Puebloan peoples facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 75,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Southwestern United States | |

| Particularly: New Mexico and Arizona | |

| Languages | |

| English, Spanish, Hopi, Tanoan languages, Keresan, Keresan Pueblo Sign Language, Zuni | |

| Religion | |

| Kachina religion, Roman Catholicism, minority Protestantism |

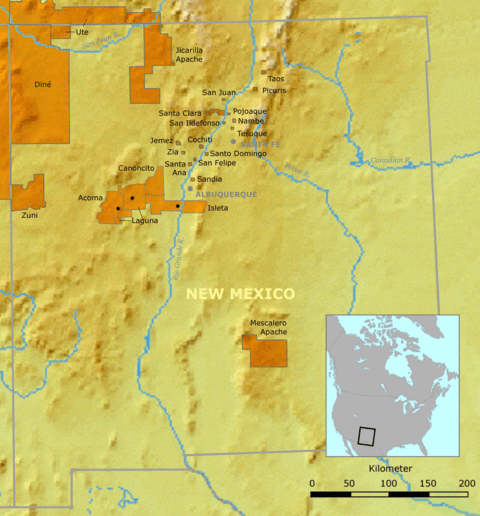

The Puebloans, also called Pueblo peoples, are Native Americans who live in the Southwestern United States. They share similar ways of farming, making things, and religious practices. Some well-known Pueblo communities today include Taos, San Ildefonso, Acoma, Zuni, and Hopi.

Pueblo people speak languages from four different language families. Each Pueblo also has its own cultural differences, like family systems and farming methods. However, all Pueblo groups grow different types of corn (maize).

Pueblo peoples have lived in the American Southwest for thousands of years. They are descendants of the ancestral Puebloans. The word Anasazi was sometimes used for ancestral Pueblo people. But it is now mostly avoided. Anasazi is a Navajo word that means Ancient Ones or Ancient Enemy. Because of this, Pueblo peoples do not like the term.

Pueblo is a Spanish word for "village". When Spanish explorers arrived in the 1500s, they found complex, multi-story villages. These villages were built from adobe, stone, and other local materials. New Mexico has the most federally recognized Pueblo communities. Some Pueblo communities also live in Arizona and Texas. They often live along the Rio Grande and Colorado rivers.

Pueblo nations have kept much of their traditional cultures. These cultures focus on farming, strong family groups, and respecting old traditions. Puebloans have been very good at keeping their culture and religious beliefs alive. This includes mixing some Pueblo beliefs with Christianity. Today, about 75,000 Pueblo people live mainly in New Mexico and Arizona. Some also live in Texas and other places.

Contents

How are Pueblo Peoples Grouped?

Even though Pueblo peoples share many cultural and religious practices, experts divide them into smaller groups. These groups are based on their languages and unique cultural differences.

Different Languages of the Pueblos

The clearest way to divide Puebloans is by the languages they speak. Pueblo peoples speak languages from four different language families. This means their languages have completely different words and grammar. Because of this, people speaking one Pueblo language cannot easily understand another. English is now often used as a common language in the region.

- Keresan: This family includes Western and Eastern Keres. Some people think it is a language isolate. It is spoken at the pueblos of Acoma, Laguna, Santa Ana, Zia, Cochiti, Kewa, and San Felipe.

- Kiowa-Tanoan: This family includes the Tanoan branch. It has three separate sub-branches:

- Towa: Only spoken at Jemez Pueblo.

- Tewa: The most common Tanoan language with several dialects. It is spoken at Ohkay Owingeh, San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Tesuque, Nambé, and Pojoaque Pueblos.

- Tiwa: The only Tanoan sub-branch with separate languages:

- Northern Tiwa: Has two dialects, spoken at Taos and Picuris.

- Southern Tiwa: Also has two dialects, spoken at Sandia and Isleta Pueblos.

- Uto-Aztecan: This family includes Hopi. It is spoken only at Hopi Pueblo.

- Zuni: This family includes Zuni. It is a language isolate, meaning it is not related to other languages. It is spoken only at Zuni Pueblo.

Pueblo Cultural Traditions

Experts have studied Pueblo peoples a lot. They have found different ways to group them based on their culture. In 1950, Fred Eggan compared Eastern and Western Pueblos. He looked at their farming methods. The Western or Desert Pueblos (Zuni and Hopi) used dry farming. The Eastern or River Pueblos used irrigation to water their crops. Both groups mainly grew corn, squash, and beans.

In 1954, Paul Kirchhoff also divided Pueblo peoples into two cultural groups. The Hopi, Zuni, Keres, and Jemez have matrilineal family systems. This means children belong to their mother's family group. They must marry someone from a different group. They use many kivas for sacred ceremonies. Their creation story says humans came from underground. They value four or six main directions in their beliefs. Four and seven are important numbers in their rituals.

In contrast, the Tanoan-speaking Puebloans (except Jemez) have a patrilineal family system. Children belong to their father's family group. They usually marry within their own group. They have two kivas or two groups of kivas. Their beliefs are based on dualism, meaning two opposing forces. Their creation story says people came from underwater. They use five directions, starting in the west. Their important ritual numbers are based on multiples of three.

History of the Pueblo Peoples

Early Cultures of the Southwest

Pueblo societies include parts of three main cultures that lived in the Southwest before Europeans arrived. These were the Mogollon culture, the Hohokam culture, and the Ancestral Pueblo culture. These groups lived in areas like the Gila Wilderness, Chaco Canyon, and Mesa Verde.

Archaeological findings show that Mogollon culture people first gathered food. Later, they started farming. By 1000 CE, farming became their main way to get food. They used water control systems. Early Mogollon villages had small pithouses, which were houses dug into the ground. Over time, villages grew. By the 11th century, houses were built above ground with rock and earth walls. Cliff-dwellings became common in the 13th and 14th centuries.

The Hohokam culture relied on irrigation canals to water their crops. They started using these canals as early as the 9th century CE. Their irrigation skills helped them become the largest population in the Southwest by 1300. Archaeologists found evidence that ancestors of the Hohokam lived in southern Arizona as early as 2000 BCE. This group grew corn, lived in villages year-round, and built advanced irrigation canals. The Hohokam area was a central trade spot for different cultures.

The Ancestral Puebloan culture is famous for its stone and earth homes. They built these homes along cliff walls, especially from about 900 to 1350 CE. Many of these well-preserved homes are now in national parks. These villages were often hard to reach, sometimes only by rope or climbing. The first Ancestral Puebloan homes were pit-houses. Later, they built apartment-like complexes from stone and adobe. These ancient towns were often multi-story buildings around open plazas. Hundreds to thousands of people lived in them. These complexes were centers for cultural events and supported a large surrounding region.

How Pueblo Architecture Developed

Around 700 to 900 CE, Puebloans started building connected rectangular rooms. These were like apartment buildings made of adobe. By 1050, they built planned villages with large terraced buildings. These villages were often built in places that were easy to defend. They were on rock ledges, flat hilltops, or steep-sided mesas. These locations protected Puebloans from raiding groups like the Comanche and Navajo.

The largest of these villages was Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. It had about 700 rooms and five stories. It may have housed up to 1000 people. Pueblo buildings are complex apartments with many rooms. The most advanced villages were large pueblos built on top of mesas.

European Arrival and the Pueblo Revolt

Before 1598, Spanish visits to Pueblo areas were brief. A group of Spanish settlers led by Juan de Oñate arrived in the late 1500s. Their goal was to convert Native peoples to Catholicism. At first, contact was peaceful. But Spain tried harder to replace Pueblo religion with Catholicism. Puebloans resisted greatly. Their government was led by a cacique, a spiritual and community leader. Over time, Spanish methods became harsher. This led to several revolts by the Puebloans.

The Pueblo Revolt began in 1680. It was the first time a Native American group successfully forced colonists out of North America for many years. It followed the Tiguex War (1540–41), where Tiwas fought against the Coronado Expedition. That war temporarily stopped Spanish advances in New Mexico. The 1680 revolt happened because Northern Pueblos were very unhappy with Spanish abuses. This led to a large, organized uprising.

Problems leading to the Pueblo Revolt started at least ten years before it began. In the 1670s, a severe drought hit the region. This caused famine for the Pueblo people. It also led to more raids by the Apache. Neither Spanish nor Pueblo soldiers could stop these Apache attacks.

Tensions among the Pueblos peaked in 1675. Governor Juan Francisco Treviño ordered the arrest of 47 Pueblo medicine men. He accused them of practicing sorcery. Four of them were sentenced to death by hanging. The others were publicly whipped and jailed. When Pueblo leaders heard about this, they marched to Santa Fe, where the prisoners were held. Many Spanish soldiers were away fighting the Apache. So, Governor Treviño had to release the prisoners.

One of the released men was Popé, a Tewa man from Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo. After being freed, Popé went to Taos Pueblo, far from Santa Fe. For the next five years, he gathered support for a revolt among the 46 Pueblo villages. He got help from the Northern Tiwa, Tewa, Towa, Tano, and Keres-speaking Pueblos. The Pecos Pueblo, Zuni, and Hopi also joined.

At that time, about 2,400 Spanish colonists lived in the region. This included mixed-blood people and Native servants. On August 10, 1680, Popé and Pueblo leaders sent a knotted rope by runner to each Pueblo. The number of knots showed how many days to wait before starting the uprising. Finally, on August 21, 2,500 Pueblo warriors took control of Santa Fe. They killed many colonists. The remaining Spanish were forced to leave.

On September 22, 2005, a statue of Po'pay (Popé) was put in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, D.C. This statue was the second from New Mexico for the National Statuary Hall Collection. It was the 100th and last statue added. It was made by Cliff Fragua, a Puebloan from Jemez Pueblo, New Mexico. It is the only statue in the collection made by a Native American.

Pueblo Culture and Traditions

In 1844, Josiah Gregg wrote about the Pueblo people. He said they lived in comfortable houses and farmed the land. He noted they were the best farmers in the area. They grew most of the fruits and vegetables for markets. They also raised cattle and horses. He described them as sober, hardworking, moral, and honest people.

Pueblo Crafts and Clothing

The Puebloans traditionally weave cloth. They use textiles, natural fibers, and animal hide to make clothing. Weaving clothes takes a lot of effort and time. So, everyday clothes for working around the villages were simpler. Men often wore breechcloths.

Farming and Food

Corn is the most important food for Pueblo peoples. Small, wild corn cobs have been found at sites in New Mexico and Arizona. This shows corn was grown there around 2100 BCE.

Corn came to the Southwest from Mesoamerica (present-day Mexico). People in the region quickly started growing it. One idea is that farmers speaking a Uto-Aztecan language brought corn north. Another, more accepted idea, is that corn spread from group to group between 4300 BCE and 2100 BCE. Corn was first grown in the Southwest when there was a lot of rain.

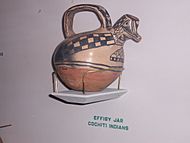

Pueblo Pottery

Different Pueblo communities have their own ways of making and decorating pottery. Archaeologists believe Puebloans have been using pottery since the early centuries CE.

-

San Ildefonso Pueblo Black-on-Black Pottery Bowl by Maria Martinez

-

Zuni owl figure, University of British Columbia

-

Bird effigy, pottery, Cochiti Pueblo. Field Museum

Pueblo Religion and Beliefs

In Southwest Native communities, important spirits are seen as beings who bring blessings. They receive love from people. Many religious stories explore how people relate to nature, including plants and animals. Spider Grandmother and kachina spirits are important in some myths.

In the 1500s, Puebloan peoples believed in Katsina spirits. Katsinas are supernatural beings who represent Pueblo ancestors. They live half the year in the underworld with the gods. The other half, they spend with their descendants on Earth. Katsinas can become clouds and bring rain for crops. They can also heal or cause illness.

Pueblo prayers included objects as well as words. A common prayer material was ground-up white cornmeal. A man might bless his son or land by sprinkling cornmeal while praying. After the Spanish returned in 1692, they were stopped from entering one town. A few men prayed and threw a pinch of a sacred substance.

Pueblo peoples used special 'prayer sticks'. These were colorful and decorated with beads, fur, and feathers. These sticks were like those used by other Native American nations. By the 13th century, Puebloans used turkey feather blankets for warmth.

Most Pueblos have annual sacred ceremonies. Some of these are now open to the public. Religious ceremonies often include traditional dances held outdoors in large common areas. These dances are accompanied by singing and drumming. Unlike kiva ceremonies, traditional dances may be open to non-Puebloans. Traditional dances are a form of prayer. Strict rules apply to those who attend. For example, no clapping or walking across the dance area.

Traditionally, all outside visitors to a public dance would be offered a meal in a Pueblo home. Because many tourists now attend these dances, such meals are only by personal invitation. Private sacred ceremonies happen inside the kivas. Only tribal members can participate, following specific rules for each Pueblo's religion.

One main goal of Spanish colonists in the 1600s was to convert Native peoples to Christianity. Franciscan priests built churches and missions across Pueblo lands. Some Pueblo feast days came from this process. Feast days are held on the day of a Roman Catholic patron saint. Spanish missionaries chose these days to match existing Pueblo ceremonies. Alfonso Ortiz, an Ohkay Owingeh anthropologist, said that the Spanish government demanded labor and tried to stop native religion. He noted that after 1692, the Spanish were gentler. But the Pueblos learned to keep their ceremonies secret while seeming to adopt Catholicism.

Public celebrations may also include a Roman Catholic Mass and processions on the Pueblo's feast day. Some Pueblos also have sacred ceremonies around Christmas and other Christian holidays.

Federally Recognized Pueblo Tribes

New Mexico Pueblos

- Acoma Pueblo – Keres speakers. Known for its location on top of a mesa. It was built in the 12th century. It is one of the oldest places in the United States where people have continuously lived.

- Cochiti Pueblo – Keres speakers. Famous for its ceramic storyteller figurines and drums.

- Isleta Pueblo – Tiwa speakers. Built in the 14th century. Located near Albuquerque.

- Jemez Pueblo – Towa speakers. Known for its runners and running ceremonies.

- Kewa Pueblo (formerly Santo Domingo) – Keres speakers. Known for turquoise jewelry and the Corn Dance.

- Laguna Pueblo – Keres speakers. Known for its well-preserved 17th-century mission church.

- Nambé Pueblo – Tewa language speakers. Built in the 14th century. It was an important trading center for the Northern Pueblos.

- Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo (formerly San Juan) – Tewa speakers. This is the main office for the Eight Northern Indian Pueblos Council. It is the home of Popé, a leader of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt.

- Picuris Pueblo – Tiwa speakers. Known for its micaceous pottery.

- Pojoaque Pueblo – Tewa speakers. Re-established in the 1930s.

- Sandia Pueblo – Tiwa speakers. Built in the 14th century. Located near Albuquerque.

- San Felipe Pueblo – Keres speakers.

- San Ildefonso Pueblo – Tewa speakers. Famous for its valuable black-on-black pottery. Located between Pojoaque and Los Alamos.

- Santa Ana Pueblo – Keres speakers.

- Santa Clara Pueblo – Tewa speakers. Built in the 16th century. Located near Española.

- Taos Pueblo – Tiwa speakers. Known for its UNESCO World Heritage Site architecture. Built in the 11th century. It is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the United States.

- Tesuque Pueblo – Tewa speakers. Known for the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and its ceramic Rain God figurines. Located near Santa Fe.

- Zia Pueblo – Keres speakers. Known for their sun symbol, which is on New Mexico's state flag.

- Zuni Pueblo – Zuni speakers. Known for being the first Pueblo visited by the Spanish in 1540.

Arizona Pueblos

- Hopi Tribe – Hopi language speakers.

Texas Pueblos

- Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, El Paso, Texas – Originally Tigua (Tiwa speakers). This Pueblo was created in 1680 after the Pueblo Revolt. About 400 people from Isleta, Socorro, and nearby pueblos were forced or chose to go with the Spanish to El Paso. The Spanish built three missions (Ysleta, Socorro, and San Elizario).

Pueblo Names: Endonyms and Exonyms

Most pueblos today are known by their Spanish or English names. But each Pueblo has its own unique name in its own language. These names (called endonyms) are usually different from the names given by outsiders (called exonyms). This includes names given by speakers of other Puebloan languages. Hundreds of years of trade and marriages between groups are seen in the names given to the same Pueblo in different languages.

The table below shows the names of New Mexican pueblos and Hopi. It uses the official spellings of the languages. Even though Navajo is not a Puebloan language, Navajo names are included. This is because of long contact between them and the Pueblos.

| English/Spanish Name | Endonym | Navajo | Keres | Tewa | Tiwa | Towa | Hopi | Zuni |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acoma | Áakʼu | Haakʼoh | endonym | Téwigeh Ówîngeh | Tʼoławei | Totyagiʼi | Ákookavi | Haku: |

| Cochiti | Kúutyì | Tǫ́ʼgaaʼ | Kʼuuteʼgeh Ówîngeh | Kotəava | Kyʼǽǽtɨɨgiʼi | Kwitsi | Kochudi | |

| Laguna | Kʼáwáiga | Tó Łání | Kʼuʼkwʼáage Ówîngeh | Powhiaba | Kyʼóóweʼegiʼi | Kawaikaʼa | Kʼyanałana | |

| San Felipe | Kaatishtya | Tsédáá’kin | Nąnwheve Ówîngeh | Pʼatəak | Kwilegiʼi | Katistsa | Wepłabattsʼi | |

| Santa Ana | Dámáyá | Dahmi | Shadegeh Ówîngeh | Patuthaa | Tɨ̨́dægiʼi | Tamaya | Damaiya | |

| Kewa/Santo Domingo | Kewa/ Díiwi | Tó Hájiiloh | Taywheve Ówîngeh | Tuwita | Tǽwigiʼi | Tuuwíʼi | Wehkʼyana | |

| Zia | Tsíiyʼa | Tłʼógí | Sia Ówîngeh | Təanąbak | Sæyakwa | Tsiyaʼ | Tsia'a | |

| Nambé | Nąngbeʼe Ôwîngeh | (Not Available) | Nomɨʼɨ | endonym | Nammuluva | Pashiukwa | Tuukwiveʼ Tewa | (Not Available) |

| Pojoaque | Pʼohsųwæ̨geh Ówîngeh | (Not Available) | Pʼohwakedze | Asʼonaʼ | (Not Available) | (Not Available) | (Not Available) | |

| San Ildefonso | Pʼohwhogeh Ówîngeh | Tsétaʼ Kin | Pʼakwede | Pʼahwiaʼhliap | Pʼææshogiʼi | Suustapna Tewa | Dawsa | |

| Ohkay Owingeh/San Juan | Ohkwee Ówîngeh | Kin Łichíí’ | (Not Available) | Pʼakapʼalʼayą | (Not Available) | Yuupaqa Tewa | (Not Available) | |

| Santa Clara | Khaʼpʼoe Ówîngeh | Naashashí | Kaipʼa | Haipaai | Shǽǽpʼæægiʼi | Nasaveʼ Tewa | (Not Available) | |

| Tesuque | Tetsʼúgéh Ówîngeh | Tłʼoh Łikizhí | Tyutsuko | Tutsʼuiba | Tsota | Tuukwiveʼ Tewa | (Not Available) | |

| Isleta | Shiewhibak/ Tsugwevaga | Naatoohó | Dyîiwʼaʼane | Tsiiwheve Ówîngeh | endonym | Téwaagiʼi | Tsiyawipi | Kʼya:shhida |

| Picuris | Pʼįwweltha / Pe’ewi | Tókʼelé | Pikuli | Pʼįnwêê Ówîngeh | Pʼêêkwele | (Not Available) | (Not Available) | |

| Sandia | Ną’piʼąd | Kin Łigaaí | Waashuutsi | Pʼotsą́nûû Ówîngeh | Sądéyagiʼi | Payúpki | We:łuwalʼa | |

| Taos | Təotho | Tówoł | Dâusá | Pʼįnsô Ówîngeh | Yɨ́láta | Kwapihalu | Dopoliana | |

| Jemez | Wâlatɨɨwa | Maʼii Deeshgiizh | Héemʼishiitsi | Wą́ngé Ówîngeh | Híemma | endonym | Hemisi | He:mu:shi |

| Hopi | Móókwi/ Hópi | Ayahkiní | Mùutsi | Khosóʼon | Bukhiek | Hɨ́pé | endonym | Mu:kwi |

| Zuni | Shiwinna | Naashtʼézhí | Sɨ́ɨníitsi | Sųyų | Sunyiʼina | Sɨnigiʼi | Síʼooki | endonym |

| Navajo People | Diné | endonym | Tene | Wǽn Sávo | T’ełiém | Kyʼǽlǽtoosh | Tasavu | A:Machu |

Most Puebloan languages and Navajo use different tones in their words. However, the tone is not always written in the spelling. Some languages show vowel nasalization with a special mark. Ejective consonants (sounds made with a burst of air) are shown with an apostrophe. Long vowels are shown by doubling the letter or adding a colon.

Pueblo Population Over Time

Before Europeans arrived, the Puebloan population might have been as high as 313,000 people. They lived in at least 110 towns. By 1907, their population had dropped to just over 11,300 people. However, since the 20th century, their population has been growing again. As of 2020, there were 78,884 Pueblo people in the USA. About 52,369 of them lived in New Mexico.

See also

In Spanish: Indios pueblo para niños

In Spanish: Indios pueblo para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |