Operation Berlin (Atlantic) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Operation Berlin |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of the Atlantic, World War II | |||||||

The German battleship Gneisenau in 1939; she served as the flagship for Operation Berlin |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2 battleships | Large numbers of warships and aircraft | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | 22 merchant ships sunk or captured | ||||||

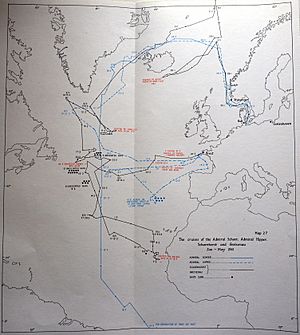

Operation Berlin was a big naval mission by two powerful German battleships, the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, during World War II. From January to March 1941, they sailed across the North Atlantic Ocean. Their goal was to attack Allied ships carrying supplies, as part of the wider Battle of the Atlantic.

The battleships started their journey from Germany. They traveled all over the North Atlantic, sinking or capturing 22 Allied merchant ships. They finished their mission by docking in occupied France. The British military tried to find and attack these German battleships, but they couldn't damage them.

This operation was one of several attacks by German warships in late 1940 and early 1941. The main idea was for the battleships to overpower the escorts of supply ships and then sink many merchant vessels. The British expected these attacks. They started sending their own battleships to protect the convoys (groups of merchant ships traveling together). This plan worked, as the German ships had to give up attacks on convoys several times. However, the Germans did find and attack many unprotected merchant ships.

By the end of the mission, the German battleships had traveled far across the Atlantic. They went from the waters near Greenland all the way to the West African coast. The German military thought the operation was a big success, and most historians agree. This was the last time German warships won against merchant shipping in the North Atlantic. The next big German battleship mission, by the Bismarck in May 1941, ended in defeat. Both Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were later damaged by air attacks in France. They returned to Germany in February 1942.

Contents

Why Operation Berlin Happened

German and British Plans

Before World War II began, the Kriegsmarine (German Navy) made plans to attack Allied merchant ships if war broke out. They planned to use warships to attack ships far out at sea. Submarines and aircraft would attack ships closer to the coasts. The large surface ships were meant to travel widely, make surprise attacks, and then move quickly to new areas. They would get fuel and supplies from special supply ships placed in the ocean beforehand.

Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, who led the German Navy, really wanted to use his battleships in these attacks. He believed the German Navy in World War I made a mistake by not using its battleships aggressively. He didn't want to repeat that error. To protect their small number of battleships and other big warships, the German plans said these ships should only target merchant vessels. They were told to avoid fighting Allied warships.

The Royal Navy (British Navy) knew what Germany planned. They made their own plans to protect merchant shipping using convoys. They also sent cruisers to patrol the waters between Greenland and Scotland. This was where German warships would have to pass to enter the Atlantic. The Home Fleet, which was the main British battle force in the North Atlantic, was in charge of finding and stopping German warships in this area. Admiral John Tovey took command of the Home Fleet in December 1940.

The two Template:Scharnhorst-class battleship, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, were ready for combat when the war started in September 1939. These ships were designed to attack convoys. They had strong armor and were faster than British battlecruisers. Their main guns were 11-inch (28 cm) cannons, which were smaller than the 15-inch (38 cm) guns on most British battleships. The Scharnhorst-class battleships could travel about 9,020 miles (14,516 km) at 17 knots (31 km/h). This wasn't enough for very long missions, so they needed to refuel often from supply ships.

Previous German Attacks

The Scharnhorst-class battleships made their first attack in November 1939. They sank the armed merchant ship HMS Rawalpindi near Iceland on November 23. In February 1940, both battleships, along with the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper, tried to attack convoys near Norway. The British found them quickly, and the Home Fleet tried to stop them. No fighting happened, and the German ships returned to port.

In April 1940, the battleships took part in Operation Weserübung, Germany's invasion of Norway. They were part of a group led by Vice Admiral Günther Lütjens. Their job was to protect the German invasion fleet from British attacks. On April 9, they met the British battlecruiser HMS Renown near the Lofoten Islands. Both German ships were damaged in the fight, so Lütjens pulled back and returned to Germany.

The battleships went out again on June 4 to attack Allied ships near Narvik in northern Norway. This was called Operation Juno. On June 8, they sank the empty troop transport SS Orama and the British aircraft carrier HMS Glorious with its two escorting destroyers. A destroyer hit Scharnhorst with a torpedo during this battle. The damage took six months to fix. On June 20, Gneisenau was torpedoed by the submarine HMS Clyde while sailing from Trondheim. This caused large holes in her front, needing long repairs in Germany.

Scharnhorst was mostly repaired by late November 1940, and Gneisenau was ready for service in early December. The ships trained together in the Baltic Sea during December. By December 23, both battleships were ready for another mission.

In August 1940, German leader Adolf Hitler ordered more attacks on Allied shipping in the Atlantic. The German Navy started sending its big warships into the Atlantic in October. The heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer sailed that month and had a successful mission until March 1941. Admiral Hipper made an unsuccessful mission from Germany into the Atlantic in December. She ended up docking at Brest in occupied France. During her mission, Admiral Hipper attacked Convoy WS 5A on December 25, damaging two transport ships before British cruisers chased her away. Six German merchant raiders also attacked Allied shipping in other oceans.

The attack on Convoy WS 5A showed that raiders were a serious threat in the North Atlantic. So, from early 1941, the British Admiralty started assigning battleships to protect convoys heading to the United Kingdom whenever possible. Convoys traveling west didn't have this protection and were spread out in the middle of the Atlantic.

The Raid Begins

First Try and Breakout

The Scharnhorst-class battleships were chosen for the next mission, called Operation Berlin. Their goal was to get into the Atlantic and work together to attack Allied shipping. Their main target was the HX convoys that regularly sailed from Halifax, Canada, to the United Kingdom. These convoys were vital for supplying the UK. The Germans hoped the battleships could overpower the convoy's escorts and sink many merchant ships.

Admiral Raeder ordered the battleships to end their mission by docking at Brest, France. Brest had become the German Navy's main base in October 1940. The orders for the operation said they should not attack convoys protected by forces of equal strength, like British battleships. This was because the mission would have to stop if Scharnhorst or Gneisenau were badly damaged. Admiral Lütjens, who was the German Navy's fleet commander, led the battle group.

Seven supply ships were sent into the Atlantic before Operation Berlin to support the two battleships. The plans also called for Admiral Hipper to sail from Brest and attack convoy routes between Gibraltar, Sierra Leone, and the United Kingdom. This would cause more damage and hopefully draw British forces away from Lütjens' area.

At this time, the German B-Dienst (signals intelligence service) gave raiders general information about where Allied ships were. However, they usually couldn't give specific, useful information because they couldn't decode intercepted radio messages. Each German raiding ship had a B-Dienst team. This team listened to Allied radio signals and used direction finding to locate convoys and warships. The Germans had little information about when Allied convoys sailed or their exact routes. This made it hard for their ships to find convoys.

Operation Berlin started on December 28, 1940. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau sailed from Kiel that day, with Lütjens commanding from Gneisenau. But the mission had to be stopped before the battleships even reached the Atlantic. Gneisenau was damaged by a storm off Norway on December 30. Lütjens first took the ships into Korsfjord in Norway, planning to repair Gneisenau at Trondheim. However, he was ordered to return to Germany. Both ships reached Gotenhafen on January 2. Gneisenau was then moved to Kiel for repairs. During this time, the battleships also received more small anti-aircraft guns.

Into the Atlantic

Scharnhorst and Gneisenau sailed again from Kiel at 4:00 am on January 22, 1941. They headed north and passed through the Great Belt island chain in German-controlled Denmark that morning. This meant Allied spies on shore could see the battleships. But it was necessary because the waterway had 30 cm (12 inches) of ice. The battle group reached Skagen at the northern tip of Denmark on the evening of January 23. There, they were supposed to meet a group of torpedo boats. These torpedo boats would escort them through minefields between Denmark and Norway. The torpedo boats were slow to leave port, so Lütjens' force didn't continue its journey until dawn on January 25.

The British had learned from German radio signals that major German warships were about to sail. This was from traffic analysis of radio messages. However, Ultra intelligence, which came from breaking German codes, didn't give any information about Operation Berlin. This was because the British couldn't decode the German Navy's codes at that time. On January 20, the Admiralty warned the Home Fleet that another German raid was likely. Admiral Tovey immediately sent two heavy cruisers to strengthen patrols between Allied-occupied Iceland and the Faroe Islands. On January 23, the British naval attaché in Sweden passed on a report from spies in Denmark. They said the German battleships had been seen passing through the Great Belt. This information reached Tovey on the evening of January 25.

The main part of the Home Fleet left its base at Scapa Flow at midnight on January 25. It headed for a position 120 miles (190 km) south of Iceland. This force included the battleships HMS Nelson (Tovey's main ship) and HMS Rodney, the battlecruiser HMS Repulse, eight cruisers, and eleven destroyers. Air patrols of the waters between Iceland and the Faroes were also increased. Some of the Home Fleet's ships had to leave to refuel on January 27. The German Navy had expected this movement. They placed eight submarines south of Iceland to attack the Home Fleet. Only one of these submarines saw any British warships, and it couldn't get into a position to attack.

The German battle group entered the North Sea on January 26. Lütjens thought about refueling from the tanker Adria in the Arctic Ocean before trying to enter the Atlantic. But he decided to go directly south of Iceland after getting a weather forecast that predicted snowstorms there. These conditions would hide the battleships from the British. Just before dawn on January 28, the two German battleships detected the British cruiser HMS Naiad and another cruiser using radar south of Iceland. Naiad's crew saw two large ships six minutes later. Lütjens didn't know if the rest of the Home Fleet was at sea. So, he decided to stop this attempt to enter the Atlantic. The battle group escaped the British by turning northeast and sailing in the Norwegian Sea north of the Arctic circle. One of Gneisenau's two aircraft was sent to Trondheim, Norway, on January 28 with a report. It didn't rejoin its ship. Tovey ordered his cruisers to search for the German ships and moved his battleships and battlecruiser to intercept them, but they didn't find them again. After thinking that Naiad might not have actually seen German warships, Tovey sailed west to protect a convoy and returned to Scapa Flow on January 30. Admiral Hipper left Brest on February 1 to start its own mission.

After refueling from Adria in the Arctic Ocean, far northeast of Jan Mayen island, Lütjens tried to enter the Atlantic through the Denmark Strait north of Iceland. The battleships passed through the straits without being detected on the night of February 3/4. They refueled again from the supply ship Schlettstadt off southern Greenland on February 5 and 6.

Atlantic Operations

First Encounters

From February 6, Lütjens searched for HX convoys. He knew that two British battleships were based in Canada to escort convoys heading east. But he thought they would only cover the first part of the journey before returning. So, the German force operated east of where Lütjens believed the battleship escorts would stop. Convoy HX 106 was sighted at dawn on February 8, about 700 miles (1,100 km) east of Halifax. The Germans didn't know that this convoy's escort included the old battleship HMS Ramillies.

The German battleships split up to attack the convoy. Scharnhorst approached from the south, and Gneisenau from the northwest. Scharnhorst's crew spotted Ramillies at 9:47 am and reported it to the flagship. Following his orders to avoid strong enemy forces, Lütjens canceled the attack. Before being told to stop, Scharnhorst's captain, Kurt-Caesar Hoffmann, brought his ship within 12 miles (19 km) of the convoy. He tried to draw Ramillies away so Gneisenau could attack the merchant ships. This went against the order not to engage warships of equal strength. Lütjens scolded Hoffmann by radio when the two battleships met that evening.

The British battleship's crew saw one of the German ships from a long distance. They mistakenly thought it was probably an Admiral Hipper-class cruiser. Admiral Tovey thought the ship was either Admiral Hipper or Admiral Scheer. He sailed with all available ships to intercept it if it returned to Germany or France. These ships were organized into three strong groups from the evening of February 9. Air patrols were also carried out. Force H, a powerful group based in Gibraltar, was also ordered to protect convoys in the North Atlantic. It sailed from Gibraltar on February 12 and returned on February 25.

On the morning of February 9, the German Navy Group West told Lütjens that intercepted British radio messages showed his ships had been seen the day before. Lütjens decided that the British would now assign strong escorts to all convoys in the area. He chose to stop operations for several days, hoping that attacks by Admiral Hipper would draw British forces elsewhere. The German battle group returned to the waters off southern Greenland and stayed there until February 17. They went through a severe storm on February 12, which damaged many of Scharnhorst's gun turrets. It took three days to fix them. Gneisenau's engines also got sea water in them and needed repairs. The battleships refueled from Schlettstadt and the tanker Esso Hamburg on February 14 and 15. During this time, Admiral Hipper attacked an unprotected convoy on February 12 and sank seven ships. The cruiser then returned to Brest on February 15. Admiral Hipper was supposed to make another raid to help Operation Berlin after loading more ammunition. But this attack was canceled after she damaged a propeller on a sunken barge in Brest's harbor. She couldn't sail until a replacement arrived from Kiel.

The German battle group returned to the route between Halifax and the United Kingdom on February 17. Lütjens decided to operate between the 55th and 45th meridian west. This was west of where he had met HX 106. He correctly believed that Allied shipping there was not as well protected. He hoped to find one of the regular HX convoys or a special convoy that the German naval attaché in Washington, D.C. had reported was expected to leave Halifax on February 15. A merchant ship sailing alone was seen on February 17 but not attacked. Lütjens didn't want to risk alerting any nearby convoys.

Shortly after dawn on February 22, the German battleships found several ships sailing west from a recently spread-out convoy. This was about 500 miles (800 km) east of Newfoundland. They sank five of these ships, totaling 25,784 gross register tons (GRT). A total of 187 survivors were rescued from these ships. The battleships jammed radio transmissions from the merchant vessels as they got closer. However, one of the ships managed to send a sighting report after being attacked by an aircraft launched from the battleships. The signal was received by a radio station at Cape Race in Newfoundland and quickly sent to the Admiralty. This was the first the British knew about the battleships being in the western Atlantic. Lütjens decided that the Allies would now move shipping away from the area and search for his ships. So, he decided to move his operations to the eastern Atlantic and attack the SL convoys that traveled between Sierra Leone and the United Kingdom.

Off West Africa

From February 22, the German ships sailed south. They refueled from the tankers Ermland and Fredric Breme between February 26 and 28. Then they turned southeast. The ships searched for an SL convoy that Lütjens expected to find on March 5, but they didn't succeed. The admiral hoped to use the battleships' aircraft to help the search. But two of the three aircraft were broken beyond repair, and the other was mechanically unreliable. The next day, the battle group met the German submarine U-124 off west Africa. The submarine's commander, Kapitänleutnant Georg-Wilhelm Schulz, gave Lütjens information about the situation in the area.

On March 7, an aircraft from the battleship HMS Malaya spotted the German battleships. Malaya was part of the escort for Convoy SL 67. The German battleships were about 350 miles (560 km) north of the Cape Verde Islands. The battleships saw the convoy later that day, 300 miles (480 km) northeast of the Cape Verdes. But Lütjens decided not to attack it after Malaya was identified. Lütjens told nearby German submarines where the convoy was. A plan was made for the submarines to sink Malaya, and then the battleships would attack the merchant ships. Two submarines attacked the convoy that night and sank five ships. However, they didn't damage Malaya. The German battleships searched for the convoy on March 8, finding it at 1:30 pm. Lütjens tried to attack at 5:30 pm, but he quickly pulled back when Malaya was identified again. The British couldn't chase the faster German ships. Force H sailed from Gibraltar on March 8 and escorted Convoy SL 67 until mid-March.

Back to the North Atlantic

After meeting SL 67, Lütjens decided to return to the convoy route between Halifax and the United Kingdom. While sailing northwest, Scharnhorst sank the unprotected merchant ship SS Marathon on March 9. By this time, both battleships had serious mechanical problems. Some of Gneisenau's extra systems needed maintenance that would take about four weeks to finish. Scharnhorst was in worse condition. Her boiler superheaters were faulty, and the pipes that moved steam around the engines were damaged. The battleships refueled and got supplies from the supply ships Ermland and Uckermark on March 11 and 12. Lütjens kept both supply vessels with the battle group to help search a wider area as they moved north. Together, they could search for ships along a 120-mile (190 km) front.

British Home Fleet ships were sent out again because the German battleships were in the Atlantic. The battleships HMS King George V and Rodney were assigned to escort convoys leaving Halifax on March 17 and 21. Admiral Tovey sailed on Nelson. With the cruiser HMS Nigeria and two destroyers, he took a position south of Iceland to stop any German ships trying to return to Germany.

The German force found Allied merchant ships south of Cape Race on March 15 and 16. On March 15, Gneisenau sank three tankers from Convoy HX 114. Three other tankers, the Bianca, San Casimiro, and Polykarp, were captured. They were sent to German-occupied Europe with German crews on board. The next day, the two battleships sank ten merchant ships from recently spread-out westbound convoys. Many of the Allied ships sent out distress signals. Rodney saw Gneisenau while she was rescuing survivors from one of the ships she had sunk on the evening of March 16. Gneisenau managed to escape from the slower but better-armed British battleship. Rodney's crew saw Gneisenau but didn't identify her. They learned the warship's identity that evening from survivors of a sunken ship. Meanwhile, Admiral Hipper left Brest on March 15 to return to Germany via the North Atlantic and Denmark Strait.

The British changed their plans after the attacks on March 15 and 16. The Admiralty didn't know what Lütjens planned to do next. They thought his force would probably try to return to Germany using one of the routes near Iceland. King George V was sent from Halifax to patrol the area where the merchant ships had been sunk, but she didn't find the German battleships. Tovey strengthened the Home Fleet's cruiser patrols of the possible German return routes. He stayed south of Iceland with most of his fleet. Force H was also ordered by the Admiralty to operate in the North Atlantic. The Royal Air Force's (RAF's) Coastal Command carried out intense air patrols of the Denmark Strait and waters between Iceland and the Faroes from March 17 to 20.

Journey to France

Lütjens had received orders on March 11 to stop operations in the North Atlantic by March 17. This was to help Admiral Hipper and Admiral Scheer return to Germany. To do this, he was to create a distraction between the Azores and the Canary Islands. The German Naval Staff then told him to return his ships to Brest in France. There, they would get ready to join a raid into the Atlantic that the battleship Bismarck and heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen were planning for April. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau refueled again from Ermland and Uckermark on March 18 and set course for France the next day.

At 5:30 pm on March 20, a reconnaissance aircraft from Ark Royal spotted the German battleships sailing northeast. They were about 600 miles (970 km) northwest of Cape Finisterre in Spain. The aircraft's radio was broken, so its crew couldn't report this sighting right away. Lütjens turned north to try and trick the British aircrew about his course. This worked. When the aircraft returned to the carrier, its crew reported that the German ships were heading north and didn't mention their first course. Somerville's ability to act on this report was further delayed because Ark Royal didn't immediately tell him. The Bianca and San Casimiro were also found by Ark Royal's aircraft on March 20. They were scuttled (sunk by their own crews) when Renown approached them.

After Ark Royal reported the sighting, the British tried to find the German battleships again and track them. At this time, the carrier was about 160 miles (260 km) southeast of the Germans. This was too far to launch an immediate attack. Reconnaissance aircraft from Ark Royal searched for the battleships during the night of March 20/21 and the next morning. But they couldn't find them again due to bad weather. Coastal Command reduced its patrols of the waters off Iceland and increased coverage of the areas leading to the Bay of Biscay.

Tovey's force south of Iceland had been joined by the battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth and battlecruiser HMS Hood. On March 21, the Admiralty ordered him to go south at full speed. Several cruisers were also ordered south, a destroyer group sailed from Plymouth, and the RAF's Bomber Command prepared 25 Vickers Wellington bombers to attack the battleships. By this time, the only way for the British ships to stop Lütjens' force before they reached the protection of German aircraft in France was for Ark Royal's aircraft to damage them. This was made impossible by the mishandling of the sighting on March 20 and poor flying weather.

The crew of a Coastal Command Lockheed Hudson aircraft detected the German battleships by radar. They were within 200 miles (320 km) of the French coast on the evening of March 21. By this time, the British couldn't attack them. Also, because Lütjens was taking an evasive course, the British couldn't guess which French port he was heading for. The torpedo boats Jaguar and Iltis escorted the battleships into Brest, where they anchored on March 22. The captured tanker Polykarp docked at Bordeaux two days later. Allied sailors captured from sunken ships were paraded through Brest before being sent to prisoner of war camps in Germany. Admiral Hipper reached Kiel on March 28, and Admiral Scheer docked there two days later.

What Happened Next

Results and Lessons Learned

Operation Berlin was the most successful of the German Navy's surface raiding missions during the entire war. Lütjens' force sank or captured 22 ships, totaling 115,622 gross register tons (GRT). The Allied convoy routes across the North Atlantic were badly disrupted. This made it harder for supplies to reach the United Kingdom. By making the Home Fleet move around, the operation also allowed Admiral Hipper and Admiral Scheer to return safely to Germany.

The German Naval Staff and Admiral Raeder believed that the success of Operation Berlin and other raids in 1940 and early 1941 showed that more such attacks were possible. Raeder traveled to Brest on March 23. He asked Lütjens to lead the next raid with the Bismarck. Several changes were made to surface raiding tactics based on lessons from Operation Berlin. The rule against fighting equally strong forces was relaxed. Battleships could now engage escorting warships while their cruisers attacked the convoy. Since information on convoy routes and times had been unreliable, and Lütjens had trouble finding convoys, they decided to place submarines in key locations to scout for Allied ships. Tactics that worked well, like keeping the battle group's ships together and using supply vessels to search for convoys, were kept.

The British were disappointed with their performance in early 1941. While sending battleships to protect convoys had prevented huge losses, the German surface raiders had greatly disrupted the convoy system and hadn't lost any ships. A key lesson was the need to strengthen patrols in the seas north and south of Iceland. This was to detect German raiders trying to enter the Atlantic. This led to more cruisers being sent to that area.

Historians generally agree that Operation Berlin was a success for Germany. However, some historians, like Richard Woodman, point out that it didn't have a huge impact on the overall war. The number of ships sunk by surface raiders was small compared to those sunk by submarines. Some also argue that sending surface raiders was a flawed strategy. The resources used for these ships might have been better used for submarines.

Historian Stephen Roskill said that the British failed to stop the raiders due to bad luck. But he also noted that the Royal Navy's performance was better than in previous operations. It showed they were now a strong threat to surface raiders. Roskill also observed that assigning battleships to escort convoys "certainly saved two of them from disaster."

Historians agree that Raeder's decision to send the two battleships to Brest was a mistake. Lisle A. Rose noted that by doing so, he "placed the big ships under the thumb of Royal Air Force bombers." It also split the German battle fleet between the Channel and the Baltic. This happened just when new ships meant they needed to concentrate their forces. Rose notes that this error meant Bismarck and Prinz Eugen didn't have the support of the Scharnhorst-class battleships during their mission in May 1941. Raeder admitted his mistake after the war. He said the forces needed to properly defend the battleships at Brest were not available.

Later Operations

Coastal Command aircraft found the two German battleships at Brest on March 28. This was after six days of intense searching of French ports. Once the battleships were confirmed to be in port, the Home Fleet returned to its bases for a short time. The Atlantic convoy system went back to its normal routes. Because of the threat from the ships at Brest, the Home Fleet blockaded the port. They also provided strong escorts to convoys. Submarines were placed off Brest, and Coastal Command watched it closely. The Home Fleet kept three or four naval groups ready at all times to stop the German battleships if they left Brest. Force H was also strengthened and patrolled the routes used by convoys going north and south. Command of the forces operating west of France switched between Tovey and Somerville.

The RAF repeatedly launched large attacks targeting the German battleships at Brest. The first raid happened on the night of March 30/31. On April 6, a British aircraft hit Gneisenau with a torpedo. She was hit by four bombs during another raid on April 10. It took until the end of 1941 to repair the damage from these attacks. Scharnhorst needed repairs to her boilers. This meant she couldn't take part in Operation Rheinübung. That was the mission into the Atlantic by Bismarck and Prinz Eugen in May.

Admiral Lütjens led Operation Rheinübung from the Bismarck. He sank HMS Hood on May 24 during the Battle of the Denmark Strait. He was killed when Bismarck was destroyed by the Home Fleet on May 27. Using Ultra intelligence, the British also sank seven of the eight supply ships that had been sent into the Atlantic to support Bismarck. After this defeat, Hitler forbade further battleship raids into the Atlantic. On June 13, RAF aircraft torpedoed the cruiser Lützow while she was trying to get into the Atlantic. This was the last raid into the Atlantic attempted by the German Navy's heavy warships. As a result, Operation Berlin was the final success against Allied shipping by German warships in the North Atlantic. Submarines became the main part of the German anti-shipping campaign for the rest of the war.

After her boiler repairs were finished, Scharnhorst was moved to La Pallice on July 21. This port was further from British bomber bases and thought to be safer from air attacks. She was hit by five bombs during an air raid on July 24. She needed repairs in Brest that weren't finished until January 15, 1942. Hitler decided in September 1941 to gather the German Navy's surface warships in Norway. So, the Scharnhorst-class battleships were ordered to return to Germany via the English Channel. During the "Channel Dash", they and Prinz Eugen left Brest with a strong air and naval escort on February 11, 1942. Both battleships were damaged by mines, but they reached Germany.

While being repaired at Kiel, Gneisenau was badly damaged by an air raid on the night of February 26/27. She never returned to service. Scharnhorst was sent to Norway in 1943. She was sunk by the Home Fleet on December 26, 1943, during the Battle of the North Cape. This happened as she tried to raid an Allied Arctic convoy.