History of Morocco facts for kids

The history of people living in Morocco goes way back to the Stone Age, with the oldest human remains found at Jebel Irhoud. Much later, Morocco was home to the Iberomaurusian culture, including the people of Taforalt. Its story covers everything from the ancient Berber kingdoms like Mauretania to the start of the Moroccan state by the Idrisid dynasty and other Islamic rulers, all the way to the time when European countries took control, and then when Morocco became independent.

Scientists have found proof that early humans lived in this area at least 400,000 years ago. The written history of Morocco begins when the Phoenicians started setting up trading posts along the Moroccan coast between the 8th and 6th centuries BCE. However, local Berber people had lived there for about two thousand years before that. In the 5th century BCE, the powerful city-state of Carthage took control of these coastal areas. They stayed until the late 3rd century BCE, while local kings ruled the land further inland. Berber kings ruled the territory from the 3rd century BCE until 40 CE, when the Roman Empire took it over and called it Mauretania Tingitana. In the mid-5th century CE, the Vandals invaded, but the Byzantine Empire got it back in the 6th century.

The region was conquered by Muslims in the early 8th century CE. But it broke away from the big Umayyad Caliphate after the Berber Revolt in 740 CE. About 50 years later, the Moroccan state was officially created by the Idrisid dynasty. The Saadi dynasty ruled the country from 1549 to 1659. After them, the Alaouites took over in 1667 and have been the ruling family of Morocco ever since.

Contents

- Ancient Morocco: Early Humans and Kingdoms

- Early Islamic Morocco (c. 700 – c. 743)

- Morocco's First Dynasties

- Powerful Empires: Almoravids and Almohads

- Marinid Dynasty (c. 1244–1465)

- Wattasid Dynasty (c. 1472–1554)

- Saadi Dynasty (1549–1659)

- Republic of Salé (1624–1668)

- Alaouite Dynasty (since 1666)

- European Influence (c. 1830 – 1956)

- Independent Morocco (since 1956)

- See also

- Images for kids

Ancient Morocco: Early Humans and Kingdoms

Prehistoric Times

Archaeological digs show that very early humans, ancestors of Homo sapiens, lived in Morocco. Bones of an early human ancestor, 400,000 years old, were found in Salé in 1971. Even older bones of Homo sapiens were found at Jebel Irhoud in 1991. In 2017, modern tests showed these bones were at least 300,000 years old, making them the oldest Homo sapiens remains found anywhere! In 2007, small shell beads were found in Taforalt. These beads are 82,000 years old, making them the earliest known jewelry in the world.

During the Mesolithic period (20,000 to 5000 years ago), Morocco looked more like a savanna (grassy plains) than the dry land it is today. Not much is known about settlements from this time, but other digs in the Maghreb region suggest there was plenty of game and forests, making it a good place for Mesolithic hunters and gatherers.

In the Neolithic period, hunters and herders lived on the savanna. Their culture thrived until the region became drier after 5000 BCE due to climate changes. People living on the coast during the early Neolithic period used Cardium pottery, which was common around the Mediterranean. Digs suggest that people started raising cattle and growing crops in the region during this time. In the Chalcolithic period (Copper Age), the Beaker culture reached the northern coast of Morocco.

Carthage: A Trading Power (c. 800 – c. 300 BCE)

When the Phoenicians arrived on the Moroccan coast, it began many centuries of foreign rule in northern Morocco. Phoenician traders explored the western Mediterranean before the 8th century BCE. Soon after, they set up places to store salt and ore along the coast and up the rivers of what is now Morocco. Important early Phoenician settlements included Chellah, Lixus, and Mogador. We know Mogador was a Phoenician colony by the early 6th century BCE.

By the 5th century BCE, the state of Carthage had become very powerful across much of North Africa. Carthage traded with the Berber tribes living inland. They paid the Berbers a yearly tribute to make sure they cooperated in getting raw materials.

Mauretania: Berber Kings and Roman Rule (c. 300 BCE – c. 430 CE)

Mauretania was an independent kingdom of Berber tribes on the Mediterranean coast of North Africa. It covered the northern part of modern-day Morocco starting around the 3rd century BCE. The first known king of Mauretania was Bocchus I, who ruled from 110 BCE to 81 BCE. Some of its earliest history is linked to Phoenician and Carthaginian settlements like Lixus and Chellah. The Berber kings ruled the inland areas, often working with the coastal outposts of Carthage and Rome. Mauretania became a client state of the Roman Empire in 33 BCE. It became a full Roman province in 40 CE after Emperor Caligula had the last king, Ptolemy of Mauretania, killed.

Rome controlled this large territory by making agreements with the tribes, rather than by sending many soldiers. They only expanded their power to areas that were useful for trade or easy to defend. So, Roman rule never went beyond the northern coastal plains and valleys. This important region became part of the Roman Empire, known as Mauretania Tingitana, with the city of Volubilis as its capital.

During the time of the Roman emperor Augustus, Mauretania was a state that paid tribute to Rome. Its rulers, like Juba II, controlled all the areas south of Volubilis. But Roman soldiers only effectively controlled as far south as Sala Colonia. Some historians believe the Roman border reached present-day Casablanca, which was then known as Anfa and had been settled by the Romans as a port.

During Juba II's rule, Augustus founded three Roman settlements with Roman citizens near the Atlantic coast: Iulia Constantia Zilil, Iulia Valentia Banasa, and Iulia Campestris Babba. Augustus eventually founded twelve such settlements in the region. During this period, the area controlled by Rome grew economically, helped by the building of Roman roads. The area was not fully under Roman control at first. Only in the mid-2nd century was a defensive border, called a limes, built south of Sala extending to Volubilis. Around 278 CE, the Romans moved their regional capital to Tangier, and Volubilis became less important.

Christianity arrived in the region in the 2nd century CE. It gained followers in towns, among slaves, and among Berber farmers. By the end of the 4th century, the Romanized areas had become Christian. Some Berber tribes also converted in large numbers. Different Christian groups and ideas also appeared, often as a way to protest politically. The area also had a large Jewish population.

Early Islamic Morocco (c. 700 – c. 743)

Muslim Conquest

The Muslim conquest of the Maghreb, which started in the mid-7th century CE, was completed in the early 8th century. This brought both the Arabic language and Islam to the area. Although Morocco was part of the larger Islamic Empire, it was first set up as a smaller province of Ifriqiya. Local governors were appointed by the Muslim governor in Kairouan.

The local Berber tribes adopted Islam, but they kept their own traditional laws. They also paid taxes and tribute to the new Muslim government.

Berber Revolt (740–743)

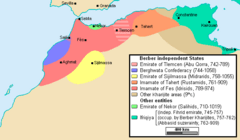

In 740 CE, encouraged by strict Kharijite religious leaders, the native Berber people rebelled against the ruling Umayyad Caliphate. The rebellion started among the Berber tribes in western Morocco and quickly spread across the region. Even though the uprising ended in 742 CE before reaching Kairouan, neither the Umayyad rulers nor their later Abbasid successors managed to take back control of the areas west of Ifriqiya. Morocco broke away from Umayyad and Abbasid control and split into several small, independent Berber states. These included Berghwata, Sijilmassa, and Nekor, as well as Tlemcen and Tahert in what is now western Algeria. The Berbers then developed their own versions of Islam. Some, like the Banu Ifran, stayed connected to radical Islamic groups, while others, like the Berghwata, created a new mixed faith.

Morocco's First Dynasties

After the Berber Revolt, several smaller states emerged. The Barghawatas, a group of Berber tribes, formed an independent state from 744 to 1058 along the Atlantic coast. The Midrarid dynasty founded the city of Sijilmasa in 757, which became a very important trading center for the trans-Saharan trade. The Kingdom of Nekor, an emirate in the Rif area, was founded in 710 CE and ruled by the Banū Sālih family until 1019.

Idrisid Dynasty (789–974)

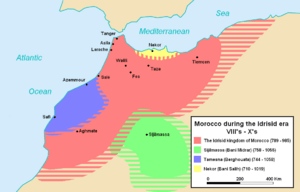

The Idrisid dynasty was a Muslim ruling family in Morocco from 788 to 974. It was named after its founder, Idriss I. Many historians believe the Idrisids were the first to establish a Moroccan state.

By the late 8th century, the western parts of the Maghreb, including modern-day Morocco, had become independent from the Umayyad Caliphate. This happened after the Khariji-led Berber Revolt in 739–740. The later Abbasid Caliphate also failed to regain control over Morocco. This meant Morocco was controlled by various local Berber tribes and small kingdoms, like the Barghwata Confederacy and the Midrarid Emirate in Sijilmasa.

The founder of the Idrisid dynasty was Idris ibn Abdallah (788–791). He was a great-grandchild of Hasan ibn Ali, who was the grandson of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad. After a battle near Mecca, Idris ibn Abdallah fled to the Maghreb. He first arrived in Tangier, then the most important city in Morocco. By 788, he had settled in Volubilis (known as Walili in Arabic).

The powerful Awraba Berbers of Volubilis welcomed Idris and made him their 'imam' (religious leader). The Awraba tribe was already Muslim, but they lived in an area where many tribes were Christian, Jewish, Khariji, or pagan. The Awraba likely saw Idris as a way to strengthen their political power. Idris I began by taking control and working to bring the Christian and Jewish tribes under his rule. In 789, he founded a new settlement southeast of Volubilis, called Medinat Fas. In 791, Idris I was poisoned and killed by an Abbasid agent. He had no male heir at the time, but shortly after his death, his wife, Lalla Kanza, gave birth to his only son and successor, Idris II. Idris's loyal companion, Rashid, raised the boy and acted as regent for the state. In 801, Rashid was killed by the Abbasids. The next year, at age 11, Idris II was declared imam by the Awraba.

Even though he had spread his power across much of northern Morocco, Idris I had relied completely on the Awraba leaders. Idris II started his rule by weakening the Awraba's power. He welcomed Arab settlers to Walili and appointed two Arabs as his chief minister and judge. This changed him from being protected by the Awraba to being their ruler. The Awraba leader, Ishak, responded by planning against him with the Aghlabids of Tunisia. Idris had Ishak killed. In 809, he moved his government from Walili to Fes, where he founded a new settlement called Al-'Aliya. Idris II (791–828) developed the city of Fez, which his father had started as a Berber market town. He welcomed two waves of Arab immigrants, giving Fez a more Arab feel than other cities in the Maghreb. When Idris II died in 828, the Idrisid state stretched from western Algeria to the Sous in southern Morocco. It had become the most important state in Morocco, ahead of the smaller kingdoms of Sijilmasa, Barghawata, and Nekor, which remained outside their control.

The dynasty's power slowly decreased after Idris II's death. Under his son and successor Muhammad (828–836), the kingdom was divided among seven of his brothers. This created eight smaller Idrisid states in Morocco and western Algeria. Muhammad himself ruled Fez, with only symbolic power over his brothers.

During this time, Islamic and Arabic culture became strong in the towns. Morocco benefited from the trans-Saharan trade, which was mostly controlled by Muslim (mostly Berber) traders. The city of Fez also grew and became an important religious center. More Arab immigrants arrived during Yahya I's rule, and the famous mosques of al-Qarawiyyin and al-Andalusiyyin were founded. However, Islamic and Arabic culture mostly influenced the towns. Most of Morocco's population still spoke Berber languages and often followed different Islamic beliefs. The Idrisids mainly ruled the towns and had little power over most of the country's people.

The Idrisid dynasty eventually faced challenges from other Berber tribes and the rising power of the Fatimid Caliphate from the east. By 974, the Idrisids were defeated, and their rule ended. Despite this, many families in Morocco today still claim to be descendants of the Idrisids. The tombs of Idris II in Fez and Idris I in Moulay Idriss Zerhoun became important religious sites.

Powerful Empires: Almoravids and Almohads

Almoravid Dynasty (c. 1060 – 1147)

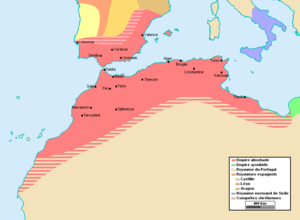

The Almoravid dynasty (around 1060–1147) started with the Lamtuna nomadic Berber tribe, part of the Sanhaja group. They managed to unite Morocco after it had been split among several smaller Berber kingdoms in the late 10th century. They also took over the Emirate of Sijilmasa and the Barghawata lands.

Under Yusuf ibn Tashfin, the Almoravids were asked by the Muslim princes of Al-Andalus (Spain) to protect their lands from Christian kingdoms. Their help was very important in stopping Al-Andalus from falling to the Christians. After pushing back Christian forces in 1086, Yusuf returned to Spain in 1090 and took control of most of the major Muslim states there.

Almoravid power began to weaken in the first half of the 12th century. This was due to their defeat at the battle of Ourique and the growing influence of the Almohads. The Almohads' capture of the city of Marrakech in 1147 marked the end of the Almoravid dynasty. However, some parts of the Almoravids continued to fight in the Balearic Islands and in Tunisia.

The Almoravids were known for their strong religious beliefs and their efforts to spread a strict form of Islam. They built many mosques and schools, and their rule brought a period of stability and growth to Morocco and parts of Spain.

Almohads (c. 1121–1269)

The Almohad Caliphate was a powerful North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its peak, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula (Muslim Spain, called Al Andalus) and North Africa (the Maghreb). The Almohad teachings were started by Ibn Tumart among the Berber Masmuda tribes in the Atlas Mountains of southern Morocco. At that time, Morocco, western Algeria, and Spain were ruled by the Almoravids, another Berber dynasty. Around 1120, Ibn Tumart first set up a Berber state in Tinmel in the Atlas Mountains.

Ibn Tumart believed in a very strict idea of God's unity (called tawhid). He thought that believing in separate attributes of God was wrong because it went against God being one. His followers became known as the al-Muwaḥḥidūn ("Almohads"), meaning "those who affirm the unity of God."

Around 1124, Ibn Tumart built a strong, fortified complex in Tinmel, which became the spiritual and military center of the Almohad movement. For the first eight years, the Almohad rebellion was a guerilla war in the mountains. In 1130, they attacked the lowlands for the first time. It was a disaster. They were badly defeated by the Almoravids in the Battle of al-Buhayra near Marrakesh, losing many leaders.

Ibn Tumart died shortly after, in August 1130. The movement didn't collapse thanks to his successor, Abd al-Mu'min. Ibn Tumart's death was kept secret for three years, giving Abd al-Mu'min time to become the new leader. Even though he was from a different Berber tribe, Abd al-Mu'min managed to unite the tribes and was officially declared "Caliph."

Almohad Conquests

Abd al-Mu'min then took charge. Between 1130 and his death in 1163, he not only defeated the Almoravids but also expanded his power across all of North Africa, reaching as far as Egypt. He became the ruler of Marrakesh in 1149.

Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain) followed the same path. Between 1146 and 1173, the Almohads slowly took control from the Almoravids over the Muslim states in Spain. The Almohads moved the capital of Muslim Spain from Córdoba to Seville. They built a great mosque there; its tower, the Giralda, was built in 1184 to mark the rule of Ya'qub I. They also built a palace called Al-Muwarak in Seville.

The Almohad rulers were more successful than the Almoravids. Abd al-Mu'min's successors, Abu Yaqub Yusuf (Yusuf I, ruled 1163–1184) and Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur (Yaʻqūb I, ruled 1184–1199), were both strong leaders. At first, their government caused many Jewish and Christian people to flee to the growing Christian states in Portugal, Castile, and Aragon. But later, they became less extreme. Ya'qub al-Mansur was a very educated man who wrote well in Arabic and protected the philosopher Averroes. He earned his title "al-Manṣūr" ("the Victorious") by defeating Alfonso VIII of Castile in the Battle of Alarcos (1195).

Decline and Fall

In 1212, the Almohad Caliph Muhammad 'al-Nasir' (1199–1214) was defeated by an alliance of four Christian kings at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in Spain. This battle broke the Almohad advance, but the Christian powers were too disorganized to take full advantage right away.

After al-Nasir's death in 1213, his young ten-year-old son, Yusuf II, became caliph. The Almohads then went through a period where older family members and officials ruled for the young caliph. They made peace agreements with the Christian kingdoms, which mostly lasted for the next fifteen years.

In 1224, the young caliph died in an accident without any heirs. This led to disagreements among the Almohad family, especially between those in Marrakesh and those ruling in Spain. This internal conflict weakened the Almohads greatly.

Reconquista in Spain

The departure of the Almohads from Spain in 1228 marked the end of their rule there. Local Muslim leaders in Spain were unable to stop the increasing Christian attacks. The next twenty years saw a huge advance in the Christian reconquista (reconquest). Major Muslim cities like Mérida, Badajoz, Majorca, Córdoba, Valencia, and finally Seville fell to Christian forces by 1248.

The Muslim people in Spain were helpless against these attacks. After the death of their leader Ibn Hud in 1238, some cities tried to ask the Almohads for help again, but it was too late. The Almohads would not return.

With the Almohads gone, the Nasrid dynasty rose to power in Granada. After the big Christian advances, the Emirate of Granada was almost all that was left of Muslim Spain. Granada remained independent for another 250 years, becoming a new center of Muslim culture in Spain.

Collapse in North Africa

In their African lands, the Almohads allowed Christians to settle even in Fez. After the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, they sometimes made alliances with Christian kings. They successfully removed the garrisons placed in some coastal towns by the Norman kings of Sicily. The Almohads didn't fall due to a single religious movement like the Almoravids did. Instead, they lost territories bit by bit as tribes and regions revolted. Their most effective enemies were the Banu Marin, who founded the next dynasty. The last Almohad ruler, Idris II, only controlled Marrakesh. He was murdered by a slave in 1269, ending the Almohad dynasty.

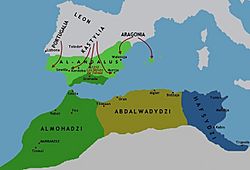

Marinid Dynasty (c. 1244–1465)

Although the Marinids claimed to be of Arab descent, they were actually from a Berber tribe. After Arab groups arrived in North Africa in the mid-11th century, the Marinids had to leave their lands near Biskra in modern-day Algeria. They moved seasonally between the Figuig oasis and the Moulouya River basin. By the early 13th century, they moved into Morocco in large numbers.

The Marinids took their name from their ancestor, Marin ibn Wartajan al-Zenati.

Rise to Power

When they first arrived in Morocco, they were under the rule of the Almohad dynasty. After helping in the Battle of Alarcos in Spain, the tribe started to become a political force. From 1213, they began taxing farmers in northeastern Morocco. Their relationship with the Almohads became tense, and fighting broke out regularly from 1215. In 1217, they tried to take the eastern part of Morocco but were pushed back, settling in the eastern Rif mountains for nearly 30 years. During this time, the Almohad state suffered greatly, losing large areas to Christians in Spain. Other regions like Ifriqia and Tlemcen also broke away.

Between 1244 and 1248, the Marinids were able to capture Taza, Rabat, Salé, Meknes, and Fez from the weakened Almohads. The Marinid leaders in Fez declared war on the Almohads, even using Christian soldiers. Abu Yusuf Yaqub (1259–1286) captured Marrakech in 1269, officially ending Almohad rule.

Golden Age

After the Nasrids of Granada gave the town of Algeciras to the Marinids, Abu Yusuf went to Al-Andalus to help in the fight against the Kingdom of Castile. The Marinid dynasty then tried to control the trade through the Strait of Gibraltar.

During this time, Spanish Christians tried to invade Morocco. In 1260 and 1267, they attempted invasions, but both were defeated. After gaining a foothold in Spain, the Marinids became active in the conflict between Muslims and Christians in Iberia. To fully control trade in the Strait of Gibraltar, they started conquering several Spanish towns from their base at Algeciras. By 1294, they had taken Rota, Tarifa, and Gibraltar.

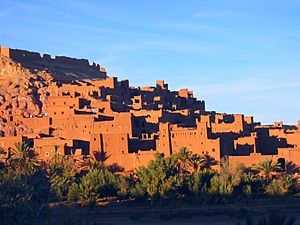

In 1276, they founded Fes Jdid (New Fez), making it their administrative and military center. While Fez was already a rich city during the Almohad period, it reached its golden age under the Marinids. Fez became known as an important intellectual center during this time. The Marinids built the first madrasas (religious schools) in the city and country. Many of the main buildings in the old city of Fez date from the Marinid period.

Despite internal conflicts, Abu Said Uthman II (ruled 1310–1331) started huge building projects across the land. Several madrasas were built, with the Al-Attarine Madrasa being the most famous. These schools helped create a group of educated officials loyal to the government.

The Marinids also had a strong influence on the politics of the Emirate of Granada. At the height of their power, under Abu al-Hasan Ali (ruled 1331–1348), the Marinid army was large and well-trained. It included 40,000 Berber cavalry, Arab nomads, and Spanish archers. The sultan's personal guard had 7,000 men, including Christian, Kurdish, and Black African soldiers. Under Abu al-Hasan, another attempt was made to unite the Maghreb. In 1337, the Abdalwadid kingdom of Tlemcen was conquered. In 1347, they defeated the Hafsid empire in Ifriqiya, making him ruler of a huge territory from southern Morocco to Tripoli. However, within the next year, a revolt by Arab tribes in southern Tunisia caused them to lose their eastern lands. The Marinids had also suffered a major defeat by a Portuguese-Castilian alliance in the Battle of Río Salado in 1340. They finally had to leave Spain, only holding onto Algeciras until 1344.

In 1348, Abu al-Hasan was removed from power by his son Abu Inan Faris, who tried to reconquer Algeria and Tunisia. Despite some successes, he was killed by his own chief minister in 1358. After this, the dynasty began to decline.

Decline

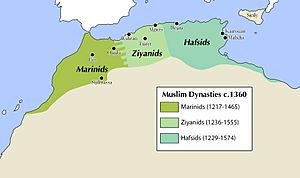

After Abu Inan Faris died in 1358, the real power was held by the chief ministers, while the Marinid sultans were changed quickly one after another. The country became divided and politically chaotic. Different ministers and foreign powers supported different groups. In 1359, tribesmen from the High Atlas took over Marrakesh, which they ruled independently until 1526. To the south of Marrakesh, Sufi religious leaders claimed independence. To the east, the Zianid and Hafsid families became powerful again. To the north, European countries took advantage of the instability by attacking the coast. Meanwhile, unruly nomadic Arab tribes caused more chaos, speeding up the empire's decline.

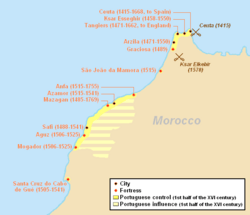

In the 15th century, a financial crisis hit. The government had to stop funding the religious leaders and noble families who had helped control the tribes. This caused political support to disappear, and the country split into many smaller parts. In 1399, Tetouan was captured and its people killed. In 1415, the Portuguese captured Ceuta. After Sultan Abdalhaqq II (1421–1465) tried to break the power of the Wattasids, he was executed.

Marinid rulers after 1420 were controlled by the Wattasid family, who acted as regents because Abd al-Haqq II became Sultan when he was only one year old. However, the Wattasids refused to give up their power when Abd al-Haqq grew up.

In 1459, Abd al-Haqq II managed to kill many members of the Wattasid family, breaking their power. But his rule ended violently when he was murdered during the 1465 revolt. This event marked the end of the Marinid dynasty. Muhammad ibn Ali Amrani-Joutey, a leader of the Sharifs, was declared Sultan in Fes. He was overthrown in 1471 by Abu Abd Allah al-Sheikh Muhammad ibn Yahya, one of the two Wattasids who survived the 1459 massacre. This began the Wattasid dynasty.

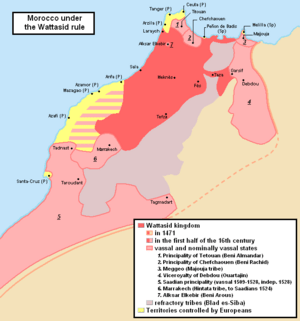

Wattasid Dynasty (c. 1472–1554)

Morocco was in decline when the Berber Wattasids took power. The Wattasid family had been independent governors of the eastern Rif since the late 13th century. They had close ties to the Marinid sultans and many of them were important government officials. While the Marinid dynasty tried to fight off Portuguese and Spanish invasions and help the kingdom of Granada survive the Reconquista, the Wattasids slowly gained complete power through clever political moves. When the Marinids realized how much power the Wattasids had gained, they killed many of them, leaving only Abu Abd Allah al-Sheikh Muhammad ibn Yahya alive. He went on to found the Kingdom of Fez and start the dynasty. His son, Mohammed al-Burtuqali, became ruler in 1504.

The Wattasid rulers failed to protect Morocco from foreign attacks, and the Portuguese increased their presence on Morocco's coast. Mohammad al-Chaykh's son tried to capture Asilah and Tangier in 1508, 1511, and 1515, but he was not successful.

In the south, a new dynasty, the Saadian dynasty, began to rise. They took Marrakesh in 1524 and made it their capital. By 1537, the Saadians were becoming very strong when they defeated the Portuguese Empire at Agadir. Their military successes were a big contrast to the Wattasid policy of trying to make peace with the Catholic kings to the north.

Because of this, the people of Morocco saw the Saadians as heroes. This made it easier for the Saadians to take back the Portuguese strongholds on the coast, including Tangiers, Ceuta, and Maziɣen. The Saadians also attacked the Wattasids, who were forced to give in to the new power. In 1554, as Wattasid towns surrendered, the Wattasid sultan, Ali Abu Hassun, briefly retook Fez. But the Saadians quickly ended this by killing him. As the last Wattasids fled Morocco by ship, they were also murdered by pirates.

The Wattasids did little to improve conditions in Morocco after the Reconquista. It took the Saadians to bring back order and stop the expansionist plans of the kingdoms in Spain and Portugal.

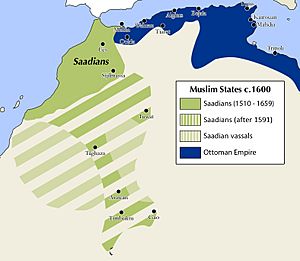

Saadi Dynasty (1549–1659)

Starting in 1549, the region was ruled by a series of Arab dynasties known as the Sharifian dynasties. These rulers claimed to be descendants of the prophet Muhammad. The first of these was the Saadi dynasty, which ruled Morocco from 1549 to 1659. From 1509 to 1549, the Saadi rulers only controlled the southern areas. While they still recognized the Wattasids as Sultans until 1528, the Saadians' growing power led the Wattasids to attack them. After a battle that didn't have a clear winner, the Wattasids recognized Saadian rule over southern Morocco through the Treaty of Tadla.

In 1590, Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur sent an army to the Songhai Empire in West Africa. This resulted in a victory and the collapse of the Songhai Empire. The Pashalik of Timbuktu was then set up to control the territory around Timbuktu.

In 1659, Mohammed al-Hajj ibn Abu Bakr al-Dila'i, the head of a religious center called the zaouia of Dila, was declared sultan of Morocco after the Saadi dynasty fell.

Republic of Salé (1624–1668)

The Republic of Salé started in the early 17th century. About 3,000 wealthy Moriscos (Muslims who had been forced to convert to Christianity in Spain) arrived from Spain. They expected the 1609 orders to expel Moriscos from Spain. After 1609, about 10,000 poorer expelled Moriscos also arrived. Because of cultural and language differences, the newcomers settled in the old part of Rabat, across the Bou Regreg river from Salé.

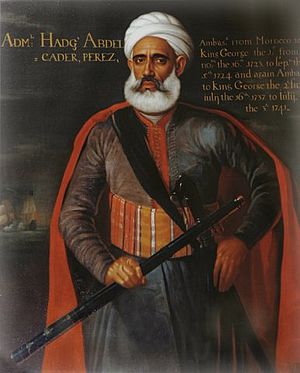

Pirates based on the western bank of the river became very successful. They expanded their operations across the Mediterranean and the Atlantic Ocean. In 1624, a Dutchman named Jan Janszoon (also known as Murad Reis) became the "Grand Admiral" and President of the Corsair Republic of Salé.

After Janszoon left Salé in 1627, the Moriscos stopped recognizing the authority of Sultan Zidan al-Nasir. They refused to pay his taxes on their earnings. They declared themselves a Republic, ruled by a council called a Diwan. This council had 12 to 14 important people who annually elected a Governor and a military leader. In the early years (1627-1630), the Diwan was controlled only by the Hornacheros Moriscos. This made other Moriscos, called Andalusians, unhappy. After bloody fights in 1630, they reached an agreement: the Andalusians would elect a Qaid, and the new Diwan would have 16 members, 8 from each group.

In 1641, the Zaouia of Dila, which controlled much of Morocco, took religious control over Salé and its republic. By the early 1660s, the republic was fighting a civil war with the zawiya. Eventually, Sultan Al-Rashid of Morocco of the Alaouite dynasty, which still rules Morocco today, seized Rabat and Salé, ending their independence. It came under the control of the Sultan of Morocco after 1668, when Moulay al Rashid finally defeated the Dilaites.

Alaouite Dynasty (since 1666)

The Alaouite dynasty is the current royal family of Morocco. The name Alaouite comes from ‘Alī of ‘Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib. His descendant Sharif ibn Ali became Prince of Tafilalt in 1631. His son Mulay Al-Rashid (1664–1672) was able to unite and bring peace to the country. The Alaouite family claims to be descendants of Muhammad through his daughter Fāṭimah az-Zahrah and her husband ‘Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib.

The kingdom became stronger under Ismail Ibn Sharif (1672–1727). He started to create a unified state despite opposition from local tribes. Since the Alaouites did not have the support of a single Berber or Bedouin tribe, unlike previous dynasties, Isma'īl controlled Morocco using an army of slaves. With these soldiers, he took back Tangiers in 1684 after the English left it. He also drove the Spanish from Larache in 1689. The kingdom he built did not last long after his death. In the power struggles that followed, the tribes became a political and military force again. It was only with Muhammad III (1757–1790) that the kingdom was united once more. The idea of a strong central government was put aside, and the tribes were allowed to keep their independence. On December 20, 1777, Morocco became one of the first countries to recognize the newly independent United States.

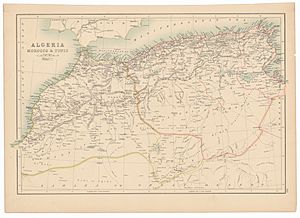

During the reigns of Muhammad IV (1859–1873) and Hassan I (1873–1894), the Alaouites tried to improve trade, especially with European countries and the United States. The army and government were also modernized to strengthen control over the Berber and Bedouin tribes. In 1859, Morocco went to war with Spain. Morocco's independence was guaranteed at the Conference of Madrid in 1880. France also gained significant influence over Morocco. Germany tried to stop the growing French influence, leading to the First Moroccan Crisis of 1905–1906 and the Second Moroccan Crisis of 1911. Morocco became a French protectorate through the Treaty of Fez in 1912.

European Influence (c. 1830 – 1956)

The successful efforts by Portugal to control the Atlantic coast in the 15th century did not affect the interior of Morocco. After the Napoleonic Wars, North Africa became harder for the Ottoman Empire to control from Istanbul. As a result, it became a place where pirates operated under local leaders. The Maghreb also had more known wealth than the rest of Africa, and its location near the entrance to the Mediterranean made it strategically important. France showed a strong interest in Morocco as early as 1830. The Alaouite dynasty managed to keep Morocco independent in the 18th and 19th centuries, despite attempts by the Ottoman Empire and European powers to take control.

In 1844, after the French conquered Algeria, the Franco-Moroccan War took place. This involved the bombardment of Tangiers, the Battle of Isly, and the bombardment of Mogador.

In 1856, Sultan Abd al-Rahman's government signed the Anglo-Moroccan treaty with British diplomat John Hay Drummond Hay. The treaty gave British citizens several rights in Morocco and lowered Moroccan customs taxes to 10%. This treaty helped Morocco stay independent but also opened the country to foreign trade, which reduced the government's control over the Moroccan economy.

The Hispano-Moroccan War took place from 1859 to 1860. The later Treaty of Wad Ras forced the Moroccan government to take a huge British loan, larger than its national savings, to pay off its war debt to Spain.

In the mid-19th century, Moroccan Jews began moving from inland areas to coastal cities like Essaouira, Mazagan, Asfi, and later Casablanca. They sought economic opportunities, trading with Europeans and helping these cities grow. The Alliance Israélite Universelle opened its first school in Tetuan in 1862.

In the late 19th century, Morocco's instability led European countries to step in to protect their investments and demand economic benefits. Sultan Hassan I called for the Madrid Conference of 1880 to address France and Spain's misuse of the protégé system. However, the result was an increased European presence in Morocco, including advisors, doctors, businessmen, and even missionaries.

More than half of the Moroccan government's spending went abroad to pay war debts and buy weapons, military equipment, and manufactured goods. From 1902 to 1909, Morocco's trade deficit grew by 14 million francs annually, and the Moroccan currency lost 25% of its value from 1896 to 1906. In June 1904, after a failed attempt to impose a flat tax, France helped the already indebted Moroccan government with 62.5 million francs, guaranteed by a portion of customs revenue.

In the 1890s, the French government and military in Algiers wanted to take over the Touat, Gourara, and Tidikelt regions. These areas had been part of the Moroccan Empire for many centuries before the French arrived in Algeria. The early 20th century saw major diplomatic efforts by European powers, especially France, to further their interests in the region.

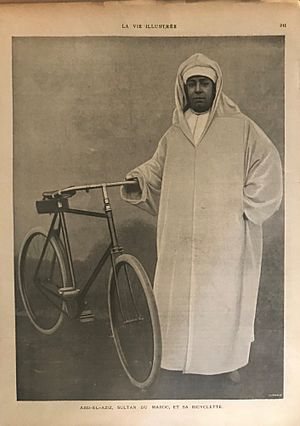

Morocco was officially ruled by its young sultan, Abd al-Aziz, through his regent, Ba Ahmed. By 1900, Morocco was experiencing many local wars started by people claiming to be sultan, the government was bankrupt, and there were many tribal revolts. The French Foreign Minister Théophile Delcassé saw this as a chance to stabilize the situation and expand the French empire overseas.

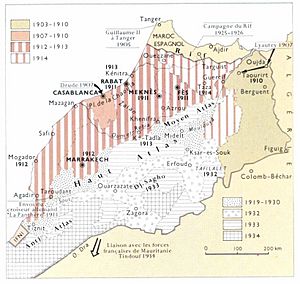

General Hubert Lyautey wanted a more aggressive military policy using his French army based in Algeria. France decided to use both diplomacy and military force. The French colonial authorities would take control over the Sultan, ruling in his name and extending French influence. The British agreed to French plans in Morocco in the Entente Cordiale of 1904. However, the Germans, who had no strong presence in the region, strongly protested against the French plan. The Kaiser's dramatic intervention in Morocco in March 1905 in support of Moroccan independence became a key moment leading to the First World War. The international Algeciras Conference of 1906 formally recognized France's "special position" and gave policing of Morocco jointly to France and Spain. Germany was outmaneuvered diplomatically, and France took full control of Morocco.

Morocco suffered a famine from 1903 to 1907. There were also rebellions led by El-Rogui and Mulai Ahmed er Raisuni.

French and Spanish Protectorate (1912–1956)

Hafidiya

In 1907, the French used the murder of Émile Mauchamp in Marrakesh as an excuse to invade Oujda in the east. They also used an uprising against their taking of customs revenue in Casablanca as a chance to bombard and invade that city in the west. Months later, there was a brief civil war called the Hafidiya. In this war, Abd al-Hafid, supported by southern nobles and later by religious scholars from Fez, took the throne from his brother Abd al-Aziz, who was supported by the French.

The Agadir Crisis increased tensions among powerful European countries. It led to the Treaty of Fez (signed on March 30, 1912), which made Morocco a protectorate of France. A second treaty signed by French and Spanish leaders gave Spain a zone of influence in northern and southern Morocco on November 27, 1912. The northern part became the Spanish protectorate in Morocco, while the southern part was ruled from El Aaiun as a buffer zone between the Spanish Colony of Saguia El Hamra and Morocco. The Treaty of Fez caused the 1912 Fez riots. By the Tangier Protocol signed in December 1923, Tangier received special status and became an international zone. However, during World War II, it was occupied from 1940 to 1945 by Francoist Spain.

-

Uprisings in Casablanca in July 1907 over the rules of the Treaty of Algeciras led to the Bombardment of Casablanca.

The treaties officially said Morocco was a sovereign state with the sultan as its leader. But in reality, the sultan had no real power. The country was ruled by the colonial government. French officials worked with French settlers and their supporters in France to stop any moves towards Moroccan independence. As "pacification" (military control) continued, with the Zaian War and the War of the Rif, the French government focused on taking Morocco's mineral wealth, especially its phosphates. They also built a modern transportation system with trains and buses, and developed modern farming for the French market. Tens of thousands of colons, or colonists, came to Morocco and bought large areas of rich farmland.

Morocco was home to half a million Europeans, most of whom settled in Casablanca, where they made up almost half the population. Since Morocco gained independence in 1956, and especially after Hassan II's 1973 Moroccanization policies, most of the European population has left.

The Spanish coup of July 1936, which started the Spanish Civil War, began with the Spanish army in Spanish occupied Morocco.

Opposition to European Control

Led by Abd el-Krim, the independent Republic of the Rif existed from 1921 to 1926. It was based in the central part of the Rif (in the Spanish Protectorate). For some months, it also spread to parts of the lands of the Ghomara, the Eastern Rif, Jbala, the Ouergha valley, and northern Taza. After declaring independence on September 18, 1921, the republic developed government systems like tax collection, law enforcement, and an army. However, by 1925, Spanish and French troops managed to stop the resistance, and Abd el-Krim surrendered in May 1926.

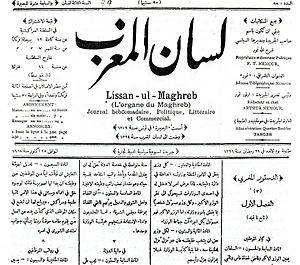

In December 1934, a small group of nationalists, members of the new Comité d'Action Marocaine (CAM), proposed a Plan of Reforms. This plan called for a return to indirect rule as intended by the Treaty of Fez, allowing Moroccans into government jobs, and setting up representative councils. CAM used petitions, newspaper articles, and personal appeals to French officials, but these were not enough. Tensions within CAM caused it to split. CAM was then reformed as a nationalist political party to gain public support for more radical demands, but the French suppressed the party in 1937.

Nationalist political parties, which later appeared under the French protectorate, based their arguments for Moroccan independence on statements like the Atlantic Charter. This was a joint United States-British statement that said, among other things, that all people have the right to choose their own government. The French government also faced opposition from the tribes. When the Berber people were required to come under the authority of French courts in 1930, it increased support for the independence movement.

Many Moroccan Goumiers, who were local soldiers in the French army, helped the Allies in both World War I and World War II. During World War II, the divided nationalist movement became more unified. However, the nationalists' belief that an Allied victory would lead to independence was disappointed. In January 1944, the Istiqlal (Independence) Party, which later provided most of the nationalist leaders, released a manifesto demanding full independence, national unity, and a democratic constitution. Sultan Muhammad V (1927–1961) had approved the manifesto before it was given to the French resident general, who replied that no major change to the protectorate status was being considered. The sultan's general sympathy for the nationalists became clear by the end of the war, although he still hoped for complete independence to be achieved slowly. On April 10, 1947, despite a massacre started by French forces in Casablanca, Sultan Muhammad V gave an important speech in Tangier calling for Morocco's independence and territorial unity. He had traveled from French Morocco and through Spanish Morocco to reach the Tangier International Zone. The French authorities, supported by French businesses and most of the colonists, strongly refused to consider even small reforms, let alone independence.

In December 1952, a riot broke out in Casablanca over the assassination of the Tunisian labor leader Farhat Hached. This event marked a turning point in relations between Moroccan political parties and French authorities. After the rioting, the French outlawed the new Moroccan Communist Party and the Istiqlal Party.

France's decision to send the highly respected Sultan Mohammed V to Madagascar in 1953, and replace him with the unpopular Mohammed Ben Aarafa, sparked strong opposition to the French protectorate. This opposition came from both nationalists and those who saw the sultan as a religious leader. In response, Muhammad Zarqtuni bombed Casablanca's Marché Central in the European part of the city on Christmas of that year. A month after his replacement, a Moroccan nationalist tried to assassinate the sultan on his way to Friday prayers. Two years later, facing a united Moroccan demand for the sultan's return and increasing violence in Morocco, as well as a worsening situation in Algeria, the French government brought Mohammed V back to Morocco. The following year, negotiations began that led to Moroccan independence. So, with the triumphant return of Sultan Mohammed ben Youssef, the end of the colonial era began.

Independent Morocco (since 1956)

In late 1955, during what became known as the Revolution of the King and the People, Sultan Mohammed V successfully negotiated the gradual return of Moroccan independence. This was done within a framework of French-Moroccan cooperation. The sultan agreed to make reforms that would turn Morocco into a constitutional monarchy with a democratic government. As the French Foreign Minister Antoine Pinay said, there was a willingness to grant Morocco its independence to "turn Morocco into a modern, democratic and sovereign state." In February 1956, Morocco gained limited self-rule. Further negotiations for full independence ended with the French-Moroccan Agreement signed in Paris on March 22, 1956.

On April 7, 1956, France officially gave up its protectorate in Morocco. The international city of Tangier was brought back into Morocco with the signing of the Tangier Protocol on October 29, 1956. The end of the Spanish protectorate and Spain's recognition of Moroccan independence were negotiated separately and finalized in April 1956. Through this agreement with Spain in 1956 and another in 1958, Morocco regained control over certain Spanish-ruled areas. Attempts to claim other Spanish possessions through military action were less successful.

In the months after independence, Mohammed V began to build a modern government structure under a constitutional monarchy. In this system, the sultan would play an active political role. He acted carefully, aiming to prevent the Istiqlal party from gaining too much control and creating a one-party state. He became the official monarch on August 11, 1957. From that date, the country was officially known as 'The Kingdom of Morocco'.

Reign of Hassan II (1961–1999)

Mohammed V's son Hassan II became King of Morocco on March 3, 1961. His rule saw significant political unrest. The government's harsh response to this unrest earned the period the name "the years of lead." Hassan took personal control of the government as prime minister and appointed a new cabinet. With the help of an advisory council, he wrote a new constitution, which was overwhelmingly approved in a December 1962 vote. Under this constitution, the king remained the central figure in the executive branch of the government. However, law-making power was given to a two-chamber parliament, and an independent court system was guaranteed.

In May 1963, legislative elections were held for the first time. The royalist group won a small majority of seats. However, after a period of political trouble in June 1965, Hassan II took full law-making and executive powers under a "state of exception," which lasted until 1970. Later, a new constitution was approved, bringing back limited parliamentary government, and new elections were held. However, people continued to complain about widespread corruption and wrongdoing in the government. In July 1971 and again in August 1972, the government faced two attempted military coups.

After neighboring Algeria gained independence from France in 1962, border clashes in the Tindouf area of southwestern Algeria grew into what is known as the Sand War in 1963. The conflict ended after mediation by the Organisation of African Unity, with no changes to the territory.

On March 3, 1973, Hassan II announced the policy of Moroccanization. This policy transferred government-owned assets, farmland, and businesses that were more than 50 percent foreign-owned (especially French-owned) to people loyal to the king and high-ranking military officers. The Moroccanization of the economy affected thousands of businesses. The percentage of industrial businesses in Morocco owned by Moroccans immediately increased from 18% to 55%. Two-thirds of the wealth from the Moroccanized economy was concentrated in 36 Moroccan families.

The strong national pride created by Morocco's involvement in the Middle East conflict and Western Sahara events helped Hassan's popularity. The king sent Moroccan troops to the Sinai front after the Arab-Israeli War began in October 1973. Although they arrived too late to fight, this action earned Morocco goodwill among other Arab states. Soon after, the government focused on taking Western Sahara from Spain, an issue that all major political parties in Morocco agreed on.

After years of unhappiness and inequality during the 1980s, a general strike was called on December 14, 1990, by two major trade unions. They demanded an increase in the minimum wage and other measures. In Fez, this turned into protests and riots led by university students and young people. The death of one student made the protests worse, leading to buildings being burned and looted, especially symbols of wealth. While the official death toll was 5 people, the New York Times reported 33 deaths and quoted an anonymous source claiming the real number was likely higher. The government denied reports that the deaths were caused by security forces. Many of those arrested were later released, and the government promised to investigate and raise wages, though some opposition parties were doubtful.

Western Sahara Conflict (1974–1991)

The Spanish enclave of Ifni in the south became part of Morocco in 1969. However, other Spanish possessions in the north, including Ceuta, Melilla, and Plaza de soberanía, remained under Spanish control. Morocco views these as occupied territory.

In August 1974, Spain officially recognized the 1966 United Nations (UN) resolution. This resolution called for a vote on the future of Western Sahara and asked for a plebiscite (a direct vote by the people) to be held under UN supervision. A UN visiting mission reported in October 1975 that most Saharan people wanted independence. Morocco protested the proposed vote and took its case to the International Court of Justice at The Hague. The court ruled that despite historical "ties of allegiance" between Morocco and the tribes of Western Sahara, there was no legal reason to go against the UN's position on self-determination. Meanwhile, Spain announced that it intended to give up political control of Western Sahara, even without a vote. Spain, Morocco, and Mauritania held a three-party conference to decide the territory's future. Spain also announced it was starting independence talks with the Algerian-backed Saharan independence movement known as the Polisario Front.

In early 1976, Spain gave the administration of Western Sahara to Morocco and Mauritania. Morocco took control over the northern two-thirds of the territory and gave the remaining southern portion to Mauritania. An assembly of Saharan tribal leaders then recognized Moroccan rule. However, encouraged by more tribal chiefs joining its side, the Polisario wrote a constitution and announced the formation of the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). They also formed a government-in-exile.

The Moroccan government eventually sent a large part of its army into Western Sahara to fight the Polisario's forces. The Polisario forces were relatively small but well-equipped, very mobile, and clever. The Polisario used bases in Algeria for quick attacks deep inside Morocco and Mauritania, as well as for operations in Western Sahara. In August 1979, after suffering military losses, Mauritania gave up its claim to Western Sahara and signed a peace treaty with the Polisario. In 1984, Morocco left the Organisation of African Unity because the SADR was admitted as a member. Morocco then took over the entire territory. In 1985, it built a 2,500-kilometer sand wall around three-quarters of Western Sahara.

In 1988, Morocco and the Polisario Front agreed on a United Nations (UN) peace plan. A cease-fire and settlement plan went into effect in 1991. Even though the UN Security Council created a peacekeeping force to hold a vote on self-determination for Western Sahara, it has not happened yet. Regular negotiations have failed, and the status of the territory remains undecided.

The war against the Polisario fighters put a severe strain on the economy. Morocco also found itself increasingly isolated diplomatically. Gradual political reforms in the 1990s led to the constitutional reform of 1996. This created a new two-chamber parliament with more, but still limited, powers. Elections for the Chamber of Representatives were held in 1997, though there were reports of problems.

Reign of Mohammed VI (since 1999)

When King Hassan II of Morocco died in 1999, the more liberal Crown Prince Sidi Mohammed took the throne, becoming Mohammed VI. He started many reforms to modernize Morocco, and the country's human-rights record greatly improved. One of the new king's first actions was to free about 8,000 political prisoners and reduce the sentences of another 30,000. He also set up a commission to pay families of missing political activists and others who had been unfairly held. In 1999, the First Sahrawi Intifada (uprising) took place. Internationally, Morocco has kept strong ties to Western countries. It was one of the first Arab and Islamic states to condemn the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States.

In September 2002, new parliamentary elections were held. The Socialist Union of Popular Forces (USFP) won the most seats. International observers considered the elections fair, noting that the problems from the 1997 elections were gone. In May 2003, to celebrate the birth of his son, the king ordered the release of 9,000 prisoners and reduced 38,000 sentences. Also in 2003, Berber-language teaching was introduced in primary schools, before being brought to all education levels. In March 2000, women's groups organized protests in Rabat. They proposed reforms to the legal status of women in the country. Between 200,000 and 300,000 women attended, calling for a ban on polygamy and the introduction of civil divorce law. Although a counter-protest attracted 200,000 to 400,000 participants, the movement influenced King Mohammed. He enacted a new Mudawana, or family law, in early 2004, meeting some of the demands of women's rights activists.

In July 2002, a crisis broke out with Spain over a small, uninhabited island less than 200 meters from the Moroccan coast. Moroccans call it Toura or Leila, and Spain calls it Perejil. After the United States helped mediate, both Morocco and Spain agreed to return to the previous situation, where the island remains empty.

In May 2003, Islamist terrorists simultaneously attacked several places in Casablanca. They killed 45 people and injured more than 100 others. The Moroccan government responded by cracking down on Islamist extremists, arresting several thousand, prosecuting 1,200, and sentencing about 900. More arrests followed in June 2004. That same month, the United States named Morocco a major non-North Atlantic Treaty Organization ally. This was in recognition of its efforts to stop international terrorism. In May 2005, the Second Sahrawi Intifada (uprising) took place. On January 1, 2006, a full free trade agreement between the United States and Morocco took effect. The agreement had been signed in 2004, along with a similar agreement with the European Union, Morocco's main trading partner.

In February 2011, thousands of people gathered in Rabat and other cities. They called for political reform and a new constitution that would limit the king's powers. Two months later, a bombing in Marrakesh killed 17 people, mostly foreigners. It was the deadliest attack in Morocco in eight years. The Maghrebi branch of al-Qaeda denied being involved. In July 2011, King Mohammed introduced a constitutional referendum to calm the "Arab Spring" protests. In article 5 of the 2011 constitution, Amazigh (Berber language) was recognized as an official language.

The 2016 election saw the Justice and Development Party win, becoming Morocco's leading party for the second time in a row.

In October 2016, large protests started after a fish seller in al-Hoceima was crushed to death in a rubbish truck while trying to get back fish confiscated by police. These protests became known as the Hirak Rif Movement. On January 30, 2017, Morocco rejoined the African Union as a member state, 33 years after leaving. The 2018 consumer boycott targeted major brands of fuel, bottled water, and dairy products. The worldwide COVID-19 pandemic arrived in Morocco, with the first case confirmed on March 2, 2020. Eight days later, on March 10, 2020, Morocco recorded its first COVID-19-related death. On December 10, 2020, President Donald Trump announced that the United States would officially recognize Morocco's claims over Western Sahara as part of the Israel–Morocco normalization agreement. On May 17, 2021, an incident occurred between the borders of Spain and Morocco, leading to a diplomatic crisis between the two nations. The 2021 election was held on September 8, 2021. This election saw a historic defeat for the Islamists (PJD), who lost more than 90% of their seats and placed eighth after winning the three previous elections. The election was won by the National Rally of Independents. Aziz Akhannouch was later named the 17th Prime Minister of Morocco. On June 24, 2022, a migration incident resulted in the death of 23 migrants. On May 3, 2023, King Mohammed VI declared Amazigh New Year an official national holiday to be celebrated every year.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Marruecos para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Marruecos para niños

- History of North Africa

- Imperial cities of Morocco

- List of Kings of Morocco

- Politics of Morocco

- History of cities in Morocco:

- Timeline of Morocco

Images for kids

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |