A. J. Mundella facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

A. J. Mundella

|

|

|---|---|

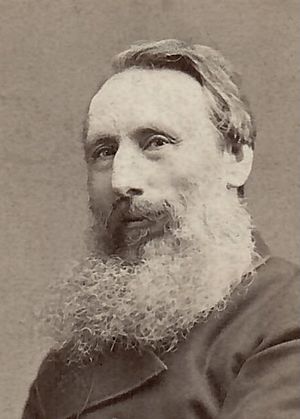

Mundella, c1885

|

|

| President of the Board of Trade | |

| In office 17 February 1886 – 20 July 1886 |

|

| Monarch | Queen Victoria |

| Prime Minister | William Ewart Gladstone |

| Preceded by | Hon. Edward Stanhope |

| Succeeded by | Hon. Frederick Stanley |

| In office 18 August 1892 – 28 May 1894 |

|

| Monarch | Queen Victoria |

| Prime Minister | William Ewart Gladstone The Earl of Rosebery |

| Preceded by | Sir Michael Hicks Beach, Bt |

| Succeeded by | James Bryce |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 28 March 1825 Leicester, Leicestershire |

| Died | 21 July 1897 (aged 72) London |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse | Mary Smith |

Anthony John Mundella (born March 28, 1825 – died July 21, 1897) was an important English businessman. He later became a Liberal Party Member of Parliament (MP) and a Cabinet Minister. He served in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom from 1868 to 1897.

Mundella worked under Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone. He was the Vice-President of the Committee of the Council on Education from 1880 to 1885. He also served as President of the Board of Trade in 1886 and again from 1892 to 1894.

As Education Minister, he helped make sure all children in Britain had to go to school. He played a big part in building the state education system. At the Board of Trade, he helped reduce working hours and raised the minimum age for children and young people to work. He was also one of the first to show that talking things out (called arbitration and conciliation) could solve problems between workers and bosses. He also introduced the first laws to protect children from harm. His work in the late Victorian period helped shape society in the 20th century.

Contents

Early Life and Beginnings

Anthony John Mundella was born in Leicester, England, in 1825. He was the first of five children. His father, Antonio Mondelli (later Anthony Mundella), was a refugee from Italy. His mother, Rebecca Allsopp, was from Leicester.

When Mundella was born, his father worked in the hosiery (sock and stocking) trade and earned very little. His mother made lace at home, but she also earned poorly. After paying for rent and for her lace-making frame, there was often not much money left for the family.

Mundella went to the Church of England school of St Nicholas in Leicester until he was nine. This school helped provide basic education for poor children. He didn't like some of the religious lessons, but he remained loyal to his early education. His mother, who loved English literature, especially Shakespeare, taught him to appreciate nature, books, and art.

Because his mother's eyesight got worse, she couldn't make lace anymore. So, young Anthony had to leave school to help the family earn money. At nine, he started working in a printing office. This job helped him learn even more. At eleven, he became an apprentice to William Kempson, who made footwear and hosiery.

From his father and other Italian visitors, Mundella learned about politics from a young age. At fifteen, he became interested in politics and joined the Chartist movement. He wrote political songs that were sung in the streets. He even gave his first political speech at fifteen, supporting the Charter, which asked for more rights for working people. He was also inspired by Richard Cobden, who campaigned to repeal the Corn Laws, which made bread expensive. Mundella always supported the causes of working-class people.

Mundella regularly attended Sunday School. As he grew older, he became a teacher, then a secretary, and finally the leader of a large Sunday School in Leicester.

At eighteen, Mundella left Kempson's. He became a journeyman (a skilled worker), then an overseer, and finally a manager at Harris & Hamel, another hosiery company in Leicester. He earned good money and married at eighteen. He worked there for three years. During this time, the company secretly experimented with steam-powered machines. Mundella wasn't a technical expert, but this experience made him very interested in new steam-powered hosiery machines. He believed steam power could help workers escape poverty.

Building a Business

In 1848, Mundella was offered a partnership with Hine & Co, an old hosiery company in Nottingham. They needed help building a new factory. He became a partner, and the company soon became Hine & Mundella.

