Porbeagle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Porbeagle |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Lamna

|

| Species: |

nasus

|

|

|

| Confirmed range Suspected range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Lamna philippii Perez Canto, 1886 |

|

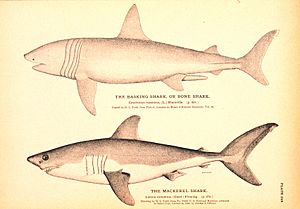

The porbeagle (Lamna nasus) is a type of mackerel shark. It lives in the cold and cool waters of the North Atlantic Ocean and the Southern Hemisphere. In the North Pacific, a similar shark called the salmon shark lives. Porbeagles usually grow to about 8 feet (2.5 meters) long and weigh around 300 pounds (135 kg). Sharks in the North Atlantic are often bigger than those in the Southern Hemisphere.

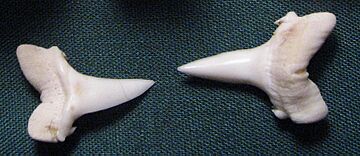

This shark is gray on top and white underneath. It has a strong, thick body that gets thinner towards its pointed snout and tail. The porbeagle has large pectoral fins and a big first dorsal fin. Its other fins are quite small. A special feature is its crescent-shaped tail. You can also spot a porbeagle by its unique teeth, which have three points, and a white spot at the back of its first dorsal fin. It also has two pairs of ridges (called keels) on its tail.

The porbeagle is a skilled hunter. It eats mostly bony fish and cephalopods like squid. It hunts throughout the water, even near the bottom. These sharks often live near food-rich areas on the outer continental shelf. They sometimes go close to shore or into the open ocean, diving as deep as 4,460 feet (1,360 meters). Porbeagles also travel long distances with the seasons, moving between shallow and deep waters.

This shark is very fast and active. It can keep its body warmer than the surrounding water, which helps it stay active in cold seas. Porbeagles can be alone or in groups. They have even been seen doing things that look like playing. Baby porbeagles grow inside their mother and feed on unfertilized eggs. Females usually have four pups each year.

There have been very few reports of porbeagles biting people, and none have been deadly. People who fish for sport like to catch porbeagles because they put up a good fight. The meat and fins of the porbeagle are very valuable. This has led to a lot of fishing for them. However, this shark cannot handle heavy fishing because it does not have many babies. Because of too much fishing, porbeagle numbers dropped sharply in the North Atlantic in the 1950s and 1960s. Today, the porbeagle is considered a vulnerable species worldwide. In some northern areas, it is even endangered or critically endangered.

Contents

What is a Porbeagle?

The name "porbeagle" is a bit of a mystery. Some people think it comes from "porpoise" (a sea animal) and "beagle" (a dog), because of the shark's shape and how it hunts. Another idea is that it comes from old Cornish words meaning "harbor" and "shepherd".

The first scientific description of the porbeagle was written by a French scientist named Pierre Joseph Bonnaterre in 1788. He named the shark Squalus nasus. The word nasus is Latin for "nose." Later, in 1816, another scientist placed the porbeagle into its own group called Lamna.

Shark Family Tree

Scientists have studied the porbeagle's body and mitochondrial DNA (a type of genetic material). These studies show that the porbeagle and the salmon shark are very closely related. They are like "sister species." The group of sharks called Lamna started to evolve about 45 to 65 million years ago. The porbeagle and salmon shark likely became separate species when the ice cap formed over the Arctic Ocean. This ice separated the sharks in the North Pacific from those in the North Atlantic.

Fossils of porbeagle sharks have been found from millions of years ago. Some teeth that look like porbeagle teeth have been found from as far back as 50 to 34 million years ago.

Where Porbeagles Live

The porbeagle lives in cool waters all over the world, but not in tropical (warm) areas. You can find them mostly between 30 and 70 degrees North latitude and 30 and 50 degrees South latitude. In the North Atlantic, they live from Canada and Greenland to Scandinavia and Russia. Their southern range goes from New Jersey to Morocco. They are also found in the Mediterranean Sea. In the Southern Hemisphere, they live in a band around the world, from Chile and Brazil to South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.

Porbeagles love to hang out on fishing banks, which are shallow areas of the ocean floor rich in food. But they can be found from very deep waters (over 4,400 feet or 1,360 meters) to very shallow waters (less than 3 feet or 1 meter) near the shore. They can be found in water temperatures from 34 to 73 degrees Fahrenheit (1 to 23 degrees Celsius). Most often, they are in water between 46 and 68 degrees Fahrenheit (8 and 20 degrees Celsius).

Sharks in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres seem to be completely separate groups. In the North Atlantic, there are two main groups: one in the east and one in the west. These groups rarely mix. Porbeagles also tend to separate by size and sex. For example, in some areas, there are more males than females, or more young sharks than old ones. Older, larger sharks might prefer colder, northern waters.

Porbeagles also make seasonal journeys. In the western North Atlantic, many sharks spend spring in deep waters off Nova Scotia. Then they travel north up to 600 miles (1,000 km) to spend late summer and fall in the shallow waters of the Newfoundland Grand Banks. Large, pregnant females travel even further south (over 1,200 miles or 2,000 km) to the Sargasso Sea to give birth. They stay deep during the day to stay in cooler waters. In the South Pacific, sharks move north into warmer waters in winter and spring, and then back south in summer.

What Porbeagles Look Like

The porbeagle has a very strong, torpedo-shaped body. Its long, pointed snout is supported by strong cartilage. Its eyes are big and black. The mouth is large and curved, with jaws that can push out. North Atlantic porbeagles have slightly different numbers of teeth rows than Southern Hemisphere sharks. Each tooth has a strong, pointed main cusp and two smaller points on the sides. It has five long gill slits in front of its pectoral fins.

The pectoral fins are long and thin. The first dorsal fin is large and tall, starting just behind the pectoral fins. The other fins (pelvic, second dorsal, and anal) are much smaller. The sides of its tail base have strong ridges called lateral keels. There's also a second, smaller pair of keels below the main ones. The tail fin is large and shaped like a crescent, with the bottom part almost as long as the top.

The porbeagle's skin is soft and feels like velvet. It is covered in tiny, flat scales. The top of the shark is medium to dark gray. Its belly is white. Southern Hemisphere adults often have dark coloring under their heads and dark spots on their bellies. A unique feature of this shark is the white or light gray tip on the back of its first dorsal fin.

Porbeagles can grow up to 12 feet (3.7 meters) long, but usually they are around 8 feet (2.5 meters). In the North Atlantic, females grow larger than males. Females can reach about 10 feet (3.0 meters), while males reach about 8 feet (2.5 meters). Southern Hemisphere sharks are smaller, with both sexes growing to about 6.5 to 7 feet (2.0 to 2.1 meters). Most porbeagles weigh around 300 pounds (135 kg). The heaviest recorded porbeagle weighed 507 pounds (230 kg).

Porbeagle Life and Habits

The porbeagle is a fast and energetic shark. It can be found alone or in groups. Its streamlined body, narrow tail base with keels, and crescent-shaped tail all help it swim very fast and efficiently. These features are similar to those found in fast fish like tuna. The porbeagle's large gill area helps it get a lot of oxygen to its body. It also has special "red muscle" that helps it swim for a long time without getting tired.

Porbeagles are one of the few fish that seem to "play." People have seen them rolling around and wrapping themselves in long kelp plants near the surface. They might be exploring, trying to scratch off parasites, or just having fun. They have also been seen chasing each other and playing with floating objects like driftwood or fishing floats.

Large sharks like Great white sharks and killer whales might hunt porbeagles, but this has not been seen often. Small porbeagles have been found with bite marks from other sharks, but it's not clear if they were being hunted. Porbeagles can have parasites like tapeworms and copepods. In the wild, not many porbeagles die each year naturally.

What Porbeagles Eat

The porbeagle is an active predator that mainly eats small to medium-sized bony fish. It chases down fish that swim in the open water, like mackerel and herring. It also hunts near the bottom for fish like cod and hake. Cephalopods, especially squid, are also a big part of its diet. Sometimes, it might eat smaller sharks, but this is rare. Scientists have found small molluscs, crustaceans, and other small sea creatures in their stomachs. These were likely eaten by accident. They have also found things like small stones and feathers.

In the western North Atlantic, porbeagles eat mostly open-water fish and squid in the spring. In the fall, they eat more bottom-dwelling fish. This changes with their seasonal travels and what food is available. Porbeagles seem to be opportunistic hunters, meaning they eat whatever is easiest to find. They often gather in areas where tides create good feeding grounds. Hunting porbeagles regularly dive from the surface to the bottom and back up again. This movement might help them find food by smell. Even young porbeagles have been seen eating tiny krill and polychaete worms.

Porbeagle Life Cycle

The porbeagle's reproduction cycle is unusual because it is similar in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, even though the seasons are opposite. This might be because their warm bodies help them not be affected by temperature or day length. Mating usually happens between September and November. Males bite the female's fins and body during courtship.

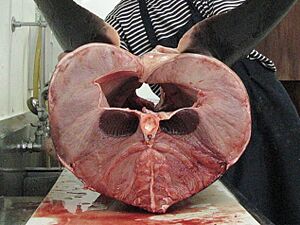

Female porbeagles have one working ovary and two working uteri. They likely have babies every year. A female usually has four pups, with two babies in each uterus. Sometimes, there can be as few as one or as many as five pups. Pregnancy lasts for 8 to 9 months.

Like other sharks in its family, the porbeagle gives birth to live young. The babies grow inside the mother and feed on unfertilized eggs. During the first half of pregnancy, the mother produces many tiny eggs. A new embryo is nourished by a yolk sac. When the embryo is about 4 to 5 inches (10 to 12 cm) long, it grows two large, curved "fangs" in its lower jaw. These fangs help it tear open the egg capsules to eat the yolk. The embryo's stomach gets very big to hold all the yolk.

When the embryo is about 13 to 15 inches (34 to 38 cm) long, it starts to get its color and loses its fangs. At this point, the mother stops producing eggs. The embryo then relies on the yolk stored in its stomach. Its stomach shrinks, and its liver grows. By about 23 inches (58 cm) long, the embryo looks like a newborn shark.

Newborn porbeagles are about 23 to 26 inches (58 to 67 cm) long and weigh less than 11 pounds (5 kg). Their liver makes up a big part of their weight, and some yolk is still in their stomach to feed them until they learn to hunt. Babies grow about 3 inches (7-8 cm) per month. Sometimes, one baby in a uterus is much smaller than the others.

Birth happens from April to September. For North Atlantic sharks, it peaks in April and May. For Southern Hemisphere sharks, it peaks in June and July. In the western North Atlantic, babies are born far offshore in the Sargasso Sea, at depths around 1,640 feet (500 meters).

Both male and female porbeagles grow at similar rates until they become adults. Females mature later and at a larger size. In the North Atlantic, males become adults at 6 to 11 years old and about 5 to 6 feet (1.6 to 1.8 meters) long. Females become adults at 12 to 18 years old and about 6.5 to 7 feet (2.0 to 2.2 meters) long. In the Southwest Pacific, sharks mature a bit smaller and earlier. The oldest porbeagle found was 26 years old and about 8 feet (2.5 meters) long. These sharks can live for 30 to 40 years in the Atlantic, and possibly up to 65 years in the South Pacific.

Keeping Warm

Like other sharks in its family, the porbeagle is warm-blooded. This means it can keep its body temperature warmer than the surrounding water. It does this using special networks of blood vessels called retia mirabilia (which means "wonderful nets" in Latin). These networks act like efficient heat exchangers, keeping the heat from its muscles inside its body.

The porbeagle has several of these "wonderful nets" that warm its brain, eyes, swimming muscles, and other organs. The porbeagle can raise its body temperature by 14–18°F (8–10°C) compared to the water. Only the salmon shark can get warmer. Being warm-bodied helps the porbeagle swim faster, hunt in deep, cold water for longer, and travel to colder areas to find food that other sharks cannot reach. Warming its brain and eyes by 5–11°F (3–6°C) helps it see better and react faster, especially when diving into different water temperatures.

Porbeagles and People

The porbeagle has very rarely, if ever, bitten swimmers or boats. As of 2009, there were only three reported incidents involving this species, one was provoked and none were deadly. Two incidents involved boats. One old story tells of a fisherman who made a porbeagle jump out of the water and tear his clothes. Another story about a swimmer bitten by a "mackerel shark" might have been a different species, like a shortfin mako or great white shark. Recently, in the North Sea, adult porbeagles have been filmed swimming close to divers working on oil platforms. They sometimes even brush against them without causing harm. These actions don't seem to be about hunting. They might be out of curiosity or defense.

On May 14, 2018, a porbeagle shark was reported to have bitten a fisherman off the coast of Cornwall, United Kingdom. This happened as the shark was being put back into the sea.

Some commercial fishers used to see porbeagles as a problem because they would damage fishing gear and take fish off lines. However, this shark is highly valued by people who fish for sport in Ireland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It fights hard when caught on a line, but it usually doesn't jump out of the water like the mako shark. New anglers sometimes confuse the porbeagle with the mako.

Commercial Fishing for Porbeagles

Porbeagles have been heavily fished for a long time because their meat and fins are very valuable. The meat is sold fresh, frozen, or dried and salted. It is one of the most valuable shark meats. Most of the demand comes from Europe, but the United States and Japan also buy it. The fins are sent to East Asia to be used in shark fin soup. Other parts of the shark can be used for leather, liver oil, and fishmeal.

International trade in porbeagles is big, but it's hard to track because shark products are often not labeled by specific species. Porbeagles are most easily caught with longlines, but they can also be caught in gillnets, driftnets, and trawls. Because they are so valuable, they are usually kept when caught by accident.

Heavy fishing for porbeagles started in the 1930s, mainly by Norway and Denmark in the Northeast Atlantic. Norwegian catches grew very fast, peaking around 6,000 tons in 1947. Soon after, the shark population crashed. Norwegian catches dropped steadily over the next decades. Other countries like France and Spain also started fishing for porbeagles in the 1970s, and their catches also declined. Since 2011, it has been illegal to fish for porbeagles in European Union waters. Norway also put similar rules in place in 2012.

As porbeagles became rare in the Northeast Atlantic, Norwegian fishing boats moved to the waters off New England and Newfoundland in the 1960s. Catches quickly rose again, peaking at over 9,000 tons in 1965. But again, the population crashed in just six years. By 1970, catches had fallen sharply. With the population so low, most fishers moved on. Porbeagle numbers slowly recovered over the next 25 years, reaching about 30% of their original levels. In 1995, Canada became the main country fishing for porbeagles in this area. Between 1994 and 1998, Canadian boats caught 1,000–2,000 tons each year. This caused the population to drop to only 11–17% of its original size by 2000. Strict rules and much lower fishing limits were put in place in 2000. These have started to help the population recover, but it will take decades because the shark does not reproduce quickly.

In the Southern Hemisphere, commercial fishing for porbeagles is not well recorded. Many are caught by accident by boats fishing for other valuable species like southern bluefin tuna and swordfish. New Zealand has reported catching 150–300 tons each year from 1998 to 2003, mostly young sharks.

Protecting Porbeagles

The quick drop in porbeagle numbers in the North Atlantic is a classic example of how most shark fisheries work: a quick "boom" in catches followed by a "bust" or crash. This shark is very sensitive to overfishing because it has few babies, takes a long time to mature, and sharks of all ages are caught. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed the porbeagle as vulnerable worldwide. It is listed as endangered in the western North Atlantic and critically endangered in the eastern North Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea.

The porbeagle is listed on international agreements like the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the Conservation of Migratory Species. Many countries and groups, including Canada, the United States, and the European Union, have banned shark finning. In March 2013, the porbeagle was added to Appendix II of Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). This allows for more rules on the international trade of this shark.

In March 2015, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) in the US began looking into whether the shark should be listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

Southern Hemisphere Protection

The only rule for porbeagle catches in the Southern Hemisphere is New Zealand's limit of 249 tons per year, set in 2004. In June 2018, New Zealand's Department of Conservation said the porbeagle was "Not Threatened" in New Zealand, but "Threatened Overseas."

Eastern North Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea Protection

In the eastern North Atlantic, fishing for porbeagles has been illegal in European Union waters since 2011. Before this ban, Norway and the Faroe Islands had annual limits, but these were often higher than the actual catches, so they didn't help much. Norway has protected the porbeagle in its national waters since 2012. Any porbeagle caught by accident in EU or Norwegian waters must be released.

In the Mediterranean Sea, the porbeagle is almost gone. Its population has dropped by over 99.99% since the mid-1900s. It is now mostly found around the Italian Peninsula. Only a few dozen have been seen in recent decades. Despite being listed on international agreements, new management plans have not yet been put in place. The European Union has banned EU vessels from fishing for, keeping, or landing porbeagle sharks in all waters since January 2011.

Western North Atlantic Protection

The porbeagle population in the western North Atlantic has a better chance of recovery. Fishing in Canadian waters was first managed by a plan in 1995, which set a limit of 1,500 tons per year. In 2000–2001, Canada set a lower limit of 250 tons per year to help the population grow. Areas where porbeagles mate off Newfoundland were also closed to shark fishing. In 2004, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada listed the porbeagle as endangered because its numbers were very low. Canada decided not to list the species under its Species At Risk Act, but it lowered the fishing limit even more to 185 tons. In US waters, the annual limit for porbeagles is 92 tons. In 2006, the NMFS listed this species as a "species of concern," meaning it needs conservation, but there wasn't enough data to list it under the US Endangered Species Act.

|