National Museum of Ireland – Archaeology facts for kids

| Ard-Mhúsaem na hÉireann – Seandálaíocht | |

Entrance to the museum

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Established | 29 August 1890 |

|---|---|

| Location | Kildare Street, Dublin, Ireland |

| Type | National museum |

| Visitors | 505,420 (2019) |

| Public transit access | St Stephen's Green Dublin Pearse Dublin Bus routes: 39, 39a, 46a, 145 |

| National Museum of Ireland network | |

|

|

The National Museum of Ireland – Archaeology (also known as the "NMI") is a super cool museum in Dublin, Ireland. It's a special part of the National Museum of Ireland. This museum is all about ancient Irish objects and other old treasures. You can see things from the Stone Age all the way up to the Late Middle Ages. It's like a time machine for history!

The museum was officially started in 1877. Before that, its amazing collections were split between two other places. The famous father-and-son architects, Thomas Newenham Deane and Thomas Manly Deane, designed the building. The round entrance of the National Museum looks just like the National Library of Ireland building across the street.

The NMI has tons of artifacts from prehistoric Ireland. These include ancient bog bodies, and objects from the Iron Age and Bronze Age. You can see axe heads, swords, and shields made of bronze, silver, and gold. Some of these items are super old, dating back to about 7000 BC! The museum also has the world's biggest collection of Irish medieval art from after the Roman era. Plus, there are cool Viking artifacts like swords and coins, and even ancient objects from Ancient Egypt, Cyprus, and the Roman world.

Contents

Discovering Ireland's Past

The idea for this museum came about in 1877. It brought together collections from two important groups: the Royal Irish Academy (RIA) and the Royal Dublin Society (RDS). This new plan helped the RIA get government money to keep finding and buying old items. It also made it easier to work with big museums like the British Museum.

Many items in the museum's collection came from places like Trinity College Dublin. Some famous pieces include the Cross of Cong and the Domnach Airgid. In the mid-1800s, the museum also got collections from people like George Petrie. He left about 1500 artifacts, including many prehistoric items and old church objects.

Many of these treasures were found in the 1800s by farmers. As more land was farmed, old objects that had been hidden for centuries started to appear. People like George Petrie worked hard to stop these metal items from being melted down. Even today, new discoveries are still being made! For example, the 8th-century Tully Lough Cross was found in 1986. The Clonycavan bog bodies were discovered in 2003.

In 1908, the museum changed its name to the National Museum of Science and Art. After Ireland became independent in 1921, it was renamed the National Museum of Ireland.

The Museum Building: A Grand Design

The museum building you see today on Kildare Street opened on August 29, 1890. It was designed by Thomas Newenham Deane and his son, Thomas Manly Deane. They used a grand Victorian style called Palladian. The tall columns at the entrance and the round, domed rotunda are made from beautiful Irish marble. They were inspired by ancient Roman buildings like the Pantheon. The outside walls are mostly made of Leinster granite, and the columns are from sandstone found in County Donegal.

Inside, the mosaic floors show scenes from old myths. These floors were created in the 1800s but were covered up for many years. They were cleaned and brought back to life in 2011! The wooden doors were carved by skilled artists. The fireplaces have colorful tiles made by a UK company. The balcony in the main hall is held up by thin iron columns decorated with cute little cherubs.

Amazing Collections to Explore

The NMI has many permanent exhibits, mostly showing Irish historical objects. There are also smaller exhibits about ancient Mediterranean cultures. You can explore galleries on Ancient Egypt and see "Ceramics and Glass from Ancient Cyprus."

Prehistoric Ireland: From Stone to Gold

Early Tools and Treasures

The museum's prehistoric Ireland exhibit shows artifacts from the very first people who lived in Ireland. This was right after the last Ice Age, up to the time of the Celtic Iron Age. You'll see many stone tools made by the first hunter-gatherers around 7000 BC. There are also tools, pottery, and burial items from early farmers. Some special items include four rare Jadeite axeheads brought from the Alps in ancient Italy. There's also a unique ceremonial macehead found at the famous tomb of Knowth.

The exhibit then shows how metalworking came to Ireland around 2500 BC. You can see early copper tools. The museum has a huge collection of later Bronze Age items. These include axes, daggers, swords, shields, and even ancient musical instruments like bronze horns. There are also some very early Iron weapons. You can also see wooden objects like a large dugout logboat, wooden wheels, and old fishing gear.

-

River Bann Axehead, Neolithic period

-

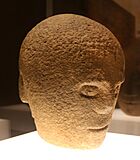

The Corleck Head, a 1st or 2nd century AD three-faced stone head found in Drumeague, County Cavan, Ireland around 1855.

Sparkling Gold from the Bronze Age

The NMI has one of the "largest and most important" collections of Bronze Age gold in Western Europe. These gold items date from about 2200 to 1800 BC. The gold was found in river gravel and hammered into thin sheets. These sheets were used to make beautiful objects like crescent-shaped collars (Gold lunula), bracelets, and dress-fasteners. Most of these gold items were probably jewelry. However, some objects have a mysterious, possibly ritual, purpose.

Later in the Middle Bronze Age, new ways of working with gold were developed. From around 1200 BC, many different kinds of torcs were made by twisting gold bars. Items from the Late Bronze Age (around 900 BC) include solid gold bracelets, large gold collars, and necklaces of hollow golden balls.

-

Gold lunula, Coggalbeg hoard, 2200-1800 BC

-

Gold dress fastener from Killymoom Demesne in County Tyrone (800-700 BC)

Mysterious Bog Bodies from the Iron Age

The museum has several incredibly well-preserved Irish bog bodies from the Iron Age. Some experts believe these people were part of ancient ritual sacrifices. One idea is that they were tribal kings who were sacrificed if they failed their people. They might have been drowned in special pools of water. Some bodies even show signs of a "threefold death," meaning they were strangled, wounded, and drowned.

The bog bodies in the collection include Cashel Man (around 2000 BC), who might be the oldest fleshed bog body found in Europe. There's also Gallagh Man (470-120 BC), Clonycavan Man (392 to 201 BC), Old Croghan Man (362 to 175 BC), and Baronstown West Man (242 to 388 AD).

These bodies are all males, aged 25 to 40, who died in violent ways. The rope found around Gallagh Man's neck might have been used to strangle him. While he could have been a criminal, the willow rope suggests a ritual sacrifice, as this often appears in old Irish stories.

You can see these bodies alongside other items from the Celtic Iron Age. These include metal weapons, horse gear, and wooden and leather pieces. One interesting item is the Ralaghan Idol, a carved wooden figure found in County Cavan.

-

Clonycavan Man, 392 to 201 BC, found in County Meath, 2003

Early Medieval Treasures: Art and Faith

The museum's treasury room shows off early medieval Irish metalwork. These items date from the late Iron Age to the late 12th century. You'll see important pieces from both the La Tène and Insular periods. Early works show influences from Anglo-Saxon art and Germanic Europe. Later pieces, after the late 8th century, show the influence of Viking art.

Chalices, Crosses, and Relics

The items in the Treasury room are arranged by time. You can start with pieces like the late 7th-century Rinnegan Crucifixion Plaque. This is one of the earliest pictures of the crucifixion in Irish art.

Bell shrines are common artifacts from this time. The most famous ones in the museum are St. Columba's bell and the bell and shrine of St. Patrick.

The "Golden Age" of Irish art began in the 8th century with church metalwork. This includes beautiful reliquaries (containers for holy relics) and items used in church services. Examples are the 8th-century Moylough Belt-Shrine and the 8th or 9th-century Ardagh and Derrynaflan chalices. The Viking invasions starting in the 10th century changed Irish metalwork. New materials like silver and amber became available, and Scandinavian styles were adopted.

-

Chalice from the Ardagh Hoard, 8th- or 9th-century

-

Derrynaflan Chalice, 8th- or 9th-century. Part of the Derrynaflan Hoard found in 1980 near Killenaule, County Tipperary.

-

Shrine of Saint Lachtin's Arm, around 1118–1121. A reliquary shaped like an arm.

Many of these objects were lost long ago and only found again in the 1800s and 1900s. The museum has been key in figuring out their age, fixing them, and keeping them safe. Recent big finds include the Tully Lough Cross (1986) and the Faddan More Psalter (around 800 AD), found in a bog in 2006.

Beautiful Brooches

The museum has many fancy Celtic brooches. These were used to fasten clothes for important people in Ireland and Scotland. Men usually wore them on one shoulder, and women on their chest. Brooches are very important examples of high-quality metalwork from the Early Medieval period. Later, middle-class people also wore them. The most detailed brooches showed off a person's high status. Even clergy wore them to fasten their special robes.

The Vikings started raiding Ireland in 795. This was a tough time for monasteries. However, the Irish were better than the English at stopping large Viking settlements. During this time, there was a lot more silver available, probably from Viking raids and trade. Most brooches from this period are made entirely of silver. They are often large but simpler than the earlier, more decorated ones.

The early 8th-century Tara Brooch is thought to be the most complex and beautiful medieval brooch. It has been shown all over the world. It even helped inspire the Celtic Revival movement in the mid-1800s. The 9th-century Roscrea Brooch is an example of a brooch that shows a mix of styles. Later Irish brooches show Viking influences in their style and techniques.

-

9th century silver brooch, Rathlin Island, County Antrim

-

The Kilmainham Brooch, late 8th- or early 9th-century. Its design was influenced by both Pictish and Viking metalwork.

-

Penanular Celtic brooch, County Meath, 9th century

House-Shaped Shrines

House-shaped shrines come from Europe, Ireland, and Scotland. Most are from the 8th or 9th centuries. Like many Irish shrines, they were often changed and decorated more over the years. They usually have a wooden core covered with silver and copper alloy plates. These shrines were made to hold relics of saints or martyrs from early Christian times. Some even held parts of a saint's body when they were found! Others, like the damaged Breac Maodhóg, held old manuscripts.

The Breac Maodhóg was probably used as a battle flag. A priest would carry it into battle to protect soldiers and help them win. Old texts say that kings would have the "famous wonder-working Breac" carried around them three times during a fight.

-

Drawing of a shrine found in the River Shannon, around 9th century

Book Shrines (Cumdachs)

Cumdachs are fancy, decorated metal boxes or cases. They were used to hold Early Medieval Irish manuscripts or relics. These cases are usually much newer than the books they hold, sometimes by hundreds of years. Most surviving books inside are from the peak of Irish monasteries before 800 AD. The cases themselves are usually from after 1000 AD.

The typical design for a cumdach is a cross on the front. They often have large rock crystals or other semi-precious stones. The spaces between the arms of the cross have more decorations. Many were carried on a metal chain or leather cord, often worn around the neck or from a belt. This was thought to offer spiritual or even healing benefits. They were also used to help the sick or to witness important agreements. Many families who had connections with monasteries kept these shrines for generations.

Most of these book shrines are mentioned in old Irish records. However, they weren't properly described until the early 1800s. That's when people like Petrie started looking for them in family collections. Most are damaged from centuries of use, fires, or because their precious stones were removed and sold. Most of the surviving cumdachs are now in the NMI.

-

The shrine of the Stowe Missal, showing openwork patterns

-

Shrine of Miosach, 11th century. May have once contained a manuscript with psalms or extracts from a Gospel

-

The Shrine of the Cathach of St. Columba, 11th century

-

Detail from the 11th century Soiscél Molaisse showing St. Matthew

Shepherd's Croziers

The NMI has most of the surviving Insular croziers. These are special staffs carried by bishops or abbots in Ireland and Scotland between about 800 and 1200 AD. They look different from European croziers because of their curved tops and a hollow box-like part at the end. They were symbols of power for church leaders, showing them as shepherds guiding their followers.

Even though they stopped being made around 1200, they were still used and often updated until the late medieval period. After monasteries were closed down, these croziers were in danger from Viking and Norman invaders. Since they were large, they were hard to hide. That's why many surviving ones were broken in half, making them easier to hide in small places. Most of the croziers we have today were kept by local families for centuries until they were found by historians in the early 1800s.

The croziers are often decorated with interlace designs, geometric patterns, and animal-like figures. The animal designs on earlier ones, like the 9th-century Prosperous Crozier, look very natural. Later ones, like the Lismore Crozier from around 1100, show influences from Viking art styles. The late 11th-century Clonmacnoise Crozier is considered the most beautifully made and complete example.

Late Medieval Life in Ireland

During the 12th century, Viking port cities like Dublin, Waterford, and Cork started trading a lot with Britain and Europe. This brought new styles to Ireland and slowly ended the unique Irish art period. The older style mostly finished after church reforms and the Norman invasion in 1169–1170. After that, Irish art became more like the wider European styles.

The English settling in Ireland meant the island had two different cultures in the late Middle Ages. Each had its own language, laws, and ways of life. You can see this in the objects from that time in the museum. The museum considers this late period to be from about 1150 to 1550. However, there's some overlap with the earlier "golden age" of Irish art.

The museum shows its later collection in three groups: "bellatores" (those who fight), "oratores" (those who pray), and "laboratores" (those who work). This helps visitors understand the different parts of medieval society.

-

Copper-alloy crucifix figurine, County Wicklow, 12th century

-

Remains of a bascinet made of iron, 14th–15th century. Found in Clashnamuck, County Laois.

-

Silver cross pendant with glass and garnets, around 1500. Found near Callan, County Kilkenny

-

Pendant with crucifix, gilded silver, around 1500, County Waterford

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |