History of early modern Italy facts for kids

The history of early modern Italy covers the time from the Italian Renaissance up to the year 1814. This period ended with the Congress of Vienna. After this, Italy faced many political and social problems. These problems eventually led to the unification of Italy, which happened in 1861. That's when the Kingdom of Italy was officially created.

Contents

Italy's Journey: From Riches to Challenges

The Italian Renaissance was a golden age for Italy. It happened during the 15th and 16th centuries. This time brought huge growth in both money and culture. But after the year 1600, Italy's economy started to slow down. In 1600, northern and central Italy were very advanced. They had a high standard of living. By 1814, Italy was not doing well economically. Its factories and businesses had almost disappeared. There were too many people for the available resources. The economy became mostly about farming. Wars, political divisions, and changes in world trade routes caused these problems. Trade moved away from the Mediterranean Sea towards north-western Europe and the Americas.

Major Powers in Italy

After the Peace of Cateau Cambrésis in 1559, France gave up its claims in Italy. Some Italian states were ruled by powerful families. These included the Medici in Tuscany, the Farnese in Parma, and the Este in Modena. The Savoy family ruled in Piedmont. Almost half of Italy was under the control of the Spanish Empire. This included the kingdoms of Naples, Sicily, Sardinia, and the Duchy of Milan.

Piedmont was returned to the Savoy family from France. This happened because Duke Emmanuel Philibert played a key role. He helped win the Battle of St. Quentin during the Italian War of 1551–1559. The House of Savoy became more "Italian" after these wars. Emmanuel Philibert made Turin the capital of the savoyard state. He also made Italian the official language. The House of Medici continued to rule Florence. This was thanks to an agreement between the Pope and Charles V in 1530. Later, Pope Pius V recognized them as rulers of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. This same Pope also created the Holy League. This group included Venice and other sea powers. They defeated the Ottoman forces at the naval battle of Lepanto in 1571.

The Counter-Reformation and Its Impact

The Papal States led the Counter-Reformation. This period lasted from the Council of Trent (1545–1563) to the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. This time also saw many European wars of religion. Many Italians became important figures in other Catholic countries. Some even became unofficial rulers of France, like Catherine de Medici and Jules Mazarin. Others were military leaders for the Holy Roman Empire or Spain. These included Ambrogio Spinola and Alexander Farnese.

Despite their victory at Lepanto, the Venetians slowly lost their lands in the eastern Mediterranean. They lost Cyprus and Crete to the Ottomans. Venice did capture the Peloponnese during the Great Turkish war (1683–1699). But this land was given back after the last Venetian-Ottoman Wars. By the time the Seven Years' War began, Venice was no longer a major power. The same was true for its rivals, like the Ottoman Empire and the Genoese. Genoa had lost its lands in the Aegean Sea, Tunisia, and later, Corsica. Genoa's decline also affected Spain. Genoa had been a key ally of the Spanish Empire since the 16th century. It provided money and support to the Spanish rulers.

Shifting Powers and New Kingdoms

The War of the Spanish succession (1702–1715) and the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718–1720) changed things. The Habsburg monarchy became the main power in much of Lombardy and Southern Italy. However, the War of the Polish Succession brought the Spanish back to the south. In this time, Victor Amadeus II of Savoy and Eugene of Savoy defeated French and Spanish forces. This happened during the Siege of Turin in 1706. Later, Victor Amadeus II formed the kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. This state was a key step towards a united Italy. The Habsburg-Lorraine family took over from the Medici in Florence in 1737. Venice also became part of Austria with the treaty of Campo Formio in 1797.

Napoleon's Influence on Italy

The Napoleonic era connects the time of Habsburg rule to the Risorgimento. Napoleon had his first military successes in Italy. He led the Armée d'Italie. Later, he called himself President of Italy and King of Italy. Italy came under French influence. But many Italian thinkers liked Napoleon because of his Italian background. The writer Alessandro Manzoni was one of them. The return of the old rulers after Napoleon's defeat could not erase the new laws and ideas he brought to Italy.

Italy from the 16th to 18th Centuries

The Italian Wars saw France attack Italian states for 65 years. This started with Charles VIII's invasion of Naples in 1494. But the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559) put about half of Italy under Spanish rule. This included the south and Milan. The Austrian Habsburgs replaced them after the War of the Spanish Succession in 1700. The Council of Italy in Madrid controlled the Spanish lands in Italy. A special part of the Aulic council in Vienna ruled over the Imperial lands in Italy. Italian soldiers fought across Europe for the Catholic side. They fought in Germany, France, Italy, and the Spanish Netherlands. They also served in North Africa and on ships, including the Invincible Armada in 1588. They had good results in these battles. The War of the Spanish Succession moved control of Naples and Sicily from Spain to Austria. This happened with the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. However, the Spanish regained Naples and Sicily after the Battle of Bitonto in 1738.

Spanish and Austrian power was not always direct rule. States like Venice, Genoa, the Papal States, and the duchies of Este and Duchy of Savoy were independent. Much of the rest of Italy relied on Spain or Austria for protection. Also, areas under direct Spanish or Austrian control were often still seen as independent. They were linked to Spain and Austria only through their rulers.

Italy's economy and society began to decline as the 16th century went on. The Age of Discovery moved Europe's trade center from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. This made the Italian states less important. Venice kept fighting the Ottoman Empire for control of trading posts. It took part in the big naval Battle of Lepanto in 1571. In the next century, it fought the Turks in the Cretan War. Venice gained control of the Peloponnese in Greece but lost Crete. Crete was Venice's largest and richest overseas land. Venice had one last big military success helping to defeat the Ottoman Empire in the war of 1683–1699. By the 18th century, Venice's economy shrank. The city became quiet and easy for the French armies to take in 1796.

The Papal States also lost much of their power. The Protestant Reformation divided Europe into two groups. Catholic rulers wanted more control in their own lands. They often argued with the Pope about legal matters. The Popes often acted as peacemakers between France and Spain. Relations with France got worse during the reign of Louis XIV. But then they found common ground in stopping a religious movement called Jansenism. Even in Italy, the Papal States became less important politically. The Popes of the Counter-Reformation focused on religious issues. They worked to stop banditry and improve the court system. They also built many beautiful buildings in Rome. Gregory XIII introduced the calendar named after him. The Pope's fleet helped in the Battle of Lepanto. Besides losing political power, the Church faced more criticism during the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century.

As Spain declined in the 16th century, so did its Italian lands. These included Naples, Sicily, Sardinia, and Milan. Southern Italy became poor, stagnant, and cut off from Europe's main events. Naples was one of Europe's most crowded and dirty cities. It had many crimes and restless people. The rich families in Naples disliked Spanish rule. They welcomed the Austrians in 1707. But they were disappointed. Vienna did not give Naples any freedom. While the war raged, Austria put heavy taxes on Naples. They only started to manage the city well after peace returned. Graf von Daun, a viceroy from 1713 to 1719, tried some changes. But he argued with the church over legal issues. He mostly made peace with Rome. But international problems made Austrian emperors tax Naples more. They ignored everything except the city's old feudal lords. Cardinal Michael Friedrich von Althann became viceroy next (1722–1728). But he upset the rich families and middle class. He favored the church too much. Althann tried to create a state bank. This was meant to get land for the Austrian emperor. This plan angered both the rich and middle classes. After he was removed, Naples suffered years of famine and unrest. International problems stopped any attempts at reform. People were relieved when the Spanish-born Don Carlos became King of Naples in 1734. In 1759, he left to become King Charles III of Spain. His young son Ferdinand took over. The government was left to a regent, Bernardo Tanucci. Tanucci tried to make reforms in the spirit of the Enlightenment. He wanted to weaken the power of old Neapolitan groups. Ferdinand became an adult in 1767. But he was not interested in ruling. His wife, Maria Carolina, mostly controlled him. She disliked Tanucci's pro-Spanish views. She replaced him with Sir John Acton, an English person. When the French Revolution started, they joined Austria and Britain against France.

Sicily, on the other hand, had peaceful relations with Spain. The Spanish mostly let the island manage its own affairs. Sicily was an important outpost in the Mediterranean. It was also a key trading partner for Spain. So, friendly ties were important. After Sicily came under Austrian rule in 1720, problems started. Vienna placed German troops on the island permanently. This led to frequent and violent clashes with local people. Sicilian society was corrupt and behind the times. This made it hard to set up a working government. Like Naples, Sicily had to pay huge taxes to Vienna.

However, Emperor Charles VI tried to boost Sicily's economy. He made Messina and other places important ports. This was to attract foreign trade. He also tried to help the island's struggling grain and silk industries. But the emperor could not stop an economic downturn. Many of his projects failed. This led to a near-total economic collapse.

Charles had a difficult religious situation in Sicily. The king traditionally served as a church representative. He wanted to keep this role at all costs. He also promised to defend the Catholic faith. He and his ministers successfully discussed this with the Popes. They made peace with the Vatican. In the end, Austrian rule had little lasting impact on Sicily. Spanish troops took control of the island in 1734.

Sardinia was also left mostly alone. Many Spaniards settled on the island. Its economy was mainly based on sheep farming. It had little contact with the rest of Italy. Corsica passed from the Republic of Genoa to France in 1769. This happened after the Treaty of Versailles. Italian was the official language of Corsica until 1859.

The Age of Enlightenment in Italy

The Enlightenment played a special, though small, role in 18th-century Italy. This was from 1685 to 1789. While much of Italy was controlled by traditional Habsburgs or the Pope, Tuscany had chances for change. Leopold II of Tuscany ended the death penalty in Tuscany. He also reduced censorship. From Naples, Antonio Genovesi (1713–69) influenced many thinkers and students. His book "Diceosina" (1766) tried to link moral philosophy with problems of 18th-century business. It contained most of Genovesi's ideas on politics, philosophy, and economics. It was a guide for Naples' economic and social growth. Science also thrived. Alessandro Volta and Luigi Galvani made big discoveries in electricity. Pietro Verri was a leading economist in Lombardy. Historian Joseph Schumpeter called him a very important expert on economic prosperity. Franco Venturi is the most influential scholar on the Italian Enlightenment.

Italy During the Napoleonic Era

By the late 18th century, Italy's political situation was similar to the 16th century. The main difference was that Austria had replaced Spain as the main foreign power. This happened after the War of Spanish Succession. However, this was not true for Naples and Sicily. Also, the dukes of Savoy, a mountain region, had become kings of Sardinia. They had increased their Italian lands. These now included Sardinia and the north-western region of Piedmont.

The French Revolution caught a lot of attention in Italy from the start. This was because attempts at reform by rulers in the 18th century had largely failed. Secret societies called Masonic lodges grew in number. In these groups, smart people discussed big changes.

The rulers in Italy were completely against the ideas from France. They cracked down hard on anyone who disagreed. As early as 1792, French armies entered Italy. That same year, poor farmers in Piedmont warned their king. They said he might face the same fate as Louis XVI in France. The middle class in Rome rebelled against the Pope's political power. In Venice, the middle class and rich families spoke out against their city's government.

However, most of these protests did not achieve much outside Piedmont and Naples. In the south, a plot by pro-republican Freemasons was discovered. Their leaders were executed. Dozens of people who disagreed fled to France. One of them, Filippo Buonarroti, came back to Italy with the French armies. He briefly set up a revolutionary government in Oneglia. The special rights of the rich were removed. The Church was replaced by a new religion. But after Robespierre, whom Buonarroti admired, lost power in France, Buonarroti was called back. His experiment quickly ended.

This situation changed in 1796. The French Army of Italy, led by Napoleon, invaded Italy. Their goals were to make the First Coalition leave Sardinia. They also wanted to force Austria out of Italy. The first battles were on April 9 between the French and the Piedmontese. Within just two weeks, Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia had to sign a peace agreement. On May 15, the French general entered Milan. He was welcomed as a liberator. He then fought off Austrian attacks and kept moving forward. He reached the Veneto region in 1797. Here, the Veronese Easters happened. This was a rebellion against French rule. It kept Napoleon busy for about a week.

In October 1797, Napoleon signed the Treaty of Campo Formio. By this treaty, the Republic of Venice became part of Austria. This crushed the hopes of Italian nationalists for an independent Venice. This treaty also made Austria recognize the Cisalpine Republic. This republic included Lombardy, Emilia Romagna, and small parts of Tuscany and Veneto. Piedmont was also added to France. Even though these new states were controlled by France, they sparked a nationalist movement. The Cisalpine Republic became the Italian Republic in 1802. Napoleon was its president. Since these republics were created by an outside force, they had little public support. This was especially true because the French were against the church, which upset farmers. It would take a real movement from the people to bring change. Also, even Italian republicans became disappointed. They realized the French wanted them to be obedient to Paris. This included frequent meddling in local matters and huge taxes. However, returning to the old feudal system was also not wanted. So, the republican movement slowly changed its goals to nationalism and a united Italian state.

After the War of the First Coalition ended, French attacks in Italy continued. In 1798, they took Rome. They sent the Pope into exile. They set up a republic there. When Napoleon left for Egypt, King Ferdinand VI of Sicily retook Rome. He brought the Pope back. But as soon as his armies left, the French returned. They occupied Naples. Ferdinand's court fled to Sicily with British help. Another republic was set up, called the Parthenopean Republic. It governed in a more radical and democratic way. But Ferdinand cleverly organized a counter-revolt. It was led by his agent, Cardinal Fabrizio Ruffo. Ruffo landed in Italy and gathered a mob of farmers. They retook Naples. They then robbed and destroyed the homes of the hated rich families. There were also many killings of middle-class people who had supported the French. Afterward, Ferdinand returned to his capital in triumph. One hundred revolutionary leaders were quickly tried and executed.

In northern Italy, the French occupied Tuscany in the spring of 1799. But another farmer uprising drove them out. That fall, the Roman Republic also fell apart. The French were almost completely gone from Italy by then.

After taking power as consul in France, Napoleon invaded Italy again. Milan fell on June 2, 1800. Austrian defeats there and in Germany ended the War of the Second Coalition. Austria kept only control of Venetia. France controlled the rest of northern Italy. Only the weak Papal and Neapolitan states remained in the south. Over the next few years, Napoleon combined his Italian lands into one Republic of Italy. It was ruled by Francesco Melzi d'Eril. But in 1805, Napoleon decided to change the republic into a kingdom. His stepson, Eugene D'Beauharnais, ruled it. The Kingdom of Italy slowly grew. Austria gave up Venetia in 1806, and other lands were added. Still other Italian regions were directly added to France. In 1809, the French reoccupied Rome. They took Pope Pius VII prisoner.

Ferdinand VI's lands in southern Italy stayed independent for the first few years of the 19th century. But they were too weak to resist a strong attack. A French army quickly took Naples in early 1806. Ferdinand's court fled to Sicily. There, they had British protection. Napoleon made his brother Joachim king of Naples. But Joachim only ruled the mainland. Sicily and Sardinia stayed out of French control. During the years the Bourbon family was in exile in Sicily, the British gained political control. They forced Ferdinand to make some democratic reforms. But when the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, the king returned to Naples. He went back to ruling as an absolute monarch.

Joachim Bonaparte, meanwhile, followed his own policies, separate from France. He made several reforms that strengthened the middle class in Naples. However, he and the other rulers allied with Napoleon lost power in 1814–15.

In 1805, after the French victory over the Third Coalition and the Peace of Pressburg, Napoleon got back Veneto and Dalmatia. He added them to the Italian Republic and renamed it the Kingdom of Italy. Also that year, another state, the Ligurian Republic, was forced to join France. In 1806, he conquered the Kingdom of Naples. He gave it to his brother, and then to Joachim Murat from 1808. He also married his sisters Elisa and Paolina to princes in Massa-Carrara and Guastalla. In 1808, he also added Marche and Tuscany to the Kingdom of Italy.

In 1809, Bonaparte occupied Rome. He argued with the Pope, who had excommunicated him. To keep the state running, he exiled the Pope first to Savona and then to France. He also took the Papal States' art collections to the Louvre. Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1811 marked the end of Italian support for him. Many Italians died in this failed campaign.

After Russia, other European states joined forces. They defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Leipzig. After this, his Italian allies, with Murat first among them, left him to join Austria. Napoleon was defeated in Paris on April 6, 1814. He had to give up his throne and was sent to exile on Elba. The Congress of Vienna (1814) brought things back to how they were around 1795. Italy was divided among Austria (in the north-east and Lombardy), the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (in the south and Sicily), and Tuscany. The Papal States and other smaller states were in the center. However, old republics like Venice and Genoa were not brought back. Venice went to Austria, and Genoa went to the Kingdom of Sardinia.

When Napoleon escaped and returned to France (the Hundred Days), he regained Murat's support. But Murat could not convince Italians to fight for Napoleon with his Proclamation of Rimini. Murat was killed. The Italian kingdoms then fell. Italy's Restoration period began. Many rulers from before Napoleon returned to their thrones. Piedmont, Genoa, and Nice were united. Sardinia also joined, creating the State of Savoy. Lombardy, Veneto, Istria, and Dalmatia were returned to Austria. The duchies of Parma and Modena were reformed. The Papal States and the Kingdom of Naples returned to the Bourbon family. The political and social events in Italy's restoration period (1815–1835) led to uprisings. These greatly shaped what would become the Italian Wars of Independence. All this led to a new Kingdom of Italy and Italian unification.

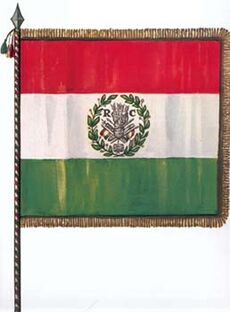

During the Napoleonic era, in 1797, the Cispadane Republic officially adopted the first Italian tricolour as a national flag. This was a state created by Napoleon. It was based on the ideas of the French Revolution (1789–1799), which supported national self-determination. This event is celebrated on Tricolour Day. The Italian national colours first appeared on a tricolour cockade in 1789. This was seven years before the first green, white, and red Italian military flag. That flag was adopted by the Lombard Legion in 1796.

What Happened Next: Unifying Italy

After Napoleon's fall in 1814, old absolute monarchies returned. The Italian tricolour flag went underground. It became a secret symbol for patriotic feelings spreading in Italy. It united all efforts of the Italian people for freedom and independence.

Between 1820 and 1861, a series of events led to Italy's independence and unification. This period is known as the Risorgimento. The Italian tricolour waved for the first time in the Risorgimento on March 11, 1821. This happened in the Cittadella of Alessandria. It was during the revolutions of the 1820s. This was after the flag had been hidden due to the return of the old monarchies.

See also

- Sister republic

- 130 departments of the First French Empire (includes former Italian lands France took)

- List of historic states of Italy

- King of Italy (includes a list of modern kings of Italy)

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |