Reception history of Jane Austen facts for kids

The reception history of Jane Austen shows how the books of Jane Austen became famous over time. At first, her books were not widely known. Later, they became very popular. Her novels are now studied a lot. They are also loved by many fans. Jane Austen wrote famous books like Pride and Prejudice (1813) and Emma (1815). She is now one of the most well-known novelists in the English language.

During her life, Austen's books did not make her very famous. Like many women writers then, she published her books secretly. Only people in the aristocracy knew she was the writer. This was an open secret. When her books first came out, high society thought they were fashionable. But they got only a few good reviews. By the mid-1800s, people who knew a lot about literature respected her works. They thought liking her books showed they were clever. In 1870, her nephew wrote Memoir of Jane Austen. This book showed her to more people as "dear, quiet aunt Jane". After this, her books were printed again in popular editions. By the 1900s, many groups formed. Some praised her, and some defended her from the "teeming masses". But they all said they were true Janeites. These were people who truly appreciated Austen.

Early in the 1900s, scholars collected all her works. This was the first time for any British novelist. But it was not until the 1940s that Austen was widely seen as a "great English novelist". In the second half of the 1900s, people started studying Austen more. They studied her works in new ways. For example, they looked at her books artistically, for their ideas, and historically. University English departments grew in the first half of the 1900s. As they grew, studies of Austen split. There were high-level academic studies and popular fan studies. In the late 1900s, fans started Jane Austen societies and clubs. They celebrated Austen, her time, and her books. In the early 2000s, Austen fans supported a big industry. This included printed sequels and prequels. They also supported Austen's work in television and film.

Contents

Jane Austen's Life and Books

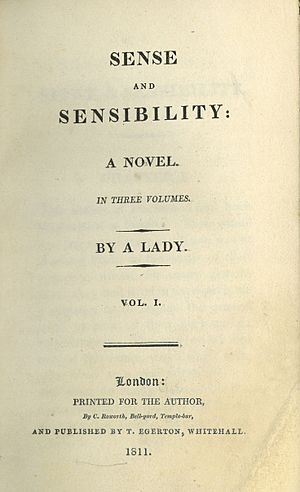

Jane Austen lived her whole life with a large, close family. Her family was part of the lower English gentry. Their support helped her a lot as a writer. For example, Austen read the first versions of her books to her family. They gave her encouragement and help. Her father was the first to try to get her book printed. Austen learned to write from her teenage years until she was about 35. During this time, she tried different literary styles. She tried writing novels using letters, but she did not like it. She wrote and revised three important novels and started a fourth. When Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814), and Emma (1815) were published, she became a successful writer.

However, writing novels was not easy for women in the early 1800s. It made them famous, and people thought it was "unfeminine". So, like many other women writers, Austen published her books secretly. But soon, her writing became an open secret among the aristocracy. On one visit to London, the Prince Regent invited her to his home. His librarian showed her around. He said the Regent liked her books very much. The librarian added that "if Miss Austen had any other Novel forthcoming, she was quite at liberty to dedicate it to the Prince". Austen did not like the prince, who spent a lot of money. She did not want to follow this idea. But her friends convinced her to do it. So, Emma was dedicated to him. Austen later refused the librarian's idea to write a historical romance for the prince's daughter's marriage.

In her last year, Austen revised Northanger Abbey (1817) and wrote Persuasion (1817). She also started another novel, later called Sanditon. She could not finish it before she died. Austen did not see Northanger Abbey or Persuasion published. But her family published them as one book after she died. Her brother Henry wrote a "Biographical Notice of the Author". This short story made people think of Austen as a quiet aunt. She supposedly wrote in her free time. The notice said she did not care about fame or money. It said she would never have put her name on her books. However, Austen's letters show she was excited about publishing her books. She was also interested in how much money they would make. Austen was a professional writer.

Austen's books are known for being very real. They also have sharp comments on society. She used free indirect speech cleverly. Her books are also special for their humor and irony. They made fun of the "novels of sensibility" from the late 1700s. Her works helped change writing towards the realism of the 1800s. As Susan Gubar and Sandra Gilbert explain, Austen laughed at "love at first sight". She also made fun of passion being more important than other feelings or duties. She joked about brave heroes and sensitive heroines. She also made fun of lovers who did not care about money. And she criticized parents who were rude. Austen's stories are funny. But they also show how women depended on marriage. Marriage was important for their social standing and money. She also cared about moral problems, like Samuel Johnson, who influenced her greatly.

Early Reactions to Austen's Books (1812–1821)

Austen's books quickly became popular. Rich people who set fashion and taste especially liked them. Henrietta Ponsonby, Countess of Bessborough, wrote about Sense and Sensibility. She said it was a clever novel. She found it amusing, even though it ended "stupidly". The Prince Regent's 15-year-old daughter, Princess Charlotte Augusta, compared herself to Marianne Dashwood. She said, "I think Marianne & me are very like in disposition". She added that she was not as good, but had the same "imprudence". Pride and Prejudice was enjoyed by Richard Brinsley Sheridan, a play writer. He told a friend to "Buy it immediately" because it was "one of the cleverest things" he had read. Anne Milbanke, who later married Lord Byron, wrote that Pride and Prejudice was "a very superior work". She added that it was "the most probable fiction I have ever read". It had become "at present the fashionable novel". The Dowager Lady Vernon told a friend that Mansfield Park was "Not much of a novel". She said it was "more the history of a family party in the country, very natural". Lady Anne Romilly told her friend, the writer Maria Edgeworth, that Mansfield Park "has been pretty generally admired here". Edgeworth later said that "we have been much entertained with Mansfield Park".

High society liked Austen's novels. But they received few reviews while she was alive. Sense and Sensibility had two reviews. Pride and Prejudice had three. Mansfield Park had none. Emma had seven. Most reviews were short, careful, and positive. They mostly focused on the moral lessons in her books. Brian Southam writes that these reviewers just gave short notes. They added quotes for women readers. These women wanted to know if they would like a book for its story, characters, and morals.

Famous writer Walter Scott wrote the longest and most thoughtful review. Publisher John Murray asked him to review Emma. This review appeared in the Quarterly Review in March 1816. Scott used the review to praise the novel. He praised Austen's skill at showing "nature as she really exists in the common walks of life". He said she showed "a correct and striking representation of that which is daily taking place around him". Modern Austen scholar William Galperin noted that Walter Scott might have been the first to call Austen a great realist writer. This was unlike some of Austen's everyday readers. They saw that she was different from how realistic writing was supposed to be then. Scott wrote in his private journal in 1826 about Austen. This became a famous comparison:

Also read again and for the third time at least Miss Austen's very finely written novel of Pride and Prejudice. That young lady had a talent for describing the involvement and feelings and characters of ordinary life which is to me the most wonderful I ever met with. The Big Bow-wow strain I can do myself like any now going, but the exquisite touch which renders (makes) ordinary commonplace things and characters interesting from the truth of the description and the sentiment is denied to me. What a pity such a gifted creature died so early!

Northanger Abbey and Persuasion were published together in December 1817. They were reviewed in the British Critic in March 1818. They were also reviewed in the Edinburgh Review and Literary Miscellany in May 1818. The reviewer for the British Critic thought Austen's great use of realism showed she had a limited imagination. The reviewer for the Edinburgh Review thought differently. He praised Austen for her "exhaustless invention". He also liked Austen's stories because they mixed familiar scenes with surprising twists. Austen scholars have pointed out that these early reviewers did not know what to think of her works. For example, they did not understand her use of irony correctly. Reviewers thought Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice were stories of good winning over bad.

In the Quarterly Review in 1821, another review came out. Richard Whately was an English writer and theologian. He published the most serious early review of Austen's work. Whately compared Austen to great writers like Homer and Shakespeare. He praised the dramatic quality of her stories. He also said that the novel was a real, respected type of literature. He argued that imaginative stories, especially narratives, were very valuable. He even said they were more important than history or biographies. When done well, like Austen's works, Whately said novels wrote about human experience that readers could learn from. In other words, he believed they were moral. Whately also talked about Austen as a female writer. He wrote: "we suspect one of Miss Austin's [sic] great merits in our eyes to be, the insight she gives us into the peculiarities of female characters. Her heroines are what one knows women must be, though one never can get them to acknowledge (admit) it." No better criticism of Austen was printed until the late 1800s. Whately and Scott started the Victorian era's view of Austen.

Austen's Readers (1821–1870)

Austen had many readers who liked and respected her in the 1800s. According to critic Ian Watt, they liked her careful loyalty to everyday social life. However, Austen's works were not exactly what her Romantic and Victorian British audience liked. They wanted "powerful emotion" shown with lots of sound and color in the writing. Victorian critics and readers liked writers like Charles Dickens and George Eliot. Compared to them, Austen's works seemed small and quiet. Austen's works were printed again starting in late 1832 or early 1833. Richard Bentley printed them in the Standard Novels series. They stayed in print for a long time. But they were not bestsellers. Southam describes her "reading public between 1821 and 1870" as "tiny" compared to the audience for Dickens.

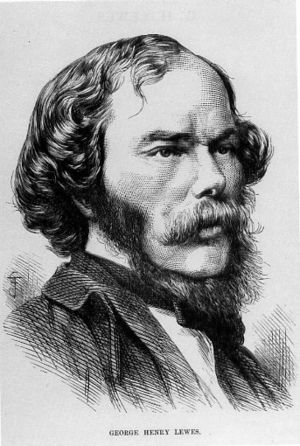

The people who read Austen saw themselves as clever readers. They were the "cultured few". This became a well-known idea in Austen criticism in the 1800s and early 1900s. George Henry Lewes was a philosopher and literary critic. He spoke about this idea in articles in the 1840s and 1850s. "The Novels of Jane Austen" was printed in Blackwood's Magazine in 1859. In it, Lewes praised Austen's books for their "economy of art". He meant she used just enough to get her message across. He also compared her to Shakespeare. He said Austen was not good at making up plots. But he still enjoyed the dramatic feel of her works. He said: "The reader's pulse never throbs, his curiosity is never very strong; but his interest never stops for a moment. The action begins; the people speak, feel, and act; everything that is said, felt, or done tends towards the entanglement or disentanglement of the plot; and we are almost made actors as well as viewers of the little drama."

Writer Charlotte Brontë liked Austen's writing because it was truthful about everyday life. However, Brontë called her "only shrewd (clever) and observant". She said there was not enough passion in her work. To Brontë, Austen's work seemed formal and narrow. In a letter to G.H. Lewes in 1848, Brontë said she did not like Pride and Prejudice. She wrote:

Why do you like Miss Austen so very much? I am puzzled on that point. I read that sentence of yours, and then I got the book. And what did I find? An accurate portrait of a commonplace (everyday) face; carefully fenced, highly cultivated garden, with neat borders and delicate flowers; but no bright, vivid face, no open country, no fresh air, no blue hill, no bonny beck. I should hardly like to live with her ladies and gentlemen, in their elegant but confined houses.

—Charlotte Brontë

Austen's Popularity Grows (1870–1930)

Family Stories

For years, people thought of Austen as Scott and Whately did. Only a few people actually read her novels. In 1870, the first important book about Austen's life, A Memoir of Jane Austen, was written by her nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh. This changed how people thought of Austen. When it was published, Austen's popularity and critical standing grew a lot. The Memoir made people think of an untrained writer who wrote amazing books. People thought Austen was a quiet, middle-aged unmarried aunt. This made her books seem safe for respectable Victorian families to read. The Memoir led to many more printings of Austen's books. The first popular editions came out in 1883. They were a cheap series printed by Routledge. This was followed by editions with pictures, collector's sets, and scholarly editions. However, critics still said that only people who could truly understand the deep meaning of Austen's books should read them. But after the Memoir was printed, much more criticism about Austen was published. More came out in two years than had come out in the last 50 years.

In 1913, William Austen-Leigh and Richard Arthur Austen-Leigh printed a family biography. It was called Jane Austen: Her Life and Letters—A Family Record. William and Arthur were both part of the Austen family. It was based mostly on family papers and letters. Austen biographer Park Honan describes it as "accurate, steady, reliable, and at times vivid and suggestive". The authors moved away from the emotional tone of the Memoir. But they did not go much beyond the family records and traditions. So, their book offers only facts. It does not offer much interpretation.

New Ways of Thinking About Austen

In the late 1800s, the first critical books about Austen's works were printed. In 1890, Godwin Smith printed the Life of Jane Austen. This started a "fresh phase in the critical heritage". This began "formal (official) criticism". People began focusing on Austen as a writer. They started to analyze what made her writing special. Southam said there was much more Austen criticism around 1780. He also said that the reviews became better. However, he was bothered by a "certain uniformity" in them:

We see the novels praised for their elegant form and their surface 'finish'; for the realism of their fictional world, the variety and strength of their characters; for their widespread humor; and for their gentle and undogmatic morality and its unsermonising delivery. The novels are prized for their 'perfection'. Yet it is seen to be a narrow perfection, achieved within the bounds of domestic comedy.

Richard Simpson, Margaret Oliphant, and Leslie Stephen were some of the best reviewers. In a review of the Memoir, Simpson said Austen was a serious but ironic critic of English society. He started two ideas for understanding her: using humor to criticize society, and irony as a way to study morals. He continued Lewes's comparison to Shakespeare. He wrote that Austen:

began by being an ironical critic; she showed her judgment not by direct criticism, but by imitating and exaggerating the faults of her models. Criticism, humor, irony, the judgment not of one that gives sentence but of the mimic who quizzes while he mocks, are her characteristics.

Simpson's essay was not well-known. It did not have much influence until Lionel Trilling quoted it in 1957. Margaret Oliphant was another important writer whose criticism of Austen did not have much influence. She described Austen as "armed with a 'fine vein of feminine cynicism,' 'full of subtle power, keenness, finesse, and self-restraint (control),' with an 'exquisite sense' of the 'ridiculous,' 'a fine stinging yet soft-voiced contempt,' whose works are very 'calm and cold and keen'". This kind of criticism was not fully developed until the 1970s. This was when feminist literary criticism began.

Austen's works had been printed in the United States from 1832. However, it was only after 1870 that Americans began seriously thinking about Austen's works. As Southam says, "for American literary nationalists Jane Austen's cultivated scene was too pale, too constrained, too refined, too downright unheroic". Austen was not democratic enough for Americans. Also, her books did not have the frontier themes often seen in American literature. How Americans thought about Austen was shown in an argument between William Dean Howells and Mark Twain. Through his essays, Howells helped make Austen much more popular. Twain, however, used Austen to argue against the English tradition in America. In his book Following the Equator, Twain described the library on his ship: "Jane Austen's books are absent from this library. Just that one omission alone would make a fairly good library out of a library that hadn't a book in it."

The Rise of Janeites

| "Might we not borrow from Miss Austen's biographer the title which the affection of a nephew bestows upon (gives) her, and recognise her officially as 'dear aunt Jane'?" |

| — Richard Simpson |

The Encyclopædia Britannica changed how they described Austen as she became more popular. The eighth edition (1854) called her "an elegant novelist". The ninth edition (1875) praised her as "one of the most distinguished (remarkable) modern British novelists". Austen novels began to be studied at universities. Her works also began to appear in histories of the English novel. Most people still thought of her as "dear aunt Jane". This was how she was first presented in the Memoir. Howells had made this picture of Austen famous with his essays in Harper's Magazine. Writer and critic Leslie Stephen described a craze for Austen that grew in the 1880s as "Austenolatry". It was only after the Memoir was printed that readers grew to like Austen as a person. Before then, literary experts had said their enjoyment of Austen showed how clever they were. However, around the 1990s, they became worried about how popular Austen's works became. They started calling themselves Janeites. They wanted to show they were different from people they thought did not understand Austen properly.

American novelist Henry James liked Austen. He once said she was as great as Shakespeare, Cervantes, and Henry Fielding. He called them "the fine painters of life". But James thought Austen was an "unconscious" artist. He said she was "instinctive and charming". In 1905, James said he did not like the public interest in Austen. He said it was more than Austen's "intrinsic merit (worth) and interest" deserved. James said this was mostly because of the "stiff breeze of the commercial" world. He meant publishers, editors, illustrators, and magazine producers. They found "dear Jane" useful for making money. They could reproduce her books in many "tasteful" and "salable" forms.

Reginald Farrer, a British travel writer, did not like the emotional image of "Aunt Jane". Instead, he wanted to study Austen's fiction in a new way. In 1917, he published a long essay in the Quarterly Review. Jane Austen scholar A. Walton Litz called it the best single introduction to her works. Southam calls it a "Janeite" piece without the worship. Farrer claimed that Jane Austen was not unconscious (disagreeing with James). He said that she was a writer who focused deeply and was a sharp critic of her society. He called her "radiant and remorseless", "dispassionate yet pitiless". He said she had "the steely quality, the incurable rigor of her judgment". Farrer was one of the first critics who saw Austen as a "subversive" writer.

Modern Studies of Austen (1930–2000)

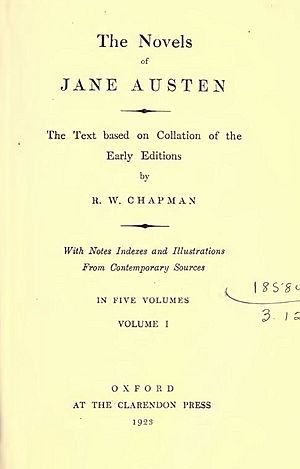

Important early works helped Austen become well accepted in universities. The first was Oxford Shakespearean scholar Andrew Cecil Bradley's 1911 essay. This essay is "generally (largely) regarded (seen) as the starting-point for the serious academic approach to Jane Austen". Bradley pointed out Austen's ties to 1700s critic and writer Samuel Johnson. He argued that she was a moralist as well as a humorist. According to Southam, this argument was "totally (completely) original". Bradley separated Austen's works into "early" and "late" novels. Scholars still separate Austen's works as Bradley did today. The second original early-1900s critic of Austen was R. W. Chapman. His edition of Austen's works was the first scholarly edition of any English novelist's works. The Chapman edition has been the basis for all editions of Austen's works since then.

After Bradley and Chapman, Austen studies grew very quickly in the 1920s. British writer E. M. Forster used Austen's works for his idea of the "round" character. This means a character that is complex and changes. The academic study of her works became mature with the 1939 book Jane Austen and Her Art by Mary Lascelles. This was "the first full-scale historical and scholarly study" of Austen. Lascelles included a short essay about her. She also studied the books Austen read and how they influenced her writing. And she studied Austen's style and "narrative art". Lascelles felt that earlier critics had worked in a way "so small that the reader does not see how they have reached their conclusions". She wanted to study all of Austen's works, style, and techniques together. Critics after Lascelles agreed that she studied them well. Lascelles was interested in Austen's connection to Samuel Johnson. She also liked Austen's wish to discuss morality through fiction. In this, she was much like Bradley before her. But around this time, some Austen fans began to worry. They feared her works were being enjoyed by only a few people. They were afraid that Austen was being criticized only by academics. This argument continued into the 2000s.

In the mid-1900s, new ways of looking at Austen became popular. Scholars started studying Austen more skeptically. D. W. Harding, adding to Farrer's ideas, wrote an essay called "Regulated Hatred: An Aspect of the Work of Jane Austen". He argued that Austen did not support society's customs. He said her irony was not funny but bitter. He also claimed that Austen wanted to show the faults of the society she wrote about. Through her irony, Austen tried to protect herself as an artist and a person. She protected herself from the behavior and practices she disliked. Almost at the same time, British critic Q. D. Leavis printed "Critical Theory of Jane Austen's Writing" in Scrutiny in the early 1940s. In it, Leavis argued that Austen was a professional, not an amateur (untrained), writer. Harding's and Leavis's articles were followed by Jane Austen: Irony as Defense and Discovery (1952). This was written by Martin Mudrick. He saw Austen as lonely, defensive, and critical of her society. He carefully described how Austen felt about the literature of her time. He also showed how she used irony to show the difference between how society was and how she thought it could be. An important British critic, F. R. Leavis, said in The Great Tradition (1948) that Austen was one of the great writers of English fiction. Ian Watt agreed. He helped shape the arguments about the genre of the novel. These new views and Leavis's words helped Austen gain a great reputation among academics. They agreed that she "combined (put together) Henry Fielding's and Samuel Richardson's qualities of inner thoughts and irony, realism and satire". They said she was a better author than both.

After the Second World War, people began studying Austen more deeply and in different ways. Many people have studied Austen as a political writer. Critic Gary Kelly explains, "Some see her as a political 'conservative' because she seems to defend the established social order. Others see her as sympathetic to 'radical' politics that challenged the established order, especially in the form of patriarchy. Some critics see Austen's novels as complex. They criticize parts of the social order but support stability and an open class hierarchy." In Jane Austen and the War of Ideas (1975), Marilyn Butler argues that Austen was greatly influenced by the main moral and political arguments of her time. She says Austen had a strong, conservative, and Christian view in these arguments. Alistair M. Duckworth in The Improvement of the Estate: A Study of Jane Austen's Novels (1971) argues that Austen used the idea of the "estate" to symbolize all that was important about English society. He said it should be kept, improved, and passed down to future generations. As Rajeswari Rajan notes, "the idea of a political Austen is no longer seriously challenged". The questions scholars now study include: "the Revolution, war, nationalism, empire, class, 'improvement' [of the estate], the clergy, town versus (against) country, abolition, the professions, female emancipation". They also ask if her politics were Tory, Whig, or radical. And if she was a conservative or a revolutionary, or somewhere in between.

| "... in all her novels Austen examines the female powerlessness (weakness) that underlies pressure to marry, the unfairness of inheritance laws, the ignorance of women denied (not given) formal (official) education, the psychological danger of the heiress or widow, the exploited dependency of the spinster, the boredom of the lady provided with vocation" |

| — Gilbert and Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic (1979) |

In the 1970s and 1980s, Austen studies were influenced by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar's The Madwoman in the Attic (1979). This book looks at the "explosive anger" of 1800s female English writers hidden under their "proper surfaces". This work, along with other feminist criticism of Austen, made people see her as a woman writer. The interest these critics showed in Austen led people to discover and study other women writers from Austen's time. Also, when Julia Prewitt Brown's Jane Austen's Novels: Social Change and Literary Form (1979), Margaret Kirkham's Jane Austen: Feminism and Fiction (1983), and Claudia L. Johnson's Jane Austen: Women, Politics and the Novel (1988) were printed, scholars could no longer argue that Austen was firmly "apolitical, or even 'conservative'". Kirkham, for example, said that Austen's ideas and those of Mary Wollstonecraft were quite similar. She called them both "Enlightenment feminists". Johnson also places Austen in an 1700s political tradition. However, she notes the influence Austen received from the political novels of the 1790s written by women.

In the late 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, studies of Austen were mostly about ideas, postcolonialism, and Marxist criticism. Edward Said wrote a chapter in his book Culture and Imperialism (1993) about Mansfield Park. He argued that the small role of "Antigua" and slavery showed that colonial oppression was an unspoken idea in English society in the early 1800s. This caused a lot of debate. In Jane Austen and the Body: 'The Picture of Health', (1992) John Wiltshire looked at how much Austen's characters cared about illness and health. There has also been a return to thinking about aesthetics (beauty in art). D. A. Miller's Jane Austen, or The Secret of Style (2003) connects artistic concerns with queer theory.

Images for kids

-

Novelist Walter Scott praised Austen's "exquisite touch which renders ordinary commonplace things ... interesting".

-

George Henry Lewes, partner of George Eliot, compared Austen to Shakespeare.

-

Modern scholars emphasised Austen's intellectual and artistic ties to important 18th-century figures such as Samuel Johnson.

-

The Jane Austen Centre in Bath, a place of pilgrimage for Janeites

-

Greer Garson as Elizabeth Bennet in the 1940 Pride and Prejudice, the first feature film adaptation of the novel

See also

In Spanish: Historia sobre la recepción de los libros de Jane Austen para niños

In Spanish: Historia sobre la recepción de los libros de Jane Austen para niños