History of the potato facts for kids

The potato is a super important vegetable that first grew in what is now southern Peru and northwestern Bolivia. People started growing potatoes there between 8000 and 5000 BCE. Some experts think potatoes might have been grown in South America as far back as 10,000 years ago!

The oldest potato remains found by archaeologists were in Ancón, central Peru, from about 2500 BC. Besides actual potato pieces, ancient people in Peru also made ceramic pots shaped like potatoes. This shows how important potatoes were to them. Over time, potatoes spread all over the world and became a main food in many countries.

Potatoes arrived in Europe before the end of the 1500s. They came through two main places: Spain around 1570, and the British Isles between 1588 and 1593. One of the first times potatoes were written about was in a delivery note from 1567, sent between Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and Antwerp. By the 1800s, potatoes had become a major food in Europe, especially in Ireland. They were great because they didn't spoil quickly, filled people up, and were cheap!

Contents

Potato's Early Life in South America

Finding Ancient Potatoes

The oldest potato pieces found by archaeologists were in Ancón, central Peru, dating back to 2500 BC. There's also evidence from stone tools that potatoes might have been around as early as 3400 BC. But it's hard to be sure because potatoes don't last long in the ground. Potatoes from about 2000 BC were also found in the Casma Valley of Peru. Even older potatoes, from 800-500 BC, were found at Chiripa near Lake Titicaca.

Archaeological findings also show that potatoes became more and more popular as a food during the time of the Tiwanaku people in the Andes (from 1500 BC to 500 BC). Boiled and steamed potatoes became common instead of just soups. Scientists studied ancient human skeletons and found that potatoes were a big part of the Andean diet, along with quinoa (a grain) and animals like llamas. Later, during the Inca period, people ate more maize (corn), but potatoes were still very common.

Besides actual potato remains, ancient Peruvian artists also made ceramic pots shaped like potatoes. These pots showed potatoes in three ways: as clear pictures of the vegetable, as human-like figures, or as a mix of both. This shows that potatoes were very important to the people who lived in the Altiplano region. The Moche people were fascinated by the potato's bumpy and unusual shape. They often showed potatoes in their art as strange animals or humans, creating a feeling they called mundo hororroso (a scary world). Their potato art often explored ideas about physical differences and strange visions.

How South Americans Used Potatoes

In the Altiplano region, potatoes were the main source of energy for the Inca Empire, and for the people who lived there before and after the Incas. Andean people cooked potatoes in many ways, just like we do today: mashed, baked, boiled, and in stews.

They also made a dish called papas secas by boiling, peeling, and chopping potatoes. Another food they made was toqosh, which was fermented potatoes. They also ground potatoes into a pulp to make a starch called almidón de papa.

But the most important potato product was chuño. To make chuño, farmers would let potatoes freeze overnight and then thaw them in the morning. They repeated this process to make the potatoes soft. Then, they squeezed out the water, making the potatoes much lighter and smaller. Chuño could be stored for years without needing a refrigerator! This was super helpful during times of famine or bad harvests. It was also the main food for the Inca armies because it kept its flavor and lasted a long time. The Spanish also fed chuño to the silver miners who dug up a lot of wealth for the Spanish government in the 1500s.

Potatoes were also a main food for most Mapuche people before Europeans arrived, especially in southern and coastal areas where maize didn't grow well. The Chono tribe grew potatoes in the Guaitecas Archipelago in Patagonia. This was the southernmost place where farming happened in South America before Columbus.

How Potatoes Spread Around the World

Potatoes Arrive in Europe

Sailors coming back to Spain from the Andes, carrying silver, likely brought maize (corn) and potatoes to eat on their journey. Historians believe that any leftover potatoes were planted when they reached land. It's thought that potatoes arrived in Europe before the end of the 1500s. They came through Spain around 1570, and through the British Isles between 1588 and 1593. Records show potatoes being shipped from the Canary Islands to Antwerp in 1567. Potatoes were likely brought to the Canary Islands from South America around 1562.

Europeans in South America knew about potatoes by the mid-1500s, but they didn't want to eat them at first. The Spanish thought potatoes were only for the native people. In England, potatoes also became known as a food for the working class. In 1553, a book called Crónica del Peru mentioned seeing potatoes in places like Quito. Basque fishermen from Spain used potatoes on their long voyages across the Atlantic in the 1500s. They brought potatoes to western Ireland when they landed there to dry their fish.

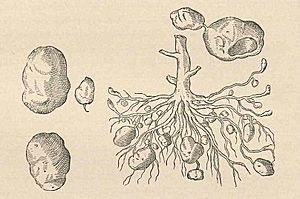

Some people say that Sir Francis Drake or Walter Raleigh's employee Thomas Harriot brought potatoes to England. In 1588, a botanist named Carolus Clusius drew a picture of a potato he called "Papas Peruanorum." By 1601, he reported that potatoes were commonly used in northern Italy for both animal food and for people to eat.

At first, potatoes were grown in Europe more for their flowers than for food. In 1573, they were first eaten in a hospital in Seville, Spain. After King Philip II received potatoes from Peru, he sent them to the pope, who then sent them to his ambassador in the Netherlands. Clusius got his potatoes from this ambassador and planted them in different cities. He is known for helping to spread the potato widely in Europe.

The Spanish Empire was huge in Europe, and they brought potatoes for their armies to eat. Farmers along the way started growing the crop because potatoes were less likely to be stolen by armies than grains that grew above ground. In many parts of Northern Europe, potatoes were first grown only in small gardens. People were afraid of them, thinking they might be poisonous like some other plants in herb gardens. They even called potatoes "the devil's apples" because they grew underground.

However, after 1750, leaders in France and Germany encouraged farmers to plant potatoes. Potatoes then became a very important main food in northern Europe. Food shortages in the 1770s helped people accept potatoes. Also, the climate was changing during the Little Ice Age, and traditional crops weren't growing as well. Potatoes could still grow reliably during colder years when other crops failed.

In France, potatoes were introduced to some regions by the late 1500s. By the late 1700s, a gardening book called Bon Jardinier said: "There is no vegetable about which so much has been written and so much enthusiasm has been shown... The poor should be quite content with this foodstuff." By the 1800s, potatoes had largely replaced turnips and rutabagas.

Potatoes greatly changed European populations and society. They produced about three times more calories per acre than grain. They were also more nutritious and could grow in many different soils and climates. This greatly improved farming in the early modern era. Even so, it took a while for people to fully accept them.

Perhaps the first place in Europe to grow potatoes widely was Ireland in the early 1600s. By the 1700s, the Irish population grew very quickly, and people there ate almost only potatoes. Potatoes spread to England soon after Ireland. By the late 1700s, a writer named Sir Frederick Eden said that potatoes were a regular food at every meal for both rich and poor people (except breakfast). By 1715, potatoes were common in many parts of Europe, including Germany and France. In warmer places like Portugal, Spain, and Italy, maize (corn) became more popular than potatoes.

Potatoes in Africa

It's thought that potatoes came to Africa with European colonists, who ate them as a vegetable. Records from 1567 show that the Canary Islands were the first place outside of Central and South America where potatoes were grown. Like in other places, farmers in Africa at first didn't want to grow potatoes. They thought potatoes were poisonous. Also, since colonists promoted them as a cheap food, potatoes became a symbol of foreign rule.

In former European colonies in Africa, potatoes were eaten only sometimes at first. But as more were grown, they became a main food in some areas. Potatoes became more popular during wartime because they could be stored in the ground. By the mid-1900s, they were a well-known crop. Today, in Africa, potatoes are a common vegetable or a co-staple food.

In the higher regions of Rwanda, potatoes have become a new main food crop. Before the 1994 Rwandan genocide, people there ate a lot of potatoes, even more than in some Western European countries. Farmers have recently started growing potatoes as a cash crop (a crop grown to sell) after getting new types of potatoes from workers returning from Uganda and Kenya.

Potatoes in Asia

Potatoes spread widely after 1600 and became a major food in Europe and East Asia. When potatoes arrived in China around the end of the Ming dynasty, they were at first a special food for the emperor's family. After the mid-1700s during the Qing dynasty, China's population grew a lot. This meant they needed more food. Farmers also moved around more, which helped potatoes spread quickly across China. Potatoes adapted well to the local conditions.

In Indonesia, different root crops were adopted over time. Sweet potatoes were common by the 1670s. Potatoes and yam beans were common by the 1780s. Cassava became popular from the 1860s.

In India, an English traveler named Edward Terry mentioned potatoes in 1675. The gardens in Surat and Karnataka had potatoes in 1675, according to another traveler. The Portuguese brought potatoes, which they called 'Batata', to India in the early 1600s. They grew them along the western coast. British traders brought potatoes to Bengal, calling them 'Alu'. By the late 1700s, potatoes were grown across the northern hill areas of India. Potatoes arrived in Tibet by the 1800s through trade routes from India.

Potatoes in North America

Early settlers in Virginia and the Carolinas might have grown potatoes from seeds or tubers from Spanish ships. But the first definite potato crop in North America was brought to New Hampshire in 1719 from Derry. These plants came from Ireland, so the crop became known as the "Irish potato." Thomas Jefferson once said that he believed the "Irish potato" was not native to North America but came from Ireland.

It wasn't until after 1750 that potatoes were widely planted in eastern North America, similar to Europe. In 1812, the Russian-American Company planted potatoes at Fort Ross, which was the first time in western North America. Potatoes were planted in Idaho as early as 1838. By 1900, Idaho was producing over a million bushels of potatoes. Before 1910, potatoes were stored in barns or root cellars. But by the 1920s, special potato cellars or barns were used. U.S. potato production has steadily increased. Most of the crop comes from Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Colorado, and Maine.

Potatoes Become a Main Food in Europe

A French doctor named Antoine-Augustin Parmentier studied potatoes a lot. In 1774, he wrote a book showing how nutritious they were. King Louis XVI and his wife, Marie Antoinette, really promoted the new crop. Marie Antoinette even wore a headdress made of potato flowers to a fancy party! France's potato harvest grew a lot, helping the population grow without running out of food.

Even though potatoes were known in Russia by 1800, they were mostly grown in small gardens. But after a grain shortage in 1838–39, farmers and landowners in central and northern Russia started planting potatoes in their fields. Potatoes produced two to four times more calories per acre than grain. They eventually became the main food supply in Eastern Europe. Boiled or baked potatoes were cheaper than rye bread, just as healthy, and didn't need to be ground into flour.

In Germany, Frederick the Great, the king of Prussia, worked hard to convince farmers to grow potatoes. In 1756, he even issued an official order telling people to plant them. This "potato order" called the new vegetable "a very nutritious food." Frederick was sometimes known as the Kartoffelkönig ("potato king").

Throughout Europe, the potato was the most important new food in the 1800s. It had three big benefits: it didn't spoil quickly, it filled people up easily, and it was cheap. The crop slowly spread across Europe. For example, by 1845, potatoes covered one-third of Ireland's farmland. Potatoes made up about 10% of the calories Europeans ate. Along with other foods from the Americas, potatoes helped European populations grow.

In Britain, the potato helped the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s. It was a cheap source of calories and nutrients that city workers could easily grow in small backyard plots. Potatoes became popular in the north of England, where there was a lot of coal. So, the potato-driven population boom provided many workers for the new factories. Some even said the potato was as important as iron for changing history! The potato-starch industry in the Netherlands grew quickly in the 1800s.

In Ireland, poor farmers who rented small plots of land were the ones who expanded potato farming. A single acre of potatoes and the milk from one cow was enough to feed an entire Irish family. It was a simple diet, but it was healthy and filling for the poor rural population. Often, even poor families grew enough extra potatoes to feed a pig, which they could then sell for money.

However, because there weren't many different types of potatoes being grown, the crop was very open to disease. In the early 1800s, a potato disease called blight (Phytophthora infestans) started spreading in the Americas. It then spread to Europe in the 1840s. Because there was so little genetic variety in European potatoes, the crops were even more easily destroyed. Northern Europe saw huge crop losses for the rest of the 1800s.

Ireland was especially hit hard because poor people, especially in western Ireland, depended almost entirely on this one crop. The "Lumper" potato, which was widely grown in western and southern Ireland before and during the Great Famine, was bland and not very resistant to the blight. But it produced large crops and usually gave enough calories. When the blight arrived in 1845, it quickly turned ready-to-harvest potatoes into a rotten mush. The Irish Famine between 1845 and 1849 was a terrible food shortage that led to about a million deaths from hunger and diseases. It also caused many people to leave Ireland and move to Britain, the U.S., Canada, and other places. About one million Irish people left during the famine years. Ireland's population didn't recover until the 1900s, when it was less than half of what it was before the famine (8 million people).

Modern Potato Research

By the 1960s, the Canadian Potato Research Centre in Fredericton, New Brunswick, was one of the top potato research places in the world. It started in 1912. In the 1930s, it began focusing on creating new types of potatoes that could resist diseases. In the 1950s and 1960s, as the French fry industry grew in New Brunswick, the center focused on developing potatoes for that industry. By the 1970s, their potato research was wider than ever, but it focused more on helping the potato industry rather than just general potato farmers. Potatoes are Canada's most important vegetable crop. They are grown in all of Canada's provinces, with Prince Edward Island leading the way.

Starting in the 1960s, a Chilean scientist named Andrés Contreras began collecting old, forgotten types of potatoes in the Chiloé Archipelago and San Juan de la Costa. These potatoes were mostly grown in small gardens by older women and passed down through families. In 1990, he led an expedition to find potatoes in the Guaitecas Archipelago, which was the southernmost place where farming happened before Columbus. Contreras's collection became the basis for the gene bank of Chilean potatoes at the Austral University of Chile in Valdivia. Contreras also helped local communities by improving potato types for small-scale farming.

Today, potatoes are very popular because they are so versatile. They can be used to make many different kinds of dishes!

See also

In Spanish: Historia cultural de la papa para niños

In Spanish: Historia cultural de la papa para niños