Maronite groups like the Phalange militia grew stronger.

The PLO used its new freedom to create a "mini-state" in southern Lebanon and increase attacks on Israel. This led to more Israeli bombing raids in southern Lebanon. The cycle of attacks and retaliation escalated, eventually leading to the civil war.

The Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990)

Dark Green – controlled by Syria;

Purple – controlled by Maronite groups;

Light Green – controlled by Palestinian militias

The Lebanese Civil War began in 1975. It was caused by many factors, including Lebanon's diverse religious groups, changing population numbers, conflicts between religions, and the influence of Syria, the PLO, and Israel. Lebanon had Maronite Christians, Eastern Orthodox Christians, Sunni Muslims, and Shia Muslims, along with Druze, Kurds, Armenians, and Palestinian refugees.

The war was very destructive, killing over 100,000 people and displacing about 900,000. It can be divided into several periods: the initial outbreak, Syrian and Israeli interventions, and the final resolution.

Christian control of the government, guaranteed by the constitution, was increasingly challenged by Muslims and leftists. This led to full-scale civil war in April 1975. Syria intervened in 1976, sending troops into Lebanon.

In the south, fighting between Israel and the PLO led Israel to support the South Lebanon Army (SLA) to create a security zone. In March 1978, Israel invaded Lebanon in response to PLO attacks. The UN Security Council called for an Israeli withdrawal and created the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) to keep peace.

In June 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon again in "Operation Peace for Galilee." Israeli forces reached Beirut, and Yassir Arafat and the PLO were evacuated. A multinational force (including U.S. Marines, French, and Italian units) arrived to help.

On September 14, 1982, Bashir Gemayel, a Maronite leader who had been elected president, was assassinated. This led to the Sabra and Shatila massacre, where between 700 and 3,500 Palestinians were killed in refugee camps by Phalangist militias.

Bashir Gemayel's brother, Amine Gemayel, became president. He tried to get Israeli and Syrian forces to leave. In 1983, the Israeli army withdrew south, leading to the Mountain War between Druze and Maronite forces. The Druze won, and many Christians were forced to leave Southern Mount Lebanon.

Attacks on U.S. and Western interests, like the bombings of the US Embassy and Marine barracks in 1983, led to an American withdrawal. From 1985 to 1989, heavy fighting, known as the "War of the Camps," took place between the Shi'a Muslim Amal militia and Palestinians.

By 1988, Lebanon was divided, with a Christian government in East Beirut and a Muslim government in West Beirut, and no president. In 1989, the Taif Agreement was signed, marking the beginning of the end of the war. It led to political reforms, including expanding the National Assembly and dividing seats equally between Christians and Muslims.

In May 1991, most militias were disbanded, and the Lebanese Armed Forces began to rebuild. The civil war officially ended on October 13, 1990, with Syria playing a key role in its conclusion.

Modern Lebanon

Post-War Recovery and Challenges

After the war, Lebanon held elections, and many militias were weakened. The Lebanese army began to control most of the country. Only Hezbollah kept its weapons, supported by the Lebanese parliament for defending against Israeli occupation. Syrian troops remained in Lebanon, influencing government institutions. Israeli forces left southern Lebanon in May 2000, but the Syrian presence continued.

In 1992, Rafiq Hariri, a successful businessman, became prime minister. He focused on rebuilding the country and economy. Much of the civil war damage was repaired, and foreign investors and tourists returned. However, Lebanon became heavily indebted.

Syria's continued military presence was criticized by some Lebanese, especially Maronite Christians and Druze, and later by Sunni Muslims. Shia Muslims and Hezbollah supported the Syrian presence. The United States and France pushed Syria to withdraw. In 2004, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1559, calling for all foreign forces to leave Lebanon and for militias to disarm.

On February 14, 2005, former Prime Minister Hariri was assassinated in a car bomb attack. This sparked huge protests, known as the Cedar Revolution, demanding Syria's withdrawal.

Cedar Revolution and 2006 War (2005–2006)

On April 26, 2005, the last Syrian troops left Lebanon. After their withdrawal, a series of assassinations of anti-Syrian politicians and journalists began.

Hezbollah became part of the Lebanese government after the 2005 elections. However, its armed militia remained a point of tension, especially with UN calls for its disarmament.

The 2006 Lebanon War was a 34-day conflict between Hezbollah and the Israeli military. It started on July 12, 2006, and ended with a UN-brokered ceasefire on August 14, 2006.

Recent Instability and Syrian War Spillover

In 2007, the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp was the site of a conflict between the Lebanese Army and Fatah al-Islam. From 2006 to 2008, political protests led to a power-sharing agreement in 2008, which ended 18 months of political deadlock.

In 2011, the national unity government collapsed due to tensions over the investigation into Hariri's assassination. The Syrian Civil War (starting in 2011) also caused problems in Lebanon, leading to sectarian violence and a large influx of Syrian refugees.

In October 2019, widespread protests began across Lebanon due to government failures and a severe financial crisis. The government had failed to address issues like wildfires and a lack of basic services. Commercial banks imposed limits on dollar withdrawals, causing further economic hardship. The protests led to the resignation of Prime Minister Saad Hariri.

Economic Crisis and Beirut Explosion

In March 2020, the Banque du Liban (BdL), Lebanon's central bank, defaulted on its debt, causing the value of the Lebanese pound to collapse. This led to a deep economic crisis.

On August 4, 2020, a massive explosion occurred at the port of Beirut, destroying many buildings and killing over 200 people. This led to more protests and the resignation of the government. A state of emergency was declared.

In October 2021, clashes erupted in Beirut between the Christian militia Lebanese Forces and Hezbollah fighters.

In May 2022, Lebanon held elections. The Iran-backed Shia Muslim Hezbollah movement and its allies lost their parliamentary majority, though Hezbollah itself kept its seats. A rival Christian party, the Lebanese Forces, gained seats. As of 2023, Lebanon continues to face severe poverty, economic problems, and a banking collapse.

Recent Events (2023-2025)

The Gaza war that began in October 2023 led to a new conflict between Israel and Hezbollah. Hezbollah launched rockets at northern Israel, causing many Israelis to be displaced. Hezbollah stated it would continue attacks until Israel stopped its military operations in Gaza.

In September 2024, the conflict escalated significantly. After the explosion of Hezbollah pagers and walkie-talkies, Israel launched airstrikes on Lebanon, killing hundreds and causing a mass evacuation of Southern Lebanon. On September 27, 2024, Hassan Nasrallah, the long-time leader of Hezbollah, was killed in a large Israeli air attack on Beirut.

In November 2024, a ceasefire deal was signed between Israel and Hezbollah. Hezbollah was given 60 days to end its armed presence in southern Lebanon, and Israeli forces were to withdraw from the area in the same period. The fall of Assad’s government in Syria in December 2024 was another blow to Hezbollah, as Syria had been a key ally. This event was seen as starting a new chapter in Lebanese politics.

In January 2025, Joseph Aoun, the Lebanese army commander, was elected as Lebanon's 14th president after the position had been empty for two years. In February 2025, Nawaf Salam, a former president of the International Court of Justice, formed a new government, which won a vote of confidence in parliament.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del Líbano para niños

In Spanish: Historia del Líbano para niños

- Archaeology of Lebanon

- Constitution of Lebanon

- Foreign relations of Lebanon

- History of the Middle East

- Lebanese Civil War

- Lebanese diaspora

- Politics of Lebanon

- Timeline of Lebanese history

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |