John Calvin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Calvin

|

|

|---|---|

Anonymous portrait, c. 1550

|

|

| Born |

Jehan Cauvin

10 July 1509 Noyon, Picardy, France

|

| Died | 27 May 1564 (aged 54) |

| Education | University of Paris University of Orléans University of Bourges |

| Occupation | Reformer, minister, author |

|

Notable work

|

Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536) |

| Theological work | |

| Era | Renaissance |

| Tradition or movement | |

| Main interests | Systematic theology |

| Notable ideas |

|

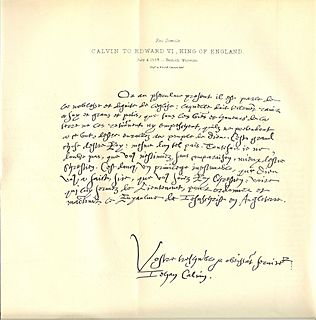

| Signature | |

John Calvin (1509–1564) was an important French theologian and reformer during the Protestant Reformation. He lived and worked in Geneva, Switzerland. Calvin was a main leader in developing a system of Christian beliefs known as Calvinism. This included ideas like predestination, which is the belief that God has already chosen who will be saved.

Calvin was a strong writer and often debated religious ideas. He wrote many books, including his most famous, Institutes of the Christian Religion. He also wrote comments on most books of the Bible.

Originally, Calvin studied to become a lawyer. Around 1530, he decided to leave the Roman Catholic Church. Because of religious conflicts and violence against Protestants in France, Calvin moved to Basel, Switzerland. There, in 1536, he published the first version of his Institutes.

Later that year, a reformer named William Farel asked Calvin to help with the Reformation in Geneva. Calvin became a preacher there. However, the city leaders didn't agree with all their ideas, so Calvin and Farel were asked to leave. Calvin then went to Strasbourg and led a church for French refugees. He continued to support the reform movement in Geneva. In 1541, he was invited back to lead the church in Geneva.

After returning, Calvin introduced new ways of church leadership and worship. He faced some opposition from powerful families in the city. During this time, a Spanish man named Michael Servetus came to Geneva. Servetus had different religious views that were seen as heretical by both Catholics and Protestants. Calvin reported him, and Servetus was executed by the city council for heresy. Later, with new supporters and elections, Calvin's opponents lost power. Calvin spent his last years helping the Reformation grow in Geneva and across Europe.

Contents

John Calvin's Early Life

Growing Up in France (1509–1535)

John Calvin was born as Jehan Cauvin on July 10, 1509, in Noyon, a town in France. He was one of three sons who lived past infancy. His mother died when he was young. His father, Gérard Cauvin, was a successful notary for the church. Gérard wanted his sons to become priests.

Young Calvin was very smart. By age 12, he worked for the bishop and received the tonsure, a haircut showing his dedication to the Church. He also got help from an important family, the Montmors. With their support, Calvin went to the Collège de la Marche in Paris. There, he learned Latin from a great teacher, Mathurin Cordier. After that, he studied philosophy at the Collège de Montaigu.

Around 1525, Calvin's father decided he should study law instead of becoming a priest. He thought Calvin could earn more money as a lawyer. So, Calvin enrolled at the University of Orléans. In 1529, he went to the University of Bourges. There, he became interested in Humanism, a movement that focused on classical studies. During his time in Bourges, Calvin learned Koine Greek, which was important for studying the New Testament.

Historians believe Calvin had a religious conversion around 1529 or 1530. This change led him to break away from the Roman Catholic Church.

By 1532, Calvin became a licensed lawyer. He also published his first book, a commentary on Seneca the Younger's De Clementia. In October 1533, Calvin returned to Paris. At this time, there were growing tensions between humanists and reformers, and the more traditional church leaders. A friend of Calvin's, Nicolas Cop, gave a speech calling for reform in the church. This speech was seen as heresy, and Cop had to flee to Basel. Calvin was also involved and had to hide for a year. He moved around, staying with friends in different towns.

In October 1534, Calvin was forced to leave France completely during the Affair of the Placards. In this event, reformers put up posters criticizing the Catholic mass. This led to violence against Protestants. In January 1535, Calvin joined Cop in Basel, Switzerland.

Calvin's Reform Work Begins

Starting in Geneva (1536–1538)

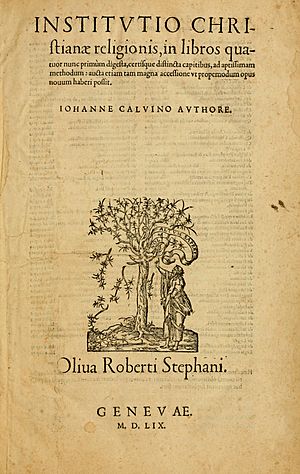

In March 1536, Calvin published the first edition of his major work, Institutes of the Christian Religion. This book was a defense of his faith and explained the beliefs of the reformers. It was also meant to be a basic guide for anyone interested in Christianity. This book was the first time Calvin's religious ideas were fully explained. He continued to update and publish new editions throughout his life.

Soon after publishing, Calvin traveled to Ferrara, Italy, and then returned to Paris. He realized there was no future for him in France due to religious persecution. In August, he headed for Strasbourg, a city that welcomed reformers. However, due to military conflicts, he had to take a detour through Geneva. Calvin only planned to stay one night. But William Farel, another French reformer in Geneva, begged him to stay and help with the church's reform.

Calvin agreed to stay. He was given the role of "reader," meaning he would give lectures on the Bible. In 1537, he was also chosen to be a "pastor." For the first time, Calvin, who was trained as a lawyer and theologian, took on duties like baptisms, weddings, and leading church services.

In late 1536, Farel wrote a statement of faith, and Calvin wrote ideas for how to organize the church in Geneva. In January 1537, they presented their "Articles on the Organization of the Church and its Worship at Geneva" to the city council. This document described how often to celebrate the Eucharist (Communion), how to use excommunication (excluding someone from the church), and how to use singing in worship. The council accepted the document.

However, Calvin and Farel's relationship with the council became difficult. The council was slow to make citizens agree to the new faith statement. Also, because Calvin and Farel were French, some council members questioned their loyalty as France sought an alliance with Geneva. A big argument happened when the city of Bern, an ally of Geneva, wanted all Swiss churches to use the same ceremonies. Bern suggested using unleavened bread for Communion. Calvin and Farel wanted to wait for a larger meeting to decide. But the council ordered them to use unleavened bread for Easter Communion. In protest, they refused to give Communion during the Easter service. This caused a riot. The next day, the council told Farel and Calvin to leave Geneva.

Calvin and Farel went to Bern and Zurich to explain their side. A meeting in Zurich blamed Calvin for not being understanding enough towards the people of Geneva. They asked Bern to help get the two ministers back. But the Geneva council refused. Farel went to lead a church in Neuchâtel. Calvin was invited to lead a church for French refugees in Strasbourg by Martin Bucer and Wolfgang Capito. Calvin first refused, but agreed when Bucer insisted. By September 1538, Calvin started his new role in Strasbourg, expecting to stay there permanently.

Leading a Church in Strasbourg (1538–1541)

In Strasbourg, Calvin preached and lectured daily, with two sermons on Sundays. Communion was held monthly, and singing psalms was encouraged. He also worked on the second edition of his Institutes. He changed its structure to present the main Bible teachings in a more organized way. The book grew from six to seventeen chapters.

He also wrote a book called Commentary on Romans, published in 1540. This book became a model for his later commentaries. It included his own Latin translation from Greek, explanations of the text, and teachings.

Calvin's friends encouraged him to marry. In August 1540, he married Idelette de Bure, a widow with two children.

Meanwhile, Geneva started to rethink its decision to expel Calvin. Church attendance had dropped, and the political situation changed. When a cardinal invited Geneva to return to the Catholic faith, the council needed someone to respond. They asked Calvin, and he agreed. His letter, Responsio ad Sadoletum, strongly defended Geneva's reforms.

In September 1540, the council decided to invite Calvin back. Calvin was at a religious conference in Worms when he heard the news. He was very hesitant, writing that he would "rather submit to death a hundred times." However, he also said he was ready to follow God's call. A plan was made for Calvin to return to Geneva. By mid-1541, Strasbourg agreed to let Calvin go to Geneva for six months. Calvin returned on September 13, 1541, with an official escort.

Reforming Geneva

Church Reforms (1541–1549)

To support Calvin's ideas, the Geneva council passed the Ordonnances ecclésiastiques (Church Ordinances) in November 1541. These rules set up four types of church roles:

- Pastors: To preach and lead sacraments.

- Doctors: To teach believers about faith.

- Elders: To help with church discipline.

- Deacons: To care for the poor and needy.

The ordinances also created the Consistory, a church court made up of elders and ministers. The city government could call people before this court, but the Consistory could only judge church matters, not civil ones. The court originally had the power to give sentences, with excommunication (being removed from the church) as the most serious. However, the government later decided that all sentencing would be done by the government.

In 1542, Calvin adapted a prayer book from Strasbourg and published La Forme des Prières et Chants Ecclésiastiques (The Form of Prayers and Church Hymns). Calvin believed music was powerful and should support Bible readings. He added many hymns, including the famous Old Hundredth.

That same year, Calvin published Catéchisme de l'Eglise de Genève (Catechism of the Church of Geneva). This book was a teaching guide for the church.

Historians discuss how much Geneva was a "theocracy" (a government ruled by religious leaders). While Calvin's beliefs called for separation of church and state, some historians point out the significant influence church leaders had on daily life.

During his time in Geneva, Calvin preached over two thousand sermons. He often preached twice on Sunday and three times during the week. His sermons lasted over an hour, and he usually didn't use notes. From 1549 onwards, a professional scribe recorded all his sermons. Calvin was known for preaching through entire books of the Bible in a series of sermons.

Very little is known about Calvin's personal life in Geneva. His house was owned by the city council. On July 28, 1542, his wife Idelette gave birth to a son, Jacques, but he died shortly after. Idelette became ill in 1545 and died on March 29, 1549. Calvin never married again. He remained friends with many people from his early life.

Challenges and Opposition (1546–1553)

Calvin faced strong opposition in Geneva. Around 1546, a group he called "libertines" (though they preferred "Spirituels" or "Patriots") began to challenge him. Calvin believed these people felt they were free from church and civil laws because of God's grace. This group included wealthy and powerful families in Geneva.

In January 1546, a man named Pierre Ameaux, who had argued with the Consistory before, attacked Calvin. He called him a "Picard" (a negative term for someone from Picardy, Calvin's home region) and accused him of false teachings. Ameaux was punished by the council and forced to publicly apologize. A few months later, Ami Perrin, the man who had helped bring Calvin back to Geneva, openly opposed him. Perrin's wife and father-in-law had also had problems with the Consistory. The church court noted that many important Genevans, including Perrin, had broken a law against dancing.

By 1547, most of the city's civil leaders (syndics) were against Calvin and the other French ministers. On June 27, a threatening letter was found at Calvin's pulpit in St. Pierre Cathedral. The council investigated and arrested Jacques Gruet, a member of Perrin's group. Under questioning, Gruet confessed to several crimes, including writing the threatening letter. A civil court sentenced Gruet to death, and he was beheaded on July 26. Calvin did not oppose this decision.

The "libertines" continued to oppose Calvin, insulting ministers and challenging the Consistory's authority. The council often went back and forth, sometimes supporting Calvin, sometimes not. When Perrin was elected as a main leader (first syndic) in February 1552, Calvin's power seemed to be at its lowest. Calvin felt defeated and asked the council to let him resign in July 1553. Even though the "libertines" controlled the council, they refused his request. They realized they could limit Calvin's power but couldn't banish him.

The Case of Michael Servetus (1553)

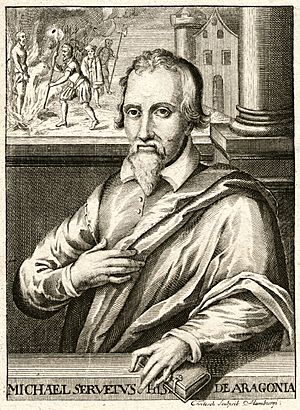

A major turning point happened when Michael Servetus, a Spanish scholar and a fugitive from religious authorities, arrived in Geneva on August 13, 1553. Servetus was on the run after publishing a book called The Restoration of Christianity (1553). In this book, he denied the Christian idea of original sin and had unusual views on the Trinity (God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit).

Years earlier, Servetus had argued with other reformers and was expelled from Basel and Strasbourg for his views. He had also published another book against the Trinity. When Calvin told the Inquisition in Spain about Servetus's book, an order was issued for Servetus's arrest.

Calvin and Servetus had exchanged letters since 1546, debating religious ideas. Calvin eventually became frustrated and refused to reply. He was especially angry when Servetus sent him a copy of Calvin's Institutes with many notes pointing out errors. When Servetus mentioned he might come to Geneva, Calvin wrote to a friend in 1546, saying that if Servetus came, he would not let him leave alive.

In 1553, Servetus published his book Christianismi Restitutio, rejecting the Trinity and predestination. Calvin's representative, Guillaume de Trie, sent letters to the French Inquisition about Servetus. Servetus was arrested in France, and his letters to Calvin were used as evidence of heresy. He managed to escape from prison, and the Catholic authorities sentenced him to death by slow burning in his absence.

On his way to Italy, Servetus stopped in Geneva, where he was recognized and arrested. Calvin's secretary wrote a list of accusations for the court. The trial was long, as the "libertines" tried to use Servetus to challenge Calvin. The council asked other Swiss cities for their opinions, which all agreed Servetus was a heretic. Servetus himself begged to stay in Geneva rather than be sent back to France.

On October 20, the council condemned Servetus as a heretic. The next day, he was sentenced to be burned at the stake, the same sentence he received in France. Some scholars say Calvin and other ministers asked for him to be beheaded instead, as burning was the only legal option. This request was denied. On October 27, Servetus was burned alive outside Geneva.

Securing the Reformation (1553–1555)

After Servetus's death, Calvin was seen as a defender of Christianity. However, his full victory over the "libertines" was still two years away. Calvin had always insisted that the Consistory should have the power of excommunication. During Servetus's trial, Philibert Berthelier, a "libertine," asked the council for permission to take communion, even though he had been excommunicated. Calvin argued that the council did not have the power to overturn the Consistory's decision.

The council decided to re-examine the Church Ordinances. On September 18, 1553, they voted to support Calvin, confirming that excommunication was the Consistory's power. Berthelier appealed to another assembly, which reversed the council's decision, saying the council should have the final say on excommunication. The ministers continued to protest, and the opinions of other Swiss churches were sought. The issue continued through 1554. Finally, on January 22, 1555, the council announced that the original Ordinances would be kept, and the Consistory would regain its official powers.

The "libertines" began to lose power after the February 1555 elections. Many French refugees had become citizens, and with their support, Calvin's supporters won most of the leadership positions. On May 16, the "libertines" protested in the streets, trying to burn down a house. The protest quickly ended. Perrin and other leaders were forced to flee the city. With Calvin's approval, other plotters who remained were found and executed. The opposition to Calvin's church leadership finally ended.

Final Years and Legacy (1555–1564)

In his final years, Calvin's authority was largely unchallenged. He became known internationally as a reformer, distinct from Martin Luther. Calvin was sad about the lack of unity among reformers. He worked with Heinrich Bullinger to sign an agreement between the Zurich and Geneva churches. He also supported the idea of a meeting of all evangelical churches, proposed by Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer, though it never happened.

Starting in 1555, Calvin welcomed Marian exiles (Protestants fleeing Catholic rule in England) to Geneva. Under Geneva's protection, they formed their own reformed church. These exiles, including John Knox, later took Calvin's ideas back to England and Scotland.

In Geneva, Calvin's main goal was to create a collège, a school for children. The school opened on June 5, 1559. It had two parts: a grammar school (the collège or schola privata) and an advanced school (the académie or schola publica). Calvin recruited Theodore Beza as its leader. Within five years, there were 1,200 students in the grammar school and 300 in the advanced school. The collège later became the Collège Calvin, a famous school in Geneva, and the académie became the University of Geneva.

Impact on France

Calvin cared deeply about reforming his home country, France. He worked hard to support the French Protestant movement, providing religious teachings, worship styles, and ideas for church and social structures. He also wrote many letters to French Protestants, encouraging them. Between 1555 and 1562, over 100 ministers were sent to France from Geneva.

Calvin's Last Illness

In late 1558, Calvin became ill with a fever. He forced himself to work to finish the final revision of his Institutes. This final edition was much larger than previous ones. Soon after recovering, he strained his voice while preaching, which caused a severe cough and burst a blood vessel in his lungs. His health steadily declined after that. He preached his final sermon on February 6, 1564.

On April 25, he made his will, leaving small amounts of money to his family and the collège. A few days later, the church ministers visited him, and he said his final goodbyes. He died on May 27, 1564, at age 54. His body was first displayed, but because so many people came to see it, reformers worried they would be accused of creating a new saint's cult. The next day, he was buried in an unmarked grave in the Cimetière des Rois. The exact location of his grave is unknown; a stone was added in the 19th century to mark a spot traditionally thought to be his.

Calvin's Theology

Calvin explained his religious ideas in his Bible commentaries, sermons, and other writings. But the most complete explanation of his views is in his main work, the Institutes of the Christian Religion. He wanted this book to be a summary of his Christian beliefs and to be read along with his commentaries. The different editions of this book show that his theology changed very little throughout his life. The first edition in 1536 had only six chapters. The final edition in 1559 had four books and eighty chapters. Each book was named after parts of the Apostles' Creed: Book 1 on God the Creator, Book 2 on Jesus as the Redeemer, Book 3 on receiving God's grace through the Holy Spirit, and Book 4 on the Church.

The Institutes begins by saying that human wisdom has two parts: knowing God and knowing ourselves. Calvin believed that we cannot know God just by looking at the world or by our own understanding. The only way to know God is by studying the Bible. He said, "For anyone to arrive at God the Creator he needs Scripture as his Guide and Teacher." He believed the Bible proves itself true. He defended the idea of the Trinity (God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) and argued against using images of God, saying they could lead to idolatry. Calvin famously said, "the human heart is a perpetual idol factory." He also wrote about God's plan, saying that God cares for and rules the world. Humans may not fully understand why God does certain things, but everything, good or bad, ultimately serves God's will.

The second book talks about original sin and the fall of humanity. Calvin believed that sin began with Adam and spread to all people. He taught that humans are so affected by sin that they are naturally drawn to evil. Therefore, fallen humanity needs to be saved through Christ. Calvin explained that God made a promise (a covenant) with Abraham in the Old Testament, promising the coming of Christ. So, the Old Covenant was not against Christ but was part of God's ongoing promise. Calvin then described the New Covenant through Christ's suffering and return to judge. He believed that Christ's obedience to God removed the separation between humanity and God.

In the third book, Calvin explained how people become spiritually connected with Christ. He defined faith as a strong and certain knowledge of God in Christ. The immediate results of faith are repentance (turning away from sin) and forgiveness of sins. This leads to spiritual renewal, which brings believers closer to the holiness they had before Adam sinned. Complete perfection is not possible in this life, and believers should expect a continuous fight against sin. Several chapters discuss justification by faith alone. He defined justification as "the acceptance by which God regards us as righteous whom he has received into grace." This means God is fully in charge of salvation, and people play no part in earning it. Near the end of the book, Calvin explained and defended predestination, the idea that God has chosen some people for eternal life and others for eternal damnation. Calvin called this a "dreadful decree."

The final book describes what Calvin believed was the true Church, its leaders, authority, and sacraments. He disagreed with the Pope's claim to be the highest authority and denied that reformers were causing a split in the church. For Calvin, the Church was the body of believers with Christ as its head. He believed there was only one "catholic" or "universal" Church. He argued that reformers "had to leave them in order that we might come to Christ." The Church's ministers, based on a passage from Ephesians, included apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors, and doctors. Calvin saw the first three as temporary roles from the New Testament era. The last two roles were set up in the church in Geneva. While Calvin respected the work of church councils, he believed they were subject to God's Word in the Bible. He also thought that civil and church authorities should be separate and not interfere with each other.

Calvin defined a sacrament as an earthly sign connected to a promise from God. He accepted only two sacraments as valid under the new covenant: baptism and the Lord's Supper (Communion). He rejected the Catholic belief that the bread and wine in Communion literally become the body and blood of Christ. He also disagreed with Luther's view that Christ was "in, with and under" the elements. Calvin's own view was similar to Zwingli's symbolic view, but not exactly the same. Calvin believed that through the Holy Spirit, faith was strengthened by the sacrament. He described it as "a secret too sublime for my mind to understand or words to express. I experience it rather than understand it."

Calvin and Jewish People

Scholars have different opinions on Calvin's views about Jewish people and Judaism. Some say he was less antisemitic than other major reformers like Martin Luther. Others argue he was still part of the antisemitic views common at the time. Scholars agree it's important to separate Calvin's views on the Jewish people in the Bible from his views on Jewish people living in his own time. In his theology, Calvin saw God's covenant with Israel and the New Covenant as connected. He said, "all the children of the promise, reborn of God, who have obeyed the commands by faith working through love, have belonged to the New Covenant since the world began." However, he also believed that Jewish people were rejected and needed to accept Jesus to rejoin the covenant.

Most of Calvin's comments about Jewish people in his time were part of religious debates. For example, Calvin once wrote, "I have had much conversation with many Jews: I have never seen either a drop of piety or a grain of truth or ingenuousness—nay, I have never found common sense in any Jew." In this way, his views were similar to other Protestant and Catholic theologians of his day. In one of his writings, Response to Questions and Objections of a Certain Jew, he argued that Jewish people misunderstood their own scriptures because they missed the connection between the Old and New Testaments.

Calvin's Political Ideas

Calvin's political ideas aimed to protect the rights and freedoms of ordinary people. He believed the Bible didn't give a specific blueprint for government, but he preferred a mix of democracy and aristocracy (rule by a small group of leaders). He liked the benefits of democracy. To prevent political power from being misused, Calvin suggested dividing it among different groups, like leaders or magistrates, in a system of checks and balances.

Calvin also taught that if rulers go against God, they lose their divine right to rule and should be removed. He believed that the government and the church should be separate but should work together for the good of the people. Christian leaders should make sure the church can do its work freely. In extreme cases, leaders might need to remove or execute dangerous heretics, but no one should be forced to become a Protestant.

Calvin thought that farming and traditional crafts were normal human activities. He was more open to trade and finance than Luther, but both strongly opposed charging very high interest rates (usury). Calvin allowed charging modest interest on loans. Like other reformers, Calvin saw work as a way for believers to show thanks to God for their salvation and to serve their neighbors. Everyone was expected to work; laziness and begging were not accepted. The idea that economic success showed God's favor was not a main part of Calvin's thinking. This idea became more important in later forms of Calvinism and influenced Max Weber's theory about the rise of capitalism.

Selected Works by Calvin

Calvin's first published work was a commentary on Seneca the Younger's De Clementia in 1532. This showed he was a humanist, like Erasmus, with a good understanding of classical studies. His first religious work, the Psychopannychia, tried to argue against the idea of "soul sleep" (that the soul sleeps between death and resurrection), which was taught by the Anabaptists.

Calvin wrote commentaries on most books of the Bible. His first commentary on Romans was published in 1540. He aimed to write commentaries on the entire New Testament. He published commentaries on all the Pauline epistles and revised his Romans commentary. He then focused on the general epistles, dedicating them to Edward VI of England. By 1555, he finished his work on the New Testament, including the Acts and the Gospels (he only skipped the short second and third Epistles of John and the Book of Revelation). For the Old Testament, he wrote commentaries on Isaiah, the Pentateuch, the Psalms, and Joshua. The material for these commentaries often came from his lectures to students and ministers.

Calvin also wrote many letters and other writings. After his Responsio ad Sadoletum, he wrote an open letter to Charles V in 1543, defending the reformed faith. This was followed by an open letter to Pope Paul III in 1544, criticizing the Pope for not allowing reconciliation with reformers. When the Pope opened the Council of Trent and issued decrees against reformers, Calvin wrote a response in 1547. When Charles tried to find a compromise, Calvin wrote a treatise in 1549, explaining the doctrines that should be upheld, including justification by faith.

Calvin provided many important documents for reformed churches, including guides on catechism (religious instruction), worship, and church governance. He also wrote several statements of faith to unite the churches. In 1559, he drafted the French confession of faith, the Gallic Confession, which was accepted with few changes. The Belgic Confession of 1561, a Dutch confession of faith, was partly based on the Gallic Confession.

Calvin's Lasting Impact

After Calvin's death and that of his successor, Beza, the Geneva city council slowly gained more control over areas of life that were previously managed by the church. This led to a gradual decrease in the church's influence. Even the Geneva académie was surpassed by universities in Leiden and Heidelberg, which became new centers for Calvin's ideas, first called "Calvinism" in 1552. By 1585, Geneva, once the heart of the reform movement, became more of a symbol.

Calvin had always warned against treating him as an "idol" or Geneva as a new "Jerusalem." He encouraged people to adapt to their local situations. Even when he disagreed with Lutherans, he still believed they were part of the true Church. Calvin's understanding of adapting to local conditions became a key feature of the Reformation as it spread across Europe.

Because of Calvin's missionary work in France, his reform program eventually reached the French-speaking parts of the Netherlands. Calvinism was adopted in the Electorate of the Palatinate under Frederick III, which led to the creation of the Heidelberg Catechism in 1563. This and the Belgic Confession became official standards for the Dutch Reformed Church in 1571. Several important religious leaders who were Calvinist or supported Calvinism settled in England (Martin Bucer, Peter Martyr, and Jan Laski) and Scotland (John Knox). During the English Civil War, the Calvinistic Puritans created the Westminster Confession, which became the standard for Presbyterians in English-speaking countries.

The Ottoman Empire did not force Muslim conversion on the western lands they conquered. Because of this, reformed ideas were quickly adopted in the two-thirds of Hungary that the Ottomans controlled. A Reformed meeting was held in 1567 in Debrecen, a main center of Hungarian Calvinism. There, the Second Helvetic Confession was adopted as the official confession of Hungarian Calvinists.

After establishing itself in Europe, the movement continued to spread to other parts of the world, including North America, South Africa, and Korea.

Calvin did not live to see his work grow into an international movement. However, his death allowed his ideas to spread beyond Geneva and establish their own unique character.

Calvin is recognized as a Renewer of the Church in Lutheran churches and is remembered in the Church of England on May 26.

See also

In Spanish: Juan Calvino para niños

In Spanish: Juan Calvino para niños

- Theology of John Calvin

- History of Protestantism

- Swiss Reformation

- Theodore Beza

Archive sources

- The State Archives of Neuchâtel preserve the autograph correspondence sent by John Calvin to other reformers

- 1PAST, Fonds: Archives de la société des pasteurs et ministres neuchâtelois, Series: Lettres des Réformateurs. Archives de l'État de Neuchâtel.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |