History of geology facts for kids

The history of geology is all about how we came to understand our amazing planet, Earth! Geology is the science that studies how Earth was formed, its long history, and what it's made of.

Contents

Ancient Times

Around 540 BC, a thinker named Xenophanes noticed something strange: he found fossil fish and shells high up on mountains! This was a big clue that these areas were once under water. Later, Herodotus (around 490 BC) also saw similar fossils.

People in Ancient Greece started thinking about how Earth began. In the 4th century BC, the famous philosopher Aristotle watched how land slowly changed. He realized that Earth changes very gradually, so slowly that one person wouldn't see big changes in their lifetime. He was one of the first to use evidence to think about how Earth physically changes.

However, it was Theophrastus, who took over from Aristotle, who made the biggest steps in ancient geology. In his book On Stones, he described many minerals and ores (rocks with valuable metals). He talked about different types of marble and building materials like limestone. He even tried to sort minerals by their features, like how hard they were.

Much later, in Ancient Rome, Pliny the Elder wrote a lot about minerals and metals used in daily life. He was one of the first to correctly figure out that amber is actually fossilized tree resin. He noticed insects trapped inside some pieces, which was a great clue! He also helped start the study of crystallography by seeing the special eight-sided shape of diamonds.

Middle Ages

Abu al-Rayhan al-Biruni (AD 973–1048) was an early Muslim geologist. He wrote about the geology of India and thought that the Indian subcontinent was once covered by a sea.

Ibn Sina (AD 981–1037), a smart Persian scholar, made important contributions to geology. In his huge book, "Kitab al-Shifa", he wrote about how mountains form, where water comes from, why earthquakes happen, how minerals are made, and the different types of Earth's terrain.

In medieval China, a brilliant person named Shen Kuo (1031–1095) was one of the first to think about how landforms change (this is called geomorphology). He saw sedimentary rocks lifting up, soil erosion, and silt building up. He also found marine fossils in the Taihang Mountains, which were hundreds of miles from the Pacific Ocean. This made him guess that the land was formed by mountains eroding and silt being deposited. He also noticed ancient petrified bamboo in a dry area, which led him to think about gradual climate change.

17th Century

Geology really started to grow in the 17th century. It began to be seen as its own science. At this time, many people believed that a great Deluge, like the one in the Bible, had shaped Earth's geology. People wanted to find scientific proof for this Great Flood. This desire led to more observations of Earth's rocks and the discovery of fossils.

Even though many theories were made to support the Flood idea, it still led to a much greater interest in what Earth was made of. A popular theory about Earth's origin was A New Theory of the Earth, published in 1696 by William Whiston. Whiston used religious ideas to "prove" that the Great Flood happened and formed Earth's rock layers.

During this century, both religious and scientific ideas about Earth's origin pushed people to study Earth more closely. They started to identify Earth's strata (horizontal layers of rock) in a more organized way. A very important person in this field was Nicolas Steno. He questioned old ideas, like that fossils grew in the ground. His studies on rock formation and fossils led many to see him as a founder of modern stratigraphy (the study of rock layers) and geology.

18th Century

As people became more interested in Earth, they paid more attention to minerals and other parts of Earth's crust. Also, mining became very important in Europe, so knowing where to find ores (rocks with valuable minerals) was vital. Scholars began to study Earth's makeup in a careful way, describing not just the land but also the valuable metals it contained.

For example, in 1774, Abraham Gottlob Werner wrote a book called On the External Features of Fossils. He became famous because he created a detailed system to identify minerals based on how they looked. The better people could find valuable land for mining, the more money could be made. This desire for wealth made geology a popular subject to study, leading to more detailed observations and information about Earth.

Also in the 18th century, the age of Earth became a hot topic. People started to question the accepted religious idea of a young Earth. In 1749, the French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon published his Histoire Naturelle. He disagreed with the idea that Earth was only a few thousand years old, as suggested by the Bible. From his experiments, he thought Earth was at least 75,000 years old. Another thinker, Immanuel Kant, also wrote about Earth's history without mentioning God or the Bible. By the mid-18th century, it became okay to question Earth's age scientifically, without religious ideas getting in the way.

With scientific methods applied to Earth's history, geology could become its own science. The word "geology" was first used technically by Jean-André Deluc and Horace-Bénédict de Saussure. It became widely known after being used in the famous Encyclopédie (a big book of knowledge) starting in 1751. Once the term was set, geology slowly became recognized as a science that could be taught in schools. In 1741, the National Museum of Natural History in France created the first teaching job specifically for geology. This helped spread knowledge about geology as a science.

By the 1770s, chemistry played a big role in geology. Two main theories emerged about how Earth's rock layers formed. One idea, called Neptunism, suggested that a great flood (like the biblical one) created all geological layers. This theory was popular with chemists and promoted by people like Abraham Werner. He believed that all Earth's layers, even hard rocks like basalt and granite, formed from chemicals settling out of a global ocean.

However, another idea slowly gained ground from the 1780s. Some naturalists, like Buffon, thought that heat (or fire) formed the layers. This idea was developed by the Scottish naturalist James Hutton. He disagreed with Neptunism and proposed Plutonism. This theory said that Earth formed from molten rock slowly cooling and solidifying, with the same processes happening over long periods. This led him to believe that Earth was incredibly old, much older than what the Bible suggested. Plutonists thought that volcanic activity was the main way rocks formed, not water from a Great Flood.

19th Century

In the early 1800s, the mining industry and the Industrial Revolution helped geology grow fast. People started to create the "stratigraphic column," which is a way to organize rock layers by their age. In England, a surveyor named William Smith found that fossils were great for telling different rock layers apart. He traveled the country working on canals and made the first geological map of Britain.

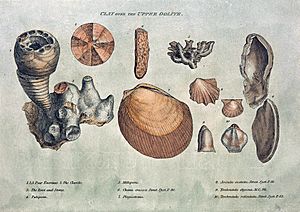

Around the same time, in France, Georges Cuvier and Alexandre Brogniart realized that the age of fossils could be figured out by looking at which rock layer they were in and how deep that layer was. They found that different rock layers could be identified by the fossils they contained. After they published their book in 1811, stratigraphy became very popular. Geologists wanted to apply this idea to all rocks on Earth. Over this century, geologists like Adam Sedgwick and Roderick Murchison continued to refine and complete the stratigraphic column. This column was important because it gave a way to figure out the relative age of rocks by placing them in their correct sequence. This helped geologists worldwide compare rocks from different countries.

In early 19th-century Britain, the idea of catastrophism was used to try and match geology with the biblical Great Flood. Geologists like William Buckland thought that certain deposits were from Noah's flood. But later, they changed their minds, thinking they were from local floods instead.

Charles Lyell challenged catastrophism with his book Principles of Geology, published in 1830. He showed lots of evidence from different countries to prove Hutton's ideas of gradual change were right. He argued that most geological changes happened very slowly over human history. Lyell provided evidence for Uniformitarianism, which is the idea that the same slow processes we see today have been happening throughout Earth's history and explain all its features. Lyell's books were very popular, and uniformitarianism became a strong idea in geology.

In 1831, Captain Robert FitzRoy needed a naturalist for his ship, HMS Beagle, to explore coastlines. He chose Charles Darwin, who had just finished his degree and studied geology. Fitzroy gave Darwin Lyell's Principles of Geology. Darwin became a big supporter of Lyell's ideas. He used uniformitarian principles to understand the geological processes he saw. He even came up with his own ideas, like how coral atolls (ring-shaped coral reefs) form around sinking volcanic islands. This idea was proven correct when the Beagle explored the Cocos (Keeling) Islands. Darwin's discovery of huge fossils also helped his reputation as a geologist. His thoughts on why these animals went extinct later led to his famous theory of evolution by natural selection, published in On the Origin of Species in 1859.

Governments started to support geological research because it was useful for the economy. In the 19th century, countries like Canada, Australia, Britain, and the United States began geological surveys to create maps of their land. These maps showed where useful rocks and minerals were, which helped the mining industry. With government and industry funding, more people studied geology, and new technologies improved the field.

In the 19th century, geologists estimated Earth's age to be millions of years. But in 1862, the physicist William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, calculated Earth's age to be between 20 million and 400 million years. He thought Earth started as a completely molten ball and figured out how long it would take to cool. Many geologists felt his estimates were too short to explain the thick layers of rock and the evolution of life. However, the discovery of radioactivity in the early 1900s showed there was another heat source inside Earth. This allowed for a much older age calculation and a way to date geological events.

20th Century

By the early 1900s, scientists discovered radioactive elements and developed radiometric dating. This method uses the decay of radioactive elements to measure geological time. In 1911, Arthur Holmes, a pioneer in this field, dated a rock sample from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to be 1.6 billion years old using lead isotopes. In 1913, Holmes published his famous book The Age of the Earth. He strongly argued for using radiometric dating instead of older methods based on sedimentation or Earth's cooling. Many people still believed Lord Kelvin's calculations of less than 100 million years. Holmes estimated the oldest rocks to be 1.6 billion years old. His work over the next decades earned him the nickname "Father of Modern Geochronology" (the science of dating Earth's history). In 1921, scientists agreed that Earth was a few billion years old and that radiometric dating was reliable. Holmes later updated his estimate to 4.5 billion years. Theories that didn't match this scientific evidence could no longer be accepted. The accepted age of Earth has been refined since then but hasn't changed much.

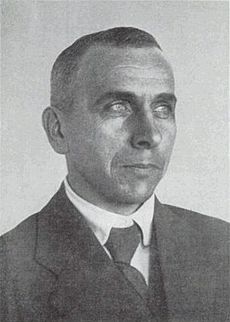

In 1912, Alfred Wegener proposed the theory of continental drift. This idea suggested that the shapes of continents, like South America and Africa, and matching geology on their coastlines, meant they were once joined together. He thought they formed a single huge landmass called Pangaea. Then, they slowly separated and drifted apart like rafts over the ocean floor to their current positions. This theory also offered a possible explanation for how mountains formed. The later theory of plate tectonics built on Wegener's ideas.

Sadly, Wegener couldn't explain how the continents moved, so his ideas weren't widely accepted during his lifetime. Arthur Holmes, however, believed Wegener's theory and suggested a mechanism: mantle convection, which is the slow movement of molten rock deep within Earth. But it wasn't until after World War II that new evidence started to support continental drift.

Over the next 20 years, continental drift went from being believed by a few to becoming the main idea in modern geology. Starting in 1947, research provided new evidence about the ocean floor. In 1960, Bruce C. Heezen published the idea of mid-ocean ridges (underwater mountain ranges). Soon after, Robert S. Dietz and Harry H. Hess proposed seafloor spreading. This idea said that new oceanic crust forms as the seafloor spreads apart along mid-ocean ridges. This confirmed the idea of mantle convection, removing the biggest problem with Wegener's theory.

Geophysical evidence showed that continents moved sideways and that oceanic crust was younger than continental crust. This evidence also led to the idea of paleomagnetism, which is the record of Earth's magnetic field stored in magnetic minerals in rocks. British geophysicist S. K. Runcorn suggested paleomagnetism from his finding that continents had moved relative to Earth's magnetic poles. Tuzo Wilson, who supported seafloor spreading and continental drift from the start, added the idea of transform faults (a type of fault) to the model. This completed the picture of how Earth's plates could move. A meeting in London in 1965 is seen as the official start of the scientific community accepting plate tectonics. By the late 1960s, the evidence was so strong that continental drift became the widely accepted theory.

Modern Geology

By applying smart ways of studying rock layers to the distribution of craters on the Moon, Gene Shoemaker quickly shifted the study of the Moon from astronomers to Lunar geologists.

In recent years, geology continues to study Earth's features and its inside structure. What changed in the late 20th century is how geology is studied. It's now looked at in a more connected way, considering Earth as part of a bigger system that includes the atmosphere, living things (biosphere), and water (hydrosphere). Satellites in space that take wide pictures of Earth help with this view. In 1972, The Landsat Program, a series of satellite missions by NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey, began providing satellite images that can be studied geologically. These images help map large geological areas, identify rock types, and track the movements of plate tectonics. This data can be used to create detailed geological maps, find natural energy sources, and even predict natural disasters caused by plate shifts.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la geología para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la geología para niños

- History of geomagnetism

- History of paleontology

- Outline of Earth science

- Humboldtian science

- Timeline of geology

- Timeline of the development of tectonophysics (before 1954)

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |