History of the Maya civilization facts for kids

The history of the Maya civilization is split into three main time periods: the Preclassic, Classic, and Postclassic. Before these, there was an Archaic Period when the first villages started and farming began. Experts today see these periods as simple ways to organize time, not as signs of the Maya culture getting better or worse. The exact start and end dates for each period can change a bit depending on who you ask.

The Preclassic period lasted from about 3000 BC to 250 AD. Then came the Classic period, from 250 AD to about 950 AD. After that was the Postclassic period, from 950 AD until the mid-1500s. Each of these big periods is also divided into smaller parts:

| Period | Section | Dates | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Archaic | 8000–2000 BC | ||

| Preclassic | Early Preclassic | 2000–1000 BC | |

| Middle Preclassic | Early Middle Preclassic | 1000–600 BC | |

| Late Middle Preclassic | 600–350 BC | ||

| Late Preclassic | Early Late Preclassic | 350–1 BC | |

| Late Late Preclassic | 1 BC – AD 159 | ||

| Terminal Preclassic | AD 159–250 | ||

| Classic | Early Classic | AD 250–550 | |

| Late Classic | AD 550–830 | ||

| Terminal Classic | AD 830–950 | ||

| Postclassic | Early Postclassic | AD 950–1200 | |

| Late Postclassic | AD 1200–1539 | ||

| Contact period | AD 1511–1697 | ||

Contents

Preclassic Period (around 2000 BC – 250 AD)

The Maya civilization first began to develop during the Preclassic period. Experts are still discussing exactly when this era started. Evidence of Maya people living in Cuello, Belize, has been found from around 2600 BC.

Around 1800 BC, settlements were set up along the Pacific coast in the Soconusco region. People there were already growing important Maya foods like corn, beans, squash, and chili peppers. This early time, called the Early Preclassic, was known for communities settling down in one place and for the first use of pottery and clay figures.

Villages Grow into Cities

During the Middle Preclassic Period, small villages started to grow into larger towns and cities. By 500 BC, these cities had big temple buildings decorated with stucco masks, which were sculptures made from a type of plaster, showing faces of their gods.

Nakbe in Guatemala is the oldest well-known city in the Maya lowlands. Its large buildings date back to around 750 BC. Nakbe already had the huge stone buildings, carved monuments, and raised roads (called causeways) that would become famous in later Maya cities. The northern lowlands of Yucatán were also widely settled during this time. By about 400 BC, Maya rulers began to put up stone monuments called stelae to celebrate their achievements and show their right to rule.

Early Maya Writing and Big Cities

In 2005, ancient paintings (murals) were found that showed Maya writing was used much earlier than thought. A developed writing system was already in use at San Bartolo in Guatemala by the 3rd century BC. This shows that the Maya were part of a wider development of writing in Mesoamerica during the Preclassic period.

In the Late Preclassic Period, the huge city of El Mirador grew to cover about 16 square kilometers (6 square miles). It had paved roads, massive pyramid complexes (groups of three pyramids) from around 150 BC, and stelae and altars in its main squares. El Mirador is thought to be one of the first capital cities of the Maya civilization. The swamps in the Mirador Basin seemed to attract the first people to the area, which explains why so many large cities grew up around them.

The city of Tikal, which later became one of the most important Classic Period Maya cities, was already a significant place by about 350 BC, though it wasn't as big as El Mirador. The great cultural growth of the Late Preclassic period ended in the 1st century AD, and many of the large Maya cities from that time were abandoned. No one knows for sure why this happened.

In the highlands, Kaminaljuyu became a major center in the Late Preclassic. It connected trade routes from the Pacific coast with the Motagua River route. It also had more contact with other sites along the Pacific coast. Kaminaljuyu was located at a crossroads, controlling trade routes to the west (to the Gulf coast), north (into the highlands), and along the Pacific coast to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and El Salvador. This allowed it to control the movement of important goods like jade, obsidian, and cinnabar (a red mineral). Within this large trade network, Takalik Abaj and Kaminaljuyu seemed to be the two main hubs. The early Maya style of sculpture spread throughout this network. Takalik Abaj and Chocolá were two of the most important cities on the Pacific coastal plain during the Late Preclassic. Komchen also grew into an important site in northern Yucatán during this period.

Classic Period (around 250–950 AD)

The Classic period is mostly defined by the time when the Maya in the lowlands put up dated monuments using the Long Count calendar. This period was the peak of large building projects and city growth. It also saw many important writings on monuments and great progress in thinking and art, especially in the southern lowland areas. The political setup of the Classic period Maya was like that of Renaissance Italy or Classical Greece. There were many independent city-states, and they were always forming complicated alliances and rivalries.

During the Classic Period, the Maya civilization reached its greatest achievements. The Maya developed a civilization focused on cities and intense farming. It was made up of many independent city-states, with some being more powerful than others. In the Early Classic, cities across the Maya region were influenced by the huge city of Teotihuacan, far away in the Valley of Mexico.

In 378 AD, Teotihuacan strongly influenced Tikal and other nearby cities. They removed Tikal's ruler and put in a new ruling family supported by Teotihuacan. This change was led by a person named Siyaj Kʼakʼ ("Born of Fire"), who arrived at Tikal on January 31, 378 AD. The king of Tikal, Chak Tok Ichʼaak I, died on the same day, which suggests a forceful takeover. A year later, Siyaj Kʼakʼ oversaw the installation of a new king, Yax Nuun Ahiin I. The new king's father was Spearthrower Owl, who had a name from central Mexico and might have been the king of Teotihuacan or Kaminaljuyu. This new ruling family led to a time when Tikal became the most powerful city in the central lowlands.

Rivalries and Alliances

At its peak during the Late Classic, the city of Tikal had a population of well over 100,000 people. Tikal's big rival was Calakmul, another powerful city in the Petén Basin. Both Tikal and Calakmul built large networks of allies and cities that paid tribute to them. Smaller cities that joined one of these networks gained respect from being linked to the top city and had peaceful relations with others in the same network.

Tikal and Calakmul used their alliance networks against each other. At different times during the Classic period, one of these powers would win an important victory over its rival, leading to times of great success and then decline for each.

In 629 AD, Bʼalaj Chan Kʼawiil, a son of the Tikal king Kʼinich Muwaan Jol II, was sent to start a new city 120 kilometers (75 miles) to the west, at Dos Pilas. This was in the Petexbatún region, and it seemed to be an outpost to spread Tikal's power beyond Calakmul's reach. The young prince was only four years old at the time. When the new kingdom was set up, Dos Pilas showed its connection to Tikal by using Tikal's special symbol (emblem glyph) as its own. For the next two decades, he fought loyally for his brother and ruler at Tikal.

In 648 AD, king Yuknoom Chʼeen II ("Yuknoom the Great") of Calakmul attacked and defeated Dos Pilas, capturing Balaj Chan Kʼawiil. Around the same time, the king of Tikal was killed. Yuknoom Cheʼen II then put Balaj Chan Kʼawiil back on the throne of Dos Pilas, but as his own vassal (someone who owes loyalty to a more powerful ruler). In a surprising act of betrayal for someone claiming to be from Tikal's royal family, he then became a loyal ally of Calakmul, Tikal's sworn enemy.

In the southeast, Copán was the most important city. Its Classic-period ruling family was started in 426 AD by Kʼinich Yax Kʼukʼ Moʼ. The new king had strong ties with central Petén and Teotihuacan, and he was likely from Tikal originally. Copán reached its highest point of culture and art during the rule of Uaxaclajuun Ubʼaah Kʼawiil, who reigned from 695 to 738 AD. His rule ended badly in April 738, when he was captured by his vassal, king Kʼakʼ Tiliw Chan Yopaat of Quiriguá. The captured lord of Copán was taken back to Quiriguá and killed in early May 738. It is likely that Calakmul supported this takeover to weaken a strong ally of Tikal. Palenque and Yaxchilan were the most powerful cities in the Usumacinta region. In the highlands, Kaminaljuyu in the Valley of Guatemala was already a large city by 300 AD. In the north of the Maya area, Coba was the most important capital.

The capital cities of Maya kingdoms could be very different in size. This seemed to depend on how many smaller cities were connected to the capital. Rulers of city-states who controlled more subordinate lords could demand more tribute, which was payment in goods and labor. The most common types of tribute shown on Maya pottery were cacao (chocolate beans), textiles (cloth), and feathers.

The Classic Maya civilization was built on a large political and economic network that spread throughout the Maya area and even into the wider Mesoamerican region. The most powerful Classic period cities were in the central lowlands. During this time, the southern highlands and northern lowlands were less important culturally, economically, and politically. Places between these core and less important areas acted as centers for trade.

Monuments and Trade

The most famous monuments are the pyramid-temples and palaces they built in the centers of their greatest cities. At this time, using hieroglyphic writing on monuments became common. These writings left a lot of information, including records of ruling families, alliances, and other interactions between Maya cities. The carving of stone stelae spread throughout the Maya area during the Classic period. Pairs of carved stelae and low round altars are seen as a special sign of Classic Maya civilization. During the Classic period, almost every Maya kingdom in the southern lowlands put up stelae in its ceremonial center.

The expert on Maya writing, David Stuart, first suggested that the Maya saw their stelae as te tun, meaning "stone trees." He later changed his idea to lakamtun, meaning "banner stone." According to Stuart, this might mean the stelae were stone versions of tall flags or banners that once stood in important places in Maya city centers, as shown in ancient Maya graffiti. The main purpose of a stela was to honor the king.

The Maya civilization traded over long distances. Important trade routes went from the Motagua River to the Caribbean Sea, then north along the coast to Yucatán. Another route went from Verapaz along the Pasión River to the trading port at Cancuén. From there, trade routes went east to Belize, north to central and northern Petén, and on to the Gulf of Mexico and the west coast of the Yucatán Peninsula. Important luxury trade goods included jade, fine pottery, and quetzal feathers. More common trade goods might have included obsidian (volcanic glass), salt, and cacao.

Classic Maya Collapse

During the 9th century AD, the central Maya region suffered a major political collapse. This was marked by cities being abandoned, ruling families ending, and activity shifting northward. This decline also meant that monumental inscriptions and large building projects stopped. No single theory fully explains this collapse, but it was likely caused by several things working together. These include constant warfare between cities, too many people leading to severe damage to the environment, and drought (a long period of dry weather). During this time, known as the Terminal Classic, the northern cities of Chichen Itza and Uxmal showed increased activity. Major cities in the northern Yucatán Peninsula continued to be lived in long after the cities of the southern lowlands stopped putting up monuments.

There is evidence that the Maya population grew larger than the environment could support. This led to less fertile farmland, deforestation (cutting down too many trees), and too much hunting of large animals. A 200-year-long drought also seems to have happened around the same time.

The Classic Maya social system was based on the ruler's religious authority, rather than on central control of trade and food. This way of ruling was not well-suited to handle big changes. The ruler's actions were limited to traditional responses, like building more or performing more rituals and warfare. This actually made the problems worse.

By the 9th and 10th centuries, this led to the collapse of the ruling system based on the divine power of the lord. In the northern Yucatán, individual rule was replaced by a ruling council made up of important families. In the southern Yucatán and central Petén, kingdoms generally declined. In western Petén and some other areas, the changes were very bad and led to cities quickly losing most of their people. Within a couple of generations, large parts of the central Maya area were almost completely empty. A relatively quick collapse affected parts of the southern Maya area, including the southern Yucatán Peninsula, northern Chiapas and Guatemala, and the area around Copán in Honduras. The largest cities had populations of 50,000 to 120,000 and were connected to networks of smaller sites. Both the capital cities and their smaller centers were generally abandoned within 50 to 100 years.

By the late 8th century, constant warfare had taken over the Petexbatún region of Petén, leading to the abandonment of Dos Pilas and Aguateca. One by one, many once-great cities stopped carving dated monuments and were abandoned. The last monuments at Palenque, Piedras Negras, and Yaxchilan were dated between 795 and 810 AD. Over the next few decades, Calakmul, Naranjo, Copán, Caracol, and Tikal all became less important. The last Long Count date was carved at Toniná in 909 AD. Stelae were no longer put up, and people started living in abandoned royal palaces. Mesoamerican trade routes changed and no longer passed through Petén.

Postclassic Period (around 950–1539 AD)

The great cities that ruled Petén had become ruins by the beginning of the 10th century AD, marking the start of the Classic Maya collapse. Even though it was much smaller, a significant Maya presence remained into the Postclassic period after the major Classic period cities were abandoned. The population was especially gathered near permanent water sources. Unlike earlier times when the Maya region shrank, abandoned lands were not quickly settled again in the Postclassic.

Activity shifted to the northern lowlands and the Maya Highlands. This might have involved people moving from the southern lowlands, as many Postclassic Maya groups had stories about migrating. Chichen Itza became important in the north in the 8th century AD, at the same time as cities were being abandoned in the south. This highlights the economic and political reasons behind the collapse. Chichen Itza became probably the largest, most powerful, and most diverse of all Maya cities. Chichen Itza and its nearby Puuc cities declined sharply in the 11th century, which might be the final part of the Classic period collapse. After Chichen Itza's decline, the Maya region didn't have a single dominant power until the city of Mayapan rose in the 12th century. New cities appeared near the Caribbean and Gulf coasts, and new trade networks were formed.

Changes in Cities and Government

The Postclassic Period was marked by a series of changes that made its cities different from those of the Classic Period. The once-great city of Kaminaljuyu in the Valley of Guatemala was abandoned after being continuously lived in for almost two thousand years. This was a sign of changes happening across the highlands and nearby Pacific coast. Cities that had been in open locations were moved, seemingly because of a lot of warfare. Cities began to be built on hilltops that were easier to defend, surrounded by deep ravines. Sometimes, walls and ditches were added to the natural protection. Walled defenses have been found at several sites in the north, including Chacchob, Chichen Itza, Cuca, Ek Balam, Mayapan, Muna, Tulum, Uxmal, and Yaxuna.

One of the most important cities in the Guatemalan Highlands at this time was Qʼumarkaj, also known as Utatlán. It was the capital of the powerful Kʼicheʼ Maya kingdom. The governments of Maya states, from Yucatán to the Guatemalan highlands, were often organized as joint rule by a council. However, in practice, one member of the council could act as the supreme ruler, with the other members serving him as advisors.

Mayapan was abandoned around 1448, after a time of political, social, and environmental problems that in many ways were similar to the Classic period collapse in the southern Maya region. The abandonment of the city was followed by a long period of warfare in the Yucatán Peninsula, which only ended shortly before the Spanish arrived in 1511. Even without a dominant regional capital, the early Spanish explorers reported wealthy coastal cities and busy marketplaces.

Maya Groups Before the Spanish Arrived

During the Late Postclassic, the Yucatán Peninsula was divided into many independent areas. They shared a common culture but had different ways of organizing their societies and governments. Two of the most important areas were Mani and Sotuta, which were enemies.

When the Spanish arrived, the groups in the northern Yucatán peninsula included Mani, Cehpech, Chakan, Ah Kin Chel, Cupul, Chikinchel, Ecab, Uaymil, Chetumal, Cochuah, Tases, Hocaba, Sotuta, Chanputun (modern Champotón), and Acalan. A number of groups lived in the southern part of the peninsula, including the Petén Basin, Belize, and surrounding areas. These included the Kejache, the Itza, the Kowoj, the Yalain, the Chinamita, the Icaiche, the Manche Chʼol, and the Mopan. The Cholan Maya-speaking Lakandon people controlled land along the rivers that flow into the Usumacinta River, covering eastern Chiapas and southwestern Petén.

Just before the Spanish conquest, the highlands of Guatemala were ruled by several powerful Maya states. In the centuries before the Spanish arrived, the Kʼicheʼ had built a small empire covering a large part of the western Guatemalan Highlands and the nearby Pacific coastal plain. However, in the late 15th century, the Kaqchikel rebelled against their former Kʼicheʼ allies and started a new kingdom to the southeast, with Iximche as its capital. In the decades before the Spanish invasion, the Kaqchikel kingdom had been steadily weakening the Kʼicheʼ kingdom. Other highland groups included the Tzʼutujil around Lake Atitlán, the Mam in the western highlands, and the Poqomam in the eastern highlands. The central highlands of Chiapas were home to several Maya peoples, including the Tzotzil, who were divided into many provinces, and the Tojolabal.

Contact Period and Spanish Conquest (1511–1697 AD)

In 1511, a Spanish ship was wrecked in the Caribbean, and about a dozen survivors landed on the coast of Yucatán. A Maya lord captured them, and most were killed, though two managed to escape. From 1517 to 1519, three different Spanish expeditions explored the Yucatán coast and fought several battles with the Maya people living there.

After the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan fell to the Spanish in 1521, Hernán Cortés sent Pedro de Alvarado to Guatemala. Alvarado had 180 horsemen, 300 foot soldiers, 4 cannons, and thousands of allied warriors from central Mexico. They arrived in Soconusco in 1523. The Kʼicheʼ capital, Qʼumarkaj, fell to Alvarado in 1524.

Soon after, the Spanish were invited as allies into Iximche, the capital city of the Kaqchikel Maya. Good relations didn't last because the Spanish demanded too much gold as tribute, and the city was abandoned a few months later. This was followed by the fall of Zaculeu, the Mam Maya capital, in 1525. Francisco de Montejo and his son, Francisco de Montejo the Younger, started a long series of military campaigns against the cities of the Yucatán Peninsula in 1527. They finally finished conquering the northern part of the peninsula in 1546.

This left only the Maya kingdoms of the Petén Basin independent. In 1697, Martín de Ursúa launched an attack on the Itza capital Nojpetén. This last independent Maya city then fell to the Spanish.

Persistence of Maya Culture

The Spanish conquest took away most of the main features of Maya civilization. However, many Maya villages stayed far away from Spanish colonial rule and mostly continued to manage their own affairs. Maya communities and families kept their traditional daily life. The basic Mesoamerican diet of corn and beans continued, though farming improved with the introduction of steel tools. Traditional crafts like weaving, pottery, and basket making continued to be produced. Community markets and trade in local products went on long after the conquest. Sometimes, the colonial government even encouraged the traditional economy to get tribute in the form of pottery or cotton cloth, though these were usually made to European designs. Maya beliefs and language proved hard to change, despite strong efforts by Catholic missionaries. The 260-day tzolkʼin ritual calendar is still used today in modern Maya communities in the highlands of Guatemala and Chiapas. Millions of people who speak Mayan languages still live in the areas where their ancestors developed their civilization.

Investigation of the Maya Civilization

From the 1500s onwards, Spanish soldiers, priests, and administrators knew about pre-Columbian Maya history and beliefs. Catholic Church officials wrote detailed accounts of the Maya to help with their efforts to convert them and bring them into the Spanish Empire. The writings of 16th-century Bishop Diego de Landa, who famously burned many Maya books, contain many details about Maya culture. These include their beliefs, religious practices, calendar, parts of their hieroglyphic writing, and oral history. This was followed by various Spanish priests and colonial officials who left descriptions of ruins they visited in Yucatán and Central America. These early visitors knew that the ruins were connected to the Maya people living in the region.

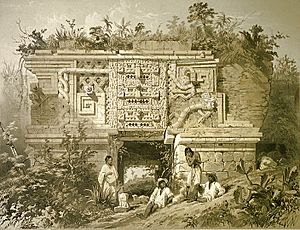

In 1839, American traveler and writer John Lloyd Stephens, who knew about earlier Spanish investigations, set out to visit Uxmal, Copán, Palenque, and other sites with English architect and artist Frederick Catherwood. Their illustrated stories about the ruins sparked a lot of public interest in the region and its people, bringing the Maya to the world's attention. Their account was picked up by 19th-century collectors like Augustus Le Plongeon and Désiré Charnay, who thought the ruins were built by Old World civilizations or from sunken continents. The later 19th century saw the recording and recovery of historical accounts of the Maya, and the first steps in understanding Maya hieroglyphs.

The last two decades of the 19th century saw the start of modern scientific archaeology in the Maya region, with the careful work of Alfred Maudslay and Teoberto Maler. Sites like Altar de Sacrificios, Coba, Seibal, and Tikal were cleared and documented. By the early 20th century, the Peabody Museum was funding excavations at Copán and in the Yucatán Peninsula, and artifacts were being secretly taken from the region to the museum's collection. In the first two decades of the 20th century, progress was made in understanding the Maya calendar and identifying gods, dates, and religious ideas. Sylvanus Morley started a project to document every known Maya monument and hieroglyphic inscription. In some cases, he recorded texts from monuments that have since been destroyed. The Carnegie Institution sponsored excavations at Copán, Chichen Itza, and Uaxactun, laying the modern groundwork for Maya studies. From the 1930s onwards, archaeological exploration increased greatly, with large-scale excavations across the entire Maya region.

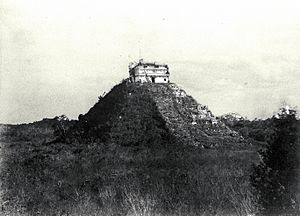

However, in many places, Maya ruins have been covered by the jungle, making it hard to see structures just a few meters away. To find unknown ruins, researchers have started using satellite imagery to look at visible and near-infrared light. Because the monuments were built with limestone, they changed the chemical makeup of the soil as they broke down. Some plants that like moisture are completely missing, while others were killed or changed color.

In the 1960s, the famous Maya expert J. Eric S. Thompson suggested that Maya cities were mainly empty ceremonial centers that served people living spread out in the forest, and that the Maya civilization was ruled by peaceful astronomer-priests. These ideas came from the limited understanding of Maya writing at the time. They began to fall apart with major breakthroughs in understanding the writing in the late 20th century, led by Heinrich Berlin, Tatiana Proskouriakoff, and Yuri Knorozov. As new discoveries in understanding Maya writing were made from the 1950s onwards, the texts showed the warlike activities of the Classic Maya kings, and the idea of the Maya as peaceful could no longer be supported. Detailed surveys of Maya cities showed evidence of large populations, ending the idea of empty ceremonial centers.

In 2018, archaeologists found 60,000 unknown structures with the help of a new laser technology called 'lidar' in northern Guatemala. The project used Lidar technology over an area of 2,100 square kilometers (810 square miles) in the Maya Biosphere Reserve in the Petén region of Guatemala. Unlike earlier beliefs, thanks to these new findings, archaeologists now think that 7-11 million Maya people lived in northern Guatemala during the late Classic period, from 650 to 800 AD. Lidar technology digitally removed the tree canopy to show ancient remains and revealed that Maya cities like Tikal were bigger than previously thought. Houses, palaces, raised roads, and defensive walls were uncovered because of Lidar. According to archaeologist Stephen Houston, it is "one of the greatest advances in over 150 years of Maya archaeology."

The capital of Sak Tz’i’ (an Ancient Maya kingdom), now named Lacanja Tzeltal, was discovered by researchers led by anthropology professor Charles Golden and bioarchaeologist Andrew Scherer in Chiapas, in the backyard of a Mexican farmer, in 2020.

Many buildings used by the people for religious purposes were found. "Plaza Muk’ul Ton" or Monuments Plaza, where people used to gather for ceremonies, was also uncovered by the team.

See also

In Spanish: Historia maya para niños

In Spanish: Historia maya para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |