Peter Kropotkin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Peter Kropotkin

|

|

|---|---|

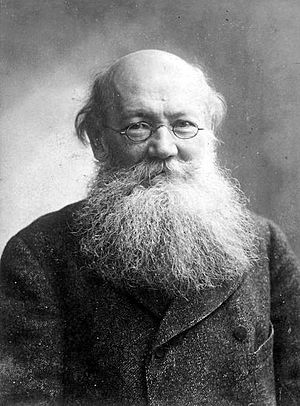

Kropotkin c. 1900

|

|

| Born |

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin

9 December 1842 Moscow, Russian Empire

|

| Died | 8 February 1921 (aged 78) Dmitrov, Russian SFSR

|

| Education |

|

|

Notable work

|

|

| Spouse(s) | Sofia Ananyeva-Rabinovich |

| Era |

|

| Region |

|

| School | |

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

|

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Unit | Corps of Pages |

| Commands held |

|

| Signature | |

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (born December 9, 1842 – died February 8, 1921) was a famous Russian thinker and activist. He was a socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, and philosopher. Kropotkin believed in a system called anarcho-communism.

He was born into a rich family that owned land. Kropotkin went to a military school and later became an officer in Siberia. There, he joined several trips to explore the land. He was put in prison in 1874 for his activism but escaped two years later.

For the next 41 years, he lived outside Russia, in places like Switzerland, France, and England. During this time, he gave many talks and wrote books about his ideas and about geography. Kropotkin went back to Russia after the Russian Revolution in 1917. However, he was not happy with the new Bolshevik government.

Kropotkin believed in a decentralized communist society. This means a society without a strong central government. Instead, he imagined communities and businesses run by the people themselves, working together freely. His most famous books include The Conquest of Bread, Fields, Factories, and Workshops, and Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. He also wrote an article about anarchism for the Encyclopædia Britannica.

Contents

Peter Kropotkin's Life Story

Early Years

Pyotr Kropotkin was born in Moscow, Russia. His family was very old and noble, related to the Rurik dynasty that ruled Russia before the Romanovs. His father, Major General Prince Alexei Petrovich Kropotkin, owned a lot of land and nearly 1,200 serfs (people who were like slaves tied to the land). His mother was the daughter of a Cossack general. She passed away in 1846. His father then married Yelizaveta Markovna Korandina in 1848.

When Kropotkin was 12, he decided to stop using his princely title. He was influenced by ideas of republicanism, which means believing in a government where citizens have power, not kings or princes.

In 1857, at age 14, Kropotkin joined the Page Corps in St. Petersburg. This was a special military school for noble children. Only about 150 boys attended this school, which was connected to the royal court.

While in Moscow, Kropotkin became very interested in the lives of ordinary farmers. He worked as a page for Tsar Alexander II. Although he doubted the tsar's "liberal" (open-minded) reputation, Kropotkin was happy when the tsar decided to free the serfs in 1861. In St. Petersburg, he read many books, especially about French history and the ideas of French thinkers called the Encyclopédistes. During these years (1857–1861), new ideas were growing in Russia. Kropotkin was influenced by these new liberal and revolutionary writings.

In 1862, Kropotkin finished first in his class at the Corps of Pages. He joined the Tsarist army. He chose to serve in a Cossack regiment in eastern Siberia. He wanted to "be someone useful." For a while, he was an aide de camp (assistant) to the governor of Transbaikalia. Later, he worked for Cossack affairs for the governor-general of East Siberia.

Exploring Siberia

Kropotkin worked under General Boleslar Kazimirovich Kukel, who was a liberal and a democrat. Kukel knew many Russian political figures who were sent away to Siberia. Kropotkin once warned a writer named Mikhail Larionovitch Mikhailov about police investigations. Mikhailov later gave Kropotkin a book by the French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. This was Kropotkin's first introduction to anarchist ideas.

In 1864, Kropotkin joined a geography trip. He crossed North Manchuria from Transbaikalia to the Amur. Soon after, he joined another trip up the Sungari River into the heart of Manchuria. These trips helped discover important geographical facts. Kropotkin realized he couldn't make real changes in Siberia through his job. So, he decided to focus on scientific exploration, where he was very successful.

Kropotkin kept reading political books, including works by thinkers like John Stuart Mill. These readings, along with his experiences with farmers in Siberia, led him to become an anarchist by 1872.

In 1867, Kropotkin left the army and went back to St. Petersburg. He studied mathematics at the Saint Petersburg Imperial University. He also became the secretary for the geography section of the Russian Geographical Society. His father was unhappy that Kropotkin left the military tradition and stopped supporting him financially.

In 1871, Kropotkin explored the ice deposits in Finland and Sweden for the Society. In 1873, he published an important scientific paper. He showed that old maps were wrong about the physical features of Asia. He proved that the main mountain ranges ran from southwest to northeast, not north to south or east to west. He was offered a high position at the Society, but he turned it down. He felt it was more important to share knowledge with everyone than to make new discoveries himself. So, he returned to St. Petersburg and joined a revolutionary group.

Activism and Exile

In 1872, Kropotkin visited Switzerland and joined the International Workingmen's Association (IWA). However, he didn't like their support for state socialism. Instead, he studied the ideas of the more anarchist Jura federation in Neuchâtel. He spent time with their leaders and became an anarchist.

Back in Russia, Kropotkin joined the Circle of Tchaikovsky, a socialist group. He worked to spread revolutionary ideas among farmers and workers. He also helped connect the group with noble families. During this time, Kropotkin kept his job at the Geographical Society to hide his revolutionary activities.

In March 1874, Kropotkin was arrested and put in the Peter and Paul Fortress prison. This was because of his political work with the Circle of Tchaikovsky. Because he came from a noble family, he received special treatment in prison. He was even allowed to continue his geography work in his cell. In 1876, he presented a report about the Ice Age. He argued that it happened more recently than people thought.

Escape and Life Abroad

In June 1876, Kropotkin was moved to a less secure prison in St. Petersburg. He escaped with help from his friends. After escaping, he and his friends celebrated by eating at a fancy restaurant. They correctly guessed the police wouldn't look for them there. Then, he took a boat to England. After a short stay, he moved to Switzerland and joined the Jura Federation. In 1877, he moved to Paris and helped start the socialist movement there. In 1878, he went back to Switzerland. He edited a revolutionary newspaper called Le Révolté and published many pamphlets.

In 1881, after Tsar Alexander II was killed, Kropotkin was forced to leave Switzerland. He stayed in London for almost a year. He attended an Anarchist Congress in London in July 1881. Other important people there included Marie Le Compte, Errico Malatesta, and Louise Michel. The congress decided that spreading ideas through actions was the way to social revolution.

Kropotkin returned to France in late 1882. Soon, he was arrested by the French government. He was tried in Lyon and sentenced to five years in prison in 1883. This was because he belonged to the IWA. The French government was pressured to release him, and he was freed in 1886. He was invited to Britain by Henry Seymour and Charlotte Wilson. They all worked on Seymour's newspaper The Anarchist. Later, Wilson and Kropotkin started their own anarchist newspaper, Freedom Press, which is still published today. Kropotkin wrote for the paper often. He lived near London, in places like Harrow and Bromley. His only child, Alexandra, was born in Bromley in 1887. He also lived in Brighton for many years. In London, Kropotkin became friends with famous English socialists like William Morris and George Bernard Shaw.

In 1916, during World War I, Kropotkin and Jean Grave wrote a document called Manifesto of the Sixteen. It supported the Allied countries (like Britain and France) winning against Germany. Because of this, many anarchists disagreed with Kropotkin.

Return to Russia and Final Years

In 1917, after the February Revolution, Kropotkin returned to Russia. He had been away for 40 years. Thousands of people cheered when he arrived. He was offered a job as the minister of education in the new government. But he refused, saying it would go against his anarchist beliefs.

He was excited when the Bolsheviks took power in the October Revolution. He said that this revolution showed that a social revolution was possible. He believed it would guide other countries for a long time, just like the French Revolution did.

However, Kropotkin became more and more critical of the Bolshevik government's methods. He felt their strong central control would not lead to true communism. He wrote that Russia was showing "how not to introduce communism."

-

Kropotkin in Haparanda, 1917

Kropotkin moved to the city of Dmitrov in May 1918. He died there from pneumonia on February 8, 1921, at age 78. He was buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow. Thousands of people marched in his funeral procession. Even with Vladimir Lenin's permission, anarchists carried banners with messages against the Bolshevik government. This was the last time anarchists were allowed to protest publicly in Soviet Russia. His friends Emma Goldman and Aron Baron gave powerful speeches.

Remembering Kropotkin

Many places and things have been named after Kropotkin:

- In 1902, the Kropotkin Range (a mountain range) was named after him.

- On April 14, 1921, a town in Russia, Kropotkin, Krasnodar Krai, was named in his honor.

- In 1930, a work settlement (labor camp) called Kropotkin, Irkutsk Oblast, was named after him.

- In 1948, a village in Crimea was renamed Kropotkino.

- In 1957, a subway station in Moscow, Kropotkinskaya, was named after him.

- In 2014, a memorial museum was opened in Dmitrov. It is in the house where Peter Kropotkin lived and died. The museum shows his documents and how his home looked.

Peter Kropotkin's Writings

Kropotkin wrote many books and pamphlets. Here are some of his most well-known works:

Books

- The Conquest of Bread (1892)

- Fields, Factories, and Workshops (1898)

- Memoirs of a Revolutionist (1899)

- Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902)

- The Great French Revolution, 1789–1793 (1909)

Pamphlets

- An Appeal to the Young (1880)

- Anarchist Communism: Its Basis and Principles (1887)

- Law and Authority (1886)

- The Wage System (1920)

- Anarchist Morality (1898)

See also

In Spanish: Piotr Kropotkin para niños

In Spanish: Piotr Kropotkin para niños

- Anarcho-communism

- Golets Kropotkin

- Katorga