History of Cameroon facts for kids

Cameroon is a country in West Africa and Central Africa. People have lived there for a very long time, possibly as far back as 130,000 years ago. The oldest signs of humans found so far are from about 30,000 years ago at a place called Shum Laka. The Bamenda highlands in western Cameroon are thought to be where the Bantu peoples came from. Their language and culture later spread across most of central and southern Africa between 1000 BCE and 1000 CE.

European traders first arrived in Cameroon in the 1400s. The name "Cameroon" was given by the Portuguese to the Wouri river. They called it Rio dos Camarões, which means "river of shrimps", because there were many Cameroon ghost shrimp there. Cameroon was also a place where people were taken as slaves during the Transatlantic Slave Trade. In the north, Islamic kingdoms from the Chad basin and the Sahel had a lot of influence. But in the south, many small kings, chieftains, and fons (local rulers) were in charge.

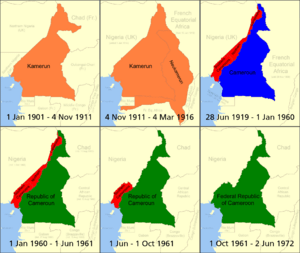

Cameroon became a country as we know it because of European colonization, known as the Scramble for Africa. From 1884, it was a German colony called German Kamerun. Its borders were decided by Germany, Britain, and France. After World War I, the League of Nations mandated France to control most of the land, while the United Kingdom managed a smaller part in the west. After World War II, the United Nations took over, keeping France and Britain in charge of their areas, French Cameroon and British Cameroon.

In 1960, Cameroon became independent. Part of British Cameroons then voted to join the former French Cameroon. Since independence, Cameroon has had only two presidents. Even though other political parties were allowed in 1990, only one party has ever been in power. Cameroon has stayed close friends with France and has mostly sided with Western countries. This has made Cameroon known as one of the most stable countries in its region.

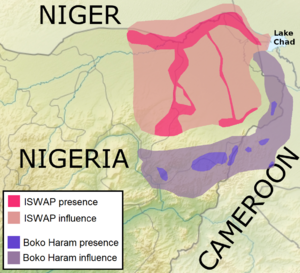

However, things changed in 2017. People in the western part of Cameroon, who speak English (called Anglophone Cameroonians), felt unfairly treated by the government, which mostly speaks French. This led to an ongoing civil war called the Anglophone Crisis. Also, Islamist groups like Boko Haram continue to attack in the north.

In January 2024, Cameroon started the world's first regular program to give out a malaria vaccine. This vaccine, called RTS,S, was approved by the World Health Organization (WHO). It aims to save thousands of African children's lives every year.

Contents

Early History of Cameroon

Ancient Times

Finding old human remains in Cameroon has been difficult because of the warm, wet climate. However, new discoveries and methods are changing this idea. Evidence from Shum Laka in the Northwest Region shows that people lived there 30,000 years ago. In the southern forests, the oldest signs of people are about 7,000 years old. Recent studies suggest that the Iron Age might have begun in southern Cameroon as early as 1000 BCE. It was definitely well-established by 100 BCE.

Scientists who study languages, along with archaeologists and geneticists, believe that the Bantu expansion started in the highlands near the Nigeria-Cameroon border around 1000 BCE. This was a time when Bantu peoples migrated and spread their culture across much of Africa south of the Sahara Desert. Bantu languages spread with these people, along with farming methods and possibly iron tools. They moved first east and then south, creating one of Africa's largest language families. In Cameroon, Bantu people mostly replaced Central African Pygmies like the Baka, who were hunter-gatherers. Today, the Baka live in smaller numbers in the heavily forested southeast. Even though Cameroon was the original home of the Bantu people, the great medieval Bantu-speaking kingdoms grew in other places, like modern-day Kenya, Congo, Angola, and South Africa.

Northern Kingdoms

The earliest known civilization in what is now northern Cameroon is the Sao civilisation. They were known for their amazing terracotta (clay) and bronze artwork. They also built round, walled settlements in the Lake Chad Basin. Not much else is known about them for sure because there are no written records. This culture might have started as early as the fourth century BC. By the end of the first millennium BC, they were definitely living around Lake Chad and near the Chari River. The Sao city-states were strongest between the 9th and 15th centuries AD. The Sao people were either replaced or joined with other groups by the 16th century.

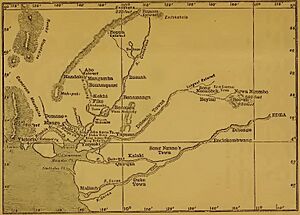

After the Muslim conquest of North Africa in 709, the influence of Islam began to spread south. This happened as trans-Saharan trade grew, reaching into what is now northern Cameroon. The Kanem-Bornu Empire started in what is now Chad and likely fought with the Sao. The Kanem Empire began in Chad in the 8th century. It slowly grew its power north into Libya and south into Nigeria and Cameroon. Slaves taken from raids in the south were their main trade item, along with mined salt. The Empire was Muslim from at least the 11th century. It reached its first peak in the 13th century, controlling most of Chad and smaller parts of nearby countries. After a period of problems, the center of power moved to Bornu. Its capital was at Ngazargamu, in what is now northwestern Nigeria. The Empire slowly got back its land and conquered new areas in modern-day Niger. It started to decline in the 17th century but still controlled much of northern Cameroon.

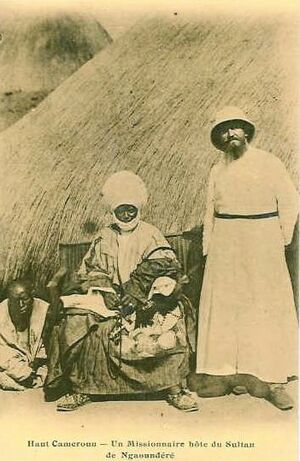

From 1804 to 1808, the Fulani War pushed the Bornu people north out of Cameroon. The Sokoto Caliphate then took control of the region, as well as most of northern Nigeria and large parts of Niger and Mali. This was a feudal empire, meaning local rulers promised loyalty and paid taxes to the Caliph (the main ruler). Northern Cameroon was probably part of the Adamawa Emirate within this Caliphate. This system made it easy for colonial powers to take advantage of the region starting in the 1870s. They tried to weaken the local rulers' ties to the Caliphate.

Southern Regions

The Muslim empires of the Sahara and Sahel never reached further south than the highlands of the Cameroon Line. In the south, there is little archaeological evidence of large empires or kingdoms. There are also no historical records because writing was not used in the region. When the Portuguese arrived in the 16th century, many kings, chiefs, and fons ruled small areas. Many ethnic groups, especially those who speak Grassfields languages in the west, have oral stories about moving south to escape Muslim invaders. This likely refers to the Fulani War and later conflicts in Nigeria and northern Cameroon.

Malaria prevented many Europeans from settling or exploring until the late 1870s. This was when large amounts of quinine, a medicine for malaria, became available. Early Europeans in Cameroon mostly focused on coastal trade and buying slaves. The Cameroon coast was a major place for buying slaves who were taken across the Atlantic Ocean to Brazil, the United States, and the Caribbean. In 1807, the British abolished slavery in their Empire. They began military efforts to stop the slave trade, especially in West Africa. Along with the end of legal slave imports in the United States the same year, the international slave trade in Cameroon dropped sharply. Christian missionaries started to arrive in the late 1800s. Around this time, the Aro Confederacy was growing its economic and political power from southeastern Nigeria into western Cameroon. However, the arrival of British and German colonizers stopped its growth.

Colonial Period

German Kamerun (1884-1918)

The Scramble for Africa began in the late 1870s. European powers wanted to take formal control of parts of Africa that were not yet colonized. The Cameroon coast was interesting to both the British and the Germans. The British were already in what is now Nigeria and had missionary outposts. The Germans had many trading relationships and farms in the Douala region. On July 5, 1884, German explorer Gustav Nachtigal signed agreements with Duala leaders. These agreements made the region a German protectorate (a territory protected and controlled by Germany). A short conflict followed with rival Duala chiefs, which Germany and its allies won. This left the British with no choice but to accept Germany's claim. The borders of modern Cameroon were set through talks with the British and French.

Germany set up a government for the colony, with its capital first at Buea and later at Yaoundé. They continued to explore the interior and either worked with or took over local rulers. The biggest conflicts were the Bafut Wars and the Adamawa Wars, which ended by 1907 with German victories.

Germany was very interested in Cameroon's farming potential. They gave large companies the job of using and exporting these resources. German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck said the priorities were: "first the merchant, then the soldier." A businessman named Adolph Woermann, whose company had a trading house in Douala, convinced Bismarck to support the colonial project. Large German trading companies (like Woermann and Jantzen & Thormählen) and concession companies (like Südkamerun Gesellschaft) set up many businesses in the colony. The government let these big companies run things, simply supporting them, protecting them, and trying to stop local rebellions.

The German government invested a lot in Cameroon's infrastructure, including many railways. One example is the 160-meter single-span railway bridge over the southern branch of the Sanaga River. However, the local people did not want to work on these projects. So, the Germans started a harsh system of forced labor, which was very unpopular. In fact, Jesko von Puttkamer was removed from his job as governor because of his bad actions towards the native Cameroonians. In 1911, after the Agadir Crisis, France gave nearly 300,000 square kilometers of French Equatorial Africa to Kamerun. This new area became Neukamerun (New Cameroon). In return, Germany gave a smaller area in northern Chad to France.

Soon after World War I began in 1914, the British invaded Cameroon from Nigeria, and the French invaded from French Equatorial Africa. This was part of the Kamerun campaign. The last German fort in the country surrendered in February 1916. After the Allies won, the territory was divided between the United Kingdom and France. This was made official on June 28, 1919, with League of Nations mandates. France got the larger part of the land. They gave Neukamerun back to neighboring French colonies and ruled the rest from Yaoundé as Cameroun (French Cameroons). Britain's territory was a strip bordering Nigeria from the sea to Lake Chad. It had about the same population and was ruled from Lagos as part of Nigeria, known as Cameroons (British Cameroons).

French Cameroon (1918-1960)

French Rule and UN Trust Territory

The French government did not give back much of the property in Cameroon to its former German owners. Instead, they gave much of it to French companies. This was especially true for the Société financière des Caoutchoucs, which got plantations that had been started during the German period. This company became the largest in French Cameroon. Roads and other building projects were done using local labor, often in very harsh conditions. The Douala-Yaoundé railway line, which the Germans had started, was completed. Thousands of workers were forced to work there for 54 hours a week. Workers also suffered from a lack of food and many mosquitoes, which caused illnesses. In 1925, the death rate at this site was 61.7%. However, other sites were not as deadly, even though working conditions were generally very tough.

French Cameroon joined the Free France movement in August 1940. The system set up by Free France was mostly a military dictatorship. Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque declared a state of emergency across the country and took away almost all public freedoms. The goal was to stop any thoughts of independence or sympathy for the former German colonizers. Local people who were known to like the Germans were executed in public places. In 1945, the country was placed under the supervision of the United Nations, which took over from the League of Nations. The UN left Cameroon under French control as a UN Trust Territory.

Road to Independence

In 1948, the Union des populations du Cameroun (UPC), a group that wanted independence, was founded. Ruben Um Nyobe became its leader. In May 1955, independence activists were arrested, which led to riots in several cities. The government's harsh response caused many deaths. The French government officially reported 22 deaths, but secret reports admitted many more. The UPC was banned, and nearly 800 of its activists were arrested. Many were beaten in prison. Because they were wanted by the police, UPC activists hid in the forests, where they formed small fighting groups. They also found safety in neighboring British Cameroon. The French authorities put down these events and made unfair arrests. The UPC received support from leaders like Gamal Abdel Nasser and Kwame Nkrumah. France's actions were criticized at the UN by countries like India, Syria, and the Soviet Union.

An uprising started among the Bassa people on December 18-19, 1956. Many people who were against the UPC were killed or kidnapped. Bridges, telephone lines, and other important structures were destroyed. The French military and local security forces violently stopped these uprisings. This led many native Cameroonians to join the fight for independence, starting a long-running guerilla war. Several UPC militias were formed, but they had very few weapons. Although the UPC was a movement of many ethnic groups, the pro-independence movement was especially strong among the Bamileke and Bassa peoples. Both groups were severely targeted by the French, who destroyed villages, forced people to move, and killed people without reason. This was sometimes called the Bamileke War or the Cameroon Independence War. Even though the uprising was put down, guerilla violence and revenge attacks continued even after independence.

Elections were held on December 23, 1956. The new Assembly passed a law on April 16, 1957, which made French Cameroon a state. It became an associated territory and a member of the French Union. Its people became Cameroonian citizens, and Cameroonian government bodies were created under a parliamentary democracy. On June 12, 1958, the Legislative Assembly of French Cameroon asked the French government to: "Grant independence to the State of Cameroon at the end of their trusteeship. Transfer all powers related to running Cameroon's internal affairs to Cameroonians." On October 19, 1958, France recognized the right of its United Nations trust territory to choose independence. On October 24, 1958, the Legislative Assembly of French Cameroon officially declared that Cameroonians wanted their country to become fully independent on January 1, 1960. It asked the French Cameroon government to tell the United Nations General Assembly to end the trusteeship agreement when French Cameroon became independent.

On November 12, 1958, France asked the United Nations to grant French Cameroon independence and end the Trusteeship. On December 5, 1958, the United Nations General Assembly noted France's statement that French Cameroon would gain independence on January 1, 1960. On March 13, 1959, the United Nations General Assembly decided that the UN Trusteeship Agreement with France for French Cameroon would end when French Cameroon became independent on January 1, 1960.

British Cameroons (1918-1961)

British Rule and Plebiscite

The British territory was managed as two areas: Northern Cameroons and Southern Cameroons. Northern Cameroons had two separate parts, divided by where the Nigerian and Cameroon borders met. These parts were governed as part of the Northern Region of Nigeria. Southern Cameroons was managed as a province of Eastern Nigeria. In British Cameroons, many German administrators were allowed to continue running the farms in the southern coastal area after World War I. A British report in 1922 said that the German farms there were "wonderful examples of industry, based on solid scientific knowledge." It also noted that "Natives have been taught discipline and have come to realize what can be achieved by industry." Many who returned to their villages started their own cocoa or other farms, which increased the country's wealth. In the 1930s, most of the white population were still Germans. Most of them were held in British camps starting in June 1940. The local population showed little interest in joining the British forces during World War II; only 3,500 men did so.

When the League of Nations ended in 1946, British Cameroons was reclassified as a UN trust territory. It was managed through the UN Trusteeship Council but remained under British control. The United Nations approved the agreements for British Cameroons to be governed by Britain on June 12, 1946.

French Cameroun became independent as Cameroon in January 1960. Nigeria was also set to become independent later that year. This raised the question of what would happen to the British territory. After some discussions, a vote called a plebiscite was held on February 11, 1961. The northern area, which was mostly Muslim, voted to join Nigeria. The southern area voted to join Cameroon.

Independence and Early Leaders (1960–1982)

French Cameroon became independent on January 1, 1960. It was the second French colony in Sub-Saharan Africa to gain independence, after Guinea. On February 21, 1960, the new nation held a vote to approve a new constitution. On May 5, 1960, Ahmadou Ahidjo became president. Ahidjo stayed very close to France. He allowed many French advisors and administrators to remain. He also left most of the country's businesses in the hands of French companies.

Joining Southern Cameroons

On February 12, 1961, the results of the Southern Cameroon vote were announced. Southern Cameroons had voted to join the Republic of Cameroon. This was sometimes called "reunification" because both regions had been part of German Kamerun before. To discuss how this union would work, the Foumban Conference was held from July 16-21, 1961. John Ngu Foncha, the leader of the Kamerun National Democratic Party and the elected government of Southern Cameroons, represented Southern Cameroons. Ahidjo represented Cameroon.

They agreed on a new constitution. It was largely based on the one adopted in Cameroon earlier that year. But it created a federal system, giving the former British Cameroons (now called West Cameroon) power over certain issues and legal rights. Buea became the capital of West Cameroon. Yaounde served as both the federal capital and the capital of East Cameroon. Neither side was completely happy. Ahidjo had wanted a single, more centralized state. The West Cameroonians had wanted more specific protections. On August 14, 1961, the federal constitution was adopted, with Ahidjo as president. Foncha became the prime minister of West Cameroon and vice president of the Federal Republic of Cameroon. The joining of British and French Cameroon has caused language and cultural problems in Cameroon, which has led to violence.

Civil War and Strong Rule

The UPC, which had wanted a complete break from France and many of whom believed in Marxist or other leftist ideas, were not happy with Ahidjo's rule and his close cooperation with the French. They did not stop fighting after independence. They tried to overthrow Ahidjo's government, which they saw as too loyal to France. Some, but not all, of them openly supported Marxist views. Ahidjo asked for continued French help to put down the UPC rebels. This conflict became known as the Bamileke War, named after the region where much of the fighting happened. The UPC was finally defeated when government forces captured the last important rebel leader in 1970.

During these years, Ahidjo used special powers given to him because of the war and the fear of more ethnic conflict. He used these powers to gather more control for himself. He set up a very centralized and strict government. This government used unfair police arrests, banned meetings and rallies, censored publications, limited freedom of movement with passes or curfews, and banned trade unions to prevent opposition. Anyone accused of "endangering public safety" was dealt with outside the normal legal process. They had no right to a lawyer or any appeal. Many people were sentenced to life in prison with hard labor or death, and executions were often public.

In 1966, opposition parties were banned, and Cameroon became a one-party state. On March 28, 1970, Ahidjo was re-elected president with 100% of the votes and 99.4% of people voting. Solomon Tandeng Muna became vice president. In 1972, a vote was held on a new constitution. This constitution replaced the federal system between East and West with a single state called the United Republic of Cameroon. It also gave the president even more power. Official results claimed 98.2% of people voted, and 99.99% voted in favor of the new constitution. Although Ahidjo's rule was strict, he was seen as less exciting than many other African leaders after colonial rule. He did not follow the anti-Western policies that many of these leaders did. This helped Cameroon have some political stability, keep Western investments, and see steady economic growth.

Oil Discovery

Cameroon started producing oil in 1977. The way oil money was handled was not clear at all. Many Cameroonians felt the money was badly managed or stolen. Oil is still a main part of the economy, though Cameroon does not rely on oil as much as some other oil-producing countries in the region.

Biya Era (1982–Present)

On June 30, 1975, Paul Biya, who had worked for a long time as an official in the Ahidjo government, was named Prime Minister. On November 4, 1982, Ahidjo resigned as president, and Biya became his legal successor. Many people were surprised because Biya is a Christian from the south, while Ahidjo was a Muslim from the north, and Ahidjo was only 59 years old. However, Ahidjo did not give up his role as leader of the ruling party. Many people thought he hoped Biya would be just a figurehead, or maybe even a temporary leader, as Ahidjo was rumored to be sick and getting medical care in France.

Conflict and Coup Attempt

Even though they had been on good terms before, in 1983, a disagreement became clear between Biya and Ahidjo. Ahidjo left for France and publicly accused Biya of misusing his power. Ahidjo tried to use his control over the party to push Biya aside. He wanted the party, not the President, to decide the government's plans. However, at the party meeting in September, Biya was elected to lead the party, and Ahidjo resigned. In January 1984, Biya was elected president of the country, running without any opponents. In February, two senior officials were arrested and tried. Ahidjo was tried in absentia (meaning he was not there) alongside them.

On April 6, 1984, supporters of Ahidjo tried to overthrow the government. This attempt was led by the Republican Guard, an elite military group recruited by Ahidjo, mostly from the north. The Republican Guard, under Colonel Saleh Ibrahim, took control of the Yaounde airport, the national radio station, and other important places around the capital. However, Biya was able to stay safe in the presidential palace with his bodyguards until troops from outside the capital could regain control within two days. Ahidjo denied knowing about or being responsible for the coup attempt, but many people believed he was behind it.

Lake Disasters

On August 15, 1984, Lake Monoun suddenly released a huge amount of carbon dioxide gas in what is called a limnic eruption. This gas caused 37 people to die by suffocation. On August 21, 1986, another limnic eruption at Lake Nyos killed as many as 1,800 people and 3,500 farm animals. These two disasters are the only recorded times that limnic eruptions have happened. However, evidence from rocks and soil shows they might have caused large local deaths before written history began.

Political Changes

Biya had first seemed to support relaxing rules on public life. But the coup attempt ended any signs of opening up. However, by 1990, Western governments were putting more pressure on Cameroon. The end of the Cold War made them less willing to tolerate strict governments that were their allies. In December 1990, opposition parties were allowed for the first time since 1966. The first elections with multiple parties were held in 1992 and were very close. Biya won with 40% of the vote, while his closest opponent got 36%, and another opposition party got 19%. In Parliament, Biya's ruling party won the most votes with 45% but did not get a majority. Biya did not like how close the election was. Later elections have been widely criticized by opposition parties and international observers as unfair, with many problems. The ruling party has since had no trouble winning large majorities.

Pressure from English-speaking groups in the former British Cameroons led to changes in the constitution in 1996. These changes were supposed to spread power out, but they did not meet the demands of the English-speakers to bring back the federal system. Because of continued opposition, many of the changes adopted in 1996 have never been fully put into practice. Power remains very centralized with the President.

Bakassi Border Conflict

Bakassi is a piece of land shaped like a finger, located on the Gulf of Guinea. It lies between the Cross River estuary and the Rio del Rey estuary to the east. Nigeria managed this area during the colonial period. However, after independence, efforts to mark the border showed that a 1913 agreement between Britain and Germany placed Bakassi in German Cameroon. This meant it should belong to Cameroon. Nigeria pointed to other colonial-era documents and agreements, and their long history of managing the area, to disagree with this idea. The competing claims became serious after oil was found in the region. An agreement between the two countries in 1975 was stopped by a coup in Nigeria. In 1981, fights between Nigerian and Cameroonian forces resulted in several deaths and almost led to a war between the two nations. The border saw more clashes several times throughout the 1980s. In 1993, the situation got worse, with both countries sending many soldiers to the region and many reports of small fights and attacks against civilians. On March 29, 1994, Cameroon took the issue to the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

In October 2002, the International Court of Justice ruled in favor of Cameroon. However, Nigeria resisted this ruling. Pressure from the UN and other countries, and the threat of losing foreign aid, finally forced Nigeria to agree. In 2006, the Greentree Agreement set out a plan for the area to be transferred over two years. The transfer was successful. But many people living on the peninsula kept their Nigerian citizenship and are still unhappy with the change. Small-scale violence continued until it became part of the Anglophone Crisis in 2017.

2008 Protests

In February 2008, Cameroon experienced widespread violent unrest. A strike by transport workers, who were protesting high fuel prices and bad working conditions, happened at the same time as President Paul Biya announced he wanted to change the constitution to remove term limits. Biya was supposed to leave power at the end of his term in 2011. After several days of widespread riots, looting, and reports of gunfire in all the major cities, calm was eventually restored after a crackdown. Thousands were arrested, and at least several dozen people were killed. The government announced lower fuel prices, increased wages for the military and government workers, and lowered taxes on key foods and building materials. Many opposition groups reported more harassment and limits on speech, gatherings, and political activity after the protests. In the end, the constitutional term limits were removed, and Biya was reelected in 2011. This election was criticized by the opposition and international observers as having many problems and low voter turnout.

Current Issues

Boko Haram Insurgency

In 2014, the Boko Haram insurgency spread into Cameroon from Nigeria. In May 2014, after the Chibok schoolgirl kidnapping, Presidents Paul Biya of Cameroon and Idriss Déby of Chad announced they were fighting Boko Haram. They sent troops to the Northern Nigerian border. Cameroon announced in September 2018 that Boko Haram had been pushed back. However, the conflict continues in the northern border areas.

Anglophone Crisis

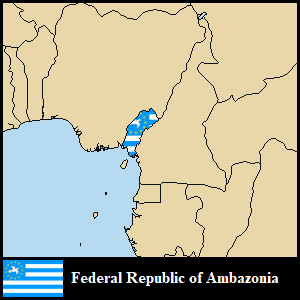

In November 2016, major protests broke out in the English-speaking regions of Cameroon. In September 2017, the protests and the government's response grew into an armed conflict. Separatists declared the independence of Ambazonia and started a guerilla war against the Cameroonian Army.

Football Success

Cameroon has gained some international attention because of the success of its football team. The team has qualified for the FIFA World Cup eight times, which is more than any other African team. However, the team has only made it past the group stage once, in 1990. That year, they became the first African team to reach the quarter-final of the World Cup. They have also won the Africa Cup of Nations five times.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Camerún para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Camerún para niños

- Ambazonia

- History of Africa

- Politics of Cameroon

- List of heads of government of Cameroon

- List of heads of state of Cameroon

- Douala history and timeline

- Yaoundé history and timeline

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |