History of Western Sahara facts for kids

The history of Western Sahara goes back a very long time, even to the time of the Carthaginians around 500 BC. Not many records from that time are left. The more recent history of Western Sahara is linked to nomadic groups, like the Sanhaja tribe. These groups lived under Berber tribal rule and had some contact with the Roman Empire. Later, Islam and the Arabic language arrived in the area around 700 AD.

Western Sahara has never been a country in the way we think of countries today. It had some Phoenician settlements, but they disappeared. Islam came in the 700s, but the region was very dry and didn't develop much. From the 1000s to the 1800s, Western Sahara was an important link between southern Africa and North Africa. In the 1000s, the Sanhaja and Lamtuna tribes joined together to create the Almoravid dynasty. This powerful group conquered lands that are now Morocco, western Algeria, and even parts of Spain to the north. To the south, they reached Mauritania and Mali. Later, in the 1500s, the Arab Saadi dynasty conquered the Songhai Empire. Important Trans-Saharan trade routes also crossed Western Sahara.

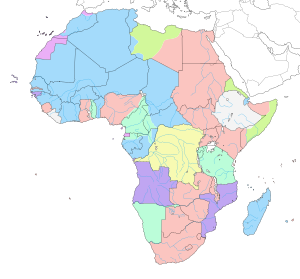

In 1884, Spain claimed control over the coast from Cape Bojador to Cape Blanc. This area later grew bigger. In 1958, Spain combined different areas to form the province of Spanish Sahara.

In 1975, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) looked at Western Sahara's status. They said that even though some tribes had historical ties to Morocco, these ties were not strong enough to give Morocco full ownership of the land. In November 1975, the Green March began. About 300,000 unarmed Moroccans, along with the Moroccan Army, moved towards Western Sahara. Because of pressure from France, the US, and the UK, Spain left Western Sahara on November 14, 1975. Morocco then took control of the northern two-thirds of Western Sahara in 1976. They took the rest of the land in 1979 after Mauritania left.

On February 27, 1976, the Polisario Front officially announced the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). They set up a government that was not in the country itself. This started a guerrilla war between the Polisario and Morocco. The fighting continued until a cease-fire in 1991. As part of the 1991 peace agreement, a vote was supposed to happen among the local people. They would choose between becoming independent or joining Morocco. This vote has not happened yet because there are disagreements about who can vote.

Contents

Ancient Times and Early History

Phoenician and Carthaginian settlements, possibly started by Hanno the Navigator around 500 BC, have almost completely disappeared. The Sahara desert became much drier between 300 BC and 300 AD. This made it very hard to connect with the outside world. Things changed when camels were brought to the area around 300 AD.

Contact with the Roman Empire

Pliny wrote that the coastal area north of the Senegal River and south of the Atlas Mountains had people living there during the time of Emperor Augustus. These people were called the Pharusii and Perorsi.

In the year 41 AD Suetonius Paullinus, who later became a Consul, was the first Roman to lead an army across Mount Atlas. After a ten-day march, he reached the top, which was covered in snow even in summer. From there, after crossing a desert of black sand and burnt rocks, he arrived at a river called Gerj...he then went into the land of the Canarii and Perorsi. The Canarii lived in a forest area with many elephants and snakes, and the Perorsi were Ethiopians, not far from the Pharusii and the river Daras (which is now the Senegal river).

What is now Western Sahara was a dry grassland during ancient times. Independent tribes like the Pharusii and Perorsi lived a semi-nomadic life. They faced increasing desertification, meaning the land was becoming more like a desert.

Romans explored this area. Suetonius Paulinus likely reached the Adrar plateau. We know that Romans traded here because coins and pins (called fibulas) have been found in places like Akjoujt and Tamkartkart.

The people of Western Sahara in the early Roman Empire were mostly nomads. These were mainly from the Sanhaja tribal group. There were also people who lived in one place, in river valleys, oases, and towns. Some of these towns were Awdaghust, Tichitt, Oualata, and Timbuktu.

Some Berber tribes moved to Mauritania in the 200s and 300s. After the 1200s, some Arabs came to the region as conquerors.

Islamic Era

Islam arrived in the 700s AD among the Berber people living in the western Sahara. The Islamic faith spread quickly, brought by Arab immigrants. At first, these Arabs mostly stayed in the cities of what is now Morocco and Spain.

The Berbers used the old trade routes across the Sahara more and more. Caravans carried salt, gold, and slaves between North Africa and West Africa. Controlling these trade routes became very important in the constant power struggles between different tribes. Sometimes, Berber tribes in Western Sahara would unite behind religious leaders. They would overthrow the current rulers and sometimes even start their own ruling families. This happened with the Almoravids, who ruled parts of Morocco and Al-Andalus (Spain). It also happened with the jihad of Nasir al-Din in the 1600s and the Qadiriyyah movement in the 1700s.

Zawiyas

Zawiyas played an important role. These were places where religious teachers, legal experts, and educators lived. The tribes linked to these zawiyas became known as tribes of teachers and specialists.

Arab Influence (1200s and 1300s)

In the 1200s and 1300s, some tribes moved west along the northern edge of the Sahara. They settled in places like Fezzan (Libya), Ifriqiya (Tunisia), and Saguia el-Hamra (Western Sahara).

Important stopping places for trade included Ouadane, Idjil, Azougui, Araouane, and later Tindouf. At the same time, the number of slaves in Western Sahara itself grew a lot.

The Maqil tribes, who entered the lands of the Sanhaja Berber tribe, sometimes married into the Berber population. The people of the region today, who have both Arab and Berber roots, are called Saharawi. The Arabic dialect called Hassaniya became the main language of Western Sahara and Mauritania. Berber words and cultural traditions are still common, even though many Saharawi people today say they have Arab ancestors.

Colonial Era (1884–1975)

Western Sahara came under Spanish rule. This happened even though the Moroccan sultan Hassan I tried to stop European countries from taking over the land in 1886. The oases of Tuat in the southeast became part of the huge French Sahara territory.

In 1912, Morocco itself became a protectorate, meaning it was controlled by Spain and France.

Sahrawi Tribes and Spanish Rule

The modern ethnic group known as Sahrawi are an Arabized Berber people. They live in the western part of the Sahara desert, in areas that are now Mauritania, Morocco, Algeria, and especially Western Sahara. Some tribes traditionally moved into northern Mali and Niger. Like most Saharan peoples, these tribes have a very mixed background. They combine Arab, Berber, and other influences, including characteristics from black African groups.

Before colonial times, the tribal areas of the Sahara desert were generally seen as bled es-Siba, or "the land of dissidence." This meant that the rulers of Islamic states in North Africa, like the Sultan of Morocco, had little control over them. The Islamic governments of empires like Mali and Songhai also had a similar relationship with these lands. These areas were home to independent tribes and were also the main routes for the Saharan caravan trade. Central governments had little power in the region. However, some Hassaniya tribes would sometimes show loyalty to powerful neighboring rulers to get their political support.

A good source of information on the Sahrawi people during Spanish colonial times is the work of Spanish anthropologist Julio Caro Baroja. He spent several months among the native tribes of the then Spanish Sahara in 1952–53.

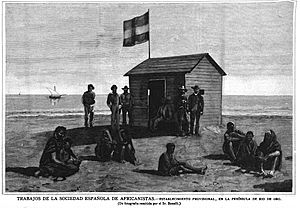

Spanish Sahara

In 1884, Spain claimed a protectorate over the coast from Cape Bojador to Cap Blanc. Later, Spain expanded its control. In 1958, Spain combined the northern area of Saguia el-Hamra and the southern area of Río de Oro to form the province of Spanish Sahara.

The Sahrawi population often fought against Spanish forces, keeping them out of much of the territory for a long time. Ma al-Aynayn led an uprising against the French in the 1910s. French forces finally defeated him. His sons and followers were involved in several rebellions that followed. The territory was not fully controlled until 1934, when Spanish and French forces together destroyed Smara for the second time. Another uprising happened in 1956–1958, started by the Moroccan Army of Liberation. This led to heavy fighting, but Spanish forces, again with French help, regained control. However, unrest continued. In 1967, the Harakat Tahrir group started to peacefully challenge Spanish rule. After the events of the Zemla Intifada in 1970, when Spanish police stopped the organization and its founder, Muhammad Bassiri, disappeared, Sahrawi nationalism became more militant.

Western Sahara Conflict

From 1973, the Spanish rulers slowly lost control of the countryside to the armed guerrillas of the Polisario Front. This was a nationalist organization. Spain tried to create local Sahrawi political groups to support its rule and draw activists away from the nationalists, but these attempts failed. As the health of the Spanish leader Francisco Franco got worse, the government in Madrid became disorganized. They looked for a way to end the conflict in the Sahara. The fall of the Portuguese government in 1974, after unpopular wars in its own African colonies, seemed to speed up Spain's decision to leave.

Armed Conflict (1975–1991)

In late 1975, Spain met with Polisario leader El-Ouali to discuss handing over power. But at the same time, Morocco and Mauritania started putting pressure on the Spanish government. Both countries claimed that Spanish Sahara was historically part of their own lands. The United Nations got involved after Morocco asked the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for an opinion on its claims. The UN also sent a team to Western Sahara to find out what the people wanted. This team reported on October 15, saying there was "an overwhelming consensus" for independence. They also said the Polisario Front seemed to be the main Sahrawi organization.

On October 16, the ICJ gave its decision. The court found that the historical ties of Morocco and Mauritania to Spanish Sahara did not give them the right to the territory. The court also said that the idea of terra nullius (un-owned land) did not apply to the territory. The court declared that the Sahrawi people, as the true owners of the land, had a right to self-determination. This meant any solution (like independence or joining another country) had to be accepted by the people living there. Neither Morocco nor Mauritania accepted this. On October 31, 1975, Morocco sent its army into Western Sahara to attack Polisario positions.

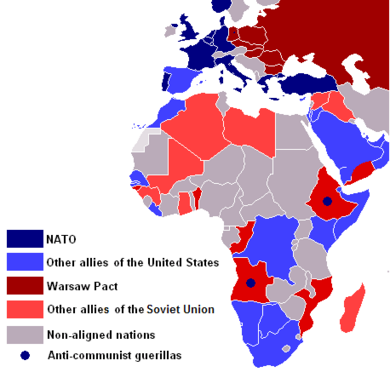

On November 6, 1975, Morocco launched the Green March into Western Sahara. About 350,000 unarmed Moroccans, along with the Moroccan Army, gathered near the city of Tarfaya. They waited for a signal from King Hassan II of Morocco to cross into Western Sahara. Because of international pressure, Spain agreed to Morocco's demands and started talks. This led to the Madrid Agreement and the Western Sahara partition agreement. These treaties divided the control of the territory between Morocco and Mauritania. However, they did not decide who truly owned the land. Spain, Morocco, and Mauritania did not ask the Sahrawi people what they wanted. The Polisario strongly opposed these treaties. The events in the region until the 1990s were greatly influenced by the power struggles of the Cold war. Algeria, Libya, and Mali were allied with the Eastern bloc (Soviet Union and its allies). Morocco was the only African country in the region allied with the West (USA and its allies).

Algeria helped the Movimiento de Liberación del Sahara, which later became the Polisario. Most Sahrawi people supported this movement.

On November 14, 1975, Spain, Morocco, and Mauritania signed the Madrid Accords. This set a timeline for Spain to remove its forces and end its control of Western Sahara. In these agreements, Morocco was to take back two-thirds of the northern part of Western Sahara. The southern third would go to Mauritania. Polisario created their own Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. They fought using both guerrilla tactics and their regular army, the Sahrawi People's Liberation Army (SPLA).

On February 26, 1976, Spain officially ended its control over the territory. It handed over administrative power to Morocco in a ceremony in Laayoune. The next day, the Polisario announced the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) in Bir Lehlou. This was a government that existed outside the country. Mauritania renamed the southern parts of Río de Oro as Tiris al-Gharbiyya. However, Mauritania could not keep control of the territory. The Polisario focused its attacks on the weak Mauritanian army. After a bold raid on the Mauritanian capital, Nouakchott (where El-Ouali, the first president of the SADR, was killed), Mauritania faced internal unrest. Many Sahrawi nationalists among Mauritania's Moorish population made the government's position even weaker. Thousands of Mauritanian Sahrawis joined the Polisario. In 1978, the army took control of the Mauritanian government. The Polisario declared a cease-fire, believing Mauritania would leave without conditions. This happened in 1979, as Mauritania's new rulers agreed to give up all claims and recognize the SADR. However, after Mauritania left, Morocco extended its control to the rest of the territory, and the war continued.

Throughout the 1980s, the war reached a standstill because Morocco built a long sand wall, called the Moroccan Wall. Occasional fighting continued. Morocco faced heavy costs because of its many troops along the Wall. Aid from Saudi Arabia, France, and the USA helped Morocco, but the situation became difficult for everyone involved.

Cease-fire

In 1991, Morocco and the Polisario Front agreed to a UN-backed cease-fire as part of the Settlement Plan. This plan, further detailed in the 1997 Houston Agreement, depended on Morocco agreeing to a referendum (a vote) on whether the Sahrawi people wanted independence or to join Morocco. The plan aimed for this referendum to be their way of deciding their own future, completing the territory's unfinished process of becoming independent from colonial rule. The UN sent a peace-keeping mission, called MINURSO, to watch over the cease-fire and arrange the vote. The vote was first planned for 1992, but it has not happened because of disagreements over who has the right to vote.

Two later attempts to solve the problem through talks by James Baker, a special representative for the UN Secretary General, also failed. The first attempt in 2000 was rejected by the Polisario, and the second in 2003 was rejected by Morocco. Both plans suggested that the region would have some self-rule under Moroccan control. The UN Security Council did not officially support either plan, which led to Baker leaving his role.

The long cease-fire has mostly held without big problems. However, Polisario has often threatened to start fighting again if no solution is found. Morocco's decision in 2003 to withdraw from the original Settlement Plan and the Baker Plan talks left the peace-keeping mission without a clear political goal. This increased the risk of war starting again.

Meanwhile, political life in Morocco slowly became more open in the 1990s, and this reached Western Sahara around 2000. This led to protests. People who had been "disappeared" (taken by authorities and not seen again) and other human rights activists started holding illegal demonstrations against Moroccan rule. The crackdowns and arrests that followed brought media attention to the Moroccan control. Sahrawi nationalists used this chance. In May 2005, a wave of demonstrations, called the Independence Intifada by Polisario supporters, began. These protests, which continued into the next year, were the most intense in years. They created new interest in the conflict and new fears of instability. Polisario asked for international help but said it could not stand by if the "escalation of repression" continued.

In 2007, Morocco asked the U.N. to act against a meeting the Polisario Front planned to hold in Tifariti. Morocco claimed Tifariti was part of a buffer zone, and holding the meeting there broke the cease-fire. Also, the Polisario Front was reported to be planning a vote on preparing for war. If passed, it would have been the first time in 16 years that war preparations were part of Polisario's plan.

In October 2010, the Gadaym Izik camp was set up near Laayoune. This was a protest by displaced Sahrawi people about their living conditions. More than 12,000 people lived there. In November 2010, Moroccan security forces entered the Gadaym Izik camp early in the morning. They used helicopters and water cannons to make people leave. The Polisario Front said Moroccan security forces had killed a 26-year-old protester at the camp, but Morocco denied this. Protesters in Laayoune threw stones at police and set fire to tires and vehicles. Several buildings, including a TV station, were also set on fire. Moroccan officials said five security personnel had been killed in the unrest.

In 2020, the Polisario Front took legal action against New Zealand's superannuation fund. They claimed it was accepting "blood phosphate" from the occupied region. In November a short conflict broke out near the southern village of Guerguerat. Morocco claimed it wanted to end a blockade of a road to Mauritania and pave that road.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del Sahara Occidental para niños

In Spanish: Historia del Sahara Occidental para niños

- Ali Salem Tamek

- Almoravids

- Berlin Conference

- Brahim Dahane

- James Riley (Captain)

- João Fernandes (explorer)

- List of Spanish colonial wars in Morocco

- Mohamed Daddach

- Mohamed Elmoutaoikil

- Moroccan Liberation Army

- Saadi Dynasty

- Sahrawi (disambiguation)

- Scramble for Africa

- Spanish Morocco

- Spanish Sahara

- Western Saharan cuisine

- Years of Lead (Morocco)

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |