James II of England facts for kids

Quick facts for kids James II and VII |

|

|---|---|

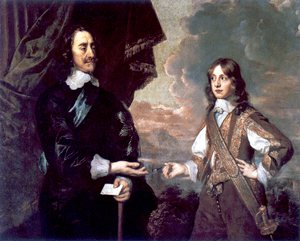

Portrait by Sir Peter Lely

|

|

| King of England, Scotland, and Ireland (more...) | |

| Reign | 6 February 1685 – 23 December 1688 |

| Coronation | 23 April 1685 |

| Predecessor | Charles II |

| Successors | William III & II and Mary II |

| Born | 14 October 1633 (N.S.: 24 October 1633) St James's Palace, London, England |

| Died | 16 September 1701 (aged 67) (N.S.) Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France |

| Burial | Church of the English Benedictines, Paris, France |

| Spouse | |

| Issue more... |

|

| House | Stuart |

| Father | Charles I of England |

| Mother | Henrietta Maria of France |

| Religion |

|

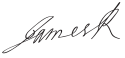

| Signature |  |

James II and VII (born 14 October 1633 – died 16 September 1701) was the King of England and King of Ireland as James II. He was also the King of Scotland as James VII. He became king after his older brother, Charles II, died on 6 February 1685.

James was the last Catholic king of England, Scotland, and Ireland. His time as king is mostly remembered for his efforts to allow different religions to be practiced freely. However, it also involved disagreements about how much power the king should have. He believed in the divine right of kings, meaning he thought his power came directly from God.

He was removed from the throne in 1688 during an event called the Glorious Revolution. This event was important because it showed that the English Parliament had more power than the king.

James became king with a lot of support because people believed in the idea of kings ruling by divine right. However, people were not happy about his Catholic faith. The English and Scottish Parliaments refused to pass his laws that would have given more freedom to Catholics. When James tried to make these laws without Parliament's approval, many people opposed him.

In June 1688, two big events caused a crisis. First, James's son, James Francis Edward, was born. This meant there was a chance for a Catholic royal family to continue ruling, which worried many Protestants. Second, seven bishops were put on trial for speaking against the king. Their acquittal (being found not guilty) showed that James was losing his power in England. People worried that a civil war might start if he stayed on the throne.

Important English leaders then invited William of Orange, James's nephew and son-in-law, to become king. William landed in England on 5 November 1688. Many of James's soldiers left him, and he went into exile in France on 23 December. In February 1689, Parliament decided that James had left the throne empty. They made William and James's daughter, Mary, joint rulers. This showed that Parliament, not birth, was the source of the king's power.

James tried to get his kingdoms back by landing in Ireland in March 1689. There was also a rebellion in Scotland. However, both the Scottish and English Parliaments decided that James had lost his right to the throne and offered it to William and Mary. After losing the Battle of the Boyne in July 1690, James went back to France. He lived there in exile at Saint-Germain, protected by King Louis XIV.

Contents

Early life

Birth and childhood

James was born at St James's Palace in London on 14 October 1633. He was the second son of King Charles I and his wife, Henrietta Maria of France. He was baptized as an Anglican. James was taught by private tutors, along with his brother, the future King Charles II.

When he was three, James was given the honorary title of Lord High Admiral. This job later became a real position when he was an adult. He was also named Duke of York at birth.

Civil War and exile

As the King and the English Parliament fought in the English Civil War, James stayed in Oxford, a place loyal to the King. In 1646, when Oxford surrendered, James was kept at St James's Palace. But in 1648, he managed to escape and went to The Hague.

After his father, Charles I, was executed in 1649, James's older brother was declared King Charles II. Charles II was recognized as king in Scotland and Ireland, but not in England. He had to flee to France.

Life in France

James also found safety in France. He joined the French army and fought under a famous general named Turenne. James gained real battle experience and was known for being brave.

However, France later became allies with Oliver Cromwell, who ruled England at the time. So, Charles II looked to Spain for help instead. Because of this, James had to leave France and Turenne's army in 1656. James then joined the Spanish army and fought against his former French comrades.

During his time in the Spanish army, James became friends with two Irish Catholic brothers. He also grew apart from his brother's Anglican (Protestant) advisors. In 1659, France and Spain made peace. James thought about becoming an admiral in the Spanish navy, but he decided against it. The next year, things changed in England, and Charles II was made King.

Restoration

First marriage and family

After the English government changed, Charles II became King of England again in 1660. James was next in line to the throne, but it seemed unlikely he would become king because Charles was young and expected to have children.

On 31 December 1660, James was also given the Scottish title of Duke of Albany. When he returned to England, James surprised everyone by announcing he would marry Anne Hyde. She was the daughter of Charles's main minister, Edward Hyde. James had promised to marry Anne in 1659, and she became pregnant in 1660. Even though many people, including Anne's father, didn't want them to marry, they had a secret wedding. Then, they had an official ceremony on 3 September 1660.

Their first child was born soon after, but sadly, many of their children died young. Only two daughters survived: Mary (born 1662) and Anne (born 1665). James was a loving father and enjoyed playing with his children. Anne Hyde died in 1671.

Important jobs

After the King returned, James was confirmed as Lord High Admiral. This meant he was in charge of the Royal Navy. He led the navy during two wars against the Dutch (1665–1667 and 1672–1674).

In 1664, Charles gave James some land in America between the Delaware and Connecticut rivers. After the English took control of this area from the Dutch, the main city, New Amsterdam, was renamed New York in James's honor. A fort further north on the Hudson River was renamed Albany, after James's Scottish title. James also led the Royal African Company, which was involved in the slave trade.

In September 1666, James helped fight the Great Fire of London. A witness wrote that James "won the hearts of the people" because he worked tirelessly day and night to help put out the fire.

Becoming Catholic and second marriage

James had learned about Catholicism during his time in France. He and his wife, Anne, became interested in the faith. James secretly became a Catholic in 1668 or 1669. He continued to attend Anglican services until 1676 to keep his conversion a secret.

People in England became worried about Catholic influence in the royal court. In 1673, Parliament passed a law called the Test Act. This law required all government and military officials to take an oath against Catholic beliefs and to receive communion in the Church of England. James refused to do this, so he had to give up his job as Lord High Admiral. This made his conversion to Catholicism public.

King Charles II did not like James's conversion, and he ordered that James's daughters, Mary and Anne, be raised as Protestants. However, Charles allowed James to marry a Catholic princess, Mary of Modena, who was fifteen years old. They were married in a Catholic ceremony on 20 September 1673. Many British people did not trust Catholics and saw Mary of Modena as an agent of the Pope. James was very devoted to his new faith.

Exclusion Crisis

In 1677, James agreed, though unwillingly, to his daughter Mary marrying the Protestant William of Orange. William was also James's nephew. Despite this Protestant marriage, fears about a Catholic king continued. Charles II and his wife had no children, which meant James was still next in line.

A former clergyman named Titus Oates made up a story about a "Popish Plot" to kill Charles and make James king. This false story caused a lot of anti-Catholic fear across the country.

In England, a politician named the Earl of Shaftesbury tried to stop James from becoming king. Some members of Parliament even suggested that the crown should go to Charles's illegitimate son, James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth. In 1679, Charles II dissolved Parliament to prevent a law (the Exclusion Bill) from passing that would have removed James from the line of succession. Two more Parliaments were elected but were also dissolved for the same reason.

This "Exclusion Crisis" led to the development of England's two main political parties: the Whigs, who supported the bill, and the Tories, who opposed it. James was not removed from the line of succession, but he was asked to step back from making important decisions in the government.

James then left England for Brussels. In 1680, he was sent to Scotland to help control the government there. He returned to England when Charles became very ill. The fears about the "Popish Plot" eventually faded, but James's relationships with many in Parliament remained difficult.

Return to favor

In 1683, a plan was discovered to kill Charles and James and start a revolution. This plot, called the Rye House Plot, failed. Instead, it made people feel sorry for the King and James. Several important Whigs were involved, including the King's illegitimate son, the Duke of Monmouth. Monmouth confessed but later changed his story.

Charles reacted by cracking down on Whigs. He took advantage of James's renewed popularity and invited him back to the Privy Council in 1684. Even though some in Parliament were still worried about a Catholic king, the threat of removing James from the throne had passed.

Reign

Becoming King

Charles II died in 1685. He had no legitimate children, so his brother James became King. He was James II in England and Ireland, and James VII in Scotland. At first, most people supported his becoming king, and there was public happiness about the smooth transfer of power.

James wanted to be crowned quickly. He and his wife were crowned at Westminster Abbey on 23 April 1685. The new Parliament, which met in May 1685, was friendly towards James. James worked harder as king than his brother had, but he was less willing to compromise when his advisors disagreed. Parliament gave James a lot of money for life, including taxes from trade.

Two rebellions

Soon after becoming king, James faced two rebellions. One was in southern England, led by his nephew, the Duke of Monmouth. The other was in Scotland, led by the Earl of Argyll. Both Monmouth and Argyll started their plans from Holland. James's nephew and son-in-law, William of Orange, did not stop them from gathering supporters.

Argyll sailed to Scotland and gathered soldiers mainly from his own family group. His rebellion was quickly defeated, and he was captured on 18 June 1685. He was executed soon after.

Monmouth's rebellion was planned with Argyll's, but it was more dangerous for James. Monmouth declared himself King on 11 June. He tried to gather more rebels but could not get enough to defeat James's army. Monmouth's rebellion was defeated at the Battle of Sedgemoor. James's forces quickly scattered the rebels. Monmouth was captured and executed at the Tower of London on 15 July. Many rebels were sent away to work in the West Indies after harsh trials. About 250 rebels were executed. These rebellions made James more determined against his enemies and more suspicious of the Dutch.

Religious freedom and king's power

To protect himself from more rebellions, James wanted to make his army bigger. This worried his subjects because it was not traditional to have a large professional army during peacetime. Even more concerning was James's use of his royal power to allow Catholics to lead some army groups without taking the oath required by the Test Act.

When Parliament, which had supported him before, objected to these actions, James closed Parliament in November 1685. It never met again during his reign. James wanted to remove the laws that punished Catholics in all three of his kingdoms. He allowed Catholics to hold high positions in the government. He also welcomed the Pope's representative to London, the first time this had happened since the reign of Mary I.

In May 1686, James tried to get a court ruling that said his power to ignore Acts of Parliament was legal. He removed judges who disagreed with him. The court case, Godden v. Hales, confirmed his power, with most judges agreeing with him.

In 1687, James issued the Declaration of Indulgence. In this declaration, he used his power to stop the laws that punished Catholics and Protestant Dissenters (non-Anglicans). He tried to get support for this policy by traveling around England. He said that people should not argue about different religious opinions, just as they would not argue about different skin colors. He also gave some religious freedom in Scotland.

In 1688, James ordered that the Declaration of Indulgence be read in every Anglican church. This made the Anglican bishops very upset. James also angered Anglicans by allowing Catholics to hold important positions at the University of Oxford. He tried to force a Protestant college to elect a Catholic-leaning person as their president, which went against their rights.

James then tried to fill Parliament with his supporters so they would remove the Test Act and other laws against Catholics. He removed officials who opposed his plan and appointed new ones. He asked officials if they would support repealing the Test Act and the Declaration of Indulgence. Many who said no were removed from their jobs. He also tried to change local governments to include more Catholics and other non-Anglicans.

Glorious Revolution

In April 1688, James again ordered Anglican clergy to read the Declaration of Indulgence in their churches. Seven bishops, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, asked the King to rethink his religious policies. They were arrested and put on trial for speaking against the king.

Public worry grew even more when Queen Mary gave birth to a Catholic son, James Francis Edward, on 10 June. Before this, James's only possible successors were his two Protestant daughters. So, Protestants thought his pro-Catholic policies might only be temporary. But with a Catholic son, a permanent Catholic royal family seemed possible. Some influential Protestants even claimed the baby was not really the Queen's.

On 30 June 1688, a group of seven Protestant nobles invited William, Prince of Orange, to come to England with an army. By September, it was clear William planned to invade. James refused help from the French King Louis XIV, fearing the English would oppose French involvement.

When William arrived on 5 November 1688, many Protestant officers, including Churchill, left James and joined William. James's own daughter, Princess Anne, also joined William. James lost his courage and decided not to attack William's army, even though his army was larger. On 11 December, James tried to escape to France, supposedly throwing the Great Seal of the Realm (a symbol of royal authority) into the River Thames. He was captured but later released and allowed to escape to France on 23 December. His cousin and ally, Louis XIV, welcomed him and gave him a palace and money.

William called a special Parliament to decide what to do about James's escape. Parliament did not officially remove him from the throne. Instead, they declared that James, by fleeing to France and getting rid of the Great Seal, had effectively given up the throne. This meant the throne was empty. To fill it, James's daughter Mary was declared Queen, and she would rule jointly with her husband William, who would be King. The Parliament of Scotland also declared that James had lost the throne.

The English Parliament passed a Bill of Rights that criticized James for misusing his power. It listed his abuses, such as stopping the Test Acts, putting the Seven Bishops on trial, having a large army in peacetime, and giving harsh punishments. The Bill also stated that no Catholic could ever become King or Queen of England, nor could any English monarch marry a Catholic.

Later years

War in Ireland

With help from French soldiers, James landed in Ireland in March 1689. The Irish Parliament did not follow the English Parliament's example. It declared that James was still King and passed a law against those who had rebelled against him. James also encouraged the Irish Parliament to pass a law for religious freedom for all Catholics and Protestants in Ireland.

James tried to build an army in Ireland, but he was defeated at the Battle of the Boyne on 1 July 1690. William arrived and personally led an army to defeat James and regain English control. James fled to France again, leaving Ireland and never returning to any of his former kingdoms. Because he left his Irish supporters, James became known in Ireland by a nickname meaning "James the Coward."

Return to exile and death

In France, James lived in the royal palace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. His wife and some of his supporters, mostly Catholics, fled with him. In 1692, James's last child, Louisa Maria Teresa, was born.

Some of James's supporters in England tried to kill William III in 1696 to put James back on the throne, but the plan failed. After Louis XIV made peace with William in 1697, he stopped offering much help to James.

In his last years, James lived a very religious and simple life. He wrote advice for his son on how to rule England, suggesting that Catholics should hold certain important government and army positions.

James died from an illness on 16 September 1701 at Saint-Germain-en-Laye. His body was placed in a triple coffin in a church in Paris.

Succession

James's younger daughter Anne became Queen when William III died in 1702. The Act of Settlement said that if the line of succession from the Bill of Rights ended, the crown would go to a German cousin, Sophia, Electress of Hanover, and her Protestant heirs. Sophia was a granddaughter of James VI and I. So, when Anne died in 1714, the crown went to George I, Sophia's son.

James's son, James Francis Edward, was recognized as King by Louis XIV of France and James's remaining supporters, known as Jacobites. They called him "James III and VIII." He led a rebellion in Scotland in 1715, but it failed. Jacobites rebelled again in 1745, led by James II's grandson, Charles Edward Stuart, but they were also defeated. Since then, there have been no serious attempts to restore the Stuart family to the throne.

Images for kids

-

Henri de La Tour d'Auvergne, Viscount of Turenne, James's commander in France

-

Battle of the Boyne between James II and William III, 11 July 1690, Jan van Huchtenburg

-

Tomb of James II in the parish church of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, commissioned in 1828 by George IV when the church was rebuilt.

See also

In Spanish: Jacobo II de Inglaterra para niños

In Spanish: Jacobo II de Inglaterra para niños