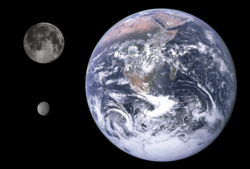

Umbriel facts for kids

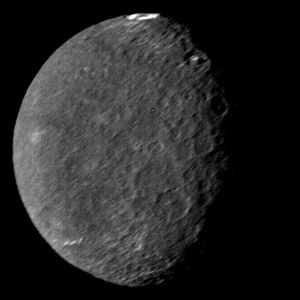

Grayscale image of Umbriel from Voyager 2, January 1986. Umbriel's surface is heavily battered; the bright crater Wunda can be seen at the top of the image.

|

|||||||||

| Discovery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovered by | William Lassell | ||||||||

| Discovery date | October 24, 1851 | ||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||

| MPC designation | Uranus II | ||||||||

| Adjectives | Umbrielian | ||||||||

| Orbital characteristics | |||||||||

| 266000 km | |||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.0039 | ||||||||

| 4.144 d | |||||||||

|

Average orbital speed

|

4.67 km/s (calculated) | ||||||||

| Inclination | 0.128° (to Uranus's equator) | ||||||||

| Satellite of | Uranus | ||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||

|

Mean diameter

|

1,169.4±5.6 km | ||||||||

|

Mean radius

|

584.7±2.8 km (0.092 Earths) | ||||||||

| 4296000 km2 (0.008 Earths) | |||||||||

| Volume | 837300000 km3 (0.0008 Earths) | ||||||||

| Mass | (1.2885±0.0225)×1021 kg | ||||||||

|

Mean density

|

1.539 g/cm3 (calculated) | ||||||||

| 0.196 m/s2 (~0.0257 g) | |||||||||

| 0.542 km/s | |||||||||

| presumed synchronous | |||||||||

| 0 | |||||||||

| Albedo |

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||

| 15.1 | |||||||||

| Atmosphere | |||||||||

|

Surface pressure

|

zero (presumed to be extremely low) | ||||||||

Umbriel is the third-largest moon of Uranus. It was found on October 24, 1851, by William Lassell. He discovered it at the same time as another moon, Ariel. Umbriel got its name from a character in a poem called The Rape of the Lock by Alexander Pope.

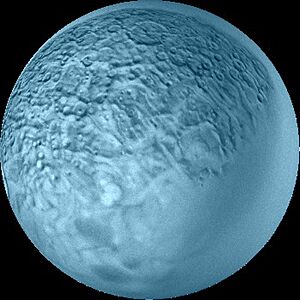

This moon is mostly made of ice, but it also has a good amount of rock. Scientists think it might have layers, like a rocky center (called a core) and an icy outer layer (called a mantle). Umbriel's surface is the darkest of all the moons orbiting Uranus. It looks like its surface was mostly shaped by things hitting it, like space rocks. However, some deep valleys (canyons) suggest that processes inside the moon also changed it long ago.

Umbriel has many impact craters, some as big as 210 kilometers (130 miles) wide. It is the second most cratered moon of Uranus, after Oberon. The most noticeable feature on its surface is a bright ring inside a crater called Wunda. Like other major moons of Uranus, Umbriel likely formed from a disk of material around Uranus when the planet was new. The Voyager 2 spacecraft is the only one that has studied Umbriel up close. In January 1986, it took pictures that mapped about 40% of the moon's surface.

Contents

Discovering Umbriel and Its Name

Umbriel was discovered by William Lassell on October 24, 1851. He found it along with another moon of Uranus, Ariel. Before this, William Herschel (who found Titania and Oberon) thought he saw four more moons of Uranus in the late 1700s. But his observations were never proven, and those objects are now thought to be mistakes.

All of Uranus's moons are named after characters from plays by William Shakespeare or poems by Alexander Pope. John Herschel, William Herschel's son, suggested the names for the four known moons of Uranus in 1852. He did this at Lassell's request. It's not fully clear if John Herschel came up with the names himself or if Lassell did and then asked for John Herschel's approval.

Planetary moons, other than Earth's Moon, usually don't have special symbols in astronomy. A software engineer named Denis Moskowitz suggested a symbol for Umbriel. It combines the letter U (for Umbriel) with a part of Uranus's symbol. However, this symbol is not widely used.

How Umbriel Orbits Uranus

Umbriel orbits Uranus about 266,000 kilometers (165,000 miles) away. This makes it the third farthest moon from Uranus among its five main moons. Umbriel's path around Uranus is almost a perfect circle, and it's not tilted much compared to Uranus's equator.

It takes Umbriel about 4.1 Earth days to go around Uranus once. This is the same amount of time it takes for Umbriel to spin once. This means Umbriel is "tidally locked" to Uranus. Just like Earth's Moon, Umbriel always shows the same side to its planet.

Umbriel's orbit is completely inside Uranus's magnetic field. This is important because the side of Umbriel that trails behind it (the "trailing hemisphere") gets hit by charged particles from Uranus's magnetic field. These particles spin along with Uranus. This bombardment might make the trailing sides of moons darker. This darkening is seen on all Uranian moons except Oberon. Umbriel also absorbs these charged particles, which causes a drop in particle count near its orbit, as seen by Voyager 2.

Uranus orbits the Sun almost on its side. Its moons orbit in the same flat plane as Uranus's equator. This means Umbriel and the other moons have very extreme seasons. Both the northern and southern poles spend 42 years in total darkness. Then, they spend another 42 years in constant sunlight. The Sun is almost directly overhead one of the poles during each solstice. When Voyager 2 flew by in 1986, it was summer in Umbriel's southern hemisphere. This meant almost all of the northern hemisphere was dark.

Every 42 years, Uranus reaches an equinox. At this time, its equatorial plane lines up with Earth. This makes it possible for Uranus's moons to pass in front of each other, blocking each other from view. In 2007–2008, scientists saw several such events. For example, Umbriel blocked Titania twice, and it also blocked Ariel.

Umbriel is not currently in a special orbital resonance with any other Uranian moons. In the past, it might have been in a 1:3 resonance with Miranda. This would have made Miranda's orbit more stretched out, which could have heated Miranda's inside and caused geological activity. Umbriel's orbit would not have been affected as much.

What Umbriel is Made Of

Umbriel is the third largest and third heaviest of Uranus's moons. It is also the 13th largest and 13th heaviest moon in our Solar System. Its density is 1.54 grams per cubic centimeter. This tells us that Umbriel is mostly made of water ice. About 40% of its mass is made of something else that is not ice. This non-ice part could be rock and dark, carbon-rich materials.

Scientists have used infrared light to study Umbriel's surface. They found crystalline water ice there. The water ice is more noticeable on the side of Umbriel that faces forward as it orbits (the "leading hemisphere"). Scientists don't know why this is, but it might be because charged particles from Uranus's magnetic field hit the trailing side more. These energetic particles can break down water ice and other materials, leaving behind a dark, carbon-rich layer.

Besides water, the only other material found on Umbriel's surface by infrared studies is carbon dioxide. This gas is mostly found on the trailing hemisphere. Scientists are not completely sure where the carbon dioxide comes from. It might be made on the surface from other materials like carbonates or organic matter. This would happen when energetic charged particles from Uranus's magnetic field or sunlight hit the surface. This idea would explain why there's more carbon dioxide on the trailing side, as that side gets more magnetic field influence. Another idea is that the carbon dioxide came from inside Umbriel long ago, possibly during past geological activity.

Umbriel might have a rocky core in its center, surrounded by an icy mantle. If this is true, the core would be about 317 kilometers (197 miles) wide, which is about 54% of the moon's total radius. The core would also make up about 40% of the moon's total mass. The pressure at Umbriel's center is very high, about 0.24 GPa. Scientists are not sure what the icy mantle is like now, but it's unlikely that there's a liquid ocean under the surface today.

Features on Umbriel's Surface

Umbriel's surface is the darkest of all the moons of Uranus. It reflects less than half the light that Ariel, a similar-sized moon, reflects. Umbriel has a very low Bond albedo of only about 10%. This means it absorbs 90% of the sunlight that hits it. The surface of Umbriel looks slightly blue. However, fresh, bright areas from new impacts (like in the Wunda crater) are even bluer.

There might be a difference in color between Umbriel's leading and trailing sides. The leading side seems to be redder. This reddish color probably comes from "space weathering". This is when charged particles and tiny space dust (micrometeorites) hit the surface over billions of years. However, the color difference on Umbriel might also be caused by reddish material from the outer parts of the Uranian system. This material could collect more on the leading side. Umbriel's surface looks quite the same everywhere. It doesn't show big changes in how bright it is or its color.

Scientists have only officially named one type of geological feature on Umbriel: craters. Umbriel's surface has many more and larger craters than Ariel and Titania. This shows that Umbriel has had the least geological activity. In fact, among the moons of Uranus, only Oberon has more impact craters than Umbriel. The craters seen on Umbriel range from a few kilometers wide up to 210 kilometers (130 miles) for the largest known crater, Wokolo. All the recognized craters on Umbriel have central peaks, but none have bright "rays" of material shooting out from them.

Near Umbriel's equator is its most famous feature: the Wunda crater. It is about 131 kilometers (81 miles) wide. Wunda has a large ring of bright material on its floor. This might be material thrown out by the impact, or it could be pure carbon dioxide ice. This ice might have formed when carbon dioxide from all over Umbriel's surface moved and got trapped in the colder Wunda crater. Nearby, along the line between light and dark (the terminator), are the craters Vuver and Skynd. These don't have bright rims, but they do have bright central peaks. Studies of Umbriel's edge suggest there might be a very large impact feature, about 400 kilometers (250 miles) wide and 5 kilometers (3 miles) deep.

Like other moons of Uranus, Umbriel's surface has a system of canyons that run from northeast to southwest. These are not officially recognized because the images are not clear enough. Also, the moon's generally plain look makes it hard to create a geological map.

Umbriel's heavily cratered surface has probably stayed the same since the Late Heavy Bombardment (a time when many space rocks hit planets and moons). The only signs of old activity inside the moon are the canyons and dark polygons. These polygons are dark patches with complex shapes, from tens to hundreds of kilometers across. They were found by carefully studying Voyager 2's images. They are spread fairly evenly over Umbriel's surface and also run northeast–southwest. Some polygons match depressions that are a few kilometers deep. They might have been created during an early period of tectonic activity (movement of the moon's crust).

Scientists don't currently have a full explanation for why Umbriel is so dark and looks so uniform. Its surface might be covered by a thin layer of dark material. This material could have been dug up by an impact or shot out in a volcanic eruption. Another idea is that Umbriel's entire crust is made of this dark material. This would explain why bright features like crater rays don't form. However, the bright feature inside Wunda crater seems to go against this idea.

| Crater | Coordinates | Diameter (km) | Approved | Named after | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberich | 33°36′S 42°12′E / 33.6°S 42.2°E | 52.0 | 1988 | Alberich (Norse) | WGPSN |

| Fin | 37°24′S 44°18′E / 37.4°S 44.3°E | 43.0 | 1988 | Fin (Danish) | WGPSN |

| Gob | 12°42′S 27°48′E / 12.7°S 27.8°E | 88.0 | 1988 | Gob (Pagan) | WGPSN |

| Kanaloa | 10°48′S 345°42′E / 10.8°S 345.7°E | 86.0 | 1988 | Kanaloa (Polynesian) | WGPSN |

| Malingee | 22°54′S 13°54′E / 22.9°S 13.9°E | 164.0 | 1988 | Malingee (Australian Aboriginal mythology) | WGPSN |

| Minepa | 42°42′S 8°12′E / 42.7°S 8.2°E | 58.0 | 1988 | Minepa (Makua people of Mozambique) | WGPSN |

| Peri | 9°12′S 4°18′E / 9.2°S 4.3°E | 61.0 | 1988 | Peri (Persian) | WGPSN |

| Setibos | 30°48′S 346°18′E / 30.8°S 346.3°E | 50.0 | 1988 | Setebos (Tehuelche) | WGPSN |

| Skynd | 1°48′S 331°42′E / 1.8°S 331.7°E | 72.0 | 1988 | Skynd (Danish) | WGPSN |

| Vuver | 4°42′S 311°36′E / 4.7°S 311.6°E | 98.0 | 1988 | Vuver (Finnish) | WGPSN |

| Wokolo | 30°00′S 1°48′E / 30°S 1.8°E | 208.0 | 1988 | Wokolo (Bambara people of West Africa) | WGPSN |

| Wunda | 7°54′S 273°36′E / 7.9°S 273.6°E | 131.0 | 1988 | Wunda (Australian Aboriginal mythology) | WGPSN |

| Zlyden | 23°18′S 326°12′E / 23.3°S 326.2°E | 44.0 | 1988 | Zlyden (Slavic) | WGPSN |

How Umbriel Formed and Changed

Scientists believe Umbriel formed from a disk of gas and dust that surrounded Uranus. This disk might have been there after Uranus formed, or it could have been created by a huge impact that likely tilted Uranus on its side. The exact makeup of this disk is unknown. However, moons of Uranus are denser than moons of Saturn. This suggests the disk around Uranus had less water. It might have had more nitrogen and carbon in forms like carbon monoxide (CO) and nitrogen gas (N2) instead of ammonia and methane. Moons that formed in such a disk would have less water ice and more rock, which explains their higher density.

Umbriel probably took thousands of years to form. The impacts that happened during its formation heated up the moon's outer layers. The temperature reached about 180 Kelvin (which is very cold, -135 degrees Celsius or -211 degrees Fahrenheit) about 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) deep. After it finished forming, the outer layer cooled down. Meanwhile, the inside of Umbriel heated up because of radioactive elements in its rocks. The cooling outer layer shrank, but the inside expanded. This caused strong pulling forces in the moon's crust, which might have led to cracks. This process likely lasted for about 200 million years. This means any activity inside Umbriel stopped billions of years ago.

The initial heating from its formation, along with the ongoing decay of radioactive elements, might have melted some of the ice. This could happen if there was something like ammonia (in the form of ammonia hydrate) or some salt present to act as an antifreeze. If the ice melted, it could have separated from the rocks. This would lead to a rocky core surrounded by an icy mantle. A layer of liquid water (an ocean) rich in dissolved ammonia might have formed between the core and the mantle. The freezing point of this mixture is 176 Kelvin (-97 degrees Celsius or -143 degrees Fahrenheit). This ocean likely froze solid a long time ago. Among Uranus's moons, Umbriel had the least amount of resurfacing from inside the moon. However, it might have had a very early resurfacing event, just like other Uranian moons.

Exploring Umbriel

The only close-up pictures of Umbriel come from the Voyager 2 probe. This spacecraft took photos of the moon when it flew past Uranus in January 1986. The closest Voyager 2 got to Umbriel was about 325,000 kilometers (202,000 miles). Because of this, the best pictures of Umbriel show details down to about 5.2 kilometers (3.2 miles). The images cover about 40% of Umbriel's surface. However, only 20% of the surface was photographed well enough for scientists to map its features. When Voyager 2 flew by, the southern hemisphere of Umbriel was facing the Sun. This meant the northern (dark) hemisphere could not be studied.

See also

In Spanish: Umbriel para niños

In Spanish: Umbriel para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |