History of Iceland facts for kids

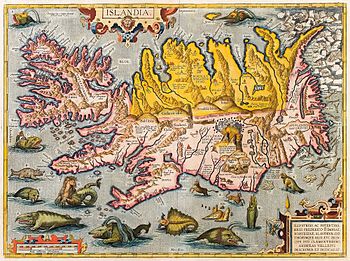

The story of Iceland began when Vikings and people they brought from places like Norway and the British Isles settled there in the late 800s. Before that, Iceland was empty, even though other parts of Western Europe had been settled for a long time. Most people say the first settlers arrived in 874. However, some old stories (called sagas) say that Irish monks, known as papar, might have lived in Iceland even earlier.

The land was settled very quickly. Many Norwegians came, perhaps to escape fighting or to find new land for farming. By 930, the leaders had created a special meeting called the Althing. This makes it one of the oldest parliaments in the world! Around the late 900s, Christianity came to Iceland, influenced by the Norwegian king Olaf Tryggvason. During this time, Iceland was independent, a period known as the Old Commonwealth. Icelandic historians started writing down their nation's history in books called sagas of Icelanders.

In the early 1200s, a time of fighting called the age of the Sturlungs made Iceland weak. Because of this, Iceland eventually came under the rule of Norway. This change was made official with agreements like the Old Covenant (1262–1264). Norway later joined with Sweden and then Denmark. Eventually, all the Nordic countries formed one big group called the Kalmar Union. When this union ended, Iceland became part of Denmark.

A strict Danish–Icelandic Trade Monopoly in the 1600s and 1700s hurt Iceland's economy. The country became very poor, and this was made worse by terrible natural disasters, like the Móðuharðindin or "Mist Hardships." Many people died during this time.

Iceland stayed part of Denmark for a long time. But in the 1800s, people across Europe started wanting their own independent nations. Iceland also began an independence movement. The Althing, which had been stopped in 1799, was brought back in 1844. Iceland finally became a sovereign (self-governing) country after World War I, forming the Kingdom of Iceland on December 1, 1918. However, Iceland still shared the Danish King until World War II.

Even though Iceland was neutral in World War II, the United Kingdom peacefully took control of it in 1940. This was to stop Nazi Germany from taking over after they invaded Denmark. Because Iceland was in an important spot in the North Atlantic, the Allies (like the UK and later the US) stayed there until the war ended. The United States took over from the British in 1941. In 1944, Iceland officially broke its ties with Denmark (which was still under Nazi rule) and became a republic.

After World War II, Iceland helped start the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and joined the United Nations. Its economy grew fast, mostly thanks to fishing, even though this led to arguments with other countries.

Vigdis Finnbogadottir became Iceland's president on August 1, 1980. She was the third woman in the world to be elected as a head of state.

After a period of fast economic growth, Iceland faced a big financial crisis from 2008 to 2011. Today, Iceland is still not part of the European Union.

Iceland is very far away from other countries. This meant it was mostly safe from European wars. But it was still affected by other big events, like the Black Death (a terrible sickness) and the Protestant Reformation, which Denmark made Iceland adopt. Iceland's history has also seen many natural disasters.

Iceland is a young island in terms of geology. It formed about 20 million years ago from volcanoes erupting along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. It's still growing today from new volcanic activity. The oldest rocks found in Iceland are about c. 16 million years old.

Contents

Iceland's Geological Beginnings

Iceland is a very young island geologically. It started to form about 20 million years ago during the Miocene era. This happened because of many volcanic eruptions on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This ridge is where the North American and Eurasian plates are slowly moving apart, about 2.5 centimeters each year.

The volcanic activity in Iceland is caused by a "hotspot." This is a super hot area deep inside the Earth's mantle that helps create and keep the island growing. For example, the Faroe Islands are much older, about 55 million years old. The younger rocks in southwest Iceland and the central highlands are only about 700,000 years old.

Earth's history is divided into ice ages based on temperature. The last major ice age started about 110,000 years ago and ended around 10,000 years ago. During this time, Iceland was covered in ice, which helped shape its icefalls, fjords, and valleys.

Early Human Presence in Iceland

For a long time, Iceland was one of the last large islands in the world without people. Some people thought the ancient Greek geographer Pytheas might have been talking about Iceland when he mentioned a land called Thule. But Pytheas described it as a farming country with lots of milk, honey, and fruit, which doesn't sound like early Iceland. It was probably Norway, or maybe the Faroe Islands or Shetland.

Many early settlers in Iceland were from a part of Norway called Telemark. They were escaping the rule of King Harald Fairhair, who was uniting Norway. We don't know the exact date humans first arrived. Some old Roman coins have been found in Iceland, but we don't know if they arrived with early visitors or much later with Vikings.

Irish Monks: Early Visitors?

There are some old writings that suggest monks from Ireland and Scotland might have lived in Iceland before the Norse people arrived. The Landnámabók ("Book of Settlements"), written in the 1100s, talks about Irish monks called the Papar. It says they left behind Irish books, bells, and other items. According to this book, the monks either left before the Norse arrived or when they saw them coming.

Another old book, Íslendingabók, written between 1122 and 1133, also mentions these Irish monks. It says they left because they didn't want to live with the pagan Norsemen. These monks might have been part of a group that spread Christianity in the Middle Ages, or they might have been hermits (people who live alone for religious reasons).

Recently, archaeologists found the remains of a small house in Hafnir, near Keflavík International Airport. Carbon dating shows that this house was left sometime between 770 and 880. This suggests that people were in Iceland before 874, which is the usual date for Norse settlement. This finding might also mean the monks left Iceland before the Norse arrived.

Norse Discoveries

According to the Landnámabók, Iceland was first discovered by Naddodd. He was sailing from Norway to the Faroe Islands but got lost and ended up on Iceland's east coast. Naddodd called the country Snæland, meaning "Snowland."

Another Swedish sailor, Garðar Svavarsson, also accidentally drifted to Iceland. He realized it was an island and called it Garðarshólmi ("Garðar's Islet"). He stayed for the winter in Húsavík.

The first Norseman who purposely sailed to Garðarshólmi was Hrafna-Flóki Vilgerðarson. Flóki stayed for one winter in Barðaströnd. After a very cold winter, summer came, and the whole island turned green, which amazed Flóki. He realized that despite the harsh winter, this place could be lived in and had useful resources. He then sailed back to Norway with supplies and new knowledge.

Settling Iceland (874–930)

The first person to permanently settle in Iceland is usually thought to be a Norwegian leader named Ingólfr Arnarson and his wife, Hallveig Fróðadóttir. The Landnámabók says that as he got close to land, he threw two carved pillars (called Öndvegissúlur) overboard. He promised to settle wherever they landed. He then sailed along the coast until the pillars were found in the southwest, in an area now called Reykjanesskagi.

He settled there with his family around 874. He named the place Reykjavík, meaning "Smoke Cove," probably because of the steam rising from the hot springs. This place later became the capital and largest city of modern Iceland. However, it's possible that Ingólfr Arnarson wasn't the very first permanent settler. That might have been Náttfari, one of Garðar Svavarsson's men who stayed behind.

Most of what we know about Ingólfr comes from the Landnámabók, which was written about 300 years after the settlement. But archaeological discoveries in Reykjavík match the date given in the book, showing there was a settlement there around 870.

According to the Landnámabók, many more Norse leaders, their families, and their servants followed Ingólfr. They settled all the parts of the island where people could live in the following decades. Archaeological evidence strongly suggests that this timeline is correct: "the whole country was occupied within a couple of decades towards the end of the 9th century."

These settlers mainly came from Norway, Ireland, and Scotland. The sagas and other old documents say that some of the Irish and Scots were servants or enslaved people of the Norse chiefs. Some settlers from the British Isles were "Norse–Gaels," meaning they had family and cultural ties to both Norway and the coastal areas of Ireland or Scotland.

The common reason given for people leaving Norway is that they were escaping the harsh rule of King Harald Fairhair. Medieval writings say he united parts of Norway during this time. Viking raids into Britain were also stopped around this time, which might have made people look for peaceful places to settle. It's also thought that the western fjords of Norway were simply too crowded.

The settlement of Iceland is well-recorded in the Landnámabók. However, this book was put together in the early 1100s, so it was written at least 200 years after the settlement period. Íslendingabók by Ari Þorgilsson is generally seen as more accurate and is probably a bit older, but it's not as detailed. It does say that Iceland was fully settled within 60 years, which likely means all the good farming land was claimed by settlers.

The Icelandic Commonwealth (930–1262)

Quick facts for kids

Norwegian Iceland

Norska Ísland (Icelandic)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1262–1814 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Common languages | Icelandic | ||||||||

| Religion | 1262–1814 Catholic |

||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Established

|

1262 | ||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

1814 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

In 930, the ruling leaders set up a big meeting called the Alþingi (Althing). This parliament met every summer at Þingvellir. Here, important leaders (called Goðar) changed laws, settled arguments, and chose groups of people to judge lawsuits. Laws were not written down. Instead, an elected Lawspeaker (lǫgsǫgumaðr) memorized them. The Alþingi is sometimes called the oldest existing parliament in the world.

It's important to know that there was no strong central government. Laws were only enforced by the people themselves. This led to many arguments and fights between families, which gave the saga writers lots of stories to tell!

Iceland had a time of mostly steady growth during its commonwealth years. Settlements from that time have been found in southwest Greenland and eastern Canada. Sagas like Saga of Erik the Red and Greenland saga tell about the adventures of these settlers.

|

Danish Iceland

Danska Ísland (Icelandic)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1524–1945 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Common languages | Icelandic | ||||||||

| Religion | 1524–1550 Catholic 1550–1945 Lutheran |

||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Icelandic | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Established

|

1524 | ||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

1945 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

The Spread of Christianity

The first settlers in Iceland mostly followed pagan religions, worshiping Norse gods like Odin, Thor, Freyr, and Freyja. By the 900s, there was pressure from Europe for Iceland to become Christian. As the year 1000 got closer, many important Icelanders had accepted the new faith.

In the year 1000, it looked like there might be a civil war between the different religious groups. So, the Alþingi chose a chieftain named Thorgeir Ljosvetningagodi to decide the issue of religion. He decided that the whole country should become Christian. However, pagans would still be allowed to worship their old gods in private.

The first Icelandic bishop, Ísleifur Gissurarson, was made a bishop in 1056.

Civil War and the End of Independence

During the 1000s and 1100s, power in Iceland started to become more centralized. The independence that local farmers and chieftains once had slowly disappeared. A few powerful families and their leaders gained more and more control.

The period from about 1200 to 1262 is known as the Age of the Sturlungs. This refers to Sturla Þórðarson and his sons, Sighvatr Sturluson and Snorri Sturluson. They were one of two main family groups fighting for power over Iceland. This caused a lot of trouble in a land mostly lived in by farmers, who could not easily leave their farms to fight for their leaders.

In 1220, Snorri Sturluson became a vassal (a person who owes loyalty and service) to Haakon IV of Norway. His nephew, Sturla Sighvatsson, also became a vassal in 1235. Sturla used his family's power to fight against other family groups in Iceland. The Norwegian king's power over Iceland grew throughout the 1200s.

After many years of fighting, the Icelandic chieftains agreed to accept the rule of Norway. They signed the Old Covenant (Gamli sáttmáli), which created a union with the Norwegian monarchy. The end of Iceland's independence is usually marked by the signing of the Old Covenant (1262–1264) or when a new law book, Jónsbók, was adopted in 1281.

Iceland Under Norwegian and Danish Kings (1262–1944)

Norwegian Rule

Not much changed right after Iceland joined Norway. Norway slowly gained more control, and the Althing tried to keep its power to make and judge laws. However, Christian church leaders had special chances to get rich through taxes (called tithes). So, power slowly moved to the church leaders as Iceland's two bishops gained land from the old chieftains.

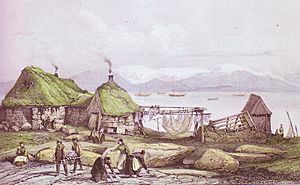

Around the time Iceland became part of Norway, the climate changed. This is now called the Little Ice Age. Areas near the Arctic Circle, like Iceland and Greenland, started having shorter growing seasons and colder winters. Since Iceland already had poor farmland, this climate change made life very hard for the people. A system called the vistarband developed, where farmers had to work for landowners for a year at a time.

It became harder to grow barley, which was the main grain crop. Livestock needed more food to survive the longer, colder winters. Icelanders started trading for grain from Europe, which was expensive. Church rules about fasting increased the demand for dried codfish. Cod was easy to catch and prepare for export, so the cod trade became a very important part of the economy.

The Kalmar Union

Iceland remained under Norwegian kings until 1380. Then, the Norwegian royal family died out. Norway (and so Iceland) became part of the Kalmar Union, along with Sweden and Denmark. Denmark was the most powerful country in this union. Unlike Norway, Denmark didn't need Iceland's fish and wool. This caused a big problem for Iceland's trade. The small Viking settlement in Greenland, started in the late 900s, completely disappeared before 1500.

In 1660, Frederick III of Denmark introduced absolute monarchy in Denmark-Norway. This meant the king had all the power. Icelanders gave up their right to make their own laws to the king. However, Denmark didn't protect Iceland very well. In 1627, Barbary pirates attacked Iceland and took almost 300 Icelanders as slaves. This event is known as the Turkish Abductions.

After the Kalmar Union ended, the Danish government took more control over Iceland. They especially worked to stop English traders from doing business with Iceland.

Foreign Traders and Fishermen

English and German traders became more common in Iceland in the early 1400s. Some historians call the 1400s the "English Age" in Iceland because of how many English traders and fishing fleets were there. Foreigners came to Iceland mainly to fish in the rich waters off its coast. Trade with Iceland was important for some British ports. For example, in Hull, trade with Iceland made up more than ten percent of all its trade. This trade is believed to have improved living standards in Iceland.

The 1500s are sometimes called the "German Age" by Icelandic historians because of how important German traders were. The Germans didn't do much fishing themselves. Instead, they owned fishing boats, rented them to Icelanders, and then bought the fish from Icelandic fishermen to sell in Europe.

Even after the Danes started a trade monopoly, some illegal trade continued with foreigners. Dutch and French traders became more common in the mid-1600s.

The Reformation and Danish Trade Rules

By the mid-1500s, Christian III of Denmark started making his people become Lutherans. Jón Arason and Ögmundur Pálsson, who were Catholic bishops in Iceland, were against Christian's efforts to bring the Protestant Reformation to Iceland. Ögmundur was sent away by Danish officials in 1541, but Jón Arason fought back.

The opposition to the Reformation ended in 1550 when Jón Arason was captured after losing a battle. Jón Arason and his two sons were then executed. After this, Icelanders became Lutherans, and most still are today.

In 1602, the Danish government ordered that Iceland could only trade with Denmark. This was part of Denmark's plan to control trade and make money. The Danish–Icelandic Trade Monopoly lasted until 1786.

The Laki Eruption

In the 1700s, the weather in Iceland became the worst it had been since the first settlers arrived. On top of this, the Laki volcano erupted in 1783. It spewed out a huge amount of lava. Floods, ash, and poisonous fumes killed 9,000 people and 80% of the farm animals. The starvation that followed killed a quarter of Iceland's population. This terrible time is known as the Móðuharðindin or "Mist Hardships."

Danish Control of Iceland

When Denmark and Norway were separated by the Treaty of Kiel in 1814, after the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark kept Iceland, along with the Faroe Islands and Greenland, as its territories.

The Push for Independence

Throughout the 1800s, Iceland's climate continued to get worse. This led to many people moving away, especially to Manitoba in Canada. However, a new feeling of national pride grew in Iceland. This was inspired by ideas from Europe about romantic nationalism. This movement was led by the Fjölnismenn, a group of Icelandic thinkers who had studied in Denmark.

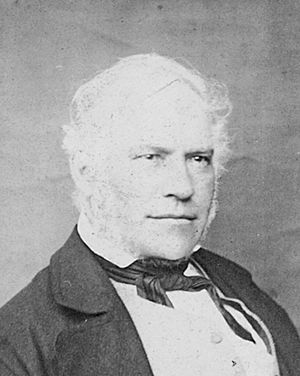

An independence movement grew under the leadership of a lawyer named Jón Sigurðsson. In 1843, a new Althing was created as a group that could advise the government. It said it was a continuation of the old Althing from the Icelandic Commonwealth, which had been a court for centuries and was stopped in 1800.

Self-Rule and Sovereignty

In 1874, a thousand years after the first known settlement, Denmark gave Iceland its own constitution and some self-rule. This self-rule was expanded in 1904. The constitution was changed in 1903, and a minister for Icelandic affairs, who lived in Reykjavík, became responsible to the Althing. Hannes Hafstein was the first person to hold this job.

The Danish–Icelandic Act of Union, signed by Iceland and Denmark on December 1, 1918, recognized Iceland as a fully independent country—the Kingdom of Iceland. It was joined with Denmark only through having the same king. Iceland got its own flag. Denmark was supposed to handle Iceland's foreign affairs and defense. Iceland had no military, and Denmark was to tell other countries that Iceland would always be neutral. The agreement was supposed to be reviewed in 1940 and could be ended three years later if no new agreement was reached. By the 1930s, most people in Iceland wanted complete independence by 1944 at the latest.

World War I's Impact

In the 25 years before World War I, Iceland had done well. However, during World War I, Iceland became more isolated and living standards dropped a lot. The government went into debt, and there was a shortage of food, with fears of a famine.

Iceland was part of neutral Denmark during the war. Icelanders generally supported the Allies (like Britain and France). Iceland also traded a lot with the United Kingdom during the war. To stop Iceland from trading with Germany indirectly, the British put strict and time-consuming rules on Icelandic goods going to Nordic countries. There is no sign that Germany planned to invade Iceland during the war.

About 1,245 Icelanders, Icelandic Americans, and Icelandic Canadians fought as soldiers in World War I. Most fought for Canada or the United States. 391 of these soldiers were born in Iceland. At least 144 of them died during the war.

The war had a lasting effect on Iceland. It led to the government getting much more involved in the economy, which continued after World War II. Iceland's ability to manage its own affairs and deal with other countries during the war, when its connection with Denmark was interrupted, showed that it could handle more power. This led to Denmark recognizing Iceland as a fully independent country in 1918. Some say that the desire for war news helped the newspaper Morgunblaðið become very popular in Iceland.

The Great Depression's Effects

Iceland's good times after World War I ended when the Great Depression began. This was a very bad economic crash that affected the whole world. The depression hit Iceland hard as the value of its exports fell sharply. The total value of Icelandic exports dropped from 74 million kronur in 1929 to 48 million kronur in 1932. It didn't return to the pre-1930 level until after 1939.

The government became more involved in the economy: "Imports were controlled, foreign money trade was controlled by state-owned banks, and loans were mostly given out by state-regulated funds." The start of the Spanish Civil War cut Iceland's exports of dried salted fish by half. The depression lasted in Iceland until World War II began, when prices for fish exports went up a lot.

World War II and Occupation

As war approached in spring 1939, Iceland realized its exposed location would be very dangerous. A government with all political parties was formed. A request from Lufthansa (a German airline) for civilian plane landing rights was turned down. German ships were common until the British blocked Germany when the war started in September. Iceland asked Britain to allow it to trade with Germany, but this was not allowed.

The occupation of Denmark by Nazi Germany began on April 9, 1940. This cut off communication between Iceland and Denmark. So, on April 10, the Parliament of Iceland temporarily took control of foreign affairs (creating what would become the Ministry for Foreign Affairs) and the Coast Guard. Parliament also chose a temporary governor, Sveinn Björnsson, who later became the first president of the Republic. With these actions, Iceland became truly self-governing. At the time, Icelanders and the Danish King thought this situation was temporary. They believed Iceland would give these powers back to Denmark when the occupation was over.

Iceland turned down British offers of protection after Denmark was occupied because it would go against Iceland's neutrality. Britain and the U.S. started direct diplomatic relations, as did Sweden and Norway. Germany's takeover of Norway left Iceland very vulnerable. Britain decided it couldn't risk Germany taking over Iceland.

On May 10, 1940, British military forces began an invasion of Iceland when they sailed into Reykjavík harbor in Operation Fork. There was no fighting, but the government protested, calling it a "clear violation" of Icelandic neutrality. However, Prime Minister Hermann Jónasson asked Icelanders to treat the British troops politely, as if they were guests. They did, and there were no problems. The occupation of Iceland lasted throughout the war.

At its peak, the British had 25,000 troops in Iceland. This almost completely ended unemployment in the Reykjavík area and other important places. In July 1941, the United States took over responsibility for Iceland's occupation and defense. This was part of a U.S.-Icelandic agreement that said the U.S. would recognize Iceland's complete independence. The British were replaced by up to 40,000 Americans, who outnumbered all adult Icelandic men. (At the time, Iceland had about 120,000 people.)

About 159 Icelanders are confirmed to have died in World War II fighting. Most were killed on cargo and fishing boats sunk by German planes, submarines, or mines. Another 70 Icelanders died at sea, but it's not confirmed if they died because of the war.

The occupation of Iceland by the British and Americans brought a huge economic boost. The occupying forces put a lot of money into the Icelandic economy and started many projects. This ended unemployment in Iceland and greatly increased wages. One study says that "by the end of World War II, Iceland had been transformed from one of Europe’s poorest countries to one of the world’s wealthiest."

The Republic of Iceland (1944–Present)

Founding the Republic

On December 31, 1943, the Act of Union agreement with Denmark ended after 25 years. Starting on May 20, 1944, Icelanders voted for four days on whether to end the union with the King of Denmark and create a republic. The vote was 97% in favor of ending the union and 95% in favor of the new republican constitution. Iceland became an independent republic on June 17, 1944, with Sveinn Björnsson as its first president. Denmark was still occupied by Germany at the time. Danish King Christian X sent a message of congratulations to the Icelandic people.

Iceland had done very well during the war, saving a lot of money in foreign banks. Also, the country received the most Marshall Aid per person of any European country right after the war.

The new government, made up of a mix of parties, decided to use these funds to fix up the fishing fleet, build fish processing factories, create a cement and fertilizer factory, and generally modernize farming. These actions aimed to keep Icelanders' standard of living as high as it had been during the prosperous war years.

The government's economic plan was to create the necessary industries for a rich, developed country. It was important to keep unemployment low and protect the fishing industry through controlling money and other ways. Because Iceland depended so much on good fish catches and foreign demand for fish, its economy remained unstable until the 1990s, when the country's economy became much more diverse.

NATO, US Defense, and the Cold War

In October 1946, the Icelandic and United States governments agreed to end U.S. responsibility for Iceland's defense. However, the United States kept certain rights at Keflavík. This included the right to bring back a military presence if war threatened.

Iceland became a founding member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on March 30, 1949. It joined with the condition that it would never take part in attacking another nation. This membership came during an anti-NATO protest in Iceland. After the Korean War started in 1950, and because NATO military leaders asked, the United States and Iceland agreed that the United States should again be responsible for Iceland's defense. This agreement, signed on May 5, 1951, allowed the U.S. military to be in Iceland, which was sometimes controversial. The U.S. military stayed until 2006.

The U.S. base was important for transporting goods and communicating with Europe. It was a key part of watching Soviet submarine activity and an early warning system for incoming Soviet attacks. Even though U.S. forces are no longer permanently in Iceland, the U.S. still helps with the country's defense through NATO. Iceland has kept strong ties with other Nordic countries. Because of this, Norway, Denmark, Germany, and other European nations have increased their defense and rescue cooperation with Iceland since the U.S. forces left.

A 2018 study said that Iceland greatly benefited from its relationship with the United States during the Cold War. The United States gave a lot of economic help, supported Iceland in international groups, allowed Iceland to break some international rules, and helped Iceland win the Cod Wars. Despite this, the relationship with the United States was often debated in Icelandic politics. Some scholars called Iceland a "rebellious ally." Iceland often threatened to leave NATO or end the U.S. defense agreement during the Cold War. This is one reason why the United States went to great lengths to keep Iceland happy.

The Cod Wars

The Cod Wars were a series of disputes between Iceland and the United Kingdom from the 1950s to the mid-1970s. These conflicts were about fishing rights.

- The first dispute (1952–1956) was about Iceland extending its fishing limits from 3 to 4 nautical miles.

- The First Cod War (1958–1961) was fought over Iceland extending its limits from 4 to 12 nautical miles (7 to 22 km).

- The Second Cod War (1972–1973) happened when Iceland extended the limits to 50 miles (93 km).

- The Third Cod War (1975–1976) was fought over Iceland extending its fishing limits to 200 miles (370 km).

Icelandic patrol ships and British fishing boats clashed in all four conflicts. The Royal Navy was sent to the disputed waters in the last three Cod Wars, leading to well-known clashes.

During these arguments, Iceland threatened to close the U.S. base at Keflavík and leave NATO. Because of Iceland's important location during the Cold War, it was crucial for the U.S. and NATO to keep the base in Iceland and keep Iceland as a NATO member. While the Icelandic government did break off diplomatic relations with the UK during the Third Cod War, it never actually closed the U.S. base or left NATO.

It's unusual for such big and intense disputes to happen between two democracies like Iceland and the UK, which have close economic, cultural, and institutional ties.

Economic Changes and European Ties

In 1991, the Independence Party, led by Davíð Oddsson, formed a government with the Social Democrats. This government started policies to make the economy more open, selling off several state-owned companies. Iceland then became a member of the European Economic Area in 1994. The economy became more stable, and high inflation was greatly reduced.

In 1995, the Independence Party formed a new government with the Progressive Party. This government continued with free market policies, selling two commercial banks and the state-owned telecom company Landssíminn. Company income tax was lowered to 18% (from about 50% at the start of the decade). Inheritance tax was greatly reduced, and a tax on wealth was removed. A system for fishing quotas, first started in the late 1970s, was further developed.

This government stayed in power after elections in 1999 and 2003. In 2004, Davíð Oddsson stepped down as Prime Minister after 13 years. He was Iceland’s longest-serving Prime Minister. Halldór Ásgrímsson, leader of the Progressive Party, became prime minister from 2004 to 2006, followed by Geir H. Haarde.

After a small economic downturn in the early 1990s, the economy grew a lot, about 4% each year from 1994. The governments of the 1990s and 2000s followed a strong pro-U.S. foreign policy. They supported NATO's actions in the Kosovo War and joined the "Coalition of the willing" during the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

In March 2006, the United States announced it would remove most of its military forces from Iceland. On August 12, 2006, the last four F-15 fighter jets left Iceland. The United States closed the Keflavík Air Base in September 2006. In 2016, it was reported that the United States was thinking about reopening the base.

After elections in May 2007, the Independence Party, led by Haarde, stayed in government, but with a new group called the Social Democratic Alliance.

The Financial Crisis

In October 2008, the Icelandic banking system collapsed. This made Iceland ask for large loans from the International Monetary Fund and friendly countries. Many protests in late 2008 and early 2009 led to the Haarde government resigning. It was replaced on February 1, 2009, by a new government led by the Social Democratic Alliance and the Left-Green Movement. Social Democrat minister Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir became Prime Minister. Elections were held in April 2009, and the same government was formed again in May 2009.

The financial crisis also led to the Icesave dispute. This was an argument between Iceland and the United Kingdom and Netherlands about whether Iceland had to pay back British and Dutch people who lost their savings when the Icesave bank failed.

The crisis caused the largest number of people to leave Iceland since 1887, with 5,000 people moving away in 2009.

Iceland Since 2012

Iceland's economy became stable under the government of Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir, and it grew by 1.6% in 2012. However, many Icelanders were still unhappy with the economy and government spending cuts. The center-right Independence Party returned to power, working with the Progressive Party, in the 2013 elections.

In September 2017, the government led by Prime Minister Bjarni Benediktsson (leader of the Independence Party) fell apart after a small party left the government. However, the ruling parties lost their majority after a close 2017 election. On November 30, 2017, Katrín Jakobsdóttir became Iceland's new prime minister, even though her party came second in the election.

On August 1, 2016, Guðni Th. Jóhannesson became the new president of Iceland. He was re-elected by a huge number of votes in the 2020 presidential election.

After the 2021 parliamentary election, the new government was again a group of three parties: the Independence Party, the Progressive Party, and the Left-Green Movement. It was led by Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Islandia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Islandia para niños

- Military history of Iceland

- Politics of Iceland

- President of Iceland

- Prime Minister of Iceland

- Timeline of Icelandic history

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |