Golding Bird facts for kids

Golding Bird (born December 9, 1814 – died October 27, 1854) was an important British doctor and scientist. He was a member of the Royal College of Physicians, a group of highly respected doctors. Bird became an expert on kidney diseases and wrote a detailed paper about problems with urine in 1844.

He was also known for his work in other sciences, especially how electricity could be used in medicine and in electrochemistry (the study of how electricity and chemical reactions are linked). From 1836, he taught at Guy's Hospital in London, a famous teaching hospital. He also wrote a popular science textbook for medical students called Elements of Natural Philosophy.

Golding Bird became interested in chemistry when he was a child, mostly by teaching himself. He was so good that he even gave lectures to his school friends! Later, he used his chemistry knowledge in medicine, doing a lot of research on the chemistry of urine and kidney stones. In 1842, he was the first to describe a condition called oxaluria, which causes a specific type of kidney stone to form.

Bird was a member of the London Electrical Society. He was very creative in using electricity for medical treatments and even designed much of his own equipment. At that time, many fake doctors used electricity, which gave it a bad name. Bird worked hard to stop these "quacks" and helped make medical electrotherapy a respected treatment. He was quick to use new tools. For example, he invented a new type of Daniell cell (a kind of battery) in 1837 and made important discoveries in electrometallurgy (using electricity to work with metals) with it. He also designed a flexible stethoscope and wrote the first description of such a tool in 1840.

Bird had poor health throughout his life and sadly died at the age of 39.

Contents

Life and Early Career

Golding Bird was born in Downham, Norfolk, England, on December 9, 1814. His father, also named Golding Bird, worked for the government in Ireland. His mother, Marrianne, was Irish. Golding was very smart and ambitious from a young age. However, he had rheumatic fever as a child, which affected his posture and left him with weak health for his whole life.

He went to school in Wallingford, Berkshire, where he learned classical subjects and developed a habit of studying on his own. From age 12, he went to a private school in London that didn't teach much science. But Bird was so far ahead of his teachers in science that he gave chemistry and botany lectures to his classmates! He had four younger brothers and sisters. One of his brothers, Frederic, also became a doctor and wrote about plants.

Becoming a Doctor

In 1829, when he was 14, Bird left school to train with an apothecary (a type of pharmacist and doctor) named William Pretty in London. He finished his training in 1833. In 1836, he received his license to practice medicine from the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries. He got this license without taking an exam because he was already well-known as a talented student at Guy's Hospital. He had started studying medicine there in 1832 while still doing his apprenticeship.

At Guy's, he was greatly influenced by Thomas Addison, a doctor who quickly saw Bird's talents. Bird was a very ambitious and skilled student. Early in his career, he became a Fellow of the Senior Physical Society, which required him to write a special paper. He won prizes for medicine, obstetrics (childbirth care), and ophthalmic surgery (eye surgery) at Guy's. He also won a silver medal for botany. Around 1839–1840, he worked on breast diseases at Guy's, helping Sir Astley Cooper, a famous surgeon.

Bird earned his medical degree (MD) from the University of St Andrews in 1838 and a Master of Arts (MA) in 1840. He got these degrees while still working in London. At that time, St Andrews didn't require students to live there or take exams for an MD. Bird got his degree by submitting letters from other qualified doctors, which was a common practice.

In 1838, at age 23, he started his own general practice in London. At first, he wasn't very successful because he was so young. However, in the same year, he became a doctor at the Finsbury Dispensary, a clinic for the poor, and stayed there for five years. By 1842, his private practice was earning him a good income. He became a member of the Royal College of Physicians in 1840 and a full fellow in 1845.

Teaching and Research

Bird taught about natural philosophy (which included physics), medical botany (the study of plants for medicine), and urinary pathology (diseases of the urinary system) at Guy's Hospital from 1836 to 1853. He also taught about materia medica (the study of medicines) at Guy's and at the Royal College of Physicians. He published many articles and books throughout his career, not just on medical topics, but also on electricity and chemistry.

In 1836, Bird became the first head of the electricity and galvanism (a type of electricity) department at Guy's. This was before he even graduated as a doctor! In 1843, he became an assistant physician at Guy's and was put in charge of the children's outpatient ward. Like his electrotherapy patients, these children were often from poor families and couldn't afford medical care. They were often used for training medical students. At that time, it was common to use poor patients for experimental treatments without their permission. Bird wrote reports on childhood diseases based on his work with these children.

Family Life and Later Years

In 1842, Golding Bird married Mary Ann Brett. They moved from his family home to a new house. They had two daughters and three sons. One of their sons, Cuthbert Hilton Golding-Bird, became a famous surgeon. Another son, Percival, became a priest.

Bird was a member of several important scientific groups, including the Linnean Society of London (for natural history), the Geological Society of London, and the Royal Society (a very old and respected scientific group). He also joined the Pathological Society of London when it started in 1846. He was part of the London Electrical Society, which was known for its exciting demonstrations of new electrical machines. Bird was also a Freemason from 1841 to 1853.

Bird was ambitious and sometimes got into arguments with others, especially in medical journals. However, he was known for giving his patients his full attention and care. He was also a great speaker and debater.

Around 1848 or 1849, Bird was diagnosed with heart disease by his brother. He had to stop working for a while. But by 1850, he was working harder than ever and had so many patients that he moved to a bigger house. In 1851, severe rheumatism (a painful joint condition) forced him to take a long holiday with his wife in Tenby. Even on holiday, his fame meant he received many requests for medical advice. He bought a retirement estate in Royal Tunbridge Wells in 1853, but he couldn't leave London until June 1854. He continued to see patients at his home, even though his health was getting much worse.

Golding Bird died on October 27, 1854, at his new home. He was suffering from a urinary tract infection and kidney stones. His early death at 39 was likely due to his lifelong poor health and working too hard. He is buried in Woodbury Park Cemetery in Tunbridge Wells.

After his death, his wife Mary created the Golding Bird Gold Medal and Scholarship for sanitary science (later for bacteriology). This award was given every year at Guy's Hospital and continued for many years.

Science and Medicine

Golding Bird was very interested in "collateral sciences." These are sciences like physics, chemistry, and botany that are important for medicine but aren't medicine themselves. For a long time, doctors didn't use much chemical analysis to diagnose illnesses. But Bird and others at Guy's Hospital changed that.

Bird was especially influenced by William Prout, an expert in chemical physiology (the study of how chemicals work in the body). Bird became famous for his chemistry knowledge. For example, in 1832, he criticized a test for arsenic poisoning. He said the test wasn't reliable because other things could give the same false positive result.

Bird also disagreed with Prout's ideas about urine. In 1834, Bird and his future brother-in-law, R. H. Brett, published a paper arguing against Prout's claim about a pink sediment in urine. Even though Bird was still a student, Prout felt he had to respond! In 1843, Bird tried to identify this pink compound, calling it purpurine. Today, we know it as uroerythrin.

Around 1839, a famous surgeon, Astley Cooper, asked Bird to write about the chemistry of milk for his book on breast disease. Bird also published his own textbook, Elements of Natural Philosophy, for medical students. He thought other physics books were too mathematical, so he wrote his with clear explanations. It was very popular and stayed in print for 30 years.

Electricity in Medicine

In 1836, Bird was put in charge of the new electricity and galvanism department at Guy's Hospital. Using electricity for treatment was still very new and experimental. Bird used different types of electrical machines to treat many conditions, like some forms of chorea (a movement disorder). Treatments included stimulating nerves and muscles, and even electric shock therapy. Bird also invented the electric moxa to help heal skin ulcers.

Electrical Equipment

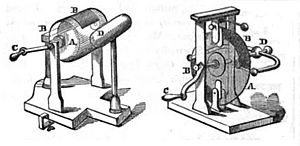

Scientists like Michael Faraday had shown that electricity and galvanism were the same. But Bird still separated his machines into "electrical machines" (high voltage, low current) and "galvanic apparatus" (high current, low voltage). His galvanic equipment included electrochemical cells like the voltaic pile and the Daniell cell (a type of battery). Bird even made his own version of the Daniell cell. He also used induction coils with batteries to deliver electric shocks.

The "electrical machines" were electrostatic generators that used friction. They had a spinning glass disc or cylinder with silk flaps that rubbed against them. These machines had to be turned by hand during treatment. Small amounts of static electricity could be stored in Leyden jars for later use.

By 1849, newer generators based on Faraday's discoveries were available. Bird started recommending them in his lectures. Old galvanic cells were messy because of the acids, and electrostatic generators needed a lot of skill to use. The new electromagnetic machines were much easier. Bird's only complaint was that cheaper ones produced alternating current, but for medical uses, especially for nerves, a steady, one-way current was often needed.

Bird showed how important the direction of current was. For example, he experimented with a living frog's leg. He showed that stimulating the sciatic nerve in one direction caused muscle movement, but reversing the current did not. He also described experiments on human senses, like one where electricity passed through a person's head caused them to hear sounds.

Bird designed his own automatic interrupter circuit for giving shocks. Older ones needed someone to turn a wheel, but Bird wanted his hands free to treat the patient more precisely. His device switched the current on and off quickly using magnets. He also made a special "unidirectional interrupter" to ensure the current flowed in only one direction, which was important for some treatments.

Electrical Treatments

Doctors used three main types of electrotherapy. One was the electric bath. The patient sat on an insulated stool and was connected to an electrical machine, becoming "charged" with electricity. The second treatment involved bringing a negative electrode close to the patient, often near the spine, to create sparks. Different shaped electrodes were used for different body parts. These treatments often caused the skin to blister. The third type was electric shock therapy, which delivered a stronger shock from a battery or generator through an induction coil.

Electric stimulation was used for nerve problems where the body couldn't properly stimulate glands or muscles. Bird used his equipment to treat Sydenham's chorea (a movement disorder), other forms of spasm, some types of paralysis, and to help bring on menstruation (periods) if they had stopped.

Electric shock treatment was popular with the public, but many doctors were wary because of fake practitioners who claimed it could cure anything. Bird, however, believed in the treatment when used correctly. He convinced his boss, Addison, of its value. Addison even wrote the first paper about their work, which helped make the treatment more accepted by other doctors. Bird also spoke out against the many fake medical electricians, helping to make electrical treatment respected again in the medical field.

Electric Moxa

Bird invented the electric moxa in 1843. The name comes from an old Chinese healing method called moxibustion. Bird's electric moxa was used to create a small, healing sore on the skin. This was done to treat inflammation or congestion by drawing out bad humors, a technique called counter-irritation. Before Bird's invention, these sores were made using much more painful methods, like burning charcoal.

Bird's device used a silver electrode and a zinc electrode connected by copper wire. Two small blisters were made on the skin, and the electrodes were attached for a few days. The body's own fluids created electricity between the metals. The blister under the silver electrode healed, but the one under the zinc electrode produced the desired healing sore.

Bird realized that the electric moxa could also be used to heal stubborn leg ulcers, which were common among working-class people. Hospitals couldn't admit everyone with ulcers, so the moxa allowed them to be treated as outpatients. The silver electrode was placed on the ulcer, and the zinc electrode was placed a few inches away on a small cut in the skin. The whole thing was then bandaged. Later, another doctor found that cutting the skin under the zinc plate wasn't even necessary; just moistening it with vinegar worked.

Electrochemistry Discoveries

Bird used his position at Guy's to do more research and teach his students. He was very interested in electrolysis (using electricity to cause chemical changes). He repeated experiments to extract metals using electricity and wanted to see if this method could find tiny amounts of heavy metal poisons.

In 1837, Bird began studying how copper plates formed in the Daniell cell (a type of battery). He succeeded in coating a mercury surface with sodium, potassium, and ammonium using solutions of their salts. He even got beryllium, aluminum, and silicon from their salts and oxides.

In the same year, Bird built his own version of the Daniell cell. His new idea was to put the two solutions (copper sulphate and zinc sulphate) in the same container, but separated by a barrier of Plaster of Paris. Plaster of Paris is porous, meaning it has tiny holes, so it allowed ions (charged particles) to cross but kept the solutions from mixing. This was the first "single-cell" Daniell cell, and it led to the later invention of the porous pot cell.

Bird's experiments with his cell were important for the new field of electrometallurgy. He made a surprising discovery: copper would deposit on and inside the plaster barrier itself, even without touching the metal electrodes! When he broke the plaster, he found veins of copper running through it. This was so unexpected that some scientists, including Faraday, didn't believe it at first. Before this, metal deposition had only been seen on metal electrodes. Bird's discovery is the principle behind electrotyping (making copies of objects using electricity). However, Bird himself didn't use this discovery for practical purposes or work in metallurgy.

Bird believed there was a connection between how the nervous system works and the processes he saw in electrolysis with very small, steady currents. He knew the currents were similar in strength. To Bird, if this connection existed, it made electrochemistry very important for understanding biology.

Chemistry Research

Arsenic Poisoning

In 1837, Bird helped investigate the dangers of cheap candles that contained arsenic. These candles burned brighter because of the arsenic, making them popular. Bird analyzed the candles and found that manufacturers had recently increased the amount of arsenic in them. He also confirmed that arsenic became airborne when the candles burned.

The researchers exposed animals and birds to the candles. The animals survived, but the birds died. Bird examined the birds and found small amounts of arsenic in their bodies. However, he found large amounts of arsenic in their drinking water, suggesting that was how they were poisoned, not by breathing the air.

Carbon Monoxide Poisoning

For a long time, people didn't realize that carbon monoxide poisoning was the cause of death from stoves burning fuels like charcoal. In 1838, a night watchman died after spending the night by a new charcoal stove. The investigation concluded he died from carbonic acid (which is carbon dioxide), not carbon monoxide. Both Bird and John Snow (who later became famous for his public health work) supported this idea at first. Bird himself felt sick while collecting air samples near the stove.

However, the stove makers argued that the death was caused by something else. Bird later clarified that any stove burning fuel without a chimney or good ventilation was dangerous. In 1839, Bird presented a paper about his tests on sparrows poisoned by carbon fumes. This paper was important and led to him sharing his views with the British Association. Bird also published a detailed paper in Guy's Hospital Reports with many case studies. He realized that some poisonings from stoves were due to something other than carbonic acid, though he still hadn't identified it as carbon monoxide.

Urology and Kidney Stones

Bird did a lot of research in urology (the study of the urinary system), including the chemistry of urine and kidney stones. He quickly became a recognized expert. His writings on urinary sediments and kidney stones were the most advanced of his time. He was influenced by the work of Alexander Marcet and William Prout.

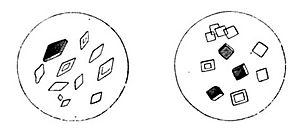

Bird studied and categorized the collection of kidney stones at Guy's Hospital. He focused on the crystal structures of the "nuclei" (the tiny starting points) of the stones, believing their chemistry was key to stone formation. He identified many types of stones, classifying them by the chemistry of their nuclei. He divided them into two main groups: organic stones (caused by a body process gone wrong) and stones from too many inorganic salts that formed sediment.

In 1842, Bird was the first to describe oxaluria, sometimes called Bird's disease. This condition is sometimes caused by too much oxalate of lime in the urine. This is the most common type of kidney stone. Today, we know that the most common cause of kidney stones is too much calcium in the urine, not oxalate itself, though calcium oxalate stones are the most common type. Some people do have too much oxalate in their urine, which can be linked to diet, genetics, or gut problems.

In his major work, Urinary Deposits, Bird spent a lot of time explaining how to identify chemicals in urine by looking at crystals under a microscope. He showed how the same chemical's crystals could look very different depending on conditions, especially with disease. Urinary Deposits became a standard textbook and was reprinted five times.

Bird was also the first to realize that certain forms of urinary casts (tiny cylinders found in urine) could indicate Bright's disease (a kidney disease). Casts are microscopic tubes of protein that form in the kidneys and are released into the urine. Today, we know that these casts are normal unless they contain cells, which then point to a kidney problem.

Vitalism and Chemistry

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, many people believed that illness was due to the condition of the whole body. They thought a "vital force" controlled chemical processes in living things. This theory said that organic compounds (chemicals from living things) could only be made inside living organisms. But this idea was proven wrong in 1828 when Friedrich Wöhler made urea (an organic compound) from non-living chemicals. Still, the "vital force" was often used to explain organic chemistry in Bird's time.

Around the mid-1800s, a new way of thinking began, especially among younger doctors like Bird and Snow. They were excited by new discoveries in chemistry. For the first time, doctors could link specific chemical reactions to specific organs in the body.

Bird helped to change the old way of thinking by showing that specific chemical processes happen in specific organs, not just in the whole animal. He challenged some ideas from the famous chemist Justus von Liebig. For example, Liebig thought the ratio of uric acid to urea would depend on how active a person was, but Bird showed this wasn't true. Bird also felt it wasn't enough to just count atoms, as Liebig did. He believed doctors needed to explain why atoms combined in certain ways, and he tried to use electrical forces, not a "vital force," to explain this.

Flexible Stethoscope

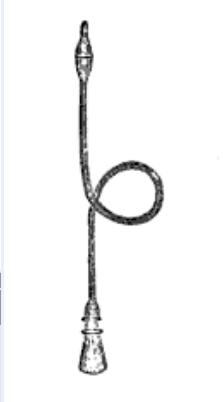

Golding Bird designed and used a flexible tube stethoscope in June 1840. In the same year, he published the first description of such an instrument. In his paper, he mentioned an older "snake ear trumpet" used by other doctors, but he thought it had problems, especially its long length, which made it work poorly. Bird's invention looked similar to a modern stethoscope, but it only had one earpiece.

Bird found the flexible stethoscope very convenient. It meant he didn't have to lean uncomfortably over patients, which was especially helpful for him because of his severe rheumatism. He could even apply the stethoscope while sitting down. It also made it easy to pass the earpiece to other doctors and students so they could listen.

Elements of Natural Philosophy

When Golding Bird started teaching science at Guy's Hospital, he couldn't find a good textbook for his medical students. He needed a book that explained physics and chemistry in detail but wasn't too mathematical for them. Bird reluctantly decided to write such a book himself, based on his lectures from 1837–1838. The result was Elements of Natural Philosophy, first published in 1839.

The book became incredibly popular, even outside of medical schools, and went through six editions. It was still being reprinted more than 30 years later in 1868. After Bird's death, his friend Charles Brooke edited the fourth edition and added some of the mathematical details Bird had left out. Brooke continued to update the book for later editions.

The book was well-received and praised for how clear it was. One reviewer said it taught "the elements of the entire circle of natural philosophy in the clearest and most perspicuous manner." They even recommended it for anyone who wanted to learn about the world around them.

Medical journals were also positive, calling it "a good and concise elementary treatise... presenting in a readable and intelligible form, a great mass of information not to be found in any other single treatise." They noted it was especially good for students who hadn't studied physics before. The sections on magnetism, electricity, and light were particularly recommended.

Later, when the 6th edition came out, reviewers noted that Brooke had updated the book so much that it had become his own. They remembered "the Golding Bird" book fondly from their student days. They approved of the many new descriptions of the latest technology, like new types of dynamos and the spectroscope.

The book covered a wide range of physics topics. The first edition in 1839 included statics (forces at rest), dynamics (forces in motion), gravitation, mechanics, hydrostatics (fluids at rest), pneumatics (gases), hydrodynamics (fluids in motion), acoustics (sound), magnetism, electricity, atmospheric electricity (lightning), electrodynamics (moving electricity), thermoelectricity (heat and electricity), bioelectricity (electricity in living things), light, optics (how light behaves), and polarised light.

In the second edition (1843), Bird added a new chapter on electrolysis, updated the polarized light section, and added two chapters on "thermotics" (which is now called thermodynamics). He also included a chapter on the new technology of photography. Later editions also had a chapter on the electric telegraph. Brooke continued to expand the book, adding new material like the magnetic properties of iron in ships and spectrum analysis.

Works by Golding Bird

- Elements of Natural Philosophy; being an experimental introduction to the study of the physical sciences, London: John Churchill, 1839.

- Lectures on Electricity and Galvanism, in their physiological and therapeutical relations, delivered at the Royal College of Physicians, in March 1847, London: Wilson & Ogilvy, 1847.

- Lectures on the Influence of Researches in Organic Chemistry on Therapeutics, especially in relation to the depuration of the blood, delivered at the Royal College of Physicians, London: Wilson & Ogilvy, 1848.

- Urinary Deposits, their diagnosis, pathology and therapeutical indications, London: John Churchill, 1844.

Images for kids

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |