English people facts for kids

English people are people who were born in England, which is a country in the United Kingdom. Most English people speak the English language. Over many years, lots of English people have moved to other countries, like the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.

England is one of the nations on the island of Great Britain. English people share this island with Scottish people and the Welsh. The English people are descended from many different groups who came to England from all over Europe.

Contents

Who are the English People?

Early History

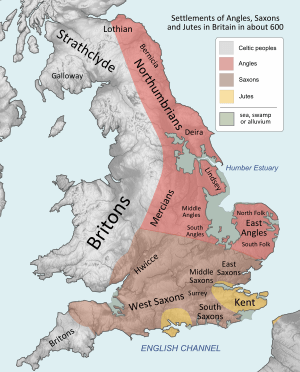

The first people to be called 'English' were the Anglo-Saxons. These were groups of Germanic tribes. They started moving to eastern and southern Great Britain in the 5th century AD. This happened after the Romans left Britain. The Anglo-Saxons gave their name to England. Engla land means "Land of the Angles." They also gave their name to the English language.

When the Anglo-Saxons arrived, the land was already home to people called the 'Romano-British'. These were the descendants of the native people who spoke Brythonic languages. They had lived in Britain under Roman rule for centuries. The Roman Empire had people from many different places. So, a few other groups might have been in England before the Anglo-Saxons. For example, there is proof that some North Africans were in a Roman army camp.

How the Anglo-Saxons arrived and how they got along with the Romano-British is still debated. For a long time, people thought that many Anglo-Saxon tribes invaded. They believed these tribes mostly pushed out the native British people. This idea was supported by old writings from the time. However, new studies, including genetic research, suggest that many British people stayed. They were likely ruled by the new Germanic leaders. Some even married into these new families.

In 2016, scientists studied ancient DNA from burials. They found proof that Anglo-Saxons and native people married each other early on. They also estimated that about 25–40% of modern English people's genes come from these early 'Anglo-Saxon' groups.

Vikings and the Danelaw

Around 800 AD, Danish Vikings started attacking the coasts of the British Isles. After these attacks, many Danish settlers came to England. At first, Vikings were seen as very different from the English. This difference was made official when Alfred the Great signed a treaty. This Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum divided England. The Danes ruled northern and eastern England, an area called the Danelaw.

However, Alfred's successors later won battles against the Danes. They brought much of the Danelaw into the new kingdom of England. Danish invasions continued into the 11th century. During this time, there were both English and Danish kings. For example, Æthelred II was English, but Cnut was Danish.

Over time, the Danes in England began to be seen as 'English'. They had a big impact on the English language. Many English words, like anger, ball, egg, knife, and they, come from Old Norse, the Viking language. Also, place names ending in -thwaite and -by are from Scandinavia.

England Becomes One Country

The English people were not united under one government until the 10th century. Before that, England was made up of many small kingdoms. These slowly joined together into seven powerful states, known as the Heptarchy. The strongest of these were Mercia and Wessex. The English nation state began to form when the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms united. They came together to fight against the Danish Viking invasions. After 959, England remained a united country.

The nation of England was officially formed in 937. This happened when Æthelstan of Wessex won the Battle of Brunanburh. Wessex grew from a small kingdom in the southwest. It became the founder of the Kingdom of the English. It brought together all the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and the Danelaw.

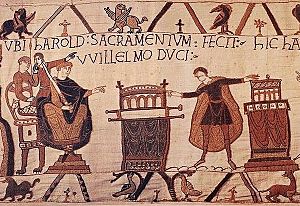

Norman and Angevin Rule

The Norman conquest of England happened in 1066. This ended Anglo-Saxon and Danish rule in England. A new French-speaking Norman ruling class took over. They replaced almost all the Anglo-Saxon nobles and church leaders. After the conquest, "English" usually meant all people born in England. This included those of Anglo-Saxon, Scandinavian, or Celtic background. This was to tell them apart from the Norman invaders. The Normans were still called "Norman" even if they were born in England, for a generation or two. The Norman family ruled England for 87 years. Then, in 1154, Henry II from the House of Plantagenet (based in France) became king. England then became part of the Angevin Empire until 1399.

Many sources from that time suggest that within 50 years, most Normans outside the royal court started speaking English. The Anglo-Norman language remained important for government and law. Over time, the English language became more important even in the royal court. The Normans slowly became part of English society. By the 14th century, both rulers and common people saw themselves as English and spoke English.

There was a legal rule called Presentment of Englishry. This rule meant that if an unknown murdered body was found, the local area had to prove it was an Englishman, not a Norman. If they couldn't, they paid a fine. This law was removed in 1340.

In the United Kingdom

(Ireland)

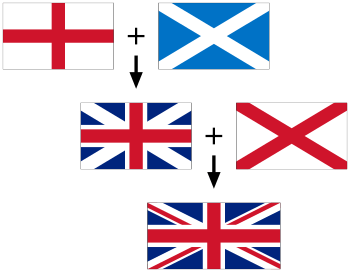

Since the 18th century, England has been part of a larger country called the United Kingdom. Wales became part of England through laws passed between 1535 and 1542. Later, in 1707, England and Scotland joined together. This created the Kingdom of Great Britain. In 1801, Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland also joined. This formed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. In 1922, most of Ireland left the UK to form the Irish Free State. The rest became the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Throughout the UK's history, the English have been the largest group. They have also had a lot of political power. Because of this, being 'English' and being 'British' often feel very similar. After 1707, people in the British Isles were encouraged to think of themselves as British.

New People Arrive and Settle In

England has welcomed many different groups of people over the centuries. Some of these groups try to keep their own separate identity. Others have blended in and married with English people. For example, after 1656, many Jewish people came to England. They came from places like Russia and Germany.

In 1685, the French king made Protestantism illegal. About 50,000 Protestant Huguenots then fled to England. Also, many Irish people have moved to England over time. Today, about 6 million people in the UK have at least one grandparent born in the Republic of Ireland.

There have been black people in England since the 16th century because of the slave trade. Indian people have been present since at least the 17th century. This was due to the East India Company and the British Raj. Black and Asian populations have grown in the UK. This happened because immigration from the British Empire and the Commonwealth of Nations was encouraged. This helped with worker shortages after World War II. However, these groups are often still seen as minorities. Research shows that black and Asian people in the UK often identify as British. They are less likely to identify with one of the UK's four nations, like England.

English People in Other Countries

| Number of English people living abroad | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | % of the local population | |||

| 2011 Australia Census | 7,238,533 | 36.1 |

|

||

| 2011 Scotland Census | 459,486 | 8.68 |

|

||

| 2013 United States ACS | 27,657,961 | 7.7 |

|

||

| 2011 Canada Census | 6,509,500 | 19.81 |

|

||

English people have always moved from England to other parts of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. However, it's hard to know exactly how many. This is because British censuses haven't usually asked people to say if they are English. But the census does record where people were born. It shows that 8.08% of Scotland's population, 3.66% of Northern Ireland's, and 20% of Wales's population were born in England.

Large groups of people descended from English colonists and immigrants live in the United States, Canada, Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand.

United States

In 2013, English Americans made up about 7.7% of the total United States population. This was behind German Americans (14.6%) and Irish Americans (10.5%). However, experts believe this number is too low. Many people of English background might just say they are "American". Or, if they have mixed European roots, they might identify with a more recent group.

In the 2000 United States Census, over 24.5 million Americans said their ancestry was fully or partly English. Another 1 million said they had British ancestry.

In the 1980 Census, over 49 million Americans claimed English ancestry. At that time, this was about 26.34% of the total population. This would make them the largest ethnic group in the United States even today. Six out of the ten most common surnames in the United States are of English origin.

Americans with English heritage are often seen, and see themselves, as simply "American." This is because of the many historical and cultural links between England and the U.S.

Canada

In the 2006 Canadian Census, 'English' was the most common ethnic origin. This means 6,570,015 people said they were fully or partly English. This was 16% of the population. However, some people who now say they are Canadian might have identified as English before.

Australia

From the start of the colonial era until the mid-20th century, most settlers in Australia came from the British Isles. The English were the largest group, followed by the Irish and Scottish.

In the 2011 census, 7.2 million people, or 36.1% of those who answered, identified as "English" or a mix including English. The census also showed that 910,000 people living in Australia were born in England.

Other Communities Around the World

Since the 1980s, many English people have moved to Spain and France. It's estimated that over 3 million English people live there permanently or part-time. They are drawn by the warmer weather and cheaper houses.

Many people with some English ancestry also live in New Zealand, South Africa, and South America.

Images for kids

-

A page from the Book of Lindisfarne, a famous old book.

-

A copy of the Sutton Hoo helmet, found in an Anglo-Saxon burial.

-

A scene from the Bayeux Tapestry showing the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

-

William Henry Hudson was an author and naturalist from Argentina, but he had English roots.

-

Wells Cathedral in Somerset, a beautiful old church.

-

People celebrating Saint George's Day in Trafalgar Square in 2010.

-

Geoffrey Chaucer was a famous English poet. He is best known for The Canterbury Tales.

See also

In Spanish: Ingleses para niños

In Spanish: Ingleses para niños