Romanticism in Scotland facts for kids

Romanticism in Scotland was a big movement in art, writing, and ideas. It happened mostly between the late 1700s and early 1800s. This movement was part of a larger one across Europe. It was a bit of a reaction against the Age of Enlightenment, which focused a lot on logic and reason.

Romanticism, instead, highlighted feelings, individual experiences, and national pride. It looked back to the Middle Ages for inspiration, moving away from older Renaissance and Classicist styles. In Scotland, experts like Ian Duncan and Murray Pittock have shown that Scottish Romanticism had its own special flavor. It used the Scots language, created a heroic national history, and showed a unique Scottish identity.

In art and literature, Romanticism brought back the mythical bard Ossian. It also celebrated Scottish poetry through Robert Burns and historical novels by Walter Scott. Scott also greatly influenced Scottish plays. Art began to show the Scottish Highlands as a wild and beautiful place. Scott's rebuilding of Abbotsford House started a trend for the Scots Baronial style in architecture. In music, Burns helped create a collection of Scottish songs, mixing them with classical music. Romantic music became very popular in Scotland and stayed that way into the 1900s.

Intellectually, Scott and thinkers like Thomas Carlyle helped shape how history was written and imagined. Romanticism also affected science, especially life sciences, geology, and astronomy. This made Scotland important in these fields for a long time. Scottish philosophy was mostly about Scottish Common Sense Realism, which shared some ideas with Romanticism. It also influenced Transcendentalism in America. Scott also played a big role in shaping Scottish and British politics, creating a romantic image of Scotland that changed its national identity.

Romanticism started to fade in the 1830s. However, it kept influencing things like music until the early 1900s. It also left a lasting mark on what it means to be Scottish and how others see Scotland.

Contents

What Was Romanticism?

Romanticism was a complex movement in art, writing, and ideas. It began in the late 1700s in Western Europe. It grew stronger during and after the Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution. It was partly a rebellion against the strict rules of the Age of Enlightenment, which tried to explain nature with pure logic.

Romanticism was strongest in visual arts, music, and literature. But it also greatly influenced history, philosophy, and science. In Scotland, some argue that Romanticism actually continued some ideas from the Enlightenment.

Romanticism is often seen as bringing back the spirit of the Middle Ages. It went beyond strict, logical styles to celebrate medieval art and stories. People wanted to escape the problems of growing cities and industries. They embraced things that were exotic, new, and from far away.

This movement is also linked to political revolutions. These include the American Revolution, the French Revolution, and movements for independence in places like Poland and Greece. Romanticism often involved strong emotions and a focus on individual experience. It also had a sense of the grand and amazing in nature. It emphasized imagination, beautiful landscapes, and a spiritual connection with nature.

Literature and Plays

After Scotland joined England in 1707, it started using more English language and culture. However, Scottish literature kept its own identity and became famous worldwide. Allan Ramsay (1684–1758) helped bring back interest in older Scottish writing. He also started a trend for nature poetry.

James Macpherson (1736–96) was the first Scottish poet to become internationally famous. He claimed to have found poems by an ancient bard named Ossian. He published "translations" that became very popular around the world. People called them a Celtic version of the great Classical epics. His work Fingal (1762) was quickly translated into many European languages. It helped start the Romantic movement in Europe, especially in Germany. Even Napoleon liked it in France. Later, it became clear that the poems were not direct translations. They were flowery adaptations to fit what people wanted to read.

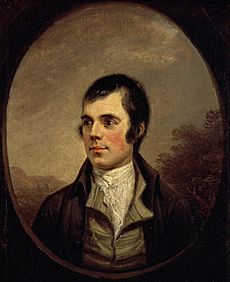

Robert Burns (1759–96) and Walter Scott (1771–1832) were greatly influenced by the Ossian poems. Burns, a poet and songwriter from Ayrshire, is seen as Scotland's national poet. He had a big impact on the Romantic movement. His song "Auld Lang Syne" is sung at Hogmanay (New Year's Eve). "Scots Wha Hae" was an unofficial national anthem for a long time.

Scott started as a poet and collected Scottish ballads. His first novel, Waverley (1814), is often called the first historical novel. It began a very successful career. He wrote other historical novels like Rob Roy (1817) and Ivanhoe (1820). Scott probably did more than anyone else to define and popularize Scottish culture in the 1800s. Other important writers of this time include James Hogg (1770–1835) and John Galt (1779–1839).

Scotland also had two very important literary magazines: The Edinburgh Review (started 1802) and Blackwood's Magazine (started 1817). These magazines greatly influenced British literature during the Romantic era. Experts suggest that Scott's novels and these magazines made Edinburgh a cultural center. It became central to a wider "British Isles nationalism."

Scottish "national drama" appeared in the early 1800s. Plays with Scottish themes became very popular on stage. The Church of Scotland had discouraged theatres, and there were fears of Jacobite gatherings. In the late 1700s, many plays were written for small amateur groups. Most of these plays were never published and are now lost. Later, there were "closet dramas" meant to be read, not performed. These included works by Scott, Hogg, and Joanna Baillie (1762–1851). They were often inspired by old ballads and Gothic Romanticism.

The Scottish national drama of the early 1800s was mostly historical. Many plays were adaptations of Scott's Waverley novels. Older Scottish plays included Shakespeare's Macbeth and John Home's Douglas. Scott was very interested in theatre and became a shareholder in the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh. Baillie's play The Family Legend, set in the Highlands, was first performed in Edinburgh in 1810. Scott helped with this, trying to encourage Scottish drama.

Scott also wrote five plays himself. Hallidon Hill (1822) was a patriotic Scottish history. Adaptations of the Waverley novels were very popular. Rob Roy was performed over 1,000 times in Scotland. These popular plays attracted more people to the theatre. They helped shape how people enjoyed plays in Scotland for the rest of the century.

Art and Landscapes

The Ossian stories became a popular topic for Scottish artists. Artists like Alexander Runciman (1736–85) and David Allan (1744–96) created works based on these tales. During this time, attitudes towards the Highlands changed. People used to see them as wild, empty places with backward people. Now, they were seen as beautiful examples of nature, with strong, primitive inhabitants. These people were shown in a dramatic way.

Jacob More's (1740–93) paintings of "Falls of Clyde" (1771–73) showed the waterfalls as a "natural national monument." This was an early example of a romantic feeling towards the Scottish landscape. Runciman was probably the first artist to paint Scottish landscapes using watercolors in the new romantic style.

The influence of Romanticism can also be seen in the works of artists from the late 1700s and early 1800s. These include Henry Raeburn (1756–1823) and Alexander Nasmyth (1758–1840). Raeburn was the most important artist of this time to work his whole career in Scotland. He was famous for his portraits of important Scottish people. He added Romantic elements to traditional portrait painting. He became a knight in 1822.

Nasmyth worked in London and visited Italy, but he returned to Edinburgh for most of his career. He painted many types of works, including his portrait of Robert Burns against a dramatic Scottish background. Nasmyth is known as "the founder of the Scottish landscape tradition." The work of John Knox (1778–1845) continued the landscape theme. He directly linked it to Scott's Romantic works. He was also one of the first artists to paint the city of Glasgow.

Architecture and Castles

The Gothic revival in architecture was a big part of Romanticism. The Scots Baronial style was a Scottish version of Gothic. Some of the earliest examples of Gothic revival architecture are from Scotland. Inveraray Castle, built from 1746, included turrets in a traditional Palladian-style house.

A very important building for the return of the Scots Baronial style in the early 1800s was Abbotsford House. This was Walter Scott's home. It was rebuilt for him starting in 1816 and became a model for the style. Common features borrowed from 16th and 17th-century houses included battlemented gateways, crow-stepped gables, pointed turrets, and machicolations.

This style became popular across Scotland. Architects like William Burn (1789–1870) and David Bryce (1803–1876) used it for many homes. Examples in cities include Cockburn Street in Edinburgh (from the 1850s) and the National Wallace Monument at Stirling (1859–69). The rebuilding of Balmoral Castle as a baronial palace, and Queen Victoria using it as a royal retreat from 1855–58, made the style even more popular.

In church architecture, a style similar to England's was adopted. Important architects included Frederick Thomas Pilkington (1832–98). He created a new church style that fit the popular High Gothic but adapted it for the Free Church of Scotland. An example is Barclay Viewforth Church, Edinburgh (1862–64). Robert Rowand Anderson (1834–1921) designed many important public and private buildings in Scotland. These include the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and the Central Hotel at Glasgow Central station.

Music and Songs

One key part of Romanticism was creating national art music. In Scotland, this type of music was very popular from the late 1700s to the early 1900s. In the 1790s, Robert Burns tried to create a collection of Scottish national songs. He built on the work of people who studied old things, like William Tytler.

Burns worked with music publisher James Johnson on the Scots Musical Museum. This collection was published in six volumes between 1787 and 1803. Burns wrote about a third of the songs. Burns also worked with George Thomson on A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs. This collection, published from 1793 to 1818, adapted Scottish folk songs with classical arrangements. Thomson was inspired by Scottish songs sung by Italian performers in Edinburgh. He collected Scottish songs and got famous European composers like Joseph Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven to arrange them. Burns edited the lyrics.

A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs helped make Scottish songs part of European classical music. Thomson's work brought Romantic elements, like Beethoven's harmonies, into Scottish classical music. Walter Scott also collected and published Scottish songs. His first literary work was Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802–03). This collection first made his work known to an international audience. Some of his lyrics were set to music by Schubert.

Perhaps the most important composer of the early 1800s was the German Felix Mendelssohn. He visited Britain ten times starting in 1829. Scotland inspired two of his most famous works: the overture Fingal's Cave and the Scottish Symphony. On his last visit in 1847, he conducted his Scottish Symphony for Queen Victoria. Max Bruch (1838–1920) composed the Scottish Fantasy (1880) for violin and orchestra. It includes a tune used in Burns's song Scots Wha Hae.

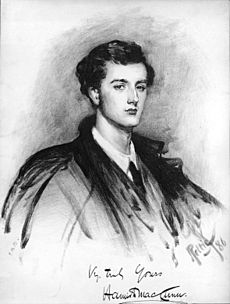

By the late 1800s, Scotland had its own national style of orchestral and opera music. Important composers included Alexander Mackenzie (1847–1935) and Hamish MacCunn (1868–1916). Mackenzie mixed Scottish themes with German Romanticism. He is known for his Scottish Rhapsodies and the Scottish Concerto for piano. MacCunn's works, like his overture The Land of the Mountain and the Flood (1887) and his opera Jeanie Deans (1894), are seen as the musical version of famous Scottish buildings like Abbotsford and Balmoral.

History Writing

Enlightenment historians tried to find general lessons about humanity from history. In contrast, the German philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder introduced the idea of Volksgeist (a unique national spirit) that drove historical change. Because of this, a key part of Romanticism's influence was the creation of national histories.

An important part of Scottish national history was an interest in old things. People like John Pinkerton (1758–1826) collected ballads, coins, songs, and artifacts. Enlightenment historians often felt embarrassed by Scottish history, especially the Middle Ages and the Reformation. But many historians in the early 1800s started to study these areas seriously.

Lawyer and expert on old things, Cosmo Innes, wrote about Scotland in the Middle Ages (1860). Patrick Fraser Tytler's nine-volume history of Scotland (1828–43) was very important. He had a sympathetic view of Mary, Queen of Scots. Tytler helped found the Bannatyne Society in 1823 with Scott. This society helped historical research in Scotland. Thomas M'Crie's (1797–1875) biographies of John Knox and Andrew Melville helped improve their reputations.

One of the most important thinkers linked to Romanticism was Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881). He was born in Scotland but lived in London. He helped introduce German Romantic writers like Schiller and Goethe to British readers. Carlyle was an essayist and historian. He invented the phrase "hero-worship," praising strong leaders like Oliver Cromwell. His book The French Revolution: A History (1837) showed the struggles of the French aristocracy. He believed history was a force that couldn't be stopped.

Carlyle, along with French historian Jules Michelet, used "historical imagination." This meant inviting readers to feel for historical figures and even imagine talking to them. Unlike many European Romantic historians, Carlyle was often pessimistic about human nature. He believed history could show patterns for the future.

Romantic writers often disagreed with the fact-based history of the Enlightenment. They preferred "poet-historians" who would use their insight to create more than just lists of facts. For this reason, historians like Thierry saw Walter Scott as an authority in history writing. Scott spent a lot of effort finding new documents for his novels. Scott is now mostly seen as a novelist, but he also wrote a nine-volume biography of Napoleon. He is described as a "towering figure of Romantic historiography." He greatly influenced how history, especially Scottish history, was understood.

Science and Discovery

Romanticism also affected how science was explored. Romantic views on science varied. Some distrusted science, while others supported a non-mechanical science that rejected abstract theories. Major trends in European science linked to Romanticism included Naturphilosophie, which focused on reuniting humans with nature. Another was Humboldtian science, which emphasized careful observation, accurate tools, and working in nature. Romantic scientists often preferred areas where observation was key, like life sciences, geology, and astronomy.

James Allard points to the origins of Scottish "Romantic medicine" in the work of Enlightenment figures. These included the brothers William (1718–83) and John Hunter (1728–93). They were leading anatomists and surgeons. Edinburgh was also a major center for medical teaching. Key figures influenced by the Hunters and Romanticism include John Brown (1735–88) and John Barclay (1758–1826). Brown argued that life was a "vital energy." This idea was very influential, especially in Germany.

The University of Edinburgh also supplied many surgeons for the royal navy. Robert Jameson (1774–1854), a professor there, made sure many of these were surgeon-naturalists. These scientists were important in exploring nature worldwide. They included Robert Brown (1773–1858), a key figure in exploring Australia. He is credited with discovering the cell nucleus and observing Brownian motion. Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology (1830) is often seen as the start of modern geology. It relied on careful measurements, a key idea from Humboldtian science.

Romantic thinking was also clear in the writings of Hugh Miller, a stonemason and geologist. He believed nature was a planned progression towards humans. Publisher and scientist Robert Chambers (1802–71) became a friend of Scott. His most important work was Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844). This book was the most complete argument for evolution before Charles Darwin's work.

David Brewster (1781–1868), a physicist and astronomer, did important work in optics. His work was important for later discoveries in biology, geology, and astronomy. Thomas Henderson (1798–1844) made observations in South Africa that allowed him to be the first to calculate the distance to Alpha Centauri. He then became the first Astronomer Royal for Scotland in 1834. Mary Somerville (1780–1872), a mathematician and astronomer, was influenced by Humboldt. She was one of the few women recognized in science at that time.

Politics and Identity

After the Jacobite uprisings, the British government passed laws to break down the clan system. These laws banned carrying weapons and wearing tartan. Most of these laws were removed by the late 1700s as the Jacobite threat ended.

Soon after, Highland culture was brought back into favor. Tartan was already used for Highland regiments in the British army. But by the 1800s, ordinary people in the Highlands had mostly stopped wearing it. In the 1820s, tartan and the kilt were adopted by rich people across Europe. The international craze for tartan and the romantic idea of the Highlands started with the Ossian poems. Walter Scott made it even more popular.

Scott arranged the royal visit of King George IV to Scotland in 1822. The king wore tartan, which caused a huge demand for kilts and tartans. This demand was so big that Scottish linen makers couldn't keep up. Individual clan tartans were mostly defined during this time. They became a major symbol of Scottish identity. This "Highlandism," where all of Scotland was identified with Highland culture, was made stronger by Queen Victoria's interest in the country. She made Balmoral her royal retreat and loved "tartanry."

The romantic view of the Highlands and the acceptance of Jacobitism into mainstream culture helped calm tensions about Scotland's place in the Union with England. In many countries, Romanticism played a big part in starting independence movements by developing national identities. Some argue that Romanticism in Scotland did not lead to a strong cultural nationalism that could be passed to the working classes. Others suggest that there was a Scottish nationalism, but it was expressed as "Unionist nationalism."

A form of political radicalism remained within Scottish Romanticism. It appeared in groups like the Society of the Friends of the People in 1792. However, Scottish identity did not become a strong movement for independence until the 1900s.

Philosophy and Ideas

The main philosophy in Scotland in the late 1700s and early 1800s was Scottish Common Sense Realism. This idea said that some concepts are built into us. These include our own existence, the existence of objects, and basic moral rules. All other arguments and moral systems must come from these basic ideas. It was an attempt to combine new scientific discoveries with religious belief.

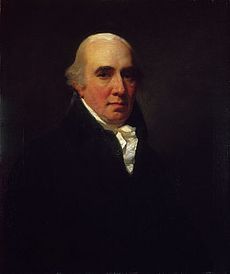

This way of thinking started as a reaction to the scepticism that was popular during the Enlightenment. Especially the ideas of Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711–76). This philosophy was first written down by Thomas Reid (1710–96) in his book An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense (1764). It was made popular in Scotland by people like Dugald Stewart (1753–1828). Stewart's students included Walter Scott. This philosophy later greatly influenced Charles Darwin.

Common Sense Realism was not only important in Scotland but also had a big impact in France, the United States, and Germany. Victor Cousin (1792–1867) was its most important supporter in France. He became Minister of Education and included the philosophy in school lessons. In Germany, the focus on careful observation influenced Alexander von Humboldt's ideas about science. It was also a major factor in the development of German Idealism.

James McCosh (1811–94) brought Common Sense Realism from Scotland to North America in 1868. He became president of Princeton University, which became a strong supporter of the movement. Noah Porter (1811–92) taught Common Sense Realism to many students at Yale. As a result, it greatly influenced Transcendentalism in New England, especially in the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–82).

When Romanticism Faded

In literature, Romanticism is often thought to have ended in the 1830s. Some say it was over by 1848. However, Romanticism lasted much longer in some places and areas, especially in music, where it continued from 1820 to 1910. The death of Walter Scott in 1832 is seen as the end of the great Romantic generation. After this, Scottish literature and culture became less famous internationally. Scott's reputation as a writer also declined in the late 1800s, only getting better in the 1900s.

Changes in economy and society, like better travel by railways, made it harder for Edinburgh to be a cultural capital like London. Its publishing industry moved to London. A lack of opportunities in politics and writing led many talented Scots to leave for England and other places. The sentimental "Kailyard" tradition of writers like J. M. Barrie was seen by some as "sub-romantic."

In art, Scottish landscape painting continued into the late 1800s. But Romanticism gave way to influences like French Impressionism and later Modernism. The Scots Baronial style remained popular until the end of the 1800s. Although Romanticism lasted longer in music, it went out of style in the 1900s.

The idea of historical imagination was replaced by a focus on facts and sources. After Scott's death, Scottish national history lost its energy. The Scottish writers stopped writing Scottish histories. In science, the fast growth of knowledge led to more specialization. The "man of letters" (a person knowledgeable in many fields) and amateur scientists, who were common in Romantic science, became less important. Common Sense Realism began to decline in Britain.

Lasting Influence

Scotland can claim to have helped start the Romantic movement with writers like Macpherson and Burns. In Scott, it produced a figure of international fame. His invention of the historical novel influenced writers worldwide. These included Alexandre Dumas in France and Leo Tolstoy in Russia.

The tradition of Scottish landscape painting greatly influenced art in Britain and elsewhere. Artists like J. M. W. Turner took part in the growing Scottish "grand tour." The Scottish Baronial style influenced buildings in England. It was also taken by Scots to North America, Australia, and New Zealand. In music, the early efforts of people like Burns, Scott, and Thomson helped bring Scottish music into European classical music. Later composers like MacCunn contributed to a British revival of interest in classical music.

The idea of history as a powerful force and the Romantic idea of revolution greatly influenced American writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson. Romantic science helped Scotland keep the importance and good reputation it gained during the Enlightenment. It also helped develop many new fields of study, like geology and biology. Some believe the 1800s were "the century of Scottish science."

Politically, Romanticism, as pursued by Scott, helped ease some of the tension about Scotland's place in the Union. But it also helped keep a common and distinct Scottish national identity alive. This identity would become a major factor in Scottish politics from the second half of the 1900s. Today, modern images of Scotland around the world – its landscape, culture, science, and arts – are still largely shaped by the ideas created and made popular by Romanticism.

Images for kids

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |