Iberian ship development, 1400–1600 facts for kids

For hundreds of years, daily life and wars in the Iberian Peninsula were closely connected. Small armies were always ready. This constant fighting meant people needed to be good at sailing, build better ships, and organize their sea power. So, the kingdoms of Aragon, Portugal, and later Castile, focused their efforts on the sea.

Because of their location, countries in the Iberian Peninsula had better access to the sea than most of Europe. This helped them become skilled sailors and traders. They were eager to explore and were close to the riches of Africa and the Mediterranean Sea. New ships and technology grew because of trade, military needs, and religious goals.

By 1411, Portugal stopped fighting Castile. In 1415, Portugal took over Ceuta, its first colony overseas. The crusades helped Portugal make new trade deals and alliances. Portugal wanted to protect its coast from raids and secure its base in the Mediterranean. They could attack Muslim trade ships while also trading in gold, slaves, and ivory. As a seafaring people in the southwest of Europe, the Portuguese became leaders in exploration during the Middle Ages.

Instead of crossing land through Castile and Aragon, Portugal used the sea to reach other European markets. They sent goods by sea to England, Flanders, Italy, and Hanseatic league towns. This was a smart choice given their strong sailing skills.

One big reason for sea exploration was to find new ways to trade with the East. The old land routes, like the Silk Road, were very expensive. These routes were first controlled by Venice and Genoa. Then, after 1453, the Ottoman Empire took over Constantinople, blocking European access. For many years, ports in the Spanish Netherlands made more money than the colonies. Goods from Spain, the Mediterranean, and the colonies were sold there. Wheat, olive oil, wine, silver, spices, wool, and silk were big businesses.

The gold brought back from Guinea made the Portuguese, and their neighbors like Spain, very excited about trade. These voyages of discovery were not just for religion or science. They also brought a lot of wealth.

Portugal learned a lot from its connections with nearby Iberian and North African Muslim states. Because of these links, Portugal gained many skilled mathematicians and experts in naval technology. Portuguese and foreign experts made important discoveries in math, map-making, and ship design.

In 1434, the first group of African slaves arrived in Lisbon. For a long time, slave trading was a very profitable part of Portuguese trade. Throughout the 1400s, Portuguese explorers sailed along the coast of Africa. They set up trading posts for many goods like firearms, spices, silver, gold, and slaves.

Portugal developed unique ships because of its important location. It was a bridge between Northern and Southern waters. When there was no need to improve ships, their development slowed down. People mainly used two types of ships: longships and roundships (dromonds). Longships used oarsmen and were often warships. Roundships used sails and carried cargo.

These early ships worked for their jobs but were not perfect. The galley (longship) had to be light for men to row it and long enough for many men. This meant it could not carry enough supplies for long trips. It worked well near ports but not for long ocean voyages. The roundship could carry more supplies and handle rougher weather. But it was very slow, making it almost useless for war. These ships were good for their intended uses, but not for exploring distant seas.

If Iberian sailors wanted to travel further, they needed better ship technology. Kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula saw ships from both Northern and Southern states. Mediterranean sailors often used triangular lateen sails and navigation tools. Lateen sails were great because they could move a ship even with light breezes. Atlantic sailors used stronger, heavier Baltic cogs. These cargo ships had a single square sail and rudders at the back. They were built to handle stormy waters.

Contents

Why Iberian Ships Became Great

The culture of the Iberian Peninsula was different from the rest of Europe during the Middle Ages. This was because of contact with Moorish culture and the Pyrenees mountains, which isolated them. So, their military ideas, equipment, and tactics were unique.

Their armies could move quickly over long distances. This allowed them to return home fast after battles. Wars were often fought in border areas, where skirmishers lived. These were people used to raiding enemy villages. On land, these wars mixed European methods with tactics from Muslim raiders in Al-Andalus. They used small groups to surprise opponents with ambushes.

In Mombasa, Vasco de Gama even used piracy. He looted Arab merchant ships, which usually had no weapons or heavy cannons.

There were challenges, like depending on wood to build ships. Portugal's geography helped it with good access to water and suitable coasts for ports. But they had few forests for trees. To help shipbuilders, the government gave money to certain areas. In Lisbon, for example, the tax on royal forest trees was removed for ships over one hundred tons. Fewer trees meant builders had to be very careful. This led to new ships being built with the latest technology, helping Portugal expand by sea.

Spain had an easier time building ships because it had more forests than Portugal. This doesn't mean Spain had endless trees. But it allowed for more types of ships. Spain's leaders did not force people to cut down trees. They wanted to save trees for firewood and for cattle to eat and shelter under. The Spanish monarchy asked people to plant two seeds for every tree they cut down. But often, people just moved trees to cut-down areas. These trees often died because they couldn't adapt.

It wasn't until the 1560s and 1570s that King Philip II really cared about timber for shipbuilding. He started setting specific numbers of oak trees to be cut in certain areas. Strict laws were enforced by special forest guards who reported directly to the king. This even made some companies complain about being poor. The Spanish were excellent shipbuilders. Later, ships themselves became items for sale. The English bought six galleons from Spain to build their own fleet.

Even with fewer trees, shipbuilding was profitable and encouraged construction. Shipbuilding became a key part of the Spanish economy. Different areas specialized. Seville, for example, was known for repairing ships, making sails, and preparing food and barrels for shipyards. These business interests helped pay for new ship developments. As long as there was a need for better, faster, stronger ships, technology improved. This made it possible for ships to travel further from shore and eventually across entire oceans.

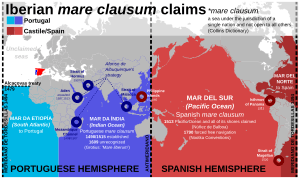

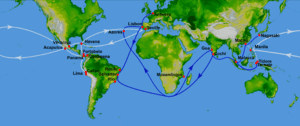

Long before Castile, Portugal had already settled islands in the Atlantic. These included Madeira, the Azores, Cape Verde, and Sao Tome. Portugal also created a sea route around Africa, with many small bases along the way.

With colonies on Atlantic islands and African bases, Portugal had enough forests to build its fleet. It also had money to pay for construction. For example, Madeira island, which means "Wood island," was covered with thick forests when it was found and settled.

Besides exploring coasts, Portuguese ships also went further out to sea. They gathered information about weather and ocean currents. These trips led to the discovery of many islands. These included the Bissagos Islands, Trindade and Martim Vaz, Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago, Fernando de Noronha, Corisco, Elobey Grande, Elobey Chico, Annobón Island, Ascension Island, Bioko Island, Falkland Islands, Príncipe Island, Saint Helena Island, Tristan da Cunha Island, and the Sargasso Sea.

Knowing about wind patterns and currents, like the trade winds and oceanic gyres in the Atlantic, was key. Sailors also learned to find their latitude. This led to finding the best ocean route back from Africa. This route involved crossing the Central Atlantic to the Azores. It used the winds and currents that spin clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere because of atmospheric circulation and the Coriolis effect. This made it easier to get to Lisbon. This maneuver was called the "volta do mar" (return of the sea). In 1565, applying this idea in the Pacific Ocean helped Spain create the Manila Galleon trade route.

However, there were also challenges to Iberian power. When sailing up rivers in Africa or meeting native people in the New World, both groups had easy-to-move canoes. These canoes could put a lot of pressure on the Portuguese and Spanish. Natives could sail close to larger ships, attack them with projectiles, and then escape before the Iberian ships could get into a good fighting position.

How Ship Design Changed

The ship that truly started the first phase of discoveries along the African coast was the Portuguese caravel. Iberian sailors quickly adopted it for their merchant fleets. It was based on North African fishing boats. Caravels were fast and easy to steer. They weighed 50 to 160 tons and had 1 to 3 masts. Their triangular lateen sails allowed them to sail against the wind. The caravel was especially good at changing direction.

Their main downsides were limited space for cargo and crew. But this didn't stop their success. At first, limited space was fine for exploration ships. Their "cargo" was the new information explorers found, which didn't take up much room. Famous caravels include Berrio and Caravela Annunciation. Columbus also used them on his voyages.

Long ocean trips led to bigger ships. "Nau" was an old Portuguese word for any large ship, especially merchant ships. Because of pirates along the coasts, naus started being used in the navy. They were given cannon ports, and their size was then judged by how many cannons they had. The carrack or nau had three or four masts. It had a high, rounded back with large castles at the front and back, and a bowsprit at the front. The Portuguese first used it, then the Spanish. They were also changed to handle more sea trade. They grew from 200 tons in the 1400s to 500 tons. In the 1500s, they usually had two decks, castles at the front and back, and two to four masts with overlapping sails. Voyages to India in the 1500s used carracks, which were large merchant ships with high sides and three masts with square sails. Some reached 2,000 tons.

Merchants were interested in these ships because they wanted profitable trade. They weren't dreaming of sailing across vast oceans at first. Merchants were agents of change. They wanted stronger ships that could carry the most cargo efficiently. Traders wanted large ships because they were harder to attack and could carry many goods cheaply. The problem with these huge ships was that they took a long time to load and unload, which was less profitable. Also, when smaller ships started carrying cannons, large ships became vulnerable. These ships often cost about US$2 million to build today. What's important is that need led to change. By the 1400s and 1500s, merchants started preferring smaller ships. They went from heavy to lighter sailing ships. This was also when people realized ships could explore further from the coasts.

Ship changes depend on their purpose. Technology doesn't just appear without a need. What started as business trips eventually became voyages of discovery. The desire for distant trade meant that better ships were needed. They needed stable ships that a few sailors could control. They had to be small enough to move easily along coasts and in rivers. But they also needed to be big enough to carry supplies and trade goods over long distances. New ship designs were needed for merchants. As ships improved, people realized they could be used for exploration. Once people wanted to explore, ships changed their function too. Exploration ships had one main job: to carry an explorer's findings. They didn't need to carry a merchant's goods or a warrior's guns. This was a huge realization. It meant ship engineers now had a specific goal for their new projects.

They started adapting the Mediterranean roundship, which used a single, square rig on the mainmast. They slowly increased the cargo space. By the 1400s, ships clearly changed from having one rig to many. They also started relying more on cannons. This shows a good mix between commercial and military ships. Technologies were shared more easily. This made regional differences in ships less noticeable. Textbooks might list many names for ships from this century. But in reality, many of these ships were basically the same. With a common goal for ships—exploring new lands and expanding the crown—ships were designed more uniformly, and common patterns appeared.

By the 1400s and 1500s, the main ships used were the caravels and naus (carrack). Caravels are special because they "evolved." They started as small, open boats used by coastal merchants and fishermen. Once the boat was used for more than just trade and fishing, people realized it needed to be built for the sea, not just for cargo. The nau was built with more beams. It was larger and seen as a "workhorse." It could carry settlers, weapons, tools, and supplies. The nau was very different from the caravel mainly because it was more useful, even if it wasn't as fast as the caravel. These ships helped Spain and Portugal divide the world between them. This advanced technology, built on past ideas, allowed for more expansion and exploration of unknown waters without limits.

Caravels: How They Changed for Exploration

The name "caravel" might come from the Greek word "Καραβος," meaning "light vessel." The caravel was a famous ship in the 1400s and 1500s. The Portuguese used it for their voyages of discovery, and Christopher Columbus used it for his daring trip west. It was a small ship, part of the roundship family, but more graceful than other ships of its time. It was faster, more capable, and better for any task needing speed and quick turns.

Caravels had square backs, castles at the front and back, and fairly high sides. They had a bowsprit and usually four masts. It's hard to describe the exact rigging because it changed depending on the time and country. Early caravels didn't have square sails. But later, square sails were used on the front mast for sailing with the wind or in bad weather. The most common rigging was a four-mast ship with a square-rigged front mast leaning far forward. It had a round top and three lateen-rigged masts that got smaller in size. Sometimes, the mainmast also had a round top like the front mast. Another type of caravel had four masts, but lateen and square sails were arranged differently. The first and fourth masts had lateen sails, while the second and third masts had square sails. These different types of ships changed based on exploration needs. Most of them were around eighty tons.

Caravels were designed to be better than older ships. They were made for quick and shallow trips. At first, they traveled short distances and for short times. As voyages got longer, caravels started relying on larger supply ships that would join them. They needed a ship that could carry many supplies and also have the speed of a caravel. This led to the invention of naus.

Caravels and naus formed an unbeatable team for explorers. Columbus used one nau, the La Santa María, and two caravels, the La Pinta and La Niña, on his trip across the Atlantic. This team was successful because it had weapons for defense and was very easy to maneuver. They were like floating batteries of firepower. Vasco da Gama saw Columbus's success. In 1497, he followed Dias's path to India using two newly built naus, each weighing one hundred tons, and one caravel, weighing fifty tons. By 1502, he went on another journey using ten naus and five armed caravels to go to the East African coast. These new ships easily destroyed Islamic dhows. Following this pattern, Magellan had a fleet of five naus, though only one made it back.

It's helpful to think of caravels in three stages: early caravels, exploring caravels, and fleet caravels. Before Spain and Portugal started their big discoveries, caravels were small. They couldn't leave the sight of shore. Some didn't even have decks. The next stage was the exploring caravels. As Iberian sailors looked for more than just local trade, they experimented with ships. They wanted to bring gold, slaves, ivory, and spices into the Iberian world.

Before the caravel was perfected, Iberian sailors used other ships: the barcha and barineles. These were common in the 1400s. They were used to sail around Cape Bojador, which took twelve years and fifteen voyages to complete. Both ships were used to go further down the African coast. The barcha weighed about twenty-five to thirty tons. It was partly decked and was a sailing ship, though it could be rowed by its fourteen to fifteen men. The barinel was similar but a bit larger. These ships were important then, but they were slow and hard to manage for exploration. When these ships returned from Africa, it was hard for them to fight the northeast winds. Even adding square sails and oars didn't make them fast enough.

Technology changes when people demand it. There was a need for larger crews, more supplies, and more trade goods. Plus, people wanted more maneuverability. When people realized that barchas and barineles weren't meeting their needs, they started using parts of the caravel. They saw that the caravel's shallow draft (how deep it sits in the water) was good for river trade. That's when they understood that the caravel, if changed correctly, would be good for deeper exploration. A ship that could sail against the wind was a must. So, triangular sails, which allowed better use of the wind, were used to improve the exploration ship.

The Portuguese built better ships by mixing what they had seen. The caravela Latina combined their Arab conquests with what Iberians had seen in Egypt. This made a ship that was longer, larger, lighter, and more advanced than anything used before. A typical caravel was over fifty tons, twenty to thirty meters long, and six to eight meters wide. The lateen sails were rigged on masts that were two-thirds tall, and sometimes there was no bowsprit. These changes made it possible to increase speed and crew size. But it meant less cargo space and war capabilities. People learned that what worked for sailing up the coast of Africa wasn't useful for Atlantic voyages. There was a demand for better technology, so the caravela redonda was designed. It had three masts for better steering, a new rig for ocean sailing, and square sails. These improvements made it possible to sail the entire Atlantic with less uncertainty.

These first exploration ships were not the end of the caravel's journey. The caravela redonda kept getting bigger. Its rigging system also became more complex. The caravel now had three or four masts, a bowsprit, and topsails. It also included a crow's nest. These changes were another phase for caravels. By this time, they were called caravelas de armada. This means they were owned by the state or used by military commanders. A variation was the caravela de mexerguerira. This was a messenger ship used to send orders within the fleet. Ships kept changing because they all had different purposes.

Caravels are almost always known for their lateen sails. Yet, with the caravela en la modal Andalucia, the lateen sails were dropped. Its front castle made the bow higher. These ships allowed for a different kind of movement that was better for the Atlantic Ocean. Spain was a strong power on the Atlantic and Mediterranean. This was because it knew how to adapt its ships to fit their purpose and the environment. Whether it was galleys for war or a different ship for exploration. By the end of the 1600s, caravels were no longer the main ship for exploration. They remained for fishermen in Galicia. New ships like the pataches started to replace them because they were fast, small, and good for scouting.

Naus: The Workhorse Ships

As great as the caravel was, its light build meant it was sensitive to rough ocean conditions. As journeys got longer, explorers needed more from their ships. So, the caravel got a new partner: the nau. This ship was designed to carry more weapons and cargo. It also kept good speed and strength. The hull (body) and rigging were more advanced than earlier ships. This made sailing easier on the ocean. This design was not totally new from the caravel; it was an improved version. It could sit high in the water, a mixed idea from earlier roundships. This made the whole ship roomier. These ships had front masts and topsails with a crow's nest. They still mixed lateen mizzens (sails at the back) and square mainsails. There was a need for a more seaworthy ship that still had the benefits of the caravel, so the nau was engineered.

In English books, naus are often confused with carracks. Carracks were common military ships in Britain in the early 1400s. But carracks were smaller ships, not good for rough seas or carrying a lot of freight.

Galleons: Warships of the Sea

The seas carried more than just explorers. Trade pushed new technologies to improve ships. But another reason was for military purposes. Military conquest was a strong motivation. The scale of war grew hugely in the 1500s. Countries needed to show their military strength to prove they could stay independent. Military power was also used for expansion and control. One of the best ships for this was the galleon. It was mainly used as a warship. It was built in the 1500s and 1600s. Besides being warships, galleons also carried treasure and cargo from the Americas.

It's important to see how the galleon differed from other ships like the capital ship. It was made to work better in war. For example, it had fewer decks, which made it more graceful in the water and easier for sailors to handle. This doesn't mean it was perfect. It was large and clumsy. As learned in 1588, these ships were easily outmaneuvered by the English navy's lighter and faster ships. Galleons had three levels, while great ships had four. Another difference was the shape of the front. The galleon did not have a long, sticking-out forecastle like many larger ships of that time. Instead, the galleon's forecastle ended at its back. It had a long, thin front part, similar to a galley, that stuck out forward. The transom (flat back part) of the stern was square, and the poop deck (deck at the very back) was narrow.

In Spain and Portugal, there were more variations. For example, the skids were meant to strengthen the sides. The front and mainmasts had round tops. They could carry courses and topsails, plus one or two lateen mizzens. In short, "the galleon had three masts and square sails. It usually had two decks, and its main cannons were on the sides." These ships were unique then. They were made specifically for war. Because that was their job, they were built to be most effective at sea, meeting the needs of soldiers and sailors.

After the Spanish Armada failed, the galleon lost much of its fame. By the 1600s, new ships were already being designed. These new ships would better fit the needs of the Iberian empires. New demands led to new ship technologies. Shipbuilding changed to fit the times and the goals of the state. However, shipbuilding slowly declined as the Iberian empires faced more problems at home.

See also

In Spanish: Desarrollo naval ibérico (1400-1600) para niños

In Spanish: Desarrollo naval ibérico (1400-1600) para niños

- Age of Discovery

- Caravel

- Galleon

- Carrack