Wildfire facts for kids

A wildfire is a big, unplanned fire that burns in wild areas like forests, grasslands, or bushes. You might hear them called forest fires, bushfires (especially in Australia), or wildland fires. They are different from "controlled burns," which are small fires set on purpose by experts to help the land or prevent bigger fires later. Sometimes, controlled burns can accidentally turn into wildfires.

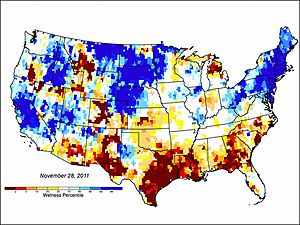

Wildfires are often grouped by how they start, what they burn, and how the weather affects them. How a wildfire behaves depends on things like the types of plants available to burn, the landscape, and the weather. When there's a lot of rain, plants grow a lot. Then, if there's a long dry and hot period, these plants become very easy to burn, leading to big wildfires. Climate change is making these dry and hot periods even worse.

Wildfires that start naturally can actually be good for plants, animals, and ecosystems that have grown used to fire. Many plants need fire to grow and make new seeds. Some forests even depend on wildfires to stay healthy. Big, intense wildfires can create special habitats called "snag forests" (areas with many dead trees). These areas can have more different kinds of plants and animals than old, unburned forests.

However, wildfires can also cause serious problems for people. They can harm people's health through smoke, destroy homes and buildings (especially where wild areas meet towns), cause economic losses, and pollute water and soil.

Wildfires are a common type of natural disaster in places like Siberia, California, British Columbia, and Australia. Areas with Mediterranean climates or in the taiga (cold forest) regions are especially likely to have them. Around the world, human actions have made wildfires worse. The amount of land burned by wildfires has doubled compared to natural levels. Humans have affected wildfires through climate change, changing how land is used, and trying to stop all fires. In the U.S., more severe fires release stored carbon back into the air, which adds to the greenhouse effect and makes climate change worse.

Contents

How Wildfires Start

Fires usually start either naturally or because of human activity.

Natural Causes

Natural things that can start wildfires without people include lightning, volcanic eruptions, sparks from falling rocks, and spontaneous combustion (when something catches fire by itself).

Human Activity

Fires caused by people can come from arson (setting fires on purpose), accidents, or uncontrolled use of fire for clearing land or farming. In warm, wet areas, farmers often use a "slash-and-burn" method to clear fields during the dry season.

In places with moderate climates, the most common human causes of wildfires are sparks from equipment (like chainsaws or mowers), overhead power lines, and arson.

Arson can cause over 20% of human-caused fires. However, sometimes false information about arson spreads online, like during the 2019–20 Australian bushfire season or the 2023 Canadian wildfires. In California, about 6–10% of wildfires each year are caused by arson.

Fires in coal seams burn underground in thousands of places worldwide. These can unexpectedly flare up and ignite nearby plants.

How Wildfires Spread

How wildfires spread depends on the type of plants available, how they are arranged, how wet they are, and the weather. The shape of the land also affects how plants grow, which then affects the fire. Wildfires can be grouped by what they burn:

- Ground fires burn slowly underground, feeding on roots, decaying leaves, and other buried plant material. They can burn for days or months, like peat fires in Indonesia.

- Surface fires burn low-lying plants on the ground, such as leaves, fallen branches, grass, and small bushes. These fires usually burn at lower temperatures and spread slowly, but steep slopes and wind can make them spread faster.

- Ladder fires burn material between low plants and tree tops, like small trees, fallen logs, and vines. Invasive plants that climb trees can also help ladder fires spread.

- Crown fires (or canopy fires) burn the tops of tall trees, vines, and mosses. For a crown fire to start, the tree tops need to be dense and continuous, and there must be enough surface and ladder fires below. These fires can spread into places like the Amazon rain forest, harming ecosystems not used to heat.

What Wildfires Need to Burn

Wildfires happen when the three parts of the "fire triangle" come together: a spark, something to burn (like plants), and enough oxygen from the air. If plants are very wet, they usually won't catch fire easily because it takes a lot of heat to dry out the water first.

Forests with many dense trees usually have more shade, which means cooler temperatures and more humidity. This makes them less likely to have wildfires. Lighter materials like grasses and leaves catch fire more easily because they hold less water than thicker branches or tree trunks. Plants constantly lose water, but they usually get enough water from the soil, humidity, or rain. When there's a drought and they don't get enough water, plants dry out and become very flammable.

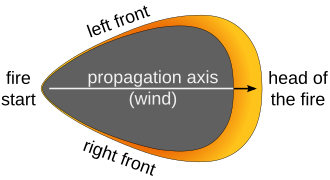

The wildfire front is where the fire is actively burning and unburned material meets the flames. As the fire front gets closer, it heats the air and plants around it. First, water in the wood turns into steam at 100 °C (212 °F). Then, at 230 °C (450 °F), the wood breaks down and releases flammable gases. Finally, wood can smolder at 380 °C (720 °F) or burst into flames at 590 °C (1,000 °F). Even before the flames arrive, the heat from the fire front can warm the air to 800 °C (1,470 °F). This pre-heats and dries out plants, making them catch fire faster and helping the fire spread quickly.

Wildfires can spread very fast, moving up to 10.8 kilometres per hour (6.7 mph) in forests and 22 kilometres per hour (14 mph) in grasslands. They can also spread by spotting, where winds carry hot embers or burning materials through the air over roads, rivers, or other barriers. These embers can start new fires, called spot fires, far away from the main fire. In Australian bushfires, spot fires have been known to start as far as 20 kilometres (12 mi) from the main fire.

Very large wildfires can create their own weather. As air gets heated, it rises, creating strong updrafts that pull in cooler air from nearby areas. This can form pyrocumulus clouds (fire clouds), strong winds, and even fire whirls (like small tornadoes) that can spin at over 80 kilometres per hour (50 mph). Fast-spreading fires, many crown fires, spotting, fire whirls, and strong updrafts all show extreme fire conditions.

Fire Intensity Changes Day and Night

Wildfire intensity usually increases during the day. Burning logs smolder up to five times faster during the day because of lower humidity, higher temperatures, and stronger winds. Sunlight warms the ground during the day, creating air currents that travel uphill. At night, the land cools, creating air currents that travel downhill. Wildfires are pushed by these winds and often follow the air currents over hills and through valleys. Firefighters often plan their work around a "fire day" that starts at 10:00 a.m. because they know fires will get more intense as the day warms up.

Preventing Wildfires

Wildfire prevention means taking steps to lower the chance of fires starting and to make them less severe if they do. These methods aim to keep the air clean, maintain healthy ecosystems, protect resources, and affect future fires. Since most forest fires in Europe (95%) are caused by people, prevention plans must consider human actions.

Wildfire prevention programs around the world use techniques like "wildland fire use" and "controlled burns." Wildland fire use means letting naturally caused fires burn under careful watch. Controlled burns are fires started on purpose by government agencies when the weather is safe. These burns help keep forests, grasslands, and wetlands healthy and support different kinds of plants and animals.

One common and cheap way to reduce wildfire risk is controlled burning. This involves intentionally starting smaller, less intense fires to burn away extra plants and debris that could fuel a big wildfire. This also helps keep many different plant species healthy. Some people believe controlled burns are the cheapest and best way to manage many forests.

Building rules in areas prone to fires often require homes to be built with fire-resistant materials. Also, a "defensible space" must be kept around buildings by clearing away flammable materials. Some communities also create wide "fire lines" (5 to 10 meters (16 to 33 ft)) between forests and their villages, and they patrol these lines during dry seasons.

Finding Wildfires Early

Getting quick and accurate information about fires is very important for fighting them. Early detection helps firefighters respond quickly. In the past, fire lookout towers were used, and fires were reported by telephone or even carrier pigeons. Later, infrared scanning was developed. However, sharing information was often slow.

Today, public hotlines, fire lookout towers, and patrols on the ground and in the air help find fires early. But human observation can be limited by tiredness or weather. Electronic systems are becoming more popular to help. These systems can be partly or fully automated, using cameras and sensors to detect smoke or heat. They can combine satellite data, aerial images, and GPS information to give firefighters real-time updates.

Local Sensors and Satellites

Small, high-risk areas with thick plants or near cities can be watched using local sensor networks. These systems can include wireless sensor networks that act like automated weather stations, checking temperature, humidity, and smoke. Some can even recharge their batteries using small electrical currents from plants. Larger areas can be watched by scanning towers with fixed cameras and sensors that detect smoke or infrared heat from fires. Some cameras have night vision and can detect changes in brightness or color.

Companies are using new technology. For example, PanoAI installs 360-degree "rapid detection" cameras on cell towers that can watch a 15-mile area 24/7. Sensaio Tech has sensor devices that monitor 14 different forest conditions, sending live data and alerts to clients.

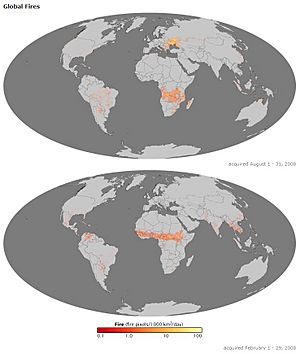

Satellites and aircraft (planes, helicopters, or drones) can provide a wider view for very large, low-risk areas. These systems use GPS and infrared or high-resolution cameras to find wildfires. Satellite sensors can measure heat from fires, finding hot spots. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) uses satellite data to map fire and smoke locations. However, satellite detection can have small errors, and clouds can block the view.

New tools are being developed. The U.S. Forest Service uses data from the Suomi NPP satellite to find smaller fires in more detail. This data is used with computer models to predict how a fire will move based on weather and land. Drones using artificial intelligence (AI) are also being developed. Data Blanket has drones that can fly themselves to assess wildfires, providing real-time info like local plants and fuels. Other companies are launching satellites with infrared sensors to quickly detect temperature changes and predict fire growth.

Artificial Intelligence

Between 2022 and 2023, wildfires in North America led to a big increase in new technologies using artificial intelligence for finding, preventing, and predicting wildfires early.

Fighting Wildfires

How wildfires are fought depends on the technology available. In some places, people might throw sand or beat the fire with sticks. In more developed countries, advanced methods are used. Fire retardants and water can be dropped from unmanned aerial vehicles, planes, and helicopters. Most wildfires are put out before they get too big. However, fires that escape during extreme weather are very hard to stop without a change in the weather. Wildfires in Canada and the U.S. burn an average of 54,500 square kilometers (13,000,000 acres) each year.

Fighting wildfires is very dangerous. A fire's front can change direction suddenly or jump across fire breaks. Intense heat and smoke can make firefighters confused, making fires especially risky. Firefighters face dangers like heat stress, tiredness, smoke, dust, burns, cuts, and animal bites. Many wildland firefighters have died while on duty.

Smoke from wildfires contains gases like carbon monoxide and tiny particles. These can cause breathing problems and heart issues. Firefighters try to reduce smoke exposure by rotating crews, avoiding fighting fires downwind, and using equipment instead of people where smoke is heavy. Camps should also be located upwind of fires.

Fire Retardants

Fire retardants are used to slow wildfires by stopping them from burning. They are usually watery solutions with chemicals similar to fertilizers. The decision to use retardant depends on the fire's size, location, and strength. Sometimes, it's used as a prevention measure.

Fire retardants can affect water quality, but the impact depends on how much water is in the area and how much rain falls. Wildfire ash and debris can also clog rivers and reservoirs, increasing the risk of floods and damaging water treatment systems. More research is needed on the long-term effects of fire retardants on land, water, and wildlife. On the good side, the nitrogen and phosphorus in fire retardants can act like fertilizer for poor soils, temporarily helping plants grow.

Wildfires and the Environment

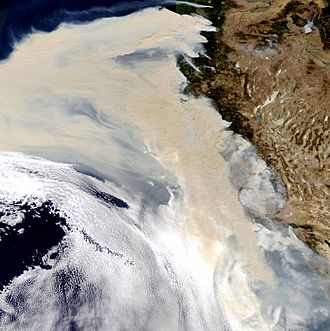

Impact on Air

Most of Earth's weather and air pollution are in the troposphere, the lowest part of the atmosphere. Large wildfires can create strong updrafts that push smoke, soot, and other tiny particles high into the atmosphere, even into the lower stratosphere. Smoke plumes from wildfires can travel over 1,600 kilometers (1,000 mi).

Wildfires can increase local air pollution and release carbon dioxide into the air. Wildfire smoke contains fine particles that can cause heart and breathing problems. Too many fire byproducts in the air can also increase ozone levels beyond safe limits.

Impact on Ecosystems

Wildfires are common in places that get enough rain for plants to grow but also have long, dry, hot periods. This includes parts of Australia, Southeast Asia, southern Africa, the United States, Canada, and the Mediterranean region.

Big, intense wildfires create "snag forest" habitats, which often have more different kinds of plants and animals than unburned old forests. Many plants and animals in North American forests have evolved with fire and depend on it to reproduce and grow. Fire helps return nutrients from dead plants back to the soil. The heat from fire is needed for some seeds to sprout. Dead trees and new forests created by intense fires provide good homes for wildlife.

However, some ecosystems suffer from too much fire, like the chaparral in southern California. More frequent fires in these areas disrupt natural cycles, harm native plants, and encourage the growth of non-native weeds. Invasive plants can grow quickly in fire-damaged areas. Because they are very flammable, they can increase the risk of future fires, creating a cycle that leads to even more fires and changes native plant communities.

In the Amazon rainforest, drought, logging, cattle farming, and slash-and-burn agriculture damage fire-resistant forests and encourage flammable brush to grow. This creates a cycle that leads to more burning. Fires in the rainforest threaten its many different species and release large amounts of carbon dioxide. Fires, along with drought and human activity, could damage or destroy more than half of the Amazon rainforest by 2030. Wildfires also create ash, reduce nutrients in the soil, and cause more water runoff, leading to erosion and flash floods.

Impact on Waterways

Debris and chemicals washing into waterways after wildfires can make drinking water unsafe. Research shows that the amount of many pollutants in water increases after a fire. These impacts can happen during the fire and for years afterward. Increases in nutrients and sediments can occur within a year, while heavy metal levels might peak 1-2 years after a wildfire.

Chemicals like benzene have been found in drinking water systems after wildfires. Benzene can get into plastic pipes and take a long time to be removed. Temperature increases from fires can also cause plastic water pipes to release toxic chemicals.

Impact on Plants and Animals

Wildfires can affect plants and animals in many ways. Some species are adapted to fire and even need it for their life cycle. Others are harmed by fire, especially if fires become too frequent or intense.

Wildfires and People

Wildfire risk is the chance that a wildfire will start or reach a certain area, and how much damage it could cause to human lives and property. This risk depends on human activities, weather, how much fuel (plants) is available, and how many resources are there to fight a fire. Wildfires have always been a threat to people. However, human-caused changes to the land and climate are making people face wildfires more often and increasing the risk. It's thought that the increase in wildfires comes from a century of trying to stop all fires, combined with more people building homes in wild areas prone to fire. Global warming and climate change are causing higher temperatures and more droughts, which also increase wildfire risk.

Health Dangers from Smoke

The most obvious bad effect of wildfires is property destruction. But dangerous chemicals released by fires also greatly affect human health.

Wildfire smoke is mostly carbon dioxide and water vapor. It also contains smaller amounts of carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, and tiny airborne particles. About 80–90% of wildfire smoke consists of very fine particles, 2.5 micrometers in diameter or smaller.

Carbon monoxide and fine particulate matter are the main health threats. High levels of heavy metals like lead and arsenic have been found in ash after wildfires. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) created the air quality index (AQI) to help people know how much pollution is in the air.

Health Effects

Breathing in smoke from a wildfire can be bad for your health. Wildfire smoke is made of things that burn, like carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, water vapor, tiny particles, and other chemicals. The biggest health worries are breathing in the particles and carbon monoxide.

Particulate matter (PM) is tiny bits of dust and liquid droplets in the air. They are grouped by size. Coarse particles are filtered by the upper airways and can cause eye and sinus irritation, sore throats, and coughing. Smaller particles go deeper into the lungs and even into the bloodstream, causing problems. These tiny particles can cause inflammation and damage to lung cells. This is especially harmful for people with breathing problems like asthma or COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Symptoms can include wheezing, shortness of breath, chest pain, and a fast heart rate.

Asthma and Smoke

Studies show a clear link between air pollution and breathing problems like asthma. Smoke from wildfires can make asthma worse. Children are especially at risk. Exposure to air pollution during pregnancy or early childhood might affect how lungs develop and increase the risk of asthma.

Carbon Monoxide Danger

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a gas you can't see or smell. It's most concentrated near a smoldering fire, making it a serious danger for firefighters. When inhaled, CO gets into the bloodstream and reduces the amount of oxygen that reaches your body's important organs. High levels can cause headaches, weakness, confusion, and even death. Even at lower levels, people with heart disease might feel chest pain.

Wildfires can also affect mental health. People, both adults and children, who have been directly or indirectly affected by wildfires have shown signs of mental health issues like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and phobias.

After the Fire Risks

Even after a wildfire is out, dangers remain. People returning home might be at risk from trees weakened by fire that could fall. Humans and pets can also fall into "ash pits" (hot spots hidden under ash). Wildfires can also damage electrical systems.

Other risks can increase if extreme weather follows a fire. For example, wildfires make soil less able to absorb rain, so heavy rainfall can lead to more severe flooding and mud slides.

Wildfires in Culture

Wildfires are part of many cultures. The phrase "to spread like wildfire" means something that quickly becomes known by many people.

In ancient Greece, wildfire activity was a big factor in how society developed. In modern Greece, like in many other places, it's the most common natural disaster and plays a big role in people's lives.

In 1937, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt started a campaign to prevent fires, showing how human carelessness caused forest fires. Later, posters featured Uncle Sam, Disney's Bambi, and the official mascot of the U.S. Forest Service, Smokey Bear. The Smokey Bear campaign is very popular in the United States.

Wildfires also have indirect effects on society, like utilities needing to prevent their equipment from starting fires, and homeowners in fire-prone areas sometimes losing their insurance.

Related pages

Images for kids

-

Experimental fire in Canada

-

A Pyrocumulus cloud produced by a wildfire in Yellowstone National Park

-

Elk Bath, an award winning photograph of elk avoiding a wildfire in Montana

-

Aerial view of deliberate wildfires on the Khun Tan Range, Thailand. These fires are lit by local farmers every year in order to promote the growth of a certain mushroom

-

1985 Smokey Bear poster with part of his admonition, "Only you can prevent forest fires".

-

Wildfires across the Balkans in late July 2007 (MODIS image)

-

Smoke from the 2020 California wildfires settles over San Francisco

See also

In Spanish: Incendio forestal para niños

In Spanish: Incendio forestal para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |