Warsaw Uprising facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Warsaw Uprising |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Operation Tempest, World War II | |||||||

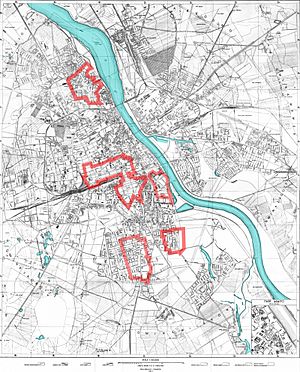

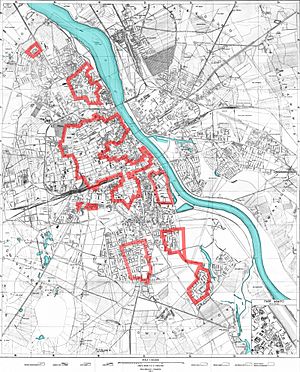

Polish Home Army positions, outlined in red, on day 4 (4 August 1944) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

(18 September only) |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski (POW) Tadeusz Pełczyński (POW) Antoni Chruściel (POW) Karol Ziemski (POW) Edward Pfeiffer (POW) Leopold Okulicki Jan Mazurkiewicz Konstantin Rokossovsky Zygmunt Berling |

Walter Model Nikolaus von Vormann Rainer Stahel Erich von dem Bach Heinz Reinefarth Bronislav Kaminski Petro Dyachenko |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Range 20,000 to 49,000 (initially) | Range 13,000 to 25,000 (initially) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Polish insurgents: 150,000–200,000 civilians killed, 700,000 expelled from the city. |

German forces: 310 tanks and armoured vehicles, 340 trucks and cars, 22 artillery pieces and one aircraft |

||||||

The Warsaw Uprising (Polish: powstanie warszawskie) was a big fight during World War II. It was started by the Polish resistance group called the Home Army. Their goal was to free the city of Warsaw from Nazi Germany.

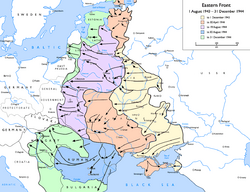

This attack happened as the Soviet Union's Red Army got close to the city from the east. German forces were retreating. But the Soviets stopped their advance. This allowed the Germans to crush the Polish resistance and destroy Warsaw.

The Polish resistance fought for 63 days. They received very little help from other Allied armies. The Uprising was the largest attack ever made by any European resistance group during World War II.

The uprising began on August 1, 1944. It was part of a bigger plan called Operation Tempest. This plan started when the Soviet Army got near Warsaw. The Polish resistance wanted to push the German troops out. They also wanted to free Warsaw before the Soviets arrived. This would help the Polish Underground State take control of the city.

At the start of the battle, the Polish resistance took control of most of central Warsaw. But the Soviets did not move into the city to help them.

By September 14, Polish forces fighting with the Soviets captured the east bank of the Vistula river. The Soviet army still did not help the Poles. They did not even use their military planes to support them.

Winston Churchill asked Joseph Stalin and Franklin D. Roosevelt to help the Polish troops. But the Soviets refused. Churchill sent over 200 air drops of supplies. The US Army Air Force sent one air drop.

About 16,000 Polish resistance fighters were killed. Around 6,000 were badly wounded. Also, between 150,000 and 200,000 Polish civilians were killed. Germans also found Jews who were being hidden by Poles.

The Germans lost over 8,000 soldiers killed or missing. About 9,000 were wounded. During the fighting, about 25% of Warsaw's buildings were destroyed. After the Polish forces gave up, German troops destroyed another 35% of the city.

Contents

Why the Uprising Started

By July 1944, Poland had been under Nazi German control for almost five years. The Polish Home Army was loyal to the Polish government in London. They had planned to attack the Germans. Germany was fighting against a group of Allied powers. These included the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

The Home Army's first plan was to join the Western Allies as they freed Europe from the Nazis. But in 1943, the Soviets were about to reach Poland's pre-war borders. This was happening before the Allied invasion of Europe went very far.

The Soviets and the Poles were both enemies of Nazi Germany. But they had different goals. The Home Army wanted a democratic Poland that was friends with the West. The Soviet leader Stalin wanted to make Poland a communist country. He wanted it to be allied with the Soviet Union.

The Soviets and the Poles did not trust each other. Soviet partisans in Poland often had arguments with Polish resistance troops. These Polish troops were allied to the Home Army.

Stalin stopped all Polish-Soviet relations on April 25, 1943. This happened after the Germans told the world about the Katyn massacre. This was when Polish army officers were killed. Stalin refused to say he ordered the killings.

The Home Army commander, Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski, made a plan on November 20. It was called Operation Tempest. On the Eastern Front, local Home Army units were to attack the German Wehrmacht. They would help Soviet troops.

Before the Battle

On July 13, 1944, the Soviet attack crossed the old Polish border. The Poles had to make a choice. They could attack the Germans, which the Soviets might not support. Or they could do nothing and be criticized by the Soviets.

The Poles worried that if the Red Army freed Poland, the Allies might not accept the Polish government in London after the war.

When the Poles saw what the Soviet forces were doing, they knew they had to decide. In Operation ''Ostra Brama'', Soviet forces shot or arrested Polish officers. They forced lower-ranking soldiers to join the Soviet-controlled Polish forces.

On July 21, the Home Army decided to start Operation Tempest in Warsaw soon. The plan was to show that Poland was its own country. It was also an attack against the German occupiers. On July 25, the Polish government-in-exile approved the plan for an uprising in Warsaw. This was against the views of Polish Commander-in-Chief General Kazimierz Sosnkowski.

In early summer 1944, German plans made Warsaw a key defensive center. The Germans wanted to hold Warsaw no matter how many soldiers they lost. They had built strong defenses and sent many new troops. This slowed down after the failed '20 July plot' to kill Adolf Hitler. The German troops in Warsaw felt weak and unsure.

However, by the end of July, German forces in the area got new troops. On July 27, the German Governor of Warsaw, Ludwig Fischer, ordered 100,000 Polish men and women to build defenses around the city. The people of Warsaw did not follow his order.

The Home Army became worried about possible German revenge or mass arrests. These would make it hard for the Poles to start an attack. Soviet forces were getting closer to Warsaw. Soviet-controlled radio stations told the Polish people to attack the Germans.

On July 25, the Union of Polish Patriots broadcast from Moscow. It told Poles to attack the Germans. On July 29, the first Soviet tanks reached the edges of Warsaw. Two German Panzer Corps, the 39th and 4th SS, attacked them. On July 29, 1944, Radio Station Kosciuszko in Moscow told Poles to "Fight The Germans!".

Bór-Komorowski and other senior officers met that day. Jan Nowak-Jeziorański, who had arrived from London, said Allied support would be weak. On July 31, Polish commanders General Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski and Colonel Antoni Chruściel ordered the Home Army to be ready by 5:00 PM the next day.

Opposing Forces

Polish Fighters

|

Polish Forces Areas

|

The Home Army in Warsaw had between 20,000 and 49,000 soldiers. Other groups also joined. Estimates say about 2,000 to 3,500 came from the National Armed Forces. A few dozen came from the communist People's Army. Most of them had trained for years in guerrilla warfare in cities. But they were not used to fighting in daylight for long periods. The fighters did not have enough weapons. The Home Army had sent weapons to eastern Poland before deciding to include Warsaw in Operation Tempest.

Other resistance groups joined under the Home Army's command. Many volunteers joined during the fighting. This included Jews freed from the Gęsiówka concentration camp in the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto.

Colonel Antoni Chruściel (code name "Monter") led the Polish forces in Warsaw. At first, he divided his forces into eight areas.

On September 20, these areas were changed to match the three parts of the city the Poles held. The whole force was renamed the Warsaw Home Army Corps (Polish: Warszawski Korpus Armii Krajowej). General Antoni Chruściel, who was promoted on September 14, led it. It formed into three infantry divisions: Śródmieście, Żoliborz, and Mokotów.

|

Polish Military Supplies

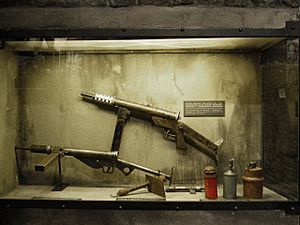

As of August 1, their military supplies included:

|

During the fighting, the Poles got more supplies. They received airdrops and captured weapons from the enemy. This included several armored vehicles, two Panther tanks, and two Sd.Kfz. 251 armored troop carriers. Also, the fighters' workshops made weapons during the fighting. They made submachine guns, K pattern flamethrowers, grenades, mortars, and even an armored car called Kubuś.

German Forces

In late July 1944, German units in and around Warsaw were in three groups. The first was the Warsaw garrison. On July 31, it had 11,000 troops under General Rainer Stahel.

|

German Forces

These forces included:

|

These German forces had good weapons. They had prepared to defend the city for many months. Hundreds of concrete bunkers and barbed wire protected the Germans.

Besides the garrison troops, German army units were on both sides of the Vistula river and in the city. The second group was the police and SS under Colonel Paul Otto Geibel. They started with 5,710 men, including Schutzpolizei (police) and Waffen-SS (military SS). The third group was made of support units. These included the Bahnschutz (rail guard), Werkschutz (factory guard), Sonderdienst, and Sonderabteilungen (Nazi party military units).

During the uprising, the Germans received new troops every day. Stahel was replaced as overall commander by SS-General Erich von dem Bach in early August. By August 20, 1944, the Germans fighting in Warsaw had 17,000 men. They were in two battle groups.

Battle Group Rohr was led by Major General Rohr. It included Bronislav Kaminski's brigade. Battle Group Reinefarth was led by SS-Gruppenführer Heinz Reinefarth. It had Attack Group Dirlewanger (led by Oskar Dirlewanger), Attack Group Reck (led by Major Reck), Attack Group Schmidt (led by Colonel Schmidt), and other support units.

The Uprising Begins

W-hour

At 5:00 PM on July 31, the Polish army decided to start the uprising at 5:00 PM the next day. This decision was a mistake. The Polish forces were not well-equipped. They were only ready for night attacks. Attacking during the day meant many Poles were shot by German machine guns.

Many resistance groups were waiting across the city. But moving thousands of young men and women was hard to hide. Some fighting started before the official attack time. This happened in Żoliborz, and around Napoleon Square and Dąbrowski Square.

The Germans knew the Poles might attack them. However, they did not realize the Poles could launch such a large attack. At 4:30 PM, German troops were told to be ready for an attack.

That evening, the Poles captured a major German weapons building. They also took the main post office and power station, Praga railway station, and the tallest building in Warsaw, the Prudential building. However, Castle Square, the police district, and the airport were still held by the Germans.

The Poles were most successful in the City Centre, Old Town, and Wola districts. But several major German strongholds remained. In some areas of Wola, the Poles had to retreat.

In other areas like Mokotów, the Poles controlled only the residential parts. In Praga, on the east bank of the Vistula, the Poles were forced back into hiding by many German forces.

The Polish groups had trouble contacting other Polish fighting groups. By August 4, Polish forces held most of the city.

First Four Days of Fighting

The uprising was meant to last a few days until Soviet forces arrived. But this never happened. The Polish forces had to fight with little help from outside. The results of the first two days of fighting in different parts of the city were:

- Area I (City Centre and Old Town): Poles captured most of their targets. But they failed to take areas with many Germans. These included the Warsaw University buildings, PAST skyscraper, the German garrison headquarters in the Saxon Palace, the German-only area near Szucha Avenue, and the bridges over the Vistula. They did not capture a central position. They also did not get communication links to other areas. And they did not get a land connection with the northern area of Żoliborz.

- Area II (Żoliborz, Marymont, Bielany): Poles did not capture the most important military targets near Żoliborz. Many troops went back outside the city into the forests. They captured most of the area around Żoliborz. But the soldiers of Colonel Mieczysław Niedzielski ("Żywiciel") did not capture the Citadel area. They also could not break through German defenses at Warsaw Gdańsk railway station.

- Area III (Wola): Units first captured most of the area. But they had heavy losses (up to 30%). Some units went back into the forests. Others went back to the eastern part of the area. In northern Wola, the soldiers of Colonel Jan Mazurkiewicz ("Radosław") captured German barracks. They also took the German supply depot at Stawki Street and the position at the Okopowa Street Jewish Cemetery.

- Area IV (Ochota): The units here did not capture their targets. These included the Gęsiówka concentration camp, and the SS and Sipo barracks on Narutowicz Square. After heavy losses, most Home Army forces went back to the forests west of Warsaw. Only 200 to 300 men under Lieut. Andrzej Chyczewski ("Gustaw") stayed and kept fighting. Troops from the city center were sent to help them. Soldiers of the Kedyw captured most of the northern part of the area and all military targets there. But Germans soon attacked them from the south and west.

- Area V (Mokotów): The fighters tried to capture the Police Area on Rakowiecka Street. They also wanted to connect with the city center. Attacks on these strong positions failed. Some units went back into the forests. Others captured parts of Dolny Mokotów. This area was cut off from most communication with other areas.

- Area VI (Praga): The Uprising also started on the right bank of the Vistula. The goal was to capture the bridges on the river until the Red Army arrived. The forces of Lt.Col. Antoni Żurowski ("Andrzej") were outnumbered by the Germans. The Home Army forces were forced back into hiding.

- Area VII (Powiat warszawski): This area was outside Warsaw city limits. Actions here mostly failed to capture their targets.

The Directorate of Sabotage and Diversion, or Kedyw, was to guard the headquarters. These units secured parts of Śródmieście and Wola. Along with the units of Area I, they were the most successful in the first few hours.

Some important targets were not taken at the start of the uprising. These included the airfields of Okęcie and Mokotów Field. Also, the PAST skyscraper, which overlooked the city center, and the Gdańsk railway station, which guarded the path between the center and northern Żoliborz.

Wola Massacre

On August 4, the Home Army soldiers set up front lines in the westernmost parts of Wola and Ochota. The German army stopped retreating west and began getting new troops. On the same day, SS General Erich von dem Bach was put in charge of all forces fighting the Uprising.

German attacks aimed to link up with other German troops. Then they wanted to block the Uprising troops from the Vistula river. Among the new units were forces led by Heinz Reinefarth.

On August 5, Reinefarth's three attack groups moved west. They went along Wolska and Górczewska streets towards the main East-West Jerusalem Avenue. Their advance was stopped. But the regiments began following Heinrich Himmler's orders to kill civilians. Special SS, police, and Wehrmacht groups went from house to house. They shot people and burned their bodies.

Estimates of civilians killed in Wola and Ochota range from 20,000 to 50,000. Some say 40,000 by August 8 in Wola alone, or as high as 100,000. The main leaders of these killings were Oskar Dirlewanger and Bronislav Kaminski.

Killing civilians was meant to make the Poles stop fighting and end the uprising without heavy city battles. Over time, the Germans realized that killing civilians only made the Poles fight harder.

The Germans started to think about a political solution. This was because their thousands of soldiers could not win against the fighters in city guerrilla warfare.

They wanted a big victory to show the Home Army that fighting more was useless. They wanted the Home Army to give up. This did not work. Until mid-September, the Germans shot all captured fighters. But from late September, some captured Polish soldiers were treated as POWs.

Stalemate in the City

"This is the fiercest [most violent] of our battles since the start of the war. It compares to the street battles of Stalingrad." – SS chief Heinrich Himmler to German generals on 21 September 1944.

Even after losing Wola, the Polish resistance grew stronger. Zośka and Wacek troops captured the Warsaw Ghetto. They also freed the Gęsiówka concentration camp, releasing about 350 Jews.

This area became a key link for communication. It connected fighters in Wola with those defending the Old Town. On August 7, German forces got stronger with the arrival of tanks. The Germans put Polish civilians in front of the tanks. They used them as human shields.

After two days of heavy fighting, they got through Wola and reached Bankowy Square. But by then, the barricades, street defenses, and tank obstacles were well-prepared. Both sides reached a stalemate. This meant neither side could win easily. There was fierce house-to-house fighting.

Between August 9 and 18, violent battles happened around the Old Town and nearby Bankowy Square. Both Germans and Poles made successful attacks. The Germans bombed the Poles with heavy artillery and bombers. The Poles could not defend against the bombers. They did not have anti-aircraft weapons. Even clearly marked hospitals were bombed by Stukas.

The Battle of Stalingrad had already shown how dangerous city fighting was. But the Warsaw Uprising showed that a less-equipped force, supported by civilians, could fight better-equipped professional soldiers.

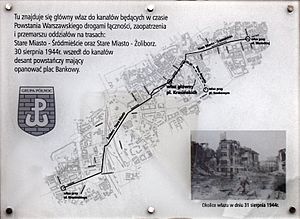

The Poles held the Old Town until they decided to leave at the end of August. Until September 2, the defenders of the Old Town left through the sewers. Thousands of people were moved this way. Those who stayed were either shot or sent to concentration camps like Mauthausen and Sachsenhausen once the Germans took control again.

Berling's Landings

Soviet attacks on the 4th SS Panzer Corps east of Warsaw started again on August 26. The Germans were forced to retreat into Praga. The Soviet army, led by Konstantin Rokossovsky, captured Praga. They arrived on the east bank of the Vistula in mid-September.

By September 13, the Germans had destroyed the remaining bridges over the Vistula. In the Praga area, Polish units fought on the Soviet side. These were led by General Zygmunt Berling. They were sometimes called berlingowcy ("the Berling men"). Three patrols from his First Polish Army (1 Armia Wojska Polskiego) landed in the Czerniaków and Powiśle areas. They joined with Home Army forces on the night of September 14/15.

The artillery and air bombing from the Soviets did not stop enemy machine-gun fire. The Poles had heavy losses as they crossed the river. Only part of the main units made it to shore.

The landings by the 1st Polish Army were the only outside ground forces that came to help the uprising.

The Germans attacked the Home Army positions near the river. They wanted to stop any more landings. But they could not advance for several days. Polish forces held these positions, waiting for Soviet landings.

Polish units from the eastern shore tried more landings. From September 15 to 23, they had heavy losses. This included losing all their landing boats and most river crossing gear. Red Army support was not enough. The 1st Polish Army tried many times to connect with the fighters, but failed. After that, the Soviets only gave occasional artillery and air bombing help.

The same conditions that stopped Germans from defeating the fighters also stopped Poles from defeating Germans. Plans for crossing the river were stopped "for at least 4 months." Fighting against the 9th Army's five panzer divisions was a big problem.

The commander of the 1st Polish Army, General Berling, was removed by his Soviet superiors. On the night of September 19, no more attempts were made from the other side of the river. The evacuation of wounded did not happen that night. Home Army soldiers and the 1st Polish Army left their positions on the river bank.

Out of about 900 men who made it to shore, only a small number got back to the eastern side of the Vistula. Berling's Polish Army lost 5,660 killed, missing, or wounded trying to help the Uprising.

From this point, the Warsaw Uprising became a one-sided war of attrition. Or it was a fight for good surrender terms. The Poles were heavily attacked in three city areas: Śródmieście, Żoliborz, and Mokotów.

Life in the City During the Uprising

In 1939, Warsaw had 1,350,000 people. Over a million were still living in the city when the Uprising began.

In Polish-controlled areas, during the first weeks, people tried to live normally. There were many cultural activities, including theaters and newspapers. Boys and girls from the Polish Scouts delivered mail.

Near the end of the Uprising, life for civilians became very hard. There was little food and medicine. The city was overcrowded. German air and artillery bombing made things worse.

Food and Water Shortages

The Uprising was supposed to be helped by the Soviets in a few days. So, the Polish underground did not think food shortages would be a problem.

But as the fighting continued, people in the city faced hunger. On August 6, Polish units took back the Haberbusch i Schiele brewery. The people of Warsaw then lived on barley from the brewery's storage.

Every day, thousands of people went to the brewery for bags of barley. They then shared it in the city center. The barley was ground in coffee grinders and boiled with water to make a soup. The "Sowiński" Battalion held the brewery until the end of the fighting.

Another big problem for civilians and soldiers was a lack of water. By mid-August, most water pipes were not working. Also, the main water pumping station was held by the Germans.

To stop diseases and give people water, authorities ordered wells to be dug in every backyard. On September 21, the Germans blew up the remaining pumping stations. After that, public wells were the only source of drinking water. By the end of September, the city center had over 90 working wells.

Polish Media During the Uprising

Before the Uprising, the Home Army's Bureau of Information and Propaganda had a group of war journalists. Led by Antoni Bohdziewicz, the group made three newsreels. They also filmed over 30,000 meters of film about the Uprising. The first newsreel was shown to the public on August 13 at the Palladium cinema.

Besides films, dozens of newspapers appeared. Several underground newspapers started to be given out openly. The two main daily newspapers were the government-run Rzeczpospolita Polska and the military Biuletyn Informacyjny. There were also many other newspapers, magazines, and bulletins published by different groups and military units.

The Błyskawica long-range radio transmitter was put together on August 7 in the city center. The military ran it. But the new Polish Radio also used it from August 9.

It broadcast three or four times a day. It shared news programs and asked for help in Polish, English, German, and French. It also broadcast reports from the government, patriotic poems, and music. It was the only resistance radio station in German-held Europe.

Speakers on the radio included Jan Nowak-Jeziorański, Zbigniew Świętochowski, Stefan Sojecki, Jeremi Przybora, and John Ward. Ward was a war reporter for The Times of London.

Lack of Outside Support

Many historians believe the uprising failed because it lacked outside support. Also, the support that did arrive came too late.

The Polish government in London tried to get help from the Western Allies before the battle started. But the Allies would not help without Soviet approval. The Polish government in London asked the British many times to send Allied troops to Poland. However, British troops did not arrive until December 1944. Soon after they arrived, Soviet authorities arrested them.

From August 1943 to July 1944, over 200 British Royal Air Force (RAF) flights dropped supplies. They dropped 146 Polish personnel trained in Great Britain. They also dropped over 4,000 containers of supplies and $16 million in money and gold to the Home Army.

The only support during the Uprising was night supply drops. These were done by long-range planes from the RAF, other British Commonwealth air forces, and units of the Polish Air Force. They had to use airfields in Italy. This reduced how many supplies they could carry.

The RAF made 223 flights and lost 34 aircraft. These air drops mostly gave the fighters hope. But the drops delivered too few supplies for what was needed. Many drops also landed outside the areas controlled by the fighters.

Air Drops

"There was no difficulty in finding Warsaw. It was visible from 100 kilometers away. The city was in flames but with so many huge fires burning, it was almost impossible to pick up [see] the target marker flares." – William Fairly, a South African pilot, from an interview in 1982

From August 4, the Western Allies started helping the Uprising with air drops. They sent ammunition and other supplies. At first, the flights were done by the 1568th Polish Special Duties Flight of the Polish Air Force. This unit was based in Bari and Brindisi in Italy. They flew B-24 Liberator, Handley Page Halifax, and Douglas C-47 Dakota planes.

Later, the Polish government-in-exile asked for more help. So, Liberators from 2 Wing – No.31 and No. 34 Squadrons of the South African Air Force joined. They were based at Foggia in Southern Italy. Halifaxes, flown by No. 148 and No. 178 RAF Squadrons, also joined.

The drops by British, Polish, and South African forces continued until September 21. The total weight of Allied drops varies (104 tons, 230 tons, or 239 tons). Over 200 flights were made.

The Soviet Union did not let the Western Allies use its airports for the air drops. So, the planes had to use bases in the United Kingdom and Italy. This meant they could carry less weight and make fewer flights. The Allies asked to use Soviet landing strips on August 20. But Stalin said no on August 22. Stalin called the fighters "criminals." He said the uprising was started by "enemies of the Soviet Union."

By not giving landing rights to Allied aircraft in Soviet-controlled areas, the Soviets made it hard for the Allies to help the Uprising. The Soviets even shot at Allied airplanes carrying supplies from Italy that entered Soviet airspace.

American support was also limited. After Stalin's objections, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill sent a telegram to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt on August 25. He said they should send planes. Roosevelt did not want to upset Stalin before the Yalta Conference. Roosevelt said he would not send planes.

Finally, on September 18, the Soviets allowed a USAAF flight. It had 107 B-17 Flying Fortress planes from the Eighth Air Force's 3d Air Division. They were allowed to land at Soviet airfields used in Operation Frantic. But it was too late to help the fighters.

The planes dropped 100 tons of supplies. But only 20 tons were picked up by the fighters. This was because the supplies were spread over a wide area. Most of the supplies fell into German-held areas. The USAAF lost two B-17s, and seven more were damaged. The planes landed at the Operation Frantic airbases in the Soviet Union.

The next day, 100 B-17s and 61 P-51s left the USSR. They bombed Szolnok in Hungary on their way back to bases in Italy. The Soviets thought that 96% of the supplies dropped by the Americans fell into German areas.

The Soviets refused permission for any more American flights until September 30. By this time, the weather was too bad to fly. And the uprising was almost over.

Between September 13 and 30, Soviet planes dropped weapons, medicines, and food. At first, these supplies were dropped without parachutes. This damaged and lost the contents. Also, many containers fell into German areas.

The Soviet Air Forces flew 2,535 supply missions with small bi-plane Polikarpov Po-2's. They delivered 156 50-mm mortars, 505 anti-tank rifles, 1,478 sub-machine guns, 520 rifles, 669 carbines, 41,780 hand grenades, 37,216 mortar shells, over 3 million cartridges, 131.2 tons of food, and 515 kg of medicine.

There was almost no German air defense over Warsaw. But about 12% of the 296 planes were lost. This was because they had to fly 1,600 km out and the same distance back over heavily defended enemy territory. (112 out of 637 Polish and 133 out of 735 British and South African airmen were shot down).

Most drops were made at night from 100–300 feet high. Many parachuted packages fell into German-controlled territory. Only about 50 tons of supplies, less than 50% delivered, were found by the fighters.

The Soviet Position

The Red Army's role during the Warsaw Uprising is still debated by historians.

The Uprising started when the Red Army got close to the city. The Poles in Warsaw expected the Soviets to capture the city in a few days.

Starting an uprising against Germans just before Allied forces arrived had worked well in other European capitals. Examples include Paris and Prague.

However, even though the Soviets easily captured the area southeast of Warsaw, they did not help the fighters. Instead, the Soviets waited as the Germans killed the soldiers from the anti-communist Polish Home Army.

At that time, the city edges were defended by the weak German 73rd Infantry Division. The Soviets did not attack these weak German defenses. This allowed the German forces to send more troops to fight the uprising inside the city.

The Red Army was fighting battles south of Warsaw to capture bridges over the Vistula river. They were also fighting north of the city to capture bridges over the Narew river. The best German armored divisions were fighting in those areas.

The Soviet 47th Army did not move into Praga (Warsaw's suburbs) on the right bank of the Vistula until September 11. By then, the uprising was almost over. In three days, the Soviets quickly captured the suburb. The weak German 73rd Division was quickly defeated.

By mid-September, German attacks had shrunk the area held by the Poles. It was just a narrow strip along the riverbank in the Czerniaków district. The Poles hoped Soviet forces would help them.

Berling's communist 1st Polish Army did cross the river. But they did not get much support from the Soviets. The main Soviet force did not follow them.

One reason given for the uprising's failure was that the Soviet Red Army did not help the Resistance. On August 1, the day of the Uprising, the Soviet advance stopped. Soon after, Soviet tanks stopped getting oil.

The Soviets knew about the planned Uprising from their agents in Warsaw. They also knew because Polish Prime Minister Stanisław Mikołajczyk told them about the Polish Home Army's plans. The Red Army's lack of support for the Polish resistance was a decision Stalin made. He wanted the Soviets to control Poland after the war.

If the Polish Home Army had won, the Polish government in London could have returned to Poland. Also, the destruction of the main Polish resistance forces by the Germans helped the Soviet Union. It greatly weakened any possible Polish opposition to Soviet control.

Stopping the advance and then capturing Warsaw in January 1945 allowed the Soviets to say they "freed" Warsaw.

The fact that Soviet tanks were near Wołomin, 15 kilometers east of Warsaw, helped convince Home Army leaders to start the uprising. However, after the battle of Radzymin in late July, these tanks from the Soviet 2nd Tank Army were pushed out of Wołomin and back about 10 km.

On August 9, Stalin told Premier Mikołajczyk that the Soviets had planned to be in Warsaw by August 6. He said an attack by four Panzer divisions had stopped them. By August 10, the Germans had surrounded and badly damaged the Soviet 2nd Tank Army at Wołomin.

When Stalin and Churchill met in October 1944, Stalin told Churchill that the lack of Soviet support was due to Soviet losses in the Vistula area.

Germans thought that the Soviets were trying to help the fighters. The Germans believed their defense of Warsaw stopped the Soviet advance. The Germans did not think that the Soviets did not want to advance.

The Germans published propaganda. It said that both the British and Soviets did not help the Poles.

The Soviet units that reached the edges of Warsaw in late July 1944 had advanced from the 1st Belorussian Front in Western Ukraine. The Soviets defeated many German troops.

The Germans were trying to send new troops to hold the Vistula line. This was the last major river barrier between the Red Army and Germany.

The Germans sent many low-quality infantry units. They also sent 4–5 high-quality Panzer Divisions in the 39th Panzer Corps and 4th SS Panzer Corps.

Other reasons for the Soviet lack of help to the Poles are possible. The Red Army planned a major attack into the Balkans through Romania in mid-August. Many Soviet troops and equipment were sent there. Attacks in Poland were stopped.

Stalin decided to occupy Eastern Europe, rather than moving toward Germany. Capturing Warsaw was not essential for the Soviets. They had already captured bridges south of Warsaw. They were defending them against German attacks.

Finally, the Soviet High Command might not have planned to help Warsaw. This could be because they did not have correct information. Propaganda from the Polish Committee of National Liberation said the Home Army was weak. It also said they were allied with the Nazis. Information given to Stalin by Soviet agents was often wrong.

According to David Glantz, a military historian, the Red Army could not have helped the uprising. This was true regardless of Stalin's political goals. German military strength in August and early September stopped any Soviet help to the Poles in Warsaw. Glantz argued that Warsaw would be a hard city for the Soviets to capture from the Germans. Also, Warsaw was not a good place for future Red Army attacks.

Aftermath of the Uprising

Surrender

"The 9th Army has crushed the final resistance in the southern Vistula circle. The insurgents fought to the very last bullet." – German report, September 23 (T 4924/44)

By the first week of September, both German and Polish commanders knew the Soviet army would not attack and break the stalemate. The Germans thought a longer uprising would make it hard to hold Warsaw as the frontline. The Poles worried that continued fighting would lead to many deaths. On September 7, General Rohr suggested talking. Bór-Komorowski agreed to discuss it the next day.

Between September 8, 9, and 10, about 20,000 civilians were allowed to leave the city. Rohr said Home Army fighters had the right to be treated as soldiers. The Poles stopped talks on the 11th. They heard news that the Soviets were moving through Praga. A few days later, the arrival of the 1st Polish Army gave the resistance confidence. The talks stopped.

However, by the morning of September 27, the Germans had recaptured Mokotów. Talks started again on September 28. On the evening of September 30, Żoliborz was captured by the Germans. The Poles were being pushed into a smaller area and were at risk of being killed. On the 30th, Hitler gave awards to von dem Bach, Dirlewanger, and Reinefarth. In London, General Sosnkowski was removed as Polish commander-in-chief. Bór-Komorowski was promoted to commander-in-chief, even though he was trapped in Warsaw.

Bór-Komorowski and Prime Minister Mikołajczyk again asked Rokossovsky and Stalin for Soviet help. None came. According to Soviet Marshal Georgy Zhukov, who was at the Vistula front, both he and Rokossovsky advised Stalin against an attack. This was because of heavy Soviet losses.

The order for the remaining Polish forces to surrender was signed on October 2. All fighting stopped that evening. According to the agreement, the Wehrmacht promised to treat Home Army soldiers by the Geneva Convention. They also promised to treat civilians humanely.

The next day, the Germans began to disarm the Home Army soldiers. They later sent 15,000 of them to POW camps in Germany. Between 5,000 and 6,000 fighters decided to blend in with the civilians. They hoped to continue fighting later. All civilians in Warsaw were removed from the city. They were sent to camp Durchgangslager 121 in Pruszków.

Out of 350,000–550,000 civilians who went through the camp, 90,000 were sent to labor camps in the Third Reich. 60,000 were sent to death and concentration camps. These included Ravensbrück, Auschwitz, and Mauthausen. The rest were sent to different places in the General Government and released.

The Eastern Front did not change in the Vistula area. The Soviets did not try to push forward. This was until the Vistula–Oder Offensive began on January 12, 1945. Warsaw was almost completely destroyed. It was freed from the Germans on January 17, 1945, by the Red Army and the First Polish Army.

Destruction of Warsaw

"The city must completely disappear from the surface of the earth...No stone can remain standing. Every building must be [destroyed]..." – SS chief Heinrich Himmler, October 17, SS officers conference

The destruction of the Polish capital was planned before World War II began. Warsaw was meant to become a small German city. The failure of the Warsaw Uprising gave Hitler a chance to start this change.

After the remaining people were removed, the Germans continued to destroy the city. German engineers burned and tore down the remaining buildings. According to German plans, after the war, Warsaw was to become a military station. Or even an artificial lake. The Nazi leaders had already planned this for Moscow in 1941. The demolition teams used flamethrowers and explosives to destroy houses. They destroyed historical monuments, Polish national archives, and important places.

By January 1945, 85% of the buildings were destroyed. 25% was due to the Uprising. 35% was due to German actions after the uprising. The rest was from the earlier Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the September 1939 campaign. The total material losses are unknown but are thought to be huge. Studies in the late 1940s estimated total damage at about US $30 billion.

In 2004, President of Warsaw Lech Kaczyński, who later became President of Poland, set up a group to estimate the losses caused by German authorities. This group estimated the losses at least US $31.5 billion in 2004 values. These estimates were later raised to US $45 billion in 2004 dollars. In 2005, they went up to $54.6 billion.

Casualties of the Uprising

The exact number of people killed or injured on both sides is not known. Estimates for deaths are generally similar. Polish civilian deaths are thought to be between 150,000 and 200,000. Both Polish and German military losses are estimated at under 20,000 each.

| Side | Civilians | KIA | WIA | MIA | POW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polish | 150,000–200,000 | 15,200 16,000 16,200 |

5,000 6,000 25,000 |

all declared dead | 15,000 |

| German | unknown | 7,000 to 9,000 killed, or 16,000 killed and missing | 9,000 | 7,000 | 2,000 to 5,000 |

In addition, Germans lost valuable military equipment. This included three aircraft, 310 tanks and armored cars, 340 trucks and cars, and 22 light (75 mm) artillery pieces.

After the War

Most Home Army soldiers, including those in the Warsaw Uprising, were captured by the NKVD (Soviet secret police) or UB (Polish political police). They were questioned and put in prison for things like "fascism."

Many were sent to Gulags (Soviet labor camps) or killed. Between 1944 and 1956, all former members of Battalion Zośka were put in Soviet prisons. In March 1945, a staged trial of 16 leaders of the Polish Underground State happened in Moscow. This was called the Trial of the Sixteen.

The Government Delegate and most members of the Council of National Unity were invited to a meeting. The Commander-in-Chief of the Armia Krajowa was also invited. Soviet general Ivan Serov, with Stalin's agreement, invited them to talk about joining the Soviet-backed Provisional Government.

They were promised safety. But they were arrested in Pruszków by the NKVD on March 27 and 28. Leopold Okulicki, Jan Stanisław Jankowski, and Kazimierz Pużak were arrested on the 27th. Twelve more were arrested the next day. A. Zwierzynski had been arrested earlier.

They were taken to Moscow, to the Lubyanka prison.

After months of harsh questioning and torture, they were accused of "collaboration with Nazi Germany" and "planning a military alliance with Nazi Germany." These accusations were false.

Many fighters captured by the Germans were sent to POW camps in Germany. They were later freed by British, American, and Polish forces. Many stayed in the West. Among them were the uprising leaders: Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski and Antoni Chruściel.

The facts of the Warsaw Uprising were a problem for Stalin. The facts were changed in the propaganda of the People's Republic of Poland. This propaganda highlighted the failures of the Home Army and the Polish government-in-exile. It did not allow criticism of the Red Army or the Soviet Union's goals.

After the war, the Home Army's name was banned. Most films and books about the 1944 Uprising were banned or changed. The Home Army's name could not appear. From the 1950s, Polish propaganda showed the uprising soldiers as brave. But it showed the officers as traitors and uncaring about losses.

The first serious books about the topic in the West were not published until the late 1980s. In Warsaw, no monument to the Home Army was built until 1989. Instead, the efforts of the Soviet-backed People's Army were praised and made to seem bigger.

In contrast, in the West, the story of the Polish fight for Warsaw was told as brave heroes fighting a cruel enemy. It was suggested that Stalin benefited from the Soviet failure to help. The opposition to Soviet control of Poland was removed when the Nazis killed the fighters.

The belief that the Uprising failed because of the Soviet Union added to anti-Soviet feelings in Poland. Memories of the Uprising helped inspire the Polish labor movement Solidarity. This group led a peaceful opposition movement against the Communist government in the 1980s.

Until the 1990s, there was little historical study of the events. This was due to official censorship and a lack of academic interest. Research into the Warsaw Uprising grew after the fall of communism in 1989. This happened because censorship ended and state archives became more accessible. However, as of 2004, access to some material in British, Polish, and former Soviet archives was still limited.

It is also complicated by the British claim that the records of the Polish government-in-exile were destroyed. Material not given to British authorities after the war was burned by the Poles in London in July 1945.

In Poland, August 1 is now a special anniversary. On August 1, 1994, Poland held a ceremony for the 50th anniversary of the Uprising. Both the German and Russian presidents were invited. The German President Roman Herzog attended. But the Russian President Boris Yeltsin declined. Other important guests included U.S. Vice President Al Gore.

Herzog, on behalf of Germany, was the first German leader to apologize for German cruelties against the Polish nation during the Uprising. During the 60th anniversary in 2004, official groups included German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, UK Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott, and US Secretary of State Colin Powell. Pope John Paul II sent a letter to the mayor of Warsaw, Lech Kaczyński. Russia again did not send a representative. A day before, on July 31, 2004, the Warsaw Uprising Museum opened in Warsaw.

Images for kids

-

Commander Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski of the Polish Home Army.

-

Captured German Sd.Kfz. 251 from the 5th SS Panzer Division Wiking, and pressed into service with the 8th "Krybar" Regiment. The soldier holding a MP 40 submachine gun is commander Adam Dewicz "Gray Wolf", August 14, 1944.

-

Picture of the Uprising taken from the opposite side of the Vistula river. Kierbedź Bridge viewed from Praga District towards Royal Castle and the Old Town, 1944.

-

German SS-Gruppenführer Heinz Reinefarth nicknamed the "Butcher of Wola" (left, in Cossack headgear) alongside Jakub Bondarenko the commander of the 3rd Regiment of Kuban Cossack Infantry, pictured during the Warsaw Uprising, 1944.

See Also

In Spanish: Alzamiento de Varsovia para niños

In Spanish: Alzamiento de Varsovia para niños