History of paleontology facts for kids

The history of paleontology is the story of how people have tried to understand the past life on Earth. They do this by studying fossils. Fossils are the preserved remains or traces of ancient living things. Paleontology is a part of biology, which is the study of life. But it's also closely linked to geology, which is the study of Earth's history.

Long ago, thinkers like Xenophanes (570–480 BC) and Herodotus (484–425 BC) wrote about marine fossils. They realized these fossils meant that land was once covered by water. In ancient China, people thought fossils were dragon bones.

During the Middle Ages, the Persian scientist Ibn Sina (around 1027) suggested that fossils formed from "petrifying fluids." Later, the Chinese scientist Shen Kuo (1031–1095) used fossilized bamboo to suggest that Earth's climate had changed over time.

In early modern Europe, people started studying fossils more carefully. By the end of the 18th century, Georges Cuvier proved that extinction was real. This helped paleontology become a true science. As more fossils were found, scientists learned more about Earth's long history.

The word "paleontology" was first used in 1822. In the early 1800s, geology and paleontology became more organized. Scientists formed societies and museums. This led to a huge increase in knowledge about life's history. It also helped create the geologic time scale, which uses fossils to mark different periods.

After Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, paleontology focused on understanding evolution. This included human evolution. The late 1800s saw many fossil discoveries, especially in North America. This continued into the 20th century, with important finds in places like China. Many transitional fossils have been found, showing how different groups of animals are related. Recent discoveries have also taught us about mass extinctions and the amazing burst of life called the Cambrian explosion.

Contents

Early Discoveries (Before the 17th Century)

As far back as the 6th century BC, the Greek thinker Xenophanes of Colophon (570–480 BC) knew that some fossil shells were from shellfish. He used this to argue that dry land was once under the sea. Much later, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) also figured out that fossil seashells were once living creatures. These early examples were easy to understand because the fossils looked like living shellfish.

In 1027, the Persian scientist Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in Europe) wrote about how fossils turned to stone. He thought it was due to "petrifying fluids." This idea was popular for centuries.

Shen Kuo (1031–1095) from China used marine fossils found in mountains to suggest that land and sea levels change over time. In 1088 AD, he found fossilized bamboo underground in a dry area. He used this to argue that the climate had changed, as bamboo needs a wet climate to grow.

By the 16th century, European scientists started collecting fossils. They stored them in special cabinets. These collections and the letters scientists wrote to each other helped natural philosophy grow.

However, most people in the 16th century didn't think fossils were once living things. The word "fossil" came from a Latin word meaning "dug up." It was used for any interesting stone. Many believed that stones could grow in the earth to look like living things.

Leonardo da Vinci's Fossil Ideas

Leonardo da Vinci was very advanced in his thinking about fossils. He studied both body fossils (like shells) and trace fossils (like burrows or tracks). In his notebooks, he wondered why petrified seashells were found on mountains. He correctly understood that these were real shells and that the rocks they were in were once mud on the seabed.

Leonardo's ideas were very new for his time. He used trace fossils to prove his points. He described fossilized holes made by ancient animals in shells, just like woodworms make holes in wood. This showed him that the "petrified shells" were indeed once living.

He also studied fossil burrows. He used them to show that rock layers were formed from sea mud. Leonardo's ideas about trace fossils were so modern that they weren't fully understood by other scientists until the early 1900s! Because of his insights, Leonardo da Vinci is seen as a founder of paleontology.

17th Century Discoveries

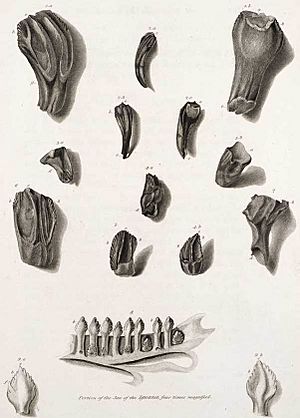

In 1665, Robert Hooke published his book Micrographia. He showed detailed drawings of things seen through a microscope. One part compared petrified wood to regular wood. He concluded that petrified wood was ordinary wood soaked in "stony and earthy particles." He also thought fossil seashells formed in a similar way. Hooke believed fossils were proof of past life on Earth. He even thought some fossils might be from species that had gone extinct due to past disasters.

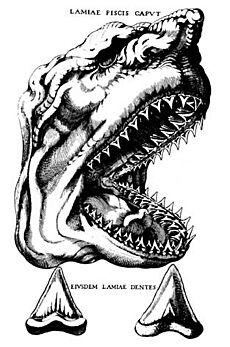

In 1667, Nicholas Steno studied a shark's head. He compared its teeth to common fossils called "tongue stones." He realized these fossils were actually shark teeth! Steno then studied rock layers. In 1669, he published his ideas. He explained that some rocks formed from layers of sediment, and fossils were remains of living things buried in that sediment. Steno, like most people then, believed Earth was only a few thousand years old. So, he thought the Biblical flood might explain marine fossils found far from the sea.

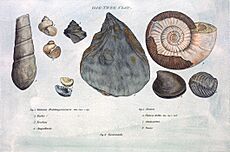

Some scientists, like Martin Lister, still doubted that all fossils were organic. They especially wondered about fossils like Ammonites, which didn't look like any living species. This raised the difficult idea of extinction.

18th Century Discoveries

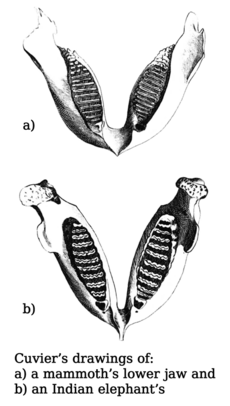

In 1796, Georges Cuvier compared the bones of living elephants to mammoths and mastodons. He proved that mammoths and mastodons were different species from modern elephants and were extinct. This was a huge step! Cuvier also identified Megatherium as a giant sloth from a fossil skeleton. Cuvier's work helped everyone accept that species could go extinct. He also suggested that Earth had experienced several catastrophes that wiped out life forms.

Around the same time, William Smith, a surveyor, used fossils to map rock layers. He found that each layer of rock had specific types of fossils. These fossils appeared in a predictable order, even in different places. This idea is called the principle of faunal succession. It was very useful for understanding geology.

Early to Mid-19th Century

The Birth of Paleontology

In 1812, Georges Cuvier published a major work on fossil bones. In 1822, a French scientist named Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville used the word palæontologie (paleontology) for the first time in print. He wanted a word that covered the study of both fossil animals and plants. This new word quickly became popular.

In 1828, Adolphe Brongniart, a botanist, studied fossil plants. He divided plant history into four main periods. Each period had different types of plants, showing that life on Earth had changed a lot over time. His work helped create paleobotany, the study of fossil plants. He also concluded that Northern Europe had a tropical climate during the Carboniferous period, based on plant fossils.

The Age of Mammals

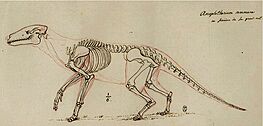

In 1804, Cuvier found two new fossil mammal types, Palaeotherium and Anoplotherium, in Paris. These were older than previously found mammals. He figured out they were mammals but different from any living ones. He even reconstructed their skeletons and guessed how they lived. His work helped start the study of ancient mammals.

The Age of Reptiles

In 1808, Cuvier identified a fossil from Maastricht as a giant marine reptile, later called Mosasaurus. He also identified a flying reptile, Pterodactylus. He thought these large reptiles lived before the "age of mammals."

This idea was supported by amazing discoveries in Great Britain. Mary Anning, a professional fossil collector from a young age, found many marine reptile and fish fossils in Lyme Regis. She found the first complete ichthyosaur skeleton in 1811 and the first two plesiosaur skeletons in the early 1820s. Mary Anning was only 12 when she helped find the Ichthyosaurus! She also noticed that strange stony objects, called "bezoar stones," were found inside ichthyosaur skeletons. She realized they were fossilized poop, which scientists later called coprolites. This helped them understand ancient food chains. Mary Anning made huge contributions to science, but often didn't get the credit she deserved.

In 1824, William Buckland found a jawbone from a large meat-eating land reptile, which he named Megalosaurus. That same year, Gideon Mantell found large teeth that looked like those of an iguana. He named the creature Iguanodon. In 1831, Mantell published "The Age of Reptiles," showing that Earth had a long period dominated by giant reptiles. In 1841, Richard Owen created the term Dinosauria for these amazing creatures.

Catastrophism and Uniformitarianism

Cuvier believed in Catastrophism, meaning that Earth's history was shaped by sudden, violent events that caused mass extinctions. In Britain, some linked these catastrophes to the Biblical flood.

However, Charles Lyell argued for Uniformitarianism in his book Principles of Geology. He believed that Earth's features were formed by slow, ongoing processes like volcanoes and erosion, acting over very long periods. He thought that changes in the fossil record were due to gaps in the record, not sudden catastrophes. Lyell convinced many geologists that Earth's changes were slow and continuous, though his ideas about the fossil record were less accepted at first.

Early Ideas about Evolution

In the early 1800s, Jean Baptiste Lamarck used fossils to support his idea that species could change over time. Other books, like Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844), also suggested that life had evolved from simple to complex forms. These early ideas were debated, but they helped prepare the way for Darwin's theory of evolution.

The Geological Time Scale

By the 1840s, much of the geologic time scale was developed. John Phillips divided Earth's history into three main eras: the Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic. These divisions were based on big changes in the fossil record. Scientists realized there was an "age of reptiles" before the "age of mammals." They also knew that early life was only in the sea, and that invertebrates were the largest animals before the Devonian period.

Growth of Paleontology

The rapid progress in paleontology in the 1830s and 1840s was helped by a growing network of scientists. Many paleontologists became paid professionals working for universities, museums, and government surveys. Public support for earth sciences grew because of their cultural impact and their help in finding resources like coal.

Museums with large natural history collections also played a key role. The Museum of Natural History in Paris was very important. It was home to Cuvier and other leading scientists, and it helped train many future paleontologists.

Late 19th Century

Evolution and Fossils

Charles Darwin's book On the Origin of Species (1859) changed everything for life sciences, especially paleontology. Darwin had been impressed by fossils he found in South America, like giant armadillos, which seemed related to living species. After his book, scientists actively looked for transitional fossils to support evolution.

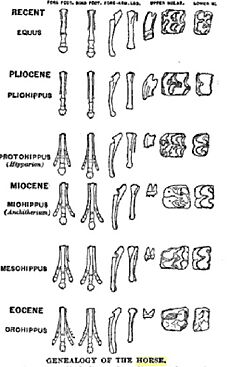

Two big successes were finding links between reptiles and birds, and showing how horses evolved. In 1861, the first Archaeopteryx fossil was found. It had both teeth and feathers, showing a mix of reptile and bird features. Later, Othniel Marsh found primitive toothed birds and several early horse fossils in the Western United States. These fossils showed how horses evolved from small, five-toed creatures to the large, single-toed horses we know today.

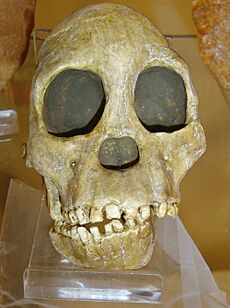

There was also great interest in human evolution. Neanderthal fossils were found in 1856. In 1891, Eugene Dubois found Java Man, which was clearly a link between humans and apes.

Paleontology in North America

The second half of the 19th century saw a huge growth in paleontology in North America. In 1858, Joseph Leidy described a Hadrosaurus skeleton, the first good dinosaur fossil from North America. The building of railroads and settlements in the Western United States after the American Civil War led to many fossil discoveries.

This led to a better understanding of North America's ancient past, including the Western Interior Sea that once covered parts of the Midwest. Many new dinosaur types were found, like Allosaurus, Stegosaurus, and Triceratops. Much of this was part of a fierce rivalry between two paleontologists, Othniel Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope, known as the Bone Wars.

20th Century Discoveries

New Geological Tools

Two big developments in geology in the 20th century helped paleontology a lot. First, radiometric dating allowed scientists to figure out the exact age of rocks and fossils. Second, the theory of plate tectonics helped explain why certain ancient life forms were found in different parts of the world.

Global Paleontology

In the 20th century, fossil hunting became a global activity, not just in Europe and North America. Between 1969 and 1994, the number of known dinosaur types almost doubled! This was thanks to new discoveries in places like South America and Africa. Near the end of the century, China opened up to fossil exploration, leading to amazing finds about dinosaurs and the origins of birds and mammals.

Mass Extinctions Revisited

The 20th century saw a renewed interest in mass extinctions. In 1980, Luis and Walter Alvarez suggested that an impact event (like an asteroid hitting Earth) caused the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, which killed off the dinosaurs. Around the same time, scientists like Jack Sepkoski found patterns of repeated mass extinctions in the fossil record.

Evolutionary Paths and Theory

New fossil finds in the 20th century continued to show how evolution happened. For example, fossils in Greenland showed how tetrapods (four-legged animals) evolved from fish. Fossils in China showed the link between dinosaurs and birds. Discoveries in Pakistan shed light on whale evolution. And famous finds in Africa, like the Taung child in 1924, helped us understand human evolution.

Paleontology also helped shape evolutionary theory. In 1944, George Gaylord Simpson showed that the fossil record fit with Darwin's ideas of evolution through natural selection. In 1972, Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould used fossil evidence to propose punctuated equilibrium. This idea suggests that evolution has long periods of little change, followed by shorter periods of rapid change.

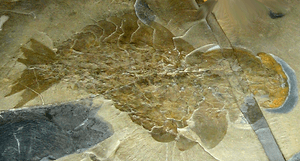

The Cambrian Explosion

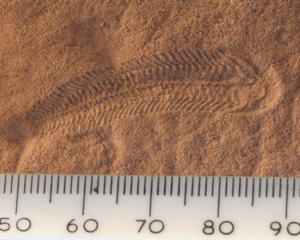

The Cambrian explosion is a period when many different animal groups suddenly appeared in the fossil record. The famous Burgess Shale fossil site was found in 1909. New studies in the 1980s sparked a lot of interest and new discoveries, including the Sirius Passet site in Greenland.

Pre-Cambrian Fossils

Before 1950, there wasn't much accepted fossil evidence of life before the Cambrian period. Darwin himself wondered about this gap. However, in the 1950s, scientists found more stromatolites (layered rocks made by bacteria) and tiny fossils of bacteria. A big breakthrough came when Martin Glaessner showed that soft-bodied animal fossils found in Australia were from the Ediacaran biota, making them the oldest known animals. By the end of the 20th century, paleobiology had shown that life on Earth goes back at least 3.5 billion years!

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la paleontología para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la paleontología para niños

- History of biology

- History of evolutionary thought

- History of geology

- History of science

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of years in paleontology

- Taxonomy of commonly fossilised invertebrates

- Timeline of paleontology

- Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology

- History of paleontology in the United States