For the next fifteen years, Mundella worked hard to improve the hosiery industry. Before, most stockings were made on old machines by poor workers in their homes. Mundella introduced many changes, including new machines that made tubular knitting. He encouraged inventors within the company, sharing patents with them. This led to new steam-powered machines, including one that could make a stocking automatically without stopping. This made stockings a hundred times faster than before.

In 1851, Mundella built a large new factory in Nottingham. It was the first steam-operated hosiery factory in the city. It had bright, spacious workrooms and the best machines. By 1857, Hine and Mundella employed 4,000 workers who were paid well. Mundella believed that good conditions made workers more loyal and encouraged them to suggest improvements.

In 1859, the factory was damaged by fire, but it was quickly rebuilt with even newer and more powerful machines. Hine and Mundella continued to grow. They opened factories in Loughborough in 1859 and Chemnitz, Saxony in 1866. They also got a warehouse in London.

In 1860, strikes and lock-outs affected Nottingham's hosiery business. Workers wanted higher pay. Mundella organized a meeting between workers and employers. He suggested that workers should get the wages they asked for. He also proposed a Board of Arbitration (the Nottingham Board of Arbitration and Conciliation for the Hosiery Trade). This board, made of both employers and workers, would prevent future strikes by agreeing on prices for handwork and solving disputes through talks. Mundella showed that preventing problems was better than fixing them later.

This idea of talking things out (conciliation) was not completely new, but Mundella was the first to show it worked in a complex industry like hosiery. It was a big success and was adopted in other parts of Britain, continental Europe, and the United States.

In 1863, Mundella's health suffered from the stress of business. He went to Italy to recover for two years. While he was away, Hine & Mundella became a limited liability company, the Nottingham Hosiery Manufacturing Company. The company kept growing, with interests in Saxony and Boston, USA.

Mundella made the business very successful. When he joined Hine & Co in 1848, it made £18,000 a year. When he left in 1873, it made £500,000 a year. He left because it was hard to manage the business in Nottingham while being an MP in London.

Mundella was a well-known public figure in Nottingham. He was active in the local Liberal Party and became Sheriff of Nottingham in 1852 at age 28. In 1856, he was elected a town councillor and helped start the Nottingham Chamber of Commerce. He also helped create the local volunteer army group, the Robin Hood Rifles, in 1859.

Mundella's business experience taught him that industry needed good understanding between workers and bosses. He also believed that progress needed better education, including technical training. He knew that very young children couldn't learn properly if they were working in factories. When he traveled in Europe, he saw that other countries, like Switzerland and Germany, had much better education systems than England. He realized that improving these things would require teamwork and more government help. His own working past also convinced him that trade unions were necessary. In 1868, he got the chance to put his beliefs into action.

Entering Politics

After Mundella successfully helped solve the Nottingham industrial problems in 1863, many towns asked him to explain his arbitration system and help with their own labor conflicts. Violence in the Sheffield steel industry led to a Royal Commission on Trade Unions in 1867. Mundella showed the Commission that unions could be helpful and that working men could be trusted.

In 1868, he spoke at a meeting in Sheffield. The people there were so impressed that they promised to support him if he ran for the Liberal Party in Sheffield in the upcoming General Election.

Mundella had already said he didn't want to keep working just to get rich. He wanted to focus on political life. He agreed to run and was officially chosen as a Liberal candidate on July 20, 1868.

The election in Sheffield was very tough. Mundella faced many attacks. People made fun of his Italian background and his looks. His business ethics were questioned. But thanks to the Reform Act of 1867, which allowed many more men to vote, Mundella won in Sheffield. He represented Sheffield, and later Sheffield Brightside, until he died almost thirty years later.

A Political Career Begins

Mundella took his seat in the House of Commons. The Liberal Party had a large majority. He was seen as confident, respected for his work in industrial arbitration, and an expert on social issues. People quickly saw him as a hard worker and one of the most highly regarded new MPs.

Mundella was chosen to give a speech on February 16, 1869, which was his first speech in Parliament. The Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone, praised his speech. In March, Mundella's reputation grew even more when his Board of Arbitration was praised in a new report from the Royal Commission on Trade Unions.

Working for Change

When Mundella first joined Parliament, his main goals were to reform trade unions and to make schooling free and compulsory, along with technical training. He strongly believed in the right of working men and women to form unions to protect their interests. Much of his energy in Parliament was spent trying to give them the same rights as their employers.

In 1869, Mundella started planning a bill to make unions legal and protect their money. Even though his bill didn't pass on its own, his efforts led to a temporary government bill that protected union funds. Two years later, this led to the Trade Union Act 1871, which made trade unions legal and protected their money.

Mundella also strongly supported the Elementary Education Act 1870. His speech on this bill greatly improved his reputation in Parliament. While this Act created local education authorities and provided public money for schools, it didn't make schooling free or compulsory everywhere. However, Mundella wanted to accept what Parliament offered rather than reject it completely.

Besides unions and education, Mundella worked on other issues. He criticized the War Office for its old-fashioned system for army contracts. He supported shorter army and navy service and better organization. He also tried to update Patent Laws, which he cared about as a businessman. He spoke against the "absurdity" of complicated postal rates and criticized old game laws that sent many people to jail for poaching.

Mundella was also very concerned about very young children working. He knew that their work made it impossible for them to get a proper education. In 1871, he proposed a measure to control child labor in brick and tile factories. His idea was so popular that it was added to the government's Factory and Workshop Act of 1871. This law stopped girls under sixteen and boys under ten from working in brick and tile yards.

In 1872, Mundella's long interest in arbitration led to his Arbitration (Masters and Workmen) Act, often called Mundella's Act. This law made voluntary agreements between bosses and workers legally binding. In the same year, he helped pass the Coal Mines Regulation Act, focusing on rules that limited working hours for women and children. He continued to campaign for fewer hours for women and children with a Nine-Hours Factory Bill in 1872, but it faced opposition and was withdrawn in 1873.

Mundella's constant concern for children also led him to introduce a bill in 1873 to protect children from people who had been found guilty of harming them.

Working from Opposition

In the 1874 General Election, the Liberal Party lost power. But Mundella continued his work from the opposition benches. He reintroduced his Nine-Hours Bill. The Conservative government then introduced their own Factory Bill, which aimed for similar goals. The Factories (Health of Women, &c.) Act of 1875 set a ten-hour workday for women and children in textile factories. Many people in textile areas recognized that Mundella's efforts had made this law possible.

Trade union leaders also praised Mundella. He helped change and pass two important laws in 1875: the Employers and Workmen Bill, which replaced the harsh Masters and Servants Acts, and the Conspiracy, and Protection of Property Bill. These laws, along with repealing the disliked Criminal Law Amendment Act 1871, removed severe punishments for workers. Together, these acts made the work of trade unions legal and protected.

Mundella also helped pass a law in 1878 that created a closed season for freshwater fish from March 15 to June 15. This law, officially called the Freshwater Fisheries Act, was known by anglers as the Mundella Act.

In 1877, Mundella tried to pass a bill to remove the property requirement for holding local office. He pointed out that many voters in his area couldn't become councillors because they didn't own enough property. This bill didn't pass at first, but the Conservatives finally passed a similar measure in 1880.

Leading Education Reform

The Liberals returned to power in 1880. Prime Minister Gladstone recognized Mundella's knowledge in education reform and appointed him Vice-President of the Committee of the Council on Education. This meant he was in charge of education. Mundella was also made a Privy Councillor.

Queen Victoria initially described him as "one of the most violent radicals." But Gladstone praised him, saying he was religious and supported religious education. Mundella was also appointed as a Charity Commissioner.

Even though he was junior to another minister, Mundella was in charge of Education. He could now achieve his goals, especially making elementary education compulsory. He worked hard, despite strong opposition. The Times newspaper said that compulsory education might work for other countries but not for the English. Mundella replied that it was "peculiarly English to be content to be in ignorance."

Soon after taking office, Mundella introduced a bill to make school attendance compulsory, which previous laws hadn't fully achieved. The Mundella Act, officially the Elementary Education Act 1880, became law just four months after the Liberals returned to power. It made sure all children would be sent to school.

Mundella then started reorganizing technical education. He had always been interested in higher education, technical training, and art schools. As his first step in higher education, Mundella combined scientific schools in South Kensington, London, creating the Normal School of Science and Royal School of Mines in October 1881.

Mundella also set up a committee to study and recommend improvements for higher education in Wales. The committee suggested expanding Welsh intermediate schools and creating university colleges in Cardiff and Bangor. Mundella also started a Royal Commission to compare technical education in England with that in other countries.

Mundella was also responsible for developing the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum). As an art lover, he enjoyed this part of his job.

Mundella's education rules of 1882, known as the "Mundella Code," changed how public elementary schools were run. It set new rules for their lessons, teaching methods, and how government money was given out. By 1883, funds were available to make the code work. Mundella improved school inspections, including hiring some women inspectors. He insisted that children's health and mental abilities should be considered when checking their progress. He also improved teacher training.

Some people said the code was too strict and made children overwork. But the medical journal The Lancet said that the problem wasn't overworking, but that children were underfed. This made Mundella urge local governments to provide cheap meals for children.

Mundella also introduced bills to improve Scottish education and extend compulsory elementary education to Scotland.

In May 1885, Mundella began to introduce a measure to promote intermediate education in Wales. However, on June 9, 1885, Gladstone resigned, and Mundella had to leave his position. His Welsh law did not pass.

Back in the Cabinet

In the General Election of October 1885, Mundella won his seat in the new constituency of Brightside. Nationally, the election was close, and the Conservatives took office. Mundella remained on the Liberal frontbench (a leading position in the opposition).

Gladstone became Prime Minister again in January 1886. After thinking about making Mundella Chancellor of the Exchequer (in charge of the country's money), he instead made him a Cabinet Minister as President of the Board of Trade.

First Term as President of the Board of Trade

Mundella had little time to make big new laws before the next election, but he made several administrative changes.

He made sure that reports from consuls about trade and the needs of different countries were published and available cheaply. Before, these reports were often hidden among other government papers. He also created a labor statistics bureau to share information with the working class. He expanded the Board of Trade to include a fisheries department, which had previously been handled by three different government departments. This new department looked after both sea and inland fisheries.

There had been long arguments about railway freight charges. Businesses and farmers were unhappy with the high prices for moving goods. To fix this, Mundella introduced his Railway and Canal Traffic Bill. This bill would give the Board of Trade control over railways, including the power to force companies to lower their charges. Mundella faced strong opposition from railway companies and their shareholders, who feared losing up to 50 percent of their profits.

They were also angry about Mundella's Railway Regulation Bill, which aimed to make railways safer with better brakes. Opposition to the Railway and Canal Traffic Bill grew alongside strong opposition to Irish Home Rule. Gladstone's government fell over the Irish issue, and Mundella's railway reforms failed.

Working from Opposition Again

Mundella's short time as head of the Board of Trade ended on July 30, 1886. In the August General Election, the Conservatives won power again. From the Opposition frontbench, Mundella continued to campaign for more technical education for working people. He helped start the National Association for the Promotion of Technical Education. This group became important in developing education, including secondary and technical education. Mundella also led the new National Education Association, which promoted a "free progressive system of national education, publicly controlled and free from sectarian interest."

In 1888, Mundella introduced a bill to prevent cruelty to children. Progress was slow due to opposition, and Mundella spoke 65 times in committee meetings about it. The resulting Prevention of Cruelty to, and Protection of, Children Act 1889 (often called the Children's Charter) was the first law in Parliament to outlaw cruelty to children. It allowed the state to step in between parents and children, made it a crime to neglect or harm children, and made it illegal to employ children under the age of 10. Mundella considered this Act one of his greatest successes.

In 1890, Mundella became chairman of the Trade and Treaties Committee. This committee kept the Board of Trade informed about expiring trade agreements and new taxes on goods. In 1891 and 1892, at Gladstone's request, he became an Opposition representative on the Royal Commission on Labour. He led the part of the commission that looked at conditions in chemical, building, textile, clothing, and other trades. He was able to arrange for four women inspectors to examine the situation of women in industry.

Second Term as President of the Board of Trade

In the 1892 General Election, Mundella won his seat in Sheffield Brightside with an even larger majority. The Liberal Party formed the government, and Mundella returned to the Cabinet and to the Presidency of the Board of Trade.

There, Mundella again faced the railway companies. Farmers and businesses still wanted lower freight charges. To avoid angering the railway companies too much, Mundella set up a committee in 1893 to look into the charges. He also helped pass the Railway Servants (Hours of Labour) Act, which allowed railway employees to reduce their working hours.

In early 1893, the Bureau of Labour Statistics, which Mundella had set up in his first term, was expanded into a separate Labour department. This department published a regular Labour Gazette to share information about labor with working-class people.

In 1893, there was a lock-out of miners in the Midlands. Nearly 320,000 men were out of work because they refused a pay cut. Mundella encouraged talks, and the coal strike was settled. This conflict led Mundella to introduce a bill to create local boards for conciliation and arbitration whenever needed.

Mundella also helped with three maritime reforms. The North Sea Fisheries Act created an agreement between countries bordering the North Sea fishing areas to deal with floating alcohol "shops" that supplied liquor to fishermen. A Merchant Shipping Bill was introduced to stop ships from being understaffed.

Concerned by the annual reports of railway accidents and deaths, Mundella appointed two railway experts to investigate the accidents and find ways to improve safety.

Mundella was highly respected at this time. In early 1894, Gladstone wrote that Mundella "has done himself much credit in the present government."

Resignation and Later Years

In 1869, Mundella had joined the board of the New Zealand Loan and Mercantile Agency Company. It was a successful business, and Mundella made money from it. When he became President of the Board of Trade in 1892, he had to give up all his directorships, so he no longer controlled the company's activities.

In 1893, due to an economic downturn, the company went out of business and was investigated by the Board of Trade. Even though Mundella was no longer a director and had done nothing wrong, there was a conflict of interest. The final decision on what should happen after a public investigation (where Mundella gave evidence) would have to be made by Mundella himself as President of the Board of Trade. He was in a difficult position, and his role as President became impossible.

Mundella offered his resignation to Lord Rosebery, who was then Prime Minister. Rosebery asked him to stay, but Mundella insisted, and his resignation took effect on May 12, 1894. On May 24, he spoke to the House of Commons about the matter. The magazine Punch wrote that "The House felt that here was a good man suffering with adversity... Mundella behaved with dignity that earned the respect of the House."

Mundella wrote to his sister: "I was received with loud cheering when I entered the House... Men crowded round me all night to shake hands with me." Gladstone and Rosebery praised him, and hundreds of messages of support came from workers across the country, thanking him for his lifelong service to labor. He did not return to a ministerial position but served as a regular MP until the 1895 General Election.

In the year after his resignation, Mundella successfully helped resolve the Hanley Pottery dispute in March 1895. He also worked hard as Chairman of a committee examining the poor law schools in London.

The General Election of July 1895 saw the Conservatives win. The Liberal Party was back in Opposition. Mundella was re-elected without opposition for Sheffield Brightside. His colleagues in the House asked him to return to the Opposition frontbench. From that position, despite his age, he continued to fight for his favorite causes. He strongly opposed the Education Bills of 1896 and 1897, which he felt would harm his education policies. He complained that the compulsory parts of his Education Act were not being enforced, leading to many children not attending school and widespread illiteracy.

Mundella's last words in the House of Commons, after nearly thirty years as an MP, were a brief comment during a debate on the Education (Scotland) Bill on July 1, 1897.

Death and Legacy

Mundella died unexpectedly. On July 14, 1897, his butler found him unconscious in his bedroom. He had suffered a stroke and remained paralyzed and barely conscious for eight days. Many people, including Queen Victoria, expressed concern. He died at 1:55 pm on July 21, 1897, at the age of 72.

Three funeral services were held. The first was at St Margaret's, Westminster on July 26. Queen Victoria sent a wreath, and many important people attended. It was noted that an unusually large number of working men came to pay their respects.

Mundella's coffin was then taken by train to Nottingham. A second funeral service was held in Nottingham at St Mary's Church on July 27. It was the largest funeral the city had ever seen. Crowds lined the route to the Church Cemetery, where a third service was held at the graveside. He was buried in the Mundella vault with his parents, wife, and youngest brother.

A large stone with classical and Arts and Crafts designs was placed over the tomb. It reads: "Loving knowledge for its own sake, he strove to diffuse it among his countrymen. He laboured for industrial peace, and the welfare of the children of the poor."

Mundella was highly respected during his long time in Victorian politics. He became a Cabinet Minister and was known as a Statesman. Some say he had "the most productive mind in late Victorian England" when it came to education, industry, and labor. His political achievements in these areas were remarkable.

His work helped prepare the late Victorian age for the 20th century. Many of the improvements he supported have changed over time, but their long-term effects are still with us today. Children still have to go to school, trade unions are still legal, and freshwater fish still have a peaceful breeding season.

Despite his powerful influence, Mundella's reputation faded quickly after his death in 1897. For 55 years, he was mostly forgotten. One reason might be that an early biography was never published. His daughter, Maria Theresa, worked on a biography but died in 1922 before finishing it. Her papers were later given to the University of Sheffield Library.

A biography finally appeared in 1951 by Harry Armytage. Mundella is often mentioned in books about the Victorian hosiery business, the history of education, and early labor relations. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography rewrote his entry in 2004.

However, these efforts haven't fully brought Mundella's reputation back into the spotlight. He is not in the Encyclopaedia Britannica. There is no public monument to him. Mundella Grammar School in Nottingham no longer exists. A request for a blue plaque at his London home was refused. His portrait by Cope is not on public display. The National Portrait Gallery in London has not shown his likenesses in public.

Mundella's important contributions to British society, education, labor relations, trade unions, and child protection remain mostly, but not completely, forgotten.

Personal Life

On March 12, 1844, at age eighteen, Mundella married Mary Smith, the daughter of a warehouseman from Kibworth Beauchamp in Leicestershire. They had two daughters, Eliza Ellen and Maria Theresa.

When Mundella was a manufacturer, he had a large new house built in The Park Estate in Nottingham. After moving to London when he became an MP, they lived in Dean's Yard in Westminster, then rented a house in Stanhope Gardens in Kensington. In late 1872, they bought 16 Elvaston Place nearby.

While he had made money in business, Mundella was never extremely rich. The collapse of the New Zealand company, which caused his resignation, left him with financial problems. However, on Lord Rosebery's recommendation, he was given an annual Civil List pension of £1,200. This allowed him to continue living in Elvaston Place.

Mundella had a striking appearance. He was tall, thin, and slightly bent at the shoulders, with a dark complexion, a prominent hooked nose, and a long beard. He was easily recognizable in London. People described him as warm, enthusiastic, and optimistic.

It has been said that "Mundella made enemies at every stage." He was very confident and strong-willed. As he got older, the Cabinet respected him, but younger politicians were sometimes annoyed by his constant focus on a few main topics.

At home, Mundella enjoyed comfort and liked to be surrounded by beautiful things. One of his nieces remembered that his family thrived when Italian things were popular, and having Italian ancestry was seen as desirable. Their house at 16 Elvaston Place was full of beautiful Italian items. The house was often filled with friends, including politicians, artists, writers, business people, and journalists.

Mundella became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1882, an honor he deeply valued. In 1884, he became President of the Sunday School Union, a position he cherished. His rise in politics brought him from his working-class background into the world of the rich, the aristocratic, and even royalty. After her initial doubts, Queen Victoria grew to care for him and invited him to her homes. She was saddened by his death.

Even though Mundella was not Jewish (his mother was a Protestant and his father a Catholic), his looks, foreign-sounding name, and unique style sometimes led opponents and hostile journalists to use anti-semitic insults against him.

Despite Mundella's claim in 1894 that he had "insufficient private means," his estate was valued at £42,619 when he died three years later.

Mundella's Portraits and Images

- Oil Portrait: By Sir Arthur Stockdale Cope RA (1857–1940). This painting was commissioned by the people of Sheffield to celebrate Mundella's 25th anniversary as an MP. It shows Mundella as President of the Board of Trade. The Sheffield Telegraph noted that "His face wears a somewhat sad and serious expression." The painting was shown at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1894 and then given to Sheffield Town Council. It is now on loan to Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust.

- Replica Portrait: A copy of the above portrait, also by Cope, was given to Mundella's daughter, Maria Theresa. Its current location is unknown.

- Oil Portrait: By Arthur John Black (1855–1936). This portrait was given to Mundella's daughter, Maria Theresa, who donated it to the Nottingham School Board in 1898 for display at the new Mundella Grammar School. After the school closed in 1985, the portrait was cared for by former students. In 2009, they had it cleaned and loaned it to the Bromley House Library, Nottingham, where it is now displayed.

- Marble Bust: By Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm RA (1834–1890). Working women and children, who benefited from the Factory Act of 1874, collected money (mostly pennies) to create this bust as a tribute to Mundella and his wife. It says: "Presented to Mrs. Mundella by 80,000 factory workers, chiefly women and children, in grateful acknowledgement of her husband's services." It was given to Mary Mundella in Manchester in 1884. The bust remained in the family until it was given to the Nottingham School Board for display at Mundella Grammar School. It is now on loan to the Bromley House Library, Nottingham.

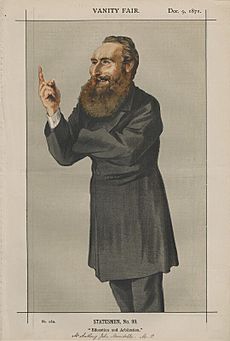

- Caricature (Chromolithograph): By Coïdé, a pen name for James Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836–1902). It was first published in Vanity Fair on December 9, 1871, as part of their "Portraits of Statesmen" series. It is titled "Education and Arbitration." Many copies exist in private and public collections, including the UK Houses of Parliament, the National Portrait Gallery, London, and the University of Sheffield Library.

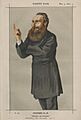

- Caricature (Chromolithograph): By Spy, a pen name for Sir Leslie Matthew Ward (1851–1922). It was first published in Vanity Fair on November 30, 1893. It is a group cartoon portrait with Mundella in the foreground. A copy is owned by the National Portrait Gallery in London.

- Newspaper Cartoons: By various artists. 16 images, all showing caricatures of Mundella, related to the Sheffield parliamentary elections in 1868. They are held by Sheffield University Library.

- Photograph (Platinum Print): By Sir John Benjamin Stone (1838–1914). A late portrait photograph of Mundella, standing at an entrance to the Houses of Parliament, taken in May 1897 (two months before his death). Copies are held by the National Portrait Gallery and the UK Parliament's digital archive.

- Photograph (Woodburytype Carte de Visite): By an unknown photographer. A head and shoulders portrait from the 1870s. A copy is in the National Portrait Gallery.

- Photograph (Albumen Print Cabinet Card): By Alexander Bassano (1829–1913). A head-and-shoulders portrait from 1885. The National Portrait Gallery owns a copy.

- Photograph (Albumen Print): By Cyril Flower, 1st Baron Battersea (1843–1907). A three-quarter-length seated portrait from the 1890s. A copy is held by the National Portrait Gallery.

- Group Portraits: As a leading statesman, Mundella can also be found in many group portraits, photographs, and newspaper illustrations from the late 1800s. Two notable images are in The Illustrated London News: one from February 27, 1869, marking his first speech, and another from August 27, 1892, showing WE Gladstone's new Cabinet.

Images for kids

-

Mundella at the House of Commons by John Benjamin Stone, 1897