History of slavery in West Virginia facts for kids

The western part of Virginia that later became West Virginia was settled from two main directions. People came from the north (like Pennsylvania, Maryland, and New Jersey) and from the east (from eastern Virginia and North Carolina). The first enslaved people arrived in the Shenandoah Valley counties, where important Virginia families built large homes and plantations. Records show that around 1748, there were about 150 enslaved people in Hampshire County on the land of Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron. By the early 1800s, slavery had spread all the way to the Ohio River in the northern part of the state.

Contents

- How Slavery Began in West Virginia

- What Enslaved People Did

- Slave Population in West Virginia

- Efforts to End Slavery and Support for It

- The American Colonization Society

- The Underground Railroad in West Virginia

- Slavery During the Civil War

- The Willey Amendment

- After the War: Reconstruction

- Civil Rights Efforts

- Images for kids

How Slavery Began in West Virginia

Early settlers who owned property often tried to create communities similar to those in eastern Virginia. They built grand homes on large estates. The eastern counties, especially Jefferson and Berkeley, looked a lot like eastern Virginia. Many famous families, like the Washingtons and Fairfaxes, owned land here. For example, in 1817, Colonel John Fairfax started building his big house, Fairfax Manor, with the help of his sons and 30 enslaved people. Their old log homes became the living quarters for the enslaved workers.

News about Ebenezer Zane's settlement near what is now Wheeling attracted new settlers. They were looking for cheap, fertile land. Some bought enslaved people in Maryland and northern Virginia on their way to the Kanawha and Ohio River valleys. After 1790, large areas of land were cleared for farming. Other settlers came from eastern Virginia and North Carolina. In the early 1800s, people traveling to the Missouri territory often stopped in the Kanawha Valley and stayed. They were drawn by the low cost of land and the money they could make by renting out their enslaved people to local salt producers.

In 1800, Harman Blennerhassett built a large, fancy home on Blennerhassett Island in the Ohio River. Similar large homes and enslaved workers soon appeared along the Ohio River. In 1814, Zadok Cramer wrote about his travels on the Ohio River, noting the clear difference between the two sides. On the Virginia side, there were large houses with "negro quarters" (slave housing). On the Ohio side, where slavery was not allowed, there were neat, comfortable small homes.

Wheeling was the biggest city in western Virginia and the fourth largest in all of Virginia. It was located between Ohio and Pennsylvania. The number of enslaved people in the northern panhandle was relatively small. By 1850, the four counties there had only 247 enslaved people. One of the northernmost plantations was Shepherd Hall, built in 1798. It had slave quarters, a mill, and a tannery.

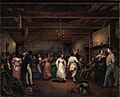

Wheeling became a major center for hiring out or selling enslaved people to the local salt industry and to markets further south. Slave auctions were held weekly in Wheeling and also in Charleston. When enslaved people were part of an estate (property left by someone who died), auctions were usually held at the county courthouse. In 1835, a large auction in Charlestown saw one enslaved man sell for $1200 and a woman with four children for $1950. Even though slave owners were a minority in West Virginia, they owned more land and wealth. They often held public offices, which allowed them to shape laws to benefit themselves.

What Enslaved People Did

By 1860, about 48% of enslaved labor in West Virginia was used in farming, 16% in trade, 21% in industry, and 15% in other jobs.

Farming Work

Farms in West Virginia produced about twice as much grain and livestock as was needed for the people living there. About one in ten farm workers was enslaved. Enslaved women worked in the fields alongside men. They also acted as drovers (herding animals), supervisors, and did general maintenance like cutting fence rails. Instead of having overseers, enslaved people were often given specific tasks to complete daily or weekly. Most enslaved people in agriculture worked on farms with fewer than 10 slaves, where owners often worked in the fields too. In wealthier homes, enslaved people worked as domestic servants.

Mining and Industry

Salt was one of West Virginia's first major exports. By 1828, 65 wells along the Kanawha River produced a huge amount of salt each year. By 1835, the salt industry used nearly 3,000 workers, mostly enslaved people. Much of Charleston's growth was due to this industry. By 1852, a fleet of 400 flatboats moved three million bushels of salt to markets in the south and midwest. The salt industry also led to more logging, coal mining, and gas extraction, all using more enslaved labor.

However, by 1860, salt production was slowing down. Enslaved people could be hired for half the cost of free workers and needed less supervision. Living conditions for enslaved people were very unhealthy, and outbreaks of diseases like cholera were common. In 1844, one hundred enslaved people died from cholera in just three months.

Coal was used to power the salt furnaces. By 1860, 25 companies were mining coal in West Virginia. These companies advertised for hired enslaved people, paying $120 to $200 a year for their labor. Women and children also worked in the mines. About 2,000 enslaved people were employed in coal mining.

By 1860, West Virginia had 14 iron plantations. One of the largest was Ice's Ferry Iron Works, which at its peak employed 1,700 enslaved and free workers. Enslaved labor made up about 75% of the workforce at these facilities.

Resorts and Recreation

The mineral springs in southern West Virginia were popular vacation spots for wealthy southern families. Presidents, Supreme Court justices, and politicians visited these resorts. Newspapers encouraged southerners to vacation in their own highlands instead of traveling north. Enslaved workers were recruited from Richmond to work at these resorts.

Sweet Springs was one of the oldest resorts, with its first hotel built in 1792. It had separate buildings for enslaved people and stables. The hotel was not allowed to sell alcohol to any free black person or enslaved person. Other popular resorts included Salt Sulphur Springs and Berkeley Springs.

Transportation and Trade

Enslaved people were used on rivers and land to transport West Virginia products like livestock, salt, grain, tobacco, lumber, and coal. Fleets of flatboats, manned by both enslaved and free workers, regularly left Charleston for markets in Cincinnati and New Orleans. The B&O Railroad hired and bought enslaved people to work on construction crews and in passenger service. Enslaved people were sometimes used in retail stores. In some towns, like Martinsburg, black people made up nearly one-third of the total residents.

Slave Population in West Virginia

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1820 | 15,178 |

| 1830 | 17,673 |

| 1840 | 18,488 |

| 1850 | 20,428 |

| 1860 | 18,371 |

Western Virginia's enslaved population reached its highest point in 1850 with 20,428 enslaved people, which was nearly 7% of the total population. By 1860, the number had dropped to 18,371. This decrease was mainly because there was a high demand for enslaved people in the lower South. The opening of new lands in Georgia and Alabama led to more cotton and tobacco farming, and the enslaved population there almost tripled from 1840 to 1860.

Groups of enslaved people, often tied together by rope, were frequently seen being moved overland to markets in the lower South. These groups were called "coffles." Enslaved people were often not told where they were going, to prevent them from running away or resisting. As the value of enslaved people increased in the 1840s and 1850s, some were even kidnapped and resold.

The 1860 U.S. Census counted 3,605 slave owners in West Virginia. Most of these (71%) owned 5 or fewer enslaved people. The largest numbers of enslaved people were in Jefferson (3,960), Kanawha (2,184), and Berkeley (1,650) counties. There were also 2,773 free black people living in West Virginia.

Efforts to End Slavery and Support for It

Unlike some other states, there wasn't a strong organized movement against slavery in West Virginia. Resistance to slavery usually came from religious groups or from people who believed it was bad for the economy. Some immigrant communities, like the Germans, were strongly against slavery. Some people in West Virginia also opposed slavery for political reasons. They felt that slaveholders from eastern Virginia had too much power in the government and received unfair tax benefits.

After Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831, the Virginia General Assembly (the state's lawmaking body) discussed solutions to the problems of slavery. Some suggested freeing all enslaved people immediately, others proposed freeing them gradually and sending them away, while some wanted things to stay the same. However, the General Assembly ended its session without taking any action.

In 1844, the Methodist Church split over whether its ministers could own enslaved people. A line was drawn, and north of it, including most of West Virginia, ministers were forbidden from owning slaves. However, many Methodist churches in West Virginia refused to follow this rule.

Henry Ruffner, a professor and president of Washington College, owned land and enslaved people himself. In 1847, he published a pamphlet called "An Address to the People of West Virginia." He argued for ending slavery in the western part of the state for economic and social reasons, believing that slavery held back development and growth.

In the 1840s, the Liberty Party, which was against slavery, tried to gain supporters in western Virginia. However, speaking out against slavery often led to violent reactions from those who supported it. Mobs attacked abolitionists in western Virginia many times. For example, in 1839, a mob from Guyandotte crossed the Ohio River and kidnapped a man to harm him.

The 1850–51 Constitutional Convention in Richmond tried to address some of West Virginians' complaints. It gave all white men over 21 the right to vote and gave western Virginia more representation in the House of Delegates. However, representation in the Senate was still unfair, with the east getting more senators. Slaveholders also gave themselves tax benefits: enslaved people under 12 were not taxed, and older ones were only taxed at a low value.

In 1856, Eli Thayer, an abolitionist from Massachusetts, tried to start a colony in Wayne County called Ceredo, where slavery would not exist. He faced strong opposition from U.S. Congressman Albert G. Jenkins, who owned a plantation with many enslaved people nearby. At first, the new settlement was welcomed, but after John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, local residents became hostile.

Sometimes, slave owners freed some or all of their enslaved people as part of their will after they died. For example, Sampson Sanders of Cabell County freed his enslaved people when he died in 1849. Because a Virginia law required newly freed people to leave the state within one year, most wills provided money to help them settle in other states.

Life for a free black person was often dangerous. They could be re-enslaved for breaking laws, being in debt, or being homeless. In Monroe County in 1829, eight free black people were sold into slavery for not paying their taxes. Free black people also had to carry papers proving their status, or they could be fined or imprisoned. Enslaved people who were away from their owner's property had to carry a written pass, or they could be stopped by slave patrols.

The American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society was active from 1816 until the end of the Civil War. Their goal was to create an African republic where former enslaved people could live freely, a freedom they couldn't fully experience in the United States. Slave owners often supported this idea because they wanted free black people to leave, believing they encouraged and helped enslaved people escape.

However, most black people strongly opposed the idea of "returning to Africa." They felt they were no more African than white Americans were British. Due to lack of money and ships, only a small number of former enslaved people reached Liberia. For example, from West Virginia, only 184 black people emigrated to Liberia over about 25 years, even though there were 18,000 enslaved people in 1860. Some believed the colonization project was just a trick to make it seem like a solution to slavery was being found, when its real goal was to keep slavery going.

West Virginians Emigrate to Liberia

The first people from West Virginia to emigrate to Liberia were from Berkeley County. Isaac Stubblefield, his wife, and three children sailed in 1829. Their journey was sponsored by Edward Colston, a nephew of Chief Justice John Marshall. In the 1830s, women from the Washington-Blackburn families of Jefferson County helped groups of freed people emigrate to Liberia, collecting donations for their supplies.

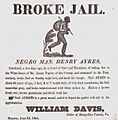

In 1836, William Johnson of Tyler County tried to send 12 freed people to Liberia. He didn't have the same connections as the wealthy families, so the Society asked for donations. He accompanied the new emigrants to Washington, D.C., and then to Norfolk, where they sailed for Liberia in 1840.

Virginia passed laws in 1833 and 1850 to encourage free black people to emigrate to Liberia. However, funds were not easily available for newly freed slaves because the legislature didn't want to encourage more people to free their slaves. The bill was partly funded by a yearly tax of one dollar on all free black men between 21 and 55 years old.

A census of Liberia in 1843 showed that few of the early emigrants from West Virginia were still there. The new land and climate were very different, and malaria caused many deaths. Judith Blackburn was upset by the first reports from the former enslaved people, who described a difficult environment with many deaths from malaria.

The late 1850s saw the last groups of emigrants leaving for Liberia from West Virginia. Samson Caesar, a Liberian from West Virginia, wrote about his despair for Liberia's future. He blamed the United States for denying former enslaved people education and training. He believed that if black people had the same opportunities as white people, they would be just as successful.

During this time, a total of 184 free people were transported to Liberia from West Virginia. Most were from Jefferson County (124 people).

The Underground Railroad in West Virginia

The Underground Railroad was a secret network of safe houses and routes that helped enslaved people escape to freedom.

Harper's Ferry Route

Some enslaved people with lighter skin sometimes bought train tickets on the B&O railroad to reach Pittsburgh. Others walked across the narrow panhandle of Maryland to reach Pennsylvania. Many free black people worked with Quakers in this area to help with escapes.

Morgantown Route

Two routes ran through the Morgantown area into Pennsylvania. One path led through Mount Morris, Pennsylvania, to Greensboro, Pennsylvania. The other route left Morgantown and followed the Monongahela River, going through New Geneva, Pennsylvania, to Uniontown. The A.M.E. Zion Church had congregations in both Morgantown and nearby Pennsylvania, which helped with escapes.

Point Pleasant-Parkersburg Route

Enslaved people escaping from central West Virginia could follow the Kanawha River to Point Pleasant. From there, they could follow the Ohio River north to Parkersburg. Across the river from Parkersburg was the Ohio town of Belpre, where a man named Colonel John Stone helped runaways. Fugitives were hidden in Parkersburg by a black woman known as "Aunt Jenny" until they could cross the river.

Wheeling-Wellsburg Route

Wheeling was an important stop for runaways because it was located between Ohio and Pennsylvania. A branch of the Underground Railroad ran between Wheeling and Wellsburg, going east to the Pennsylvania towns of Washington or West Middletown. The McKeever family in West Middletown would hide fugitives in their poultry wagon and drive them to Pittsburgh. The A.M.E. Zion Church in Wheeling also actively helped enslaved people escape to freedom.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 led to many enslaved people being returned to western Virginia. Just before the Civil War, an enslaved person belonging to the Jackson family in Harrison County escaped to Ohio by stealing a horse. However, he was returned under the Act and sold further south. One of the last enslaved people returned under the Act was Sara Lucy Bagby, who escaped to Ohio but was returned to her owner in Wheeling on January 24, 1861. Sara Bagby was freed during the war and moved to Pittsburgh. Enslaved people who ran away and were returned, or were thought to be planning an escape, were often sold.

Slavery During the Civil War

When Union troops invaded West Virginia on May 26, 1861, General George B. McClellan told the people of western Virginia that his army would not interfere with their enslaved people. He even said they would "crush any attempt at insurrection" by enslaved people. However, as the war continued, Union soldiers often considered escaped enslaved people to be "contraband," or spoils of war. Some even joined the United States Colored Troops in the Union army.

The war gave many enslaved people a chance to escape to Ohio and Pennsylvania. Both the Union and Confederate armies forced some men into labor groups to repair railroads and bridges. Without the support of their spouses or former owners, women and children suffered greatly. Enslaved families faced hardship not only from raiding soldiers but also from violent guerrilla fighters. Reaching Union-held territory did not always guarantee freedom.

The war also encouraged enslaved people to revolt. In May 1861, in Lewisburg, an enslaved man named Reuben was found guilty of planning a rebellion. Weapons were found in his cabin, and he was sentenced to be executed.

With Union troops controlling the northern counties of western Virginia, a Unionist government in Wheeling, called The Restored Government of Virginia, decided to create a new state from the western counties. The voters approved this idea on October 24, 1861, and elected members to write a constitution for the new state. One of the main issues was slavery. Most hoped that the federal government would allow statehood without requiring them to end slavery.

The convention did not include a clause to end slavery in the new constitution. Instead, they added a rule forbidding free black people and enslaved people from entering the new state, hoping this would be enough for Congress.

| Ages | Slaves |

|---|---|

| <1 | 354 |

| 1-4 | 1,866 |

| 5-9 | 2,148 |

| 10-14 | 2,072 |

| 15-19 | 1,751 |

| 20-29 | 2,400 |

| 30-39 | 1,589 |

| 40-49 | 1,030 |

| 50-59 | 617 |

| 60-69 | 378 |

| 70-79 | 145 |

| 80-89 | 42 |

| 90-99 | 14 |

| over 100 | 4 |

| unknown | 1 |

The Willey Amendment

Senators Charles Sumner and Benjamin Wade opposed the bill for West Virginia's statehood because it didn't include a plan for ending slavery. On December 31, 1862, President Lincoln signed the West Virginia statehood bill, but only if the new state agreed to some form of emancipation (freeing enslaved people). Waitman T. Willey, a Senator from Virginia (under the Restored Government), wrote an amendment to the constitution that would be voted on by the public. This became known as the Willey Amendment.

The Willey Amendment

The children of slaves born within the limits of this State after the fourth day of July, eighteen hundred and sixty-three, shall be free; and all slaves within this state who shall, at the time aforesaid, be under the age of ten years, shall be free when they arrive at the age of twenty-one years; and all slaves over ten and under twenty-one years shall be free when they arrive at the age of twenty-five years; and no slave shall be permitted to come into the State for permanent residence therin.

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed all enslaved people in Confederate territories not under Union control. This meant that the 48 counties named in the West Virginia statehood bill were exempt, even though many were in rebellion. Later, two more counties, Jefferson and Berkeley, were added to West Virginia. Enslaved people in Berkeley County were also exempt from the Proclamation, but those in Jefferson County were not. So, 49 of West Virginia's 50 counties were exempt.

The Willey Amendment did not free any enslaved people immediately when West Virginia became a state. The first enslaved people would not have been freed until 1867. There was no plan for freedom for any enslaved person over 21 years old. According to the 1860 census, the Willey Amendment would have left at least 40% of West Virginia's enslaved population (over 6,000 people) still enslaved. Many of those under 21 would have remained enslaved for up to 20 more years. The way the amendment was written also created a two-week period where children born to enslaved mothers between June 20, 1863, and July 4, 1863, would still be born into slavery.

The public approved the Willey Amendment, and on April 20, 1863, President Lincoln announced that West Virginia had met all requirements and would become a state on June 20, 1863. In anticipation of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (which would end slavery nationwide), the Wheeling legislature passed a bill ending slavery in West Virginia on February 3, 1865. Even so, the full impact of this law was not immediately clear. Some newspapers were still printing ads for runaway enslaved people in March 1865.

After the War: Reconstruction

The end of the war and the freeing of enslaved people brought both joy and worry. Many people didn't know how to rebuild their lives. Some former slave owners immediately forced all former enslaved people off their land. Others tried to make work contracts or sharecropping agreements. Since few of these agreements were legal, and newly freed people had little access to the legal system, they were often taken advantage of. Lizzie Grant, a former enslaved person from Kanawha County, explained, "Slavery had not ended, no we just went from slaves to peons... They did free them in one sense of the word, but put them in a whole lot worse shape as they turned them loose to make their own way with nothing to make it with... we mostly had to stay with our [former owners] if we got anything... we were forced to stay on as servants, yes, if we expected to live... they still made us do just like they wanted to after the war."

In 1866, the state legislature gave black people the right to testify against white people in court. Before this, they could only testify in cases involving other black people. In 1867, the 14th Amendment was approved, granting citizenship and equal protection under the law.

Because West Virginia was a Union state, it was mostly exempt from the strict rules of Reconstruction. However, the Freedmen's Bureau, an agency created to help former enslaved people, had authority in West Virginia.

The Bureau helped establish schools in Harper's Ferry and Martinsburg in September 1865, and later in Charlestown and Shepherdstown. Except for the school in Martinsburg, the others faced resistance and harassment.

In 1862, Parkersburg became the first city to have a school for black children. By 1867, there were two schools there: one public school with a white teacher and a private school run by R.H. Robinson. Some parents preferred the private school.

The Kanawha Valley had the most black residents outside the eastern panhandle. When the Bureau visited in 1867, they found five schools already started by black citizens. The Bureau found the teaching quality good but the buildings very poor. Local school boards often refused or delayed providing money for new buildings. In Brook's Hollow, the Bureau provided $300, and black residents raised $323 for a new schoolhouse.

At White Sulphur Springs, a local resident donated land for a new building. The Bureau provided $177.10 for supplies, and black residents raised the rest of the money. In Lewisburg, the school board provided a building in early 1868 through the combined efforts of the Bureau and black residents.

The most important achievement of the Freedmen's Bureau was helping to establish Storer College in Harper's Ferry. A grant from John Storer of Stanford, Maine, helped start the college, along with matching funds. The Bureau helped get government buildings and 7 acres of land for the college. The Bureau also contributed $18,000. In December 1868, Congress passed a bill transferring the property to the college.

By 1868, the Ku Klux Klan had organized groups in West Virginia. Lizzie Grant remembered, "There was them KKK's to say that we must do just like our white man tell us, if we did not, they would take the poor helpless negro and beat him up good." In Colliers, a white mob broke up a black political meeting. In Harper's Ferry, a crowd threw stones at a black school.

When the state of West Virginia was created in 1863, most of its citizens did not participate in the decision. At the end of the war, the Wheeling government needed to stay in power. To do this, they took away the civil rights of former Confederates and their supporters. These rights included the right to vote, serve on juries, teach, practice law, or hold public office.

The introduction of the 15th Amendment in 1869, which aimed to give black men the right to vote, also gave disfranchised white men a chance to regain their rights. A federal judge ruled that the 15th Amendment applied to all male citizens, regardless of race. He ordered the arrest of any state official who denied a male resident the right to vote. As a result, thousands of Confederate veterans and supporters were added to the voting lists.

By 1871, the Wheeling government had lost power, and their state constitution was rejected by public vote. A new state constitution was written in 1872. By 1876, seven of the eight successful candidates for state offices, including the governor, had been in the Confederate army.

Although the new constitution guaranteed black people the right to vote and hold public office, it also created separate schools for black and white children. In 1873, the legislature limited jury duty to white men.

Civil Rights Efforts

After the war, some black West Virginians organized politically. In June 1868, a group of 60 black Republicans from several states, including West Virginia, met in Baltimore. They met again in August as the Colored Border State Convention, where West Virginian Adam Howard was chosen as a vice-president. The convention called for a national meeting in January to discuss voting rights. At the National Convention of Colored Men in Washington, D.C., on January 13, 1869, over 200 members met, including Frederick Douglass. The main focus was on gaining the right to vote, but they also discussed issues like work, housing, and education. This convention helped draw Congress's attention to the 15th Amendment, which became law in 1870.

In 1879, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Strauder v. West Virginia that the state had failed to allow black people to serve as jurors, despite its obligations to qualify them for citizenship.

Issues related to slavery continued to appear in legal cases even after the war ended. In 1878, a case went to the state supreme court about enslaved people who had been bought with Confederate money. In 1909, West Virginia claimed the value of enslaved people who had been executed by the Virginia government in a lawsuit about adjusting pre-war debts.

Images for kids

-

African Repository and Colonial Journal, August 1837, describing the efforts of William Johnson of Tyler County to settle his former slaves in Liberia.

-

Routes of the Underground Railroad through West Virginia

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |