Taiga facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Taiga |

|

|---|---|

Jack London Lake in the Kolyma region of Russia.

|

|

The taiga is a huge forest in the northern parts of the world, between the tundra to the north and temperate forests to the south.

|

|

| Ecology | |

| Biome |

|

| Geography | |

| Countries |

|

| Climate type |

|

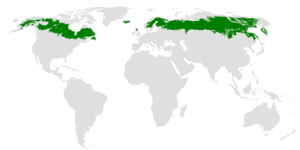

The taiga (pronounced TY-gə), also known as the boreal forest or snow forest, is a huge forest biome. It is famous for its cone-bearing coniferous trees, like pines, spruces, and larches. The taiga is the world's largest land biome, covering large parts of our planet.

In North America, the taiga stretches across most of inland Canada and Alaska. It also covers small parts of the northern United States. In Eurasia, it covers most of Sweden, Finland, and Norway. It also stretches across much of Russia, from Europe to the Pacific Ocean.

The types of trees in the taiga change depending on the location. In North America, spruce trees are most common. In Scandinavia, you will find a mix of spruce, pine, and birch trees. The Russian taiga has spruce, pine, and larch trees.

The taiga is a fairly young biome. It formed about 12,000 years ago after the last ice age. Before that, much of this land was covered by giant ice sheets.

The term "taiga" can mean different things. In North America, people often use "boreal forest" for the southern parts of the forest. They use "taiga" for the colder, more empty areas near the tundra.

Climate change is a major threat to the taiga. It affects the trees, animals, and the entire ecosystem.

Contents

A World of Cold and Snow

The taiga covers about 11.5% of the Earth's land. It is the second-largest biome after deserts. The biggest areas of taiga are in Russia and Canada.

Freezing Winters, Short Summers

The taiga is one of the coldest biomes on Earth, after the ice caps and tundra. The average temperature for the year is usually between -5 °C and 5 °C (23 °F and 41 °F).

Winters are very long and extremely cold. A typical winter day might be around -20 °C (-4 °F). Summers are short, lasting only one to three months. But they can be warm and humid, with an average temperature of 18 °C (64 °F).

In some parts of Siberia, the winter temperatures can be the coldest in the Northern Hemisphere.

A Short Time to Grow

The growing season is the time of year when plants can grow. In the taiga, this season is very short, often between 50 and 100 days.

However, the taiga is located at high latitudes. This means summer days are very long. The sun can stay in the sky for almost 20 hours a day. This extra sunlight helps plants grow quickly during the short summer. In areas inside the Arctic Circle, the sun never sets in the middle of summer!

Rain and Snow

The taiga gets a low amount of precipitation. This is usually between 200 and 750 mm (8 to 30 inches) per year. Most of it falls as rain during the summer.

In winter, it snows a lot. The snow can stay on the ground for up to nine months in the most northern parts of the taiga. The snow helps protect the soil and plant roots from the extreme cold.

A Land Shaped by Ice

Long ago, giant sheets of ice called glaciers covered most of the taiga. As these glaciers moved and later melted, they carved out the land. They left behind many holes that filled with water.

This is why the taiga has so many lakes and bogs. A bog is a type of wet, spongy ground. These wetlands are an important part of the taiga ecosystem.

-

The taiga near Verkhoyansk, Russia. It has some of the coldest winters but can have warm summer days.

The Forest Floor

The soil in the taiga is usually young and does not have many nutrients. The cold climate slows down the process of dead plants breaking down into healthy soil.

The needles from evergreen trees are acidic. When they fall, they make the soil acidic too. This makes it hard for many plants to grow. Usually, only lichens and some mosses can grow on the forest floor. In sunny clearings, more herbs and berries can grow.

The Amazing Plants of the Taiga

The taiga has two main types. The southern part is a closed canopy forest. Here, the trees grow very close together. The northern part is a lichen woodland or sparse taiga. Here, the trees are more spread out.

The boreal forest is also home to many types of berries. These include wild strawberries, cranberries, cloudberries, and lingonberries.

The Conifer Kings

The forests of the taiga are mostly made of coniferous trees. These include larch, spruce, fir, and pine. These trees are experts at surviving in the cold.

- Evergreen Needles: Most conifers are evergreen. They keep their needles all year. This lets them start making food from sunlight as soon as the weather warms up. The needles also have a waxy coating that helps save water.

- Cone Shape: The cone shape of these trees helps snow slide off their branches. This stops the branches from breaking under the weight of heavy snow.

- Shallow Roots: The soil is thin, so trees have shallow roots to get nutrients from the top layer.

Other Plants

Although conifers are the most common, some broadleaf trees also grow in the taiga. These include birch, aspen, and willow. They usually grow in the warmer, southern parts of the biome.

Many smaller plants like ferns, mosses, and wildflowers grow on the forest floor where they can find sunlight.

Animals of the North

The taiga is home to many animals that have adapted to the cold climate. Canada's boreal forest alone has 85 species of mammals and 130 species of fish.

The cold winters are tough for reptiles and amphibians. Only a few species live here, like the common garter snake and the wood frog. They survive by hibernating underground during the winter.

Fish in the taiga can live in very cold water, even under ice. Common fish include the northern pike, walleye, and various types of grayling and lake whitefish.

Big Plant-Eaters

The taiga is home to large herbivorous mammals. These include the moose and the reindeer (called caribou in North America). In some southern parts of the taiga, you can also find elk and roe deer. The largest animal in the taiga is the wood bison, found in northern Canada and Alaska.

Mighty Predators

Predators in the taiga have to be able to travel long distances to find food. These animals include the Canada lynx, wolverine, wolf, red fox, and several species of bear, like the grizzly bear and American black bear. In the far eastern parts of Russia, the giant Siberian tiger also lives in the taiga.

Small but Tough Mammals

Many small mammals live in the taiga. These include beavers, squirrels, chipmunks, and snowshoe hares. Some of these animals hibernate during the winter. Others grow thick fur coats to stay warm.

Birds of the Forest

Over 300 species of birds come to the taiga to nest in the summer. They enjoy the long days and the huge number of insects. Most of these birds migrate south for the winter.

Only about 30 species of birds stay in the taiga all year. These include the golden eagle, great gray owl, raven, and crossbill. They survive by eating seeds or hunting other animals.

The Role of Wildfires

Wildfires are a natural and important part of the taiga ecosystem. Lightning often starts fires that can burn huge areas of forest.

These fires might seem destructive, but they are actually helpful.

- Clearing the Forest: Fires clear out old and dead trees. This makes room for new plants to grow.

- Helping Seeds Sprout: Some trees, like the jack pine, have special cones that only open after a fire. The fire's heat melts the resin on the cones, releasing the seeds onto the newly cleared ground.

- Returning Nutrients: Fire burns dead material on the forest floor. This returns nutrients to the soil, helping new plants grow strong.

The taiga landscape is a patchwork of forests of different ages, all shaped by a long history of fire.

Challenges Facing the Forest

The taiga is facing several threats that could change it forever.

A Changing Climate

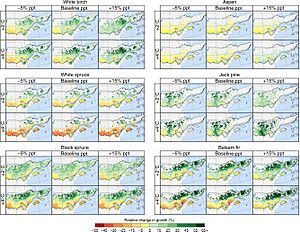

In recent years, the northern parts of the world have warmed up faster than other places. This climate change is a big problem for the taiga.

- Drier Conditions: Warmer summers can cause drought, which stresses the trees and makes them weaker.

- Forests on the Move: As the climate warms, the taiga may slowly move north into the tundra. At the same time, its southern edge may turn into grassland.

- Insect Outbreaks: Warmer winters allow tree-killing insects, like the spruce bark beetle, to survive and spread.

Human Impact

People also have a big impact on the taiga. Some of the larger cities in this biome include Murmansk in Russia and Anchorage in the United States.

Large areas of the taiga, especially in Siberia, have been harvested for lumber. This is called logging. While wood is a useful resource, cutting down too many trees can damage the forest ecosystem.

Protecting the Boreal Forest

The taiga is very important for the health of our planet. It is sometimes called the "lungs of the planet" because its trees produce so much oxygen.

The taiga also stores enormous amounts of carbon in its trees, soil, and wetlands. It stores more carbon than all the world's temperate and tropical forests combined. This helps to slow down climate change.

Many people and governments are working to protect the taiga. They are creating large protected areas where activities like logging and mining are not allowed. For example, in 2010, the Canadian government created a new park reserve to protect 13,000 square kilometers of boreal forest. Protecting these amazing snow forests is important for the future of our world.

Taiga ecoregions

|

Palearctic boreal forests/taiga ecoregions

|

|

|---|---|

| East Siberian taiga | Russia |

| Iceland boreal birch forests and alpine tundra | Iceland |

| Kamchatka–Kurile meadows and sparse forests | Russia |

| Kamchatka–Kurile taiga | Russia |

| Northeast Siberian taiga | Russia |

| Okhotsk–Manchurian taiga | Russia |

| Sakhalin Island taiga | Russia |

| Scandinavian and Russian taiga | Finland, Norway, Russia, Sweden |

| Trans-Baikal conifer forests | Mongolia, Russia |

| Urals montane tundra and taiga | Russia |

| West Siberian taiga | Russia |

|

Nearctic boreal forests/taiga ecoregions

|

|

|---|---|

| Alaska Peninsula montane taiga | United States |

| Central Canadian Shield forests | Canada |

| Cook Inlet taiga | United States |

| Copper Plateau taiga | United States |

| Eastern Canadian forests | Canada |

| Eastern Canadian Shield taiga | Canada |

| Interior Alaska–Yukon lowland taiga | Canada, United States |

| Mid-Continental Canadian forests | Canada |

| Midwestern Canadian Shield forests | Canada |

| Muskwa–Slave Lake forests | Canada |

| Newfoundland Highland forests | Canada |

| Northern Canadian Shield taiga | Canada |

| Northern Cordillera forests | Canada |

| Northwest Territories taiga | Canada |

| South Avalon–Burin oceanic barrens | Canada, France (Saint Pierre and Miquelon) |

| Southern Appalachian spruce–fir forest | United States |

| Southern Hudson Bay taiga | Canada |

| Yukon Interior dry forests | Canada |

Images for kids

-

The taiga in the river valley near Verkhoyansk, Russia, at 67°N, experiences the coldest winter temperatures in the northern hemisphere, but the extreme continentality of the climate gives an average daily high of 22 °C (72 °F) in July

See also

In Spanish: Taiga para niños

In Spanish: Taiga para niños