Columbus's letter on the first voyage facts for kids

A letter written by Christopher Columbus on February 15, 1493, was the first document to share the news of his first trip across the Atlantic. This journey started in 1492 and led him to the Americas. Columbus supposedly wrote the letter while on his ship, the Niña, as he was sailing back home. He added a short update when he arrived in Lisbon, Portugal, on March 4, 1493. From Lisbon, he likely sent two copies of his letter to the Spanish rulers.

This letter was super important for spreading the news of Columbus's voyage across Europe. Soon after he arrived in Spain, printed copies of the letter started appearing. A Spanish version was printed in Barcelona by early April 1493. A Latin translation was published in Rome about a month later. The Latin version quickly spread and was reprinted in many other cities like Basel, Paris, and Antwerp, all within the first year of his return.

In his letter, Christopher Columbus said he had found and claimed several islands near the Indian Ocean in Asia. Columbus didn't know he had actually landed on a new continent. He described the islands, especially Hispaniola and Cuba, making them sound bigger and richer than they were. He also suggested that mainland China was probably close by. He briefly described the native Arawaks, calling them "Indians". He said they were peaceful and easy to get along with, and that they could be converted to Catholicism.

However, the letter also mentioned local stories about a fierce tribe of "monsters" who ate people. These were probably the Caribs. Columbus himself didn't believe these stories and thought they were just myths. The letter didn't give many details about the ocean journey itself. It also hid the fact that his main ship, the Santa María, was lost. Columbus claimed he left it behind with some settlers in a fort he built at La Navidad in Hispaniola. In the letter, Columbus asked the Catholic monarchs to pay for a second, bigger trip to the Indies. He promised to bring back huge amounts of wealth.

A slightly different handwritten version of Columbus's letter was found in 1985. It was part of a collection called the Libro Copiador. This discovery has changed some of what historians thought about Columbus's letter.

In 2017, the two earliest published copies of Columbus's letter about his first voyage on the Niña were given to the University of Miami library in Coral Gables, Florida. They are kept there today.

Contents

Why Columbus Wrote the Letter

Christopher Columbus was a captain from Genoa who worked for the Crown of Castile in Spain. He started his first voyage in August 1492. His goal was to reach the East Indies by sailing west across the Atlantic Ocean. As many know, instead of reaching Asia, Columbus found the Caribbean islands in the Americas.

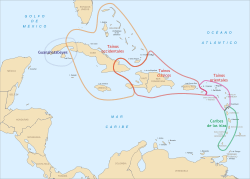

Even though he was in a new place, Columbus was sure he had found the edges of Asia. He began his trip back to Spain on January 15, 1493, on his ship, the Niña. His travel diary says that on February 14, Columbus got caught in a storm near the Azores islands. Because his ship was in bad shape, he had to stop in Lisbon (Portugal) on March 4, 1493. Columbus finally arrived in Palos de la Frontera, Spain, eleven days later, on March 15, 1493.

During his journey back, while still on the ship, Columbus wrote a letter. It told about what happened on his trip and announced his discovery of the "islands of the Indies." In an update added while he was waiting in Lisbon, Columbus said he sent at least two copies of the letter to the Spanish court. One copy went to the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile. The second copy went to Luis de Santángel, an important official from Aragon who was a main supporter and helped pay for Columbus's trip.

How the Letter Spread

Copies of Columbus's letter somehow reached publishers. Printed versions of his letter started appearing all over Europe just weeks after Columbus returned to Spain. A Spanish version was printed in Barcelona in late March or early April 1493. This was likely based on the letter he sent to Luis de Santángel. A Latin translation was printed in Rome about a month later. This one was addressed to Gabriel Sanchez.

Within the first year of Columbus's return, eight more Latin versions were printed in different European cities. Two were printed in Basel, three in Paris, two more in Rome, and one in Antwerp. By June 1493, a poet had even translated the letter into Italian verse. That version was printed many times over the next few years. A German translation came out in 1497. The quick spread of Columbus's letter was possible because of the printing press. This new invention had only recently become widely used.

Columbus's letter, especially the Latin version, shaped how people in Europe first thought about the newly found lands. Before Columbus's own travel diary was published in the 1800s, this letter was the only direct account from him about his first voyage in 1492. It's thought that between 1493 and 1500, about 3,000 copies of Columbus's letter were published. Half of these were in Italy, making it a very popular book for its time. In comparison, Columbus's letters from his second (1495) and fourth (1505) voyages were only printed once, probably with fewer than 200 copies each.

The original handwritten letters from Columbus have never been found. Only the printed versions in Spanish and Latin are known. However, a third version of the letter was found in 1985. It was in a 16th-century collection of handwritten papers called the Libro Copiador. This handwritten version is different in several important ways from the printed ones. Even though its truthfulness is still being checked, many believe the Copiador version is closer to what Columbus originally wrote.

What the Letter Said

The printed Latin versions of the letter usually had a title like "Letter of Columbus, about the islands of India beyond the Ganges recently discovered." "India beyond the Ganges" was an old term for Southeast Asia. Columbus didn't describe the journey itself. He only said he traveled for thirty-three days and arrived at the islands of "the Indies." He wrote that he "took possession for our Highnesses, with proclaiming heralds and flying royal standards, and no one objecting." He said the islands were home to "Indians."

In the printed letters, Columbus said he gave new names to six of the islands. Four are in the modern Bahamas:

- (1) Sant Salvador (also called Guanaham or Guanahanin; today known as Guanahani)

- (2) Santa Maria de Concepcion

- (3) Ferrandina (today Fernandina)

- (4) la isla Bella (today La Isabela)

He also named (5) La Isla Juana (today Cuba) and (6) La Spañola (today Hispaniola). In the letter, Columbus said he thought Juana was part of the mainland of Cathay (an old name for China). However, he also admitted that some of the native people told him Juana was an island. Later in the letter, Columbus said the islands were at a latitude of 26°N, which is north of their actual location.

Columbus wrote that he sailed along the northern coast of Juana (Cuba) for a while. He was looking for cities and rulers, but he only found small villages "without any sort of government." He noticed that the native people usually ran away when he approached. Since this didn't lead anywhere, he decided to turn back and head southeast. He eventually saw the large island of Hispaniola and explored its northern coast. Columbus made these lands sound much bigger than they were. He claimed Juana was larger than Great Britain and Hispaniola was bigger than the entire Iberian peninsula (Spain and Portugal).

In his letter, Columbus seemed to want to show that the islands of the Indies would be good places for future colonization. His descriptions of nature in his letters highlighted the rivers, forests, pastures, and fields. He said they were "very suitable for planting and cultivating, for raising all sorts of livestock herds and erecting towns and farms." He also stated that Hispaniola "abounds in many spices, and great mines of gold, and other metals." He thought Hispaniola, with its lush land and water, was better for settlement than mountainous Cuba.

Columbus described the native people of the Indies islands as simple, innocent, and not thinking clearly ("like beasts"). He said they were not a threat. He wrote that they mostly went around naked, didn't have iron or weapons, and were naturally scared and shy. He even called them "excessively cowardly."

Columbus said that when the natives were convinced to interact, they were very generous and trusting. They were willing to trade large amounts of valuable gold and cotton for useless glass trinkets, broken pottery, and even shoelace tips. In the printed letters, Columbus mentioned that he tried to stop his sailors from taking advantage of the natives' trusting nature. He even gave valuable things like cloth to the natives as gifts. He did this so they would be friendly and "might be made Christians and incline full of love and service towards Our Highnesses and all the Castilian nation."

Columbus specifically noted that the natives did not have an organized religion. He said they didn't even worship idols. He claimed the natives believed the Spanish and their ships had "come down from heaven." Columbus observed that the natives on different islands seemed to speak the same language (the Arawaks in the area all spoke Taíno). He thought this would make it easier to convert them "to the holy religion of Christ, to which in truth, as far as I can perceive, they are very ready and favorably inclined."

Columbus might have worried that his description would make it seem like the natives couldn't do useful work. So, he added that the Indians were "not slow or unskilled, but of excellent and acute understanding." He also noted that the "women appear to work more than the men."

Columbus's physical descriptions were brief. He only noted that the natives had straight hair and "nor are they black like those in Guinea." They usually went around naked, though sometimes they wore a small cotton loincloth. They often carried a hollow cane, which they used for both farming and fighting. They ate their food "with many spices which are far too hot." Columbus claimed the Indians practiced having only one wife, "except for the rulers and kings" who could have up to twenty wives. He admitted he wasn't sure if they understood private property. In a more detailed part, Columbus described the Indian oar-driven canoe. This is the first known time this word, from the Taíno language, appeared in writing. Columbus compared the Indian canoe to a small European ship called a fusta.

Towards the end of the letter, Columbus mentioned that local Indians told him about the possible existence of people who ate human flesh, whom he called "monsters." This was likely a reference to the Caribs from the Leeward Islands. Columbus said the monsters were reported to have long hair and be very fierce. Columbus himself hadn't seen them. But he said local Indians claimed the monsters had many canoes and sailed from island to island, raiding everywhere. However, Columbus said he didn't believe these "monsters" existed. He thought it was probably just a local Indian story about some distant seafaring tribe who were probably not very different from themselves.

Columbus connected the monster story to another local legend about a tribe of female warriors. These women were said to live on the island of "Matinino" east of Hispaniola. Columbus thought the canoe-borne monsters were just the "husbands" of these warrior women. He believed they visited the island sometimes for mating. The island of women was reportedly rich in copper, which the warrior-women used to make weapons and shields.

To make sure his readers didn't get too worried, Columbus ended with a more hopeful report. He said the local Indians of Hispaniola also told him about a very large island nearby that "abounds in countless gold." In the printed letters, Columbus claimed he was bringing back some of the "bald-headed" people from this gold island with him. Earlier in the letter, Columbus had also spoken of the land of "Avan" in the western parts of Juana. There, men were said to be "born with tails." This was probably a reference to the Guanajatabey people of western Cuba.

The Libro Copiador version of the letter has more native names for islands than the printed versions. For example, in the Copiador letter, Columbus noted that the island of "monsters" was called "Caribo." He also explained how the warrior-women of Matinino sent their male children there to be raised. It also mentioned an island called "Borinque" (Puerto Rico), which wasn't in the printed versions. Natives reported it was between Hispaniola and Caribo. The Copiador letter noted that Juana was called "Cuba" by the natives. He also gave more details about the gold island. He said it was "larger than Juana" and on the other side of it, "which they call Jamaica," where "all the people have no hair and there is gold without measure." In the Copiador letter, Columbus suggested he was bringing normal (full-haired) Indians back to Spain who had been to Jamaica. They would report more about it, instead of bringing the island's own bald-headed people, as claimed in the printed letters.

Columbus also described some of his own actions in the letters. He noted that he ordered the building of the fort of La Navidad on Hispaniola. He left some Spanish settlers and traders there. Columbus reported he also left behind a caravel. This was clearly to hide the loss of his main ship, the Santa María. He reported that La Navidad was near gold mines and was a good trading post for future business with the Great Khan on the mainland. He spoke of a local king near Navidad whom he befriended and treated like a brother. This was almost certainly Guacanagaríx, a leader of the Marién area.

At the end of his printed letter, Columbus promised that if the Catholic Monarchs supported his plan to return with a larger fleet, he would bring back a lot of gold, spices, cotton, mastic gum, aloe, slaves, and possibly rhubarb and cinnamon.

Columbus ended the letter by urging the King and Queen, the Church, and the people of Spain to thank God. He said God allowed him to find so many people, who were previously lost, ready to become Christians and achieve eternal salvation. He also urged them to give thanks in advance for all the riches found in the Indies. These riches would soon be available to Castile and the rest of Christendom.

The Copiador version, but not the printed Spanish or Latin versions, also included a strange idea. Columbus suggested the monarchs should use the wealth from the Indies to pay for a new crusade to conquer Jerusalem. Columbus himself offered to pay for a large army of ten thousand cavalry and one hundred thousand foot soldiers for this goal.

The way the letter ended was different in various editions. The printed Spanish letter was dated aboard the caravel "on the Canary Islands" on February 15, 1493. It was signed simply "El Almirante" (The Admiral). The printed Latin editions were signed "Cristoforus Colom, oceanee classis prefectus" (Prefect of the Ocean fleet). However, it's doubtful Columbus actually signed the original letter this way. According to the Capitulations of Santa Fe agreed before he left (April 1492), Christopher Columbus was not allowed to use the title of "Admiral of the Ocean Sea" unless his voyage was successful. It would have been very bold for Columbus to sign his name that way in February or March, before his success was confirmed by the royal court. Columbus only officially got his title on March 30, 1493. That's when the Catholic Monarchs, after receiving his letter, called him "our Admiral of the Ocean Sea and Vice-Roy and Governor of the islands which have been discovered in the Indies." This suggests the signature in the printed editions was added by editors or printers, not by Columbus in his original letter.

The Letter's Journey and Copies

No original handwritten copy of Columbus's letter exists today. Historians have had to use clues from the printed versions to figure out the letter's history. Many of these printed versions didn't have a date or location.

It's believed that Columbus wrote the first letter in Spanish. Because of this, historians generally agree that the Barcelona edition was probably the first to be published. It didn't have a date or printer's name and looked like it was printed quickly. This suggests it was very close to the original handwritten letter. At the end of the Barcelona edition, there's a note that says:

-

- "This letter was sent by Columbus to the Escrivano de Racion. Of the islands found in the Indies, it contains (or was contained in?) another (letter) for their Highnesses."

This note suggests that Columbus sent two letters. One went to the Escrivano de Ración, Luis de Santángel, and another to the Catholic Monarchs.

In the printed Spanish letter, the update at the end is dated March 14, not March 4. This might just be a printing mistake. The letter to the monarchs in the Libro Copiador has the correct date for the update, March 4, 1493.

How the Letters Were Sent

Columbus's son, Ferdinand Columbus, and Bartolomé de las Casas both said that Columbus wrote two letters to the Catholic Monarchs during a storm near the Azores on February 14. He sealed them in waterproof barrels. One was thrown overboard, and the other was tied to the back of the ship. The idea was that if the ships sank, the letters would float to land. It's very unlikely the letters were sent this way. The barrels were probably brought back when the storm ended. The update at the end of the letter confirms they were sent later. It's also unlikely Columbus started writing the long letter in the middle of a storm; he probably wrote most of it before the storm began on February 12 and rushed to finish when the storm hit.

There's some debate about whether Christopher Columbus sent the letters directly from Lisbon. He docked there on March 4, 1493. Or, did he wait until he reached Spain, sending the letters only after arriving at Palos de la Frontera on March 15, 1493?

It's very likely, though not certain, that Columbus sent the letter from Lisbon to the Spanish court, probably by a messenger. Columbus's diary says that when he docked in Lisbon, Bartholomew Dias (on behalf of King John II of Portugal) demanded that Columbus give his report to him. Columbus strongly refused, saying his report was only for the Spanish monarchs. Columbus probably knew time was important. It was common for royal and business agents to meet and question returning sailors at the docks. So, the Portuguese king would likely get the information he wanted soon enough. Once he knew where Columbus's discovered islands were, John II might try to claim them for Portugal. So, Columbus realized the Spanish court needed to know about his voyage as soon as possible. If Columbus had waited until he reached Palos to send his letter, it might have been too late for the Spanish monarchs to stop any Portuguese actions. The earliest Spanish news report, saying Columbus "had arrived in Lisbon and found all that he went to seek," was in a letter by Luis de la Cerda y de la Vega, Duke of Medinaceli, in Madrid, dated March 19, 1493.

Columbus might have put some false information in his letter because he feared Portuguese agents might stop the messenger from Lisbon. For example, Columbus claimed he wrote the letter on a caravel while he was near the Canary Islands (instead of the Azores). This was probably to hide that he had been sailing in Portuguese waters. In the letter, Columbus also said the islands were at 26°N latitude. This is quite north of their actual location. He was probably trying to place them above the latitude line set by the Treaty of Alcáçovas of 1479. This treaty marked the boundary of the Portuguese crown's exclusive areas. He didn't quite make it, as the treaty line was at the Canary Islands latitude, about 27°50'. He didn't give details about his direction or whether the waters were shallow or deep. Columbus's letters "say much and reveal nothing." Also, he was unclear about how long the trip took, claiming it was "thirty-three days." This is roughly correct if measured from the Canaries, but it was seventy-one days since he left Spain. Columbus's letter left this unclear. Finally, his strong statement that he officially "took possession" of the islands for the Catholic monarchs, and left men (and a ship) at La Navidad, may have been emphasized to prevent any Portuguese claims.

Who Received the Letters

The Spanish letter from Columbus was clearly sent to the Escribano de Ración. At that time, this was Luis de Santángel. The Escribano de Ración was an official position of the Crown of Aragon. This person was the main accountant for the king's household expenses, like a finance minister to Ferdinand II of Aragon.

It's not surprising that Columbus chose Santangel as the first person to get the news. Santangel was the one who convinced Queen Isabella to support Columbus's voyage eight months earlier. In fact, Santangel arranged much of the funding for the Castilian crown, often from his own money, to allow the monarchs to pay for it. Since Santangel had a lot riding on the success of this trip, perhaps more than anyone else, it was natural for Columbus to send his first letter to him. Also, as the letter showed, Columbus wanted more money to return with an even larger fleet to the Indies as soon as possible. So, it would be helpful to contact Santangel right away so he could start planning for a second voyage.

The story of the second copy of the letter, supposedly sent to the Catholic Monarchs, is more complex. The word "contain" in the note at the end of the Spanish Letter to Santangel makes it unclear which letter was inside which. Some historians think the letters to the Monarchs and to Santangel were sent separately, maybe even on different days (March 4 and 14). Others suggest Santangel was supposed to personally deliver the letter to the monarchs. Still others believe it was the other way around: that the letter to Santangel was first given to the monarchs for royal approval before being sent to Santangel for printing. The Catholic monarchs' reply to Columbus, dated March 30, 1493, confirmed they received the letter but didn't say how it was delivered.

For a long time, historians believed that the printed Spanish versions, which didn't name a recipient other than "Señor," were based on the copy of the letter Columbus sent to Luis de Santangel. But they thought the Latin version printed in Rome (and later Basel, Paris, etc.) was a translated copy of the letter Columbus sent to the Catholic Monarchs.

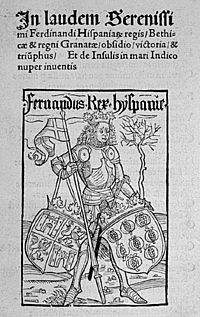

The printed Spanish and Latin versions are almost the same, with only very small differences. Most of these differences are due to the printers. The Latin version, in particular, leaves out the update and note about the Escribano. It adds a beginning and end that aren't in the Spanish versions, which give some clues about where it came from. The earliest Latin version, which doesn't have a date or printer's name, says the letter was sent to "Raphael Sanxis" (thought to be Gabriel Sanchez, the treasurer of the Crown of Aragon). It also has a greeting at the beginning for the Catholic king Ferdinand II of Aragon. The beginning notes that the translation into Latin was done by the notary Leander de Cosco and finished on April 29, 1493. The Latin versions also have an ending with a short poem praising Ferdinand II, written by Leonardus de Corbaria, Bishop of Monte Peloso.

For much of the last century, many historians thought these notes meant the Latin version was a translated copy of the letter Columbus sent to the Catholic monarchs. The common story was that after Columbus's original Spanish letter was read aloud at court, Ferdinand II (or his treasurer, Gabriel Sanchez) asked the notary Leander de Cosco to translate it into Latin. A copy was then sent to Naples, which was part of the Crown of Aragon at the time. There, Bishop Leonardus got hold of it. The bishop then took it to Rome, probably to tell Pope Alexander VI what it said. At that time, the pope was trying to settle arguments between Portugal and Spain over Columbus's discoveries. The pope's first official statement, Inter caetera, was issued on May 3, 1493. It's possible Bishop Leander wanted to use Columbus's letter to influence this process. While in Rome, Bishop Leonardus arranged for the letter to be published by the Roman printer Stephanus Plannck. This was possibly to help make the Spanish case more popular. The letter being reprinted in Basel, Paris, and Antwerp within a few months suggests that copies of the Roman edition traveled along normal trade routes into Central Europe. Merchants interested in this news probably carried them.

The discovery in 1985 of a handwritten copybook, known as the Libro Copiador, changed this history. It contained a copy of Columbus's letter addressed to the Catholic Monarchs. The Copiador version has some very clear differences from the printed versions. It is now increasingly believed that the Latin version printed in Rome is actually a translation of the letter to Santangel. And that the letter to the Monarchs was never translated or printed. This means that all the printed versions, both Spanish and Latin, came from the same Spanish letter to Luis de Santangel. In this view, the mention of "Raphael Sanxis" added by the Roman printer is seen as a simple mistake. It probably came from confusion in Italy about who was the "Escribano de Racion" of Aragon at the time. The bishop or printer might have mistakenly thought it was Gabriel Sanchez and not Luis de Santangel.

However, some historians believe that Columbus sent three different letters: one to the Catholic Monarchs (the handwritten copy), another to Luis de Santangel (the source of the printed Spanish versions), and a third to Gabriel Sanchez (the source of the Latin versions). This means that the Santangel and Sanchez letters, though almost identical, are still separate. But this raises the question of why Columbus would have sent a separate letter to Gabriel Sanchez, who he wasn't close to. Sanchez also wasn't very involved in the Indies project, nor was he more influential in court than Santangel or others Columbus might have written to.

It has been suggested in recent years that the printed letter might not have been written entirely by Columbus. Instead, it might have been edited by a court official, probably Luis de Santangel. This idea is supported by the discovery of the Libro Copiador. The text in the printed Spanish and Latin versions is much cleaner and more organized than Columbus's rambling writing in the letter to the monarchs found in the Libro Copiador. The printed versions leave out almost all of Columbus's personal complaints. These include issues over ship choices, how he was treated in the royal court, or the disobedience of "one from Palos" (Martín Alonso Pinzón). They also omit Columbus's strange call for a crusade in the Holy Land. The removal of these "distracting" points strongly suggests that someone else edited the printed versions. This editor was probably a royal official, as these points could have made the crown look bad or undignified.

This suggests that the printing of the Columbus letter, if not directly ordered by the king and queen, probably had their knowledge and approval. Its purpose might have been to make the Spanish case against Portuguese claims more popular. As mentioned before, these claims were being strongly discussed in the papal court throughout 1493–94. If so, it's very possible that Luis de Santangel was that royal official. He might have edited the content and overseen the printing in Spain. And it was Santangel who sent a copy of the edited letter to Gabriel Sanchez, who then shared it with his contacts in Italy to be translated into Latin and Italian and printed there. The unusual details of the printed versions, like "Catalanisms" in the spelling and the omission of Isabella, suggest that this entire editing, printing, and sharing process was handled from the start by officials from Aragon, like Santangel and Sanchez, rather than Castilians.

The small number of Spanish editions and their later disappearance would fit this idea. To influence public opinion in Europe, especially the Church and the Pope, a Spanish version wasn't as useful as a Latin one. So, there was no reason to keep printing the Spanish edition once the Latin one was available. In fact, there was no point in reprinting the Latin editions either, once the Treaty of Tordesillas was signed in June 1494. Thus, Columbus's letter is an early example of how the new printing press was used by the government for propaganda.

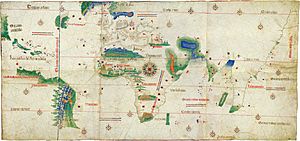

Settling the Claims

Christopher Columbus was probably right to send the letter from Lisbon. Soon after, King John II of Portugal began to prepare a fleet to take the discovered islands for the Kingdom of Portugal. The Portuguese king suspected, correctly, that the islands Columbus found were south of the latitude line of the Canary Islands (about 27°50'). This line was the boundary set by the 1479 Treaty of Alcáçovas for Portugal's exclusive area. This was confirmed by the papal bull Aeterni regis in 1481.

Urgent reports about Portugal's preparations were sent to the Spanish court by the Duke of Medina-Sidonia. Ferdinand II sent his own messenger, Lope de Herrera, to Lisbon. He asked the Portuguese to immediately stop any trips to the west Indies until the location of those islands was decided. If polite words didn't work, he was to threaten them. Even before Herrera arrived, John II had sent his own messenger, Ruy de Sande, to the Spanish court. He reminded the Spanish monarchs that their sailors were not allowed to sail south of the Canaries latitude. He suggested all trips to the west be stopped. Columbus, of course, was busy getting ready for his second journey.

Pope Alexander VI, who was from Aragon and a friend of Ferdinand II, was brought in to settle the rights to the islands and decide the limits of the competing claims. His first official statement on the matter, Inter caetera, dated May 3, 1493, was not clear. The pope gave the Crown of Castile "all lands discovered by their envoys" (meaning Columbus). This was as long as no other Christian owner possessed them, which Columbus's letter confirmed. On the other hand, the Pope also protected Portuguese claims by confirming their earlier treaties and statements. So, at first, the pope left the matter undecided until the islands' actual location was determined.

It was soon realized that the islands probably lay south of the latitude boundary. So, a little later, Pope Alexander VI issued a second statement, Eximiae devotionis (officially dated May 3, but written around July 1493). This tried to fix the problem by subtly suggesting the Portuguese treaty applied to "Africa," and noticeably leaving out any mention of the Indies. In his third attempt, in another statement also called Inter caetera, written in the summer and dated back to May 4, 1493, the Pope again confirmed the Spanish claim on the Indies more clearly. He drew a longitude line of demarcation, giving all lands 100 leagues west of Cape Verde to the Crown of Castile.

It's not clear exactly how the printed versions of Columbus's letter influenced this process. The letter reported the islands were at 26°N, which is just south of the Canary latitude. So, the letter almost helped Portugal. It forced the pope to try to confirm Spanish ownership without breaking earlier treaties. However, the increasing strength of the pope's statements over the summer, when the letter was widely circulated, suggests the Spanish case was ultimately helped, not hurt, by the letter. Small details about latitude degrees seemed unimportant compared to the excitement of the new discoveries revealed in the letters. While the Portuguese tried to make Columbus seem like just another Spanish intruder, illegally trading in their waters, the letters presented him as a great discoverer of new lands and new peoples. The idea of new people ready to become Christians, which the letters emphasized, and a Spanish crown eager to pay for that effort, must have changed many opinions.

Frustrated by the pope, John II decided to deal directly with the Spanish. The Portuguese messengers Pero Diaz and Ruy de Pina arrived in Barcelona in August. They asked that all expeditions be stopped until the islands' exact location was determined. Eager to act first, Ferdinand II stalled for time. He hoped he could get Columbus to start his second voyage to the Indies before any stops were agreed upon. As the king wrote to Columbus (September 5, 1493), the Portuguese messengers had no idea where the islands were actually located.

On September 24, 1493, Christopher Columbus left on his second voyage to the west Indies with a huge new fleet. The Pope added another statement on the matter, Dudum siquidum, written in December but officially dated September 26, 1493. In this, he went further than before. He gave Spain claim over any and all lands discovered by her messengers sailing west, no matter where those lands were in the world. Dudum Siquidum was issued with a second voyage in mind. If Columbus did reach China, India, or even Africa on this trip, the lands discovered would come under Spain's exclusive control.

Later talks between Portugal and Spain happened while Columbus was away. They ended with the Treaty of Tordesillas. This treaty divided the world between Spanish and Portuguese areas of control. The dividing line was 370 leagues west of Cape Verde (about 46°30' W longitude). On the day the treaty was signed, June 7, 1494, Columbus was sailing along the southern coast of Cuba. He was exploring that long coast without much success. On June 12, Columbus gathered his crew on Evangelista island (now Isla de la Juventud). He made them all swear an oath, in front of a notary, that Cuba was not an island but indeed the mainland of Asia. They swore that China could be reached by land from there.

Different Versions of the Letter

There are two known versions of the Spanish letter to Santangel. There are at least six versions of the Latin letter to Gabriel Sanchez published in the first year (1493). Plus, there's an Italian verse version by Giuliano Dati, which had five editions. Besides the Italian verse, the first translation into another language was German in 1497. In total, seventeen versions of the letter were published between 1493 and 1497. A handwritten copy of the letter to the Catholic monarchs, found in 1985, was not printed until recently.

Spanish Letter to Luis de Santangel

This letter was written and printed in Spanish. It is usually thought to be from the copy Columbus sent to Luis de Santángel, the Escribano de Racion of the Crown of Aragon. However, no recipient is named in the letter itself; it's just addressed to "Señor."

- 1. Barcelona edition: This version has no title, is in folio size, and is undated with no printer named. Because of some spellings influenced by Catalan, it was believed to be printed in Barcelona. It's thought to have been printed in late March or early April 1493. Only one copy of this edition has ever been found. It was discovered in 1889 and is now at the New York Public Library.

- 2. Ambrosian edition: This version is in quarto size, with no date, printer name, or location. It was found in 1856 at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan.

These editions were not mentioned by any writers before the 1800s, and no other copies have been found. This suggests they were very small printings. It's possible that the publication of Columbus's letter was stopped in Spain by royal order.

Latin Letter to Gabriel Sanchez

The first printed version of the Latin translation of Columbus's letter was likely printed in Rome by Stephen Plannck around May 1493. Most other early Latin versions are reprints of that one. The title is De Insulis Indiae supra Gangem nuper inventis ("Of the islands of India beyond the Ganges, recently discovered"). It includes a beginning note saying it was sent by Christopher Columbus to "Raphael Sanxis" (later versions corrected this to "Gabriel Sanchez"), the treasurer of the Crown of Aragon. Its opening greeting praises Ferdinand II of Aragon. It also says the translator was the notary "Aliander de Cosco" (later corrected to "Leander de Cosco"), who finished translating it on April 29, 1493.

All the Latin versions leave out the endings found in the Spanish letter to Santangel. They don't include the sign-off about being written on the ship in the Canaries. They also omit the update about the storm and how many days it took to return. Instead, it simply ends with "Lisbon, the day before the Ides of March" (May 14). Columbus's signature is given as "Christoforus Colom Oceanice classis Præfectus" ("Christopher Columbus, Prefect (or Admiral) of the Ocean fleet"). At the end, there is a short poem praising Ferdinand II, written by Leonardus de Corbaria, Bishop of Monte Peloso.

For a long time, historians believed the Latin version was based on the copy of the letter Columbus sent to the Catholic monarchs. They thought Columbus's address to the treasurer Gabriel Sanchez was just a polite formality. According to this idea, Columbus's original letter was read in Spanish to the monarchs in Barcelona. Then Ferdinand II (or his treasurer Gabriel Sanchez) ordered the notary Leander de Cosco to translate it into Latin. The translation was finished by April 29, 1493. The handwritten copy was then taken or received by the Neapolitan church leader Leonardus de Corbaria, Bishop of Monte Peloso. He took it to Rome and arranged for it to be printed there by Stephanus Plannck around May 1493. The Roman version was then carried into Central Europe and reprinted in Basel (twice, 1493 and 1494), Paris (three times in 1493), and Antwerp (once, 1493). A corrected Roman version was printed by two different publishers in late 1493.

- 3. First Roman edition: Undated and unnamed, but likely printed by Stephanus Plannck in Rome around May 1493. It was plain text and looked like it was printed quickly.

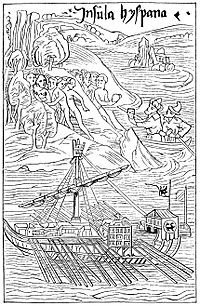

- 4. First Basel edition: This is the only early edition missing "Indie supra Gangem" in the title. It seems to be a reprint of the first Roman edition. It's the first edition with pictures, including eight woodcuts.

- 5. First Paris edition: Directly from the first Roman edition. Printed in Paris.

- 6. Second Paris edition: Likely by Guyot Marchant of Paris, a direct reprint of the first Paris edition.

- 7. Third Paris edition: A reprint of the previous Paris edition, with the printer's mark identifying Guyot Marchant.

- 8. Antwerp edition: By Thierry Martins in Antwerp, 1493, directly from the first Roman edition.

- 9. Second Roman edition: Undated and unnamed, likely by Stephen Plannck in Rome. This is a corrected version, probably released in late 1493.

- 10. Third Roman edition: By the Roman printer Franck Silber. This is the first edition to be clearly dated and have the printer's name. It's also a corrected version.

- 11. Second Basel edition: Dated and named, printed by Johann Bergmann in Basel, April 21, 1494. This is a reprint of the first Basel edition and was published as an extra part of a play.

Italian Verse and German Translations

The Latin letter to Gabriel Sanchez was translated into Italian poetry by Giuliano Dati, a popular poet. This was done at the request of Giovanni Filippo dal Legname, who was secretary to Ferdinand II. The first edition of the Italian verse version was published in June 1493. It quickly went through four more editions, suggesting it was probably the most popular form of Columbus's letter, at least among the Italian public. A translation of the Latin letter into German prose was done in 1497.

- 12. First Italian verse edition: By Giuliano Dati, published by Eucharius Silber in Rome, dated June 15, 1493.

- 13. Second Italian verse edition: A revised translation by Giuliano Dati, printed in Florence by Laurentius de Morganius and Johann Petri, dated October 26, 1493.

- 14. Third Italian verse edition: A reprint of Dati's verse edition.

- 15. Fourth Italian verse edition: A reprint of Dati's verse, by Morganius and Petri in Florence, dated October 26, 1495.

- 16. Fifth Italian verse edition: A reprint of Dati's verse, undated and unnamed (after 1495).

- 17. German translation: Translated into German in Strassburg, printed by Bartholomeus Kistler, dated September 30, 1497.

Letter to the Catholic Monarchs (Libro Copiador)

This handwritten letter was unknown until it was found in 1985. It was part of a collection called the Libro Copiador. This book contained handwritten copies of nine letters Columbus wrote to the Catholic Monarchs, dated from March 4, 1493, to October 15, 1495. Seven of these nine letters had never been known before. Its discovery was announced in 1985. The Spanish government bought it in 1987, and it's now kept at the General Archive of the Indies in Seville.

Even though experts have generally accepted the Libro Copiador as likely real, it's still being carefully studied. The first letter in the copybook claims to be a copy of the original letter Christopher Columbus sent to the Catholic Monarchs from Lisbon, announcing his discovery. If it's real, it came before the Barcelona edition and all other known versions of the letter. It has big differences from both the Spanish letter to Santangel and the Latin letter to Sanchez. It includes more details about what the native people reported, including island names not mentioned before (like "Cuba," "Jamaica," "Boriquen," and "Caribo"). It also has a strange idea about using money from the Indies to start a crusade to conquer Jerusalem. It leaves out some of the economic details found in the printed versions. If it's real, this letter helps solve the "Sanchez problem." It confirms that the Latin letter to Gabriel Sanchez is not a translation of the letter Columbus sent to the Monarchs. It strongly suggests that the Sanchez letter is just a Latin translation of the letter Columbus sent to Luis de Santangel.

Thefts, Forgeries, and Returns

Many copies of the letter were made through forgery from stolen copies from various libraries, including the Vatican Library. These fake copies were then sold to collectors and other libraries, who were tricked. The Vatican's stolen copy was returned in January 2020. These forgeries and thefts have been the subject of intense international investigations and forensic reports. Other suspected thefts, forgeries, and sales are still being looked into.

Online Resources

- The Spanish letter of Columbus to Luis de Sant' Angel, Escribano de Racion of the Kingdom of Aragon, dated February 15, 1493, 1893 edition, London: Quaritch.: fascimile and transcription of the Barcelona edition of 1493, with English translation by M.P. Kerney. For an html version of the same letter, see transcription, with English translation at King's College London. (accessed February 12, 2012).

- Lettera in lingua spagnuola diretta da Cristoforo Colombo a Luis de Santangel (15 febbrajo 14 marzo 1493), riproddotta a fascimili, Gerolamo d'Adda, editor, 1866, Milan: Laengner, contains a fascimile of the Ambrosian edition of the Spanish letter to Santangel. Lettere autografe di Cristoforo Colombo nuovamente stampate. G.Daelli, editor, 1863 (with foreword by Cesare Correnti), Milan: Daelli, contains the first transcription (in Spanish) and an Italian translation of the Ambrosian edition.

- Historia de los Reyes Católicos D. Fernando y Da Isabel: crónica inédita del siglo XV, 1856 ed., Granada: Zamora, written at the end of the 15th century by Andrés Bernáldez contains what seems like a paraphrasing of Columbus's letter to Santangel, Vol. 1, Ch. CXVIII, (pp. 269–77).

- "Carta del Almirante Cristobal Colon, escrita al Escribano de Racion de los Señores Reyes Catolicos", in Colección de los viages y descubrimientos que hicieron por mar los españoles desde fines del siglo XV, Martín Fernández de Navarrete, 1825, vol. 1, Madrid: pp. 167–75, is the first known modern publication of the Spanish letter to Santangel. Navarrete's transcription is based on a copy (now lost) originally copied by Tomas Gonzalez from an unknown edition (also lost) at the royal archives of Simancas in 1818.

- Primera Epístola del Almirante Don Cristóbal Colón dando cuenta de su gran descubrimiento á D. Gabriel Sánchez, tesorero de Aragón, edited by "Genaro H. de Volafan" (pseudonym of Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagen), 1858, Valencia: Garin. Contains the only transcription of a Spanish manuscript of the letter found by Varnhagen at the Colegio Mayor de Cuencas (manuscript since lost). It is accompanied bilingually by the transcription of the Latin from the third Roman (Silber) edition of 1493.

- The Latin letter of Columbus: printed in 1493 and announcing the discovery of America, Bernard Quaritch, editor, 1893, London: contains fascimile of the second Roman edition (Plannck) of 1493; no transcription nor English translation provided.

- "A Letter addressed to the noble Lord Raphael Sanchez, &tc.", in R.H. Major, editor, 1848, Select Letters of Christopher Columbus, with other original documents relating to his four voyages to the New World. London: Hakluyt, (pp. 1–17) contains bilingually a Latin transcription and English translation of the third Roman (Silber) edition.

- "La Lettera dellisole che ha trovato nuovamente il Re Dispagna", Italian verse translation by Giuliano Dati, from Florence edition (October 1493), transcribed (without translation) in R.H. Major (1848: pp. lxxiii–xc).

- "The Columbus Letter: Concerning the Islands Recently Discovered in the Indian Sea", at the University of Southern Maine: fascimile, Latin transcription and English translation, of the 1494 second Basel edition, with introduction and comments by Matthew H. Edney (1996, rev.2009), at the Osher Map Library, Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine (accessed February 12, 2012).

- "Carta a los Reyes de 4 Marzo 1493", Spanish transcription and English translation, of the manuscript letter to the Catholic Monarchs, from the Libro Copiador, reproduced in Margarita Zamora (1993) Reading Columbus, Berkeley: University of California press. (online at UC Pres E-Books collection, accessed February 12, 2012).

See also

In Spanish: Cartas que anunciaron el descubrimiento de las Indias para niños

In Spanish: Cartas que anunciaron el descubrimiento de las Indias para niños

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |