Acoma Pueblo facts for kids

|

Acoma

|

|

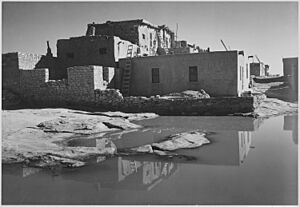

Dwellings on the mesa at Acoma Pueblo

|

|

| Nearest city | Casa Blanca, New Mexico |

|---|---|

| Area | 270 acres (110 ha) |

| Built | 1100 |

| Architectural style | Pueblo, Territorial |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000500 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHLD | October 9, 1960 |

Acoma Pueblo (/ˈækəmə/ ak-Ə-mə, Western Keres: Áakʼu) is a special village built by Native American people. It is located about 60 miles (97 km) west of Albuquerque, New Mexico, in the United States.

The Acoma Pueblo is made up of four main communities: Sky City (also called Old Acoma), Acomita, Anzac, and McCartys. These communities are close to the large Albuquerque metropolitan area. The Acoma Pueblo tribe is officially recognized by the government. Their historical land was once very large, about 5,000,000 acres (2,000,000 ha). Today, most of the Acoma community lives within the Acoma Indian Reservation. Acoma Pueblo is also a National Historic Landmark, which means it is a very important historical place.

In 2010, nearly 5,000 people identified as Acoma. The Acoma people have lived in this area for over 2,000 years. This makes Acoma Pueblo one of the oldest places in the United States where people have lived continuously. Other old pueblos include Taos and Hopi pueblos. Acoma traditions say they have been in their village for more than two thousand years.

Contents

What Does Acoma Mean?

The name Acoma comes from the Spanish word Ácoma. The Spanish got this name from the Acoma word ʔáák’u̓u̓m̓é. This word means 'person from Acoma Pueblo'.

The Acoma word ʔáák’u is the singular form. Some tribal elders say the name means 'place that always was'. Others outside the tribe say it means 'people of the white rock'. It does not mean 'sky city'.

The word Pueblo is a Spanish word. It means 'village' or 'small town'. It is used for both the people and their unique buildings in the southwestern United States.

Language Spoken by Acoma People

The Acoma language is part of the western group of the Keresan language family. Today, most people in Acoma Pueblo speak both Acoma and English. Some older people might also speak Spanish.

History of Acoma Pueblo

How Acoma Began

Pueblo people are thought to be descendants of ancient groups like the Anasazi and Mogollon. Their building styles, farming methods, and art show these influences. In the 1200s, the Anasazi left their canyon homes. This was due to changes in climate and social problems. For about 200 years, people moved around the area.

Acoma Pueblo was established by the 1200s. This early start makes it one of the longest continuously lived-in places in the United States. The Pueblo is built on top of a high, flat hill called a mesa. It is about 365 feet (111 m) tall. This location helped protect the community for over 1,200 years. They wanted to avoid conflicts with nearby tribes like the Navajo and Apache.

First Contact with Europeans

The first time Acoma was mentioned was in 1539. A man named Estevanico, who was a slave, was the first non-Native person to visit Acoma. He told Fray Marcos de Niza about it. Fray de Niza then told the viceroy of New Spain. Estevanico called Acoma the independent Kingdom of Hacus. He said the Acoma people wore turquoise in their ears and noses.

In 1540, Captain Hernando de Alvarado visited Acoma. He was part of conquistador Francisco Vásquez de Coronado's expedition. They called the Pueblo Acuco. Alvarado described it as "a very strange place built upon solid rock." He also said it was "one of the strongest places we have seen." The Pueblo was hard to reach, with only one entrance. This entrance was a stairway built into the rock. It had about 200 steps, then 100 narrower steps. At the very top, people had to climb using holes in the rock. There was a wall at the top where they could roll down stones to protect themselves. On top of the mesa, they had space to grow corn and collect water.

Coronado's group is believed to be the first Europeans to meet the Acoma. Alvarado reported that the Acoma first refused entry. But after threats of attack, the Acoma guards welcomed the Spaniards. The Acoma had clothing made of deerskin, buffalo hide, and cotton. They also had turquoise jewelry, turkeys, bread, and corn. The village seemed to have about 200 men.

The Spanish visited Acoma again in 1581. This was 40 years later, with Fray Agustín Rodríguez and Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado. The Acoma were cautious and fearful. This might have been because the Spanish had enslaved other Native Americans. But the Spanish party eventually convinced them to trade goods for food. Spanish reports said the pueblo had about 500 houses. These houses were three or four stories tall.

In 1582, Antonio de Espejo visited Acoma for three days. He saw that the Acoma wore mantas, which are traditional dresses. Espejo also noticed irrigation in Acomita. This was a farming village near the San Jose River.

Juan de Oñate planned to colonize New Mexico starting in 1595. An Acoma warrior named Zutacapan heard of this plan. He warned the mesa and prepared for defense. However, an elder named Chumpo advised against war. This was partly to prevent deaths. When Oñate visited on October 27, 1598, Acoma met him peacefully. They did not resist Oñate's demand for surrender. Oñate showed his military power by firing a gun salute.

On December 1, 1598, Juan de Zaldívar, Oñate's nephew, came to Acoma. He had 20–30 men. They traded peacefully and waited for an order of ground corn. On December 4, Zaldívar went with 16 armored men to find out about the corn. The Acoma killed 12 of the Spaniards, including Zaldívar. Five men escaped, but one died jumping from the mesa. Four men escaped with the rest of their group.

On December 20, 1598, Oñate learned of Zaldívar's death. He decided to attack Acoma for revenge and to warn other pueblos. Acoma asked other tribes for help. On January 21, 1599, Vicente de Zaldívar (Juan de Zaldívar's brother) arrived at Acoma with 70 soldiers. The Acoma Massacre began the next day and lasted for three days. On January 23, Spanish soldiers climbed the southern mesa without being seen. They entered the pueblo. The Spanish used a cannon, destroying adobe walls. They burned most of the village. About 800 people were killed. This was 13% of the 6,000 people living there. Around 500 others were captured. The pueblo surrendered on January 24. Zaldívar lost only one of his men.

The Spanish cut off the right feet of men over 25 years old. They forced them into slavery for 20 years. Males aged 12–25 and females over 12 were also taken from their families. Most were enslaved for 20 years. The enslaved Acoma were given to government officials and missions. Two other Native American men visiting Acoma had their right hands cut off. They were sent back to their pueblos as a warning. On the north side of the mesa, some houses still show marks from the fire caused by a cannon during this Acoma War. (Oñate was later exiled from New Mexico for bad leadership and cruelty.)

Survivors of the Acoma massacre rebuilt their community between 1599 and 1620. Oñate made the Acoma and other local Native Americans pay taxes. These taxes were paid in crops, cotton, and labor. Spanish rule also brought Catholic missionaries to the area. The Spanish renamed the pueblos with saints' names. They also started building churches. They brought new crops to the Acoma, like peaches, peppers, and wheat.

In 1680, the Pueblo Revolt happened. Acoma participated in this revolt. The revolt brought people from other pueblos to Acoma. Those who later left Acoma moved to form Laguna Pueblo.

The Acoma suffered greatly from smallpox epidemics. They had no natural protection against these diseases from Europe. They also faced attacks from the Apache, Comanche, and Ute tribes. Sometimes, the Acoma would join the Spanish to fight against these nomadic tribes. The Acoma were forced to become Catholic. But they continued to practice their traditional religion in secret. They often combined parts of both religions. Marriage and interaction became common among the Acoma, other pueblos, and Hispanic villages. These communities mixed to form the unique culture of New Mexico.

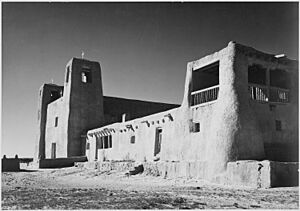

San Esteban Del Rey Mission Church

Between 1629 and 1641, Father Juan Ramirez oversaw the building of the San Estevan Del Rey Mission Church. The Acoma were ordered to build the church. They moved 20,000 short tons (18,000 t) of adobe, straw, sandstone, and mud to the mesa. This was for the church walls. Large Ponderosa pine trees were brought by community members from Mount Taylor. This mountain was over 40 miles (64 km) away. The church is 6,000 square feet (560 m2) in size. It has an altar with 60 feet (18 m)-high wooden pillars. These pillars are hand-carved with red and white designs. These designs show both Christian and Native beliefs. The Acoma know their ancestors built this church. They see it as a very important cultural treasure.

In 1970, the church was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In 2007, it was named a National Trust Historic Site. It is the only Native American site with this ranking.

Acoma in the 1800s and 1900s

During the 1800s, the Acoma people tried to keep their traditional way of life. But they also started to adopt parts of Spanish culture and religion. By the 1880s, railroads brought more settlers. This ended the pueblos' isolation.

In the 1920s, the All Indian Pueblo Council met for the first time in over 300 years. They responded to Congress wanting to take Pueblo lands. The U.S. Congress passed the Pueblo Lands Act in 1924. The Acoma succeeded in keeping their land. However, they faced challenges in the 1900s trying to keep their cultural traditions. Protestant missionaries opened schools in the area. The Bureau of Indian Affairs forced Acoma children into boarding schools. By 1922, most children were in these schools. They were forced to speak English and practice Christianity. Several generations lost touch with their own culture and language. This had harsh effects on their families and societies.

Acoma Today

Today, about 300 adobe buildings stand on the mesa. They are two or three stories tall. Outside ladders are used to reach the upper levels where people live. A road was blasted into the rock in the 1950s to reach the mesa. About 30 people live permanently on the mesa. The population grows on weekends when family members visit. Around 55,000 tourists visit each year for the day.

Acoma Pueblo on the mesa has no electricity, running water, or sewage systems. A reservation surrounds the mesa, covering about 600 square miles (1,600 km2). Tribal members live both on and off the reservation. Acoma culture today remains somewhat private. According to the 2000 United States census, 4,989 people identify as Acoma.

Acoma Culture

Leadership and Land

Acoma's government was traditionally led by two people. One was a cacique, or head of the Pueblo. The other was a war captain. Both served until they died. They had strong religious connections to their roles. The Spanish later created a group to oversee the Pueblo. But the Acoma did not take their power seriously. This Spanish group handled outside matters. It included a governor, two lieutenant governors, and a council. The Acoma also took part in the All Indian Pueblo Council. This council started in 1598 and was revived in the 1900s.

The Acoma control about 500,000 acres (200,000 ha) of their traditional land. This land has mesas, valleys, hills, and arroyos. The average height is about 7,000 feet (2,100 m). It gets about 10 inches (250 mm) of rain each year. Since 1977, the Acoma have bought more land. On the reservation, only tribal members can own land. Almost all enrolled members live on the property. The cacique is still active in the community. This leader is from the Antelope clan. The cacique appoints tribal council members, staff, and the governor.

In 2011, Acoma Pueblo and the Pueblo of Santa Clara experienced heavy flooding. New Mexico provided over $1 million for emergency help and repairs. Governor Susana Martinez asked for more money from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Buildings and Homes

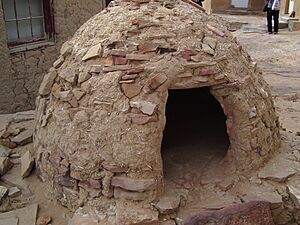

Acoma Pueblo has three rows of three-story buildings. They are built like apartments. They face south on top of the mesa. The buildings are made from adobe brick. Beams cross the roof. These beams were covered with poles, brush, and then plaster. The roof of one level serves as the floor for the level above it. Each level is connected by ladders. These ladders were also a way to defend the village. The traditional design has no windows or doors on the ground floor. The lower levels were used for storage. Baking ovens are outside the buildings. Water is collected from two natural cisterns. Acoma also has seven rectangular kivas. These are special rooms for religious ceremonies. The village plaza is the spiritual center.

Family Life and Education

About 20 matrilineal clans were recognized by the Acoma. This means family lines were traced through the mother. Traditional child-rearing involved very little strict discipline. Couples were usually monogamous, meaning they had one partner. Divorce was rare. After a death, a quick burial happened. Then, there were four days and nights of vigil. Women wore cotton dresses and sandals or high moccasin boots. Men wore cotton kilts and leather sandals. Rabbit and deer skin were also used for clothing and robes. In the 1600s, the Spanish brought horses to the Pueblo.

Education was led by kiva headmen. They taught about human behavior, spirit and body, astrology, and ethics. They also taught child psychology, public speaking, history, dance, and music. Since the 1970s, Acoma Pueblo has controlled its own education services. This has helped keep traditional and modern ways of life alive. They share a high school with Laguna Pueblo. Alcohol is not allowed on the Pueblo. The community is served by the Acoma-Canoncito-Laguna (ACL) Hospital. This hospital is run by Indian Health Services and is in Acoma. Today, 19 clans are still active.

Religion and Beliefs

Traditional Acoma religion focuses on living in harmony with nature. The sun represents the Creator deity. The mountains around the community, the sun above, and the earth below help balance the Acoma world. Traditional religious ceremonies often involve the weather. For example, they seek to ensure good rainfall. The Acoma also use kachinas in their rituals. These are spiritual beings. The Pueblos also had one or more kivas. These were special religious rooms. The leader of each Pueblo was the community's religious leader, or cacique. The cacique would watch the sun. They used it to schedule ceremonies, some of which were kept secret.

Many Acoma people are Catholic. But they often mix parts of Catholicism with their traditional religion. Many old rituals are still performed. In September, the Acoma honor their patron saint, Saint Stephen. For this feast day, the mesa is open to the public for celebration. More than 2,000 people attend the San Esteban Festival. The celebration starts at San Esteban Del Rey Mission. A carved pine effigy (statue) of Saint Stephen is taken from the altar. It is carried into the main plaza. People chant, shoot rifles, and ring steeple bells. The procession goes past the cemetery, down narrow streets, and to the plaza. When it reaches the plaza, the effigy is placed in a shrine. This shrine is lined with woven blankets and guarded by two Acoma men. A celebration with dancing and feasting follows. During the festival, vendors sell goods like traditional pottery and food.

Food and Farming

Before meeting the Spanish, Acoma people mainly ate corn, beans, and squash. Mut-tze-nee was a popular thin corn bread. They also raised turkeys, tobacco, and sunflowers. The Acoma hunted antelope, deer, and rabbits. They gathered wild seeds, berries, nuts, and other foods. After 1700, new foods were recorded. These included blue corn drink, pudding, corn mush, corn balls, wheat cake, and paper bread. They also ate flour bread, wild berries, and prickly pear fruit. After contact with the Spanish, they raised goats, horses, sheep, and donkeys.

Today, other foods are popular in Acoma. These include apple pastries, corn tamales, green-chili stew with lamb, fresh corn, and wheat pudding with brown sugar.

They used Irrigation methods like dams and terraces for farming. Farming tools were made of wood and stone. Harvested corn was ground by hand using a mortar.

Economy and Tourism

Historically, Acoma's economy was communal. Labor was shared, and food was distributed equally. They had large trading networks. These spread thousands of miles across the region. Trading fairs were held at certain times in the summer and fall. The largest fair was in Taos, run by the Comanche. Nomadic traders exchanged slaves, buckskins, buffalo hide, jerky, and horses. Pueblo people traded for copper and shell ornaments, macaw feathers, and turquoise. Since 1821, the Acoma traded using the Santa Fe Trail. When railroads arrived in the 1880s, the Acoma became dependent on American-made goods. This reduced traditional arts like weaving and pottery.

Today, the Acoma produce many goods. They grow alfalfa, oats, wheat, chilies, corn, melon, squash, vegetables, and fruit. They also raise cattle. They have natural gas, geothermal, and coal resources. Uranium mines in the area provided jobs for the Acoma. But these mines closed in the 1980s. After that, the tribe became the main employer. However, high unemployment rates are a problem for the Pueblo. The uranium mines left radiation pollution. This caused the tribal fishing lake to be drained. It also led to some health problems in the community.

Visiting Acoma Pueblo

Tourism is a big source of income for the tribe. In 2008, Pueblo Acoma opened the Sky City Cultural Center and Haak'u Museum. It is at the base of the mesa. The original center was destroyed by fire in 2000. The new center and museum aim to keep Acoma culture alive. Films about Acoma history are shown. A café serves traditional foods. The buildings were inspired by pueblo design. They have wide doorways in the middle, like traditional homes. These wide doors made it easier to bring in supplies. The windowpanes have small pieces of mica. This mineral was used to make windows in mesa homes. The complex is also fire-resistant, unlike traditional pueblos. It is painted in light pinks and purples to match the surrounding landscape. Traditional Acoma artwork is shown and demonstrated at the center. This includes ceramic chimneys made on the rooftop. Arts and crafts also bring income.

Acoma Pueblo is open to the public for guided tours from March to October. It closes for cultural activities in June and July. Taking photos of the Pueblo and surrounding land is limited. Tours and camera permits are bought at the Sky City Cultural Center. While photography is allowed with a permit, video recordings, drawings, and sketching are not. All photography is forbidden inside the church.

The Acoma Pueblo also has a casino and hotel called the Sky City Casino Hotel. The casino and hotel do not serve alcohol. They are managed by the Acoma Business Enterprise. This group oversees most Acoma businesses.

Acoma Arts

At Acoma, pottery is one of the most famous art forms. Men create weavings and silver jewelry.

Pottery Making

Acoma pottery has been made for over 1,000 years. Dense local clay, dug from a nearby site, is key to Acoma pottery. The clay is dried and made stronger by adding crushed pottery shards. The pieces are then shaped, painted, and fired. Traditional designs include geometric patterns, thunderbirds, and rainbows. These designs are applied using the spike of a yucca plant. After finishing a pot, a potter would lightly tap its side. They would hold it to their ear. If the pot did not ring, it would crack during firing. If this happened, the piece was destroyed. Its shards were then used for future pots.

Acoma Communities

Notable Acoma People

- Loren Aragon, fashion designer

- Marie Chino, traditional pottery artist

- Vera Chino, traditional pottery artist

- Lucy Lewis, traditional pottery artist

- Georgene Louis, attorney and member of the New Mexico House of Representatives

- Simon J. Ortiz, poet, author, and educator

- Anton Docher, "The Padre of Isleta", French priest

- Rachel Concho, traditional pottery artist known for seed pots

Images for kids

-

Acoma water girls by Edward S. Curtis

-

Fineline black-on-white olla by Lucy M. Lewis, c. 1960–1970s, collection of the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art

See also

In Spanish: Pueblo de Acoma para niños

In Spanish: Pueblo de Acoma para niños