History of chocolate in Spain facts for kids

The history of chocolate in Spain is a fascinating part of Spanish food history. It all began in the 1500s when Spain started exploring the Americas. That's when they found the cocoa plant in places like Mesoamerica (modern-day Mexico and Central America). After Spain took over Mexico, cocoa beans started traveling by ship from the Americas to Spain. The first trip to Europe happened around the 1520s. But it was in the 1600s that regular trade began from the port of Veracruz. This opened up a sea route that brought cocoa to Spain and later to other European countries.

Unlike other new foods from the Americas, chocolate quickly became popular in Spain. Its popularity grew fast, reaching its peak by the late 1500s. Even though other European countries didn't adopt chocolate right away, it eventually became a very valuable product. Once Europeans realized how special chocolate was, they started to include it more in their daily lives.

From the very beginning, the Spanish sweetened cocoa with sugar cane. The Spanish were the first to make sugar cane popular in Europe. Before Columbus arrived in America, chocolate was often flavored with peppers. It was a mix of bitter and spicy tastes. This made it an acquired taste for the Spanish explorers. They soon started adding sugar from the Iberian Peninsula and heating it up.

About 100 years after it first arrived in Spain, chocolate became a popular drink. It was even served to the Spanish royal family. For a while, the secret recipe was unknown in the rest of Europe. Later, chocolate spread from Spain to other parts of Europe, with Italy and France being the first to adopt it.

Many travelers who visited Spain from the 1600s to the 1800s wrote about how much the Spanish loved chocolate. They often said, "chocolate is to the Spanish what tea is to the English." This shows how chocolate became a national symbol. Because of this strong love for chocolate, coffee was not as popular in Spain compared to other European countries.

In Spain, chocolate was mostly enjoyed as a warm drink. It was rarely used in other ways, though some older Spanish dishes did use cocoa. After the Spanish Civil War, drinking chocolate became less common as coffee grew more popular. Today, you can still see the history of chocolate in Spain in its chocolate companies, shops, and museums. The Spanish also mixed their sweetened chocolate drink with milk, just like coffee is mixed with milk. Sometimes, they also served chocolate as natural candy drops or "clusters." These form naturally because of the high cocoa butter content.

Contents

Ancient History of Chocolate

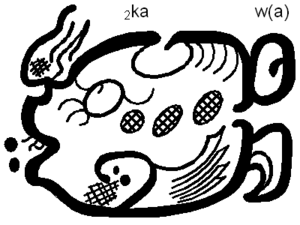

The cacao tree, which scientists call Theobroma cacao, comes from Mesoamerica. Some experts think it might have also grown in the Amazon basin or the Orinoco area. It's very likely that the Olmec people knew about the cacao plant around 1000 BC. They probably passed on its use and how to grow it to the Mayans. The Mayans were the first to write about cocoa in their hieroglyphics. There is proof that this drink was common among the noble classes.

Cocoa as Money

Spanish explorers wrote many times about how the Aztecs used cocoa beans as a type of currency. They had a special system for counting them. For example, a "countles" was four cocoa beans. A "xiquipil" was twenty "countles." A "burden" was three "xiquipiles." Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés wrote in 1535:

In Nicaragua, a Rabbit was worth ten kernels. For four kernels, they gave eight apples or a fruit called munonzapot. A slave was worth about 100 kernels, depending on the deal.

Cocoa was also important in other ways. It was used in religious ceremonies, weddings, and as medicine. Sometimes it was mixed with other plants. It was also a nutritious food. Many believed it was "a gift from the gods." This made it a symbol of wealth in ancient societies. It was mostly used as money to pay taxes to powerful rulers.

Chocolate's Journey to Spain

When the Spanish first found cocoa, they had to learn about it. First, they saw it as a food. Later, they learned to enjoy its taste. This happened by changing it to taste more like foods they already knew. Early Spanish explorers changed how cocoa was prepared. They sweetened it and added spices like cinnamon. They also served it warm. These three simple changes made the chocolate enjoyed by the Spanish different from the chocolate the native people drank. This pattern happened with other foods too, but none became as popular worldwide as chocolate.

Columbus' First Look

The explorer Christopher Columbus reached the Americas on October 12, 1492. He thought he had arrived in India. His trip was supported by the Spanish rulers to find new trade routes. This would help Spain compete with Portugal. After his first successful trip, more voyages were planned. On his fourth trip in 1502, Columbus faced a storm. He had to land on the Bay Islands on August 15. While exploring, Columbus' group found a Mayan boat from the Yucatán Peninsula. The Spanish were surprised by how big the boat was. Columbus stopped the boat and checked its cargo. It had cocoa beans, which he called almonds in his diary. But he didn't think they were important. After looking, he let the boat go on its way.

Later, from 1517 to 1519, Spanish explorers Bernal Díaz del Castillo and Hernán Cortés tried the chocolate drink. They found it tasted bitter and spicy because of achiote. Sometimes, cornmeal and mushrooms were also added. The Spanish then learned that cocoa beans were used as money by the local people. Toribio de Benavente, also known as Motolinía, wrote about cocoa in his books.

Encounters in New Spain

After Spain conquered Mexico, the Aztec emperor, Montezuma, offered Hernán Cortés and his friends fifty jars of foamy chocolate. According to Francisco Cervantes de Salazar, the emperor had thousands of cocoa "kernels" stored.

The Italian Girolamo Benzoni wrote in 1565 that chocolate "seemed more like a drink for pigs than a drink for humans." He said he never tasted it, even though he lived there for over a year. José de Acosta also disliked the drink, comparing its foamy top to waste.

The Spanish views on food slowly changed. They started to rely more on local ingredients. Foods like tortillas made with cornmeal or tamales were heated without fat. This didn't appeal to the Spanish, who were used to pork and cooking with lots of olive oil or bacon. Foods popular in Spain, like cheese, were unknown in the Americas.

As the Spanish settlers ran out of their own food, they had to find new things to eat. They began to plant vegetables like chickpeas, cereals like wheat, and fruits like oranges or pears. They also started growing olives, grapes, and sugar cane. Sugar cane became very important. By the late 1500s, sugar cane was added to cocoa paste. This made cocoa much more popular among the Spanish settlers.

During this time, around the 1520s, the Spanish had to get used to new foods and flavors. They also tried to grow their old crops in the new climate. But the native people also struggled to accept new ingredients like wheat and chickpeas. They preferred their own traditional dishes.

Spanish men from poorer families often married richer Aztec women, sometimes as second wives. This meant they ate food influenced by Aztec cuisine. This helped cocoa spread faster between both cultures. Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote that at a big party in Mexico City, chocolate was served in golden tablets. The wide acceptance of cocoa by the Spanish, especially women, was also described by the Jesuit José de Acosta in his book from 1590.

The Spanish accepted chocolate because they changed the drink. For example, sugar was added, just like native Mexicans and Mayans added honey to cocoa drinks. New World spices were replaced with similar spices from Europe. This was for familiarity and convenience. Cocoa drinks with corn, like atole, slowly disappeared. This was because chocolate without corn lasted longer, making it better for trips across the Atlantic. These changes helped the Spanish overcome their first dislike of cocoa.

After the initial dislike for cocoa faded, supplies were sent to Spain. The second big change the Spanish made was how chocolate was served. They heated the cocoa until it became a liquid. This was different from the native people, who usually drank it cold or at room temperature. The third change was adding spices from Europe like cinnamon, ground black pepper, or aniseed.

Naming the New Product

The Aztec language, Nahuatl, was hard for the Spanish soldiers in Mexico to say. While some sounds were similar to Spanish, the way Nahuatl words were put together was very different. One sound, "tl," was especially difficult. Spaniards often changed it to "te." For example, Hernán Cortés wrote "Temistitan" instead of Tenochtitlan. Living together, the two cultures shared words. The Spanish language borrowed words like coyote or maiz.

Many dictionaries say the word chocolate comes from the Nahuatl word chocolatl. But there are problems with this idea. First, some experts say the word chocolatl doesn't appear in Aztec writings from that time. Also, the word isn't in a grammar book of the Aztec language from 1555 by Alonso de Molina. It's also missing from other important Aztec works. In all these works, the word cacahuatl (cocoa water) is used. Hernán Cortés himself just called it 'cocoa' in his letters. At some point in the 1500s, the Spanish in Mexico started using the word chocolatl.

The royal doctor, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, knew this name in the 1570s. He described chocolatl as a drink made of ground cocoa beans and pochotl seeds. José de Acosta and others also used the name chocolatl in Nueva España and the Yucatán. This made the word a new term. But others think chocolatl came from xocoatl, where xoco means bitter and atl means water. Another idea comes from the Spanish habit of making hot cocoa. Many Mayan dictionaries from that time say "the drink called chocolate" comes from chacau haa (meaning 'hot water'). This sounds similar to chocolatl.

First Shipments to Spain

In 1520, Spanish ships called caravels began bringing cocoa to Spain. Sometimes, pirates from England would capture these ships. They didn't know what cocoa was, so they often burned or threw away the valuable cargo. No one knows exactly when cocoa first arrived in Spain. But by the mid-1500s, it was seen as a very valuable item. The strong Spanish galleons that carried the first cocoa seeds to Spanish ports show how valuable it was. They needed protection to prevent theft.

There's no proof that Hernán Cortés himself brought cocoa back to Spain. When he met King Charles I in 1528, cocoa was not listed among the gifts he brought from the Americas. The first cocoa shipments to Spain were made by small galleys. They used the "Chocolate wind," which was a helpful North wind in the Gulf of Mexico.

The first written record of chocolate in Spain is from 1544. A group of Dominican friars, led by Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, visited Prince Philip. They brought gifts of sweetgum, corn, and cocoa. It also mentions a chocolate milkshake that was served. This is the first recorded time chocolate was present in Spain. The Dominican friars knew about this food. This might have helped cocoa spread from monasteries in Mesoamerica to Spain. Studies suggest that Father Aguilar was the first in Spain to prepare chocolate for the Abbot of the Piedra Monastery.

Other writers say that Benedictine monks were the first to bring chocolate in 1532. The first shipments arrived by the Maria del Mar galley through the port of Cadiz. They were delivered to a convent in Seville. A quote from the Benedictines at the time said: "Do not drink the cocoa, anyone but friar, sir or brave soldier." In 1585, a group from Japan visited King Philip II. They were impressed by the chocolate offered by a nearby convent. From the start, Spanish priests were chocolate experts who shared their recipes. In 1601, a confessor in Cordoba added small amounts of chocolate to vegetables.

People tried to grow cocoa in Spain, but it failed completely. They realized that cocoa trees grow best in warm areas, between 20 degrees north and 20 degrees south of the equator. The need to find good climates for new foods meant that cocoa trees grew well in Fernando Poo (in Spanish Guinea). From there, they spread across Africa. At that time, pharmacists often made sweets and candies. They used chocolate in secret recipes and medicines. People debated if chocolate was good for nutrition. Possible medical uses of cocoa were also explored early on. For example, the Badianus Codex from 1552 mentions this.

Chocolate and sweets were served in Madrid in the 1600s. People in these places asked for the "drink that came from the Indies." Many visitors in the 1700s mentioned that chocolate was widely available. In 1680, cocoa was served with melted ice to nobles at public religious ceremonies. The writer Marcos Antonio Orellana wrote a short poem about its popularity:

- Oh, divine chocolate!

- that they grind you kneeling,

- they beat you with folded hands

- and drink you with eyes to heaven.

Noble women loved the drink so much that they wanted to drink it several times a day. They even asked to drink it in church! This annoyed the bishops. In 1861, they banned chocolate in churches during long sermons. Chocolatadas, which were social gatherings where chocolate was drunk after religious services, became popular.

The Golden Age of Chocolate

By the early 1600s, drinking chocolate became very popular in Spain. It was first accepted by the upper classes. Then, it slowly spread to other regions and social groups. Other foods from the Americas were not as accepted in Spanish society as cocoa. Most other new foods were only studied by scientists or used in new dishes on rare occasions. But chocolate became part of special palace events in the 1600s. It was offered to visitors as "entertainment." Ladies of the Court would offer their female guests chocolate with sweets like cakes and muffins. They also offered a vase of snow. The chocolate was served to visitors relaxing on cushions, surrounded by tapestries and warm braziers. Chocolatadas, the social custom of drinking chocolate together, first appeared in Spain.

During this century, two things helped cocoa spread. Spanish noblewomen married French royalty, and the Jesuits shared chocolate recipes in different countries, like Italy. Demand for cocoa grew a lot in the mid-1500s. The product flowed into Spanish seaports and then spread to the rest of Europe.

Chocolate's Acceptance by Spanish Rulers

New foods and drinks usually became popular first with the rich. Then, they slowly spread to poorer people who copied the rich. At first, the serious rulers of the House of Habsburg didn't like chocolate. Hernán Cortés mentioned chocolate to King Charles I in his letters from the Americas. After that, he convinced the emperor to try it for the first time in Toledo. By the early 1600s, drinking chocolate was fully accepted in the royal court. It was a regular part of royal morning gatherings. Soon after, chocolate was served in a similar way in all Spanish homes in big cities. The English traveler Ellis Veryard, who visited Spain in 1701, wrote about how highly chocolate was thought of in Spain. He described how chocolate was made: carefully grinding cocoa in portable stone mills and mixing it with cinnamon, vanilla, and a little annatto. In 1644, Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma published one of the first Spanish chocolate recipes. This recipe became standard in Spain and Europe by the late 1500s. Colmenero translated his own work into English, and it spread across Europe. Spanish doctors who believed in the theory of the four bodily humours (including Colmenero) thought chocolate had a "cold and dry" nature and caused sadness. One ingredient in Colmenero's recipe was mecaxochitl (a type of pepper). He said that if this wasn't available, a type of rose could be used.

How Chocolate Spread from Spain to Europe

The way chocolate was brought to Spanish ports shows that it was one of the most valuable goods from overseas in the 1600s. In 1691, there was an attempt to limit its distribution, but most merchants in Andalusia opposed it. Chocolate was brought to France by the Jesuits. It was also promoted by Spanish queens: Anne of Austria (daughter of Philip III of Spain and wife of Louis XIII of France) and Maria Theresa of Spain (daughter of Philip IV of Spain). Maria Theresa moved to France in 1660 to marry Louis XIV of France (the Sun King). As a result, chocolate became very popular in Paris in the 1600s. The famous writer Voltaire even mentioned this drink in his works in the 1700s.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del chocolate para niños

In Spanish: Historia del chocolate para niños