Pierre Teilhard de Chardin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

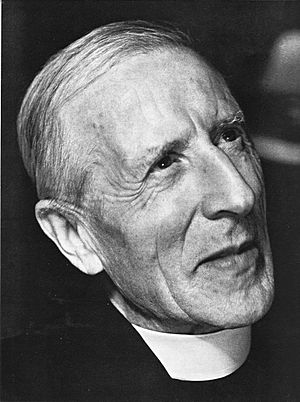

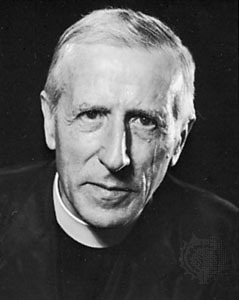

The Reverend Dr.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 1 May 1881 Orcines, Puy-de-Dôme, France

|

| Died | 10 April 1955 (aged 73) New York City, US

|

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (born May 1, 1881 – died April 10, 1955) was a French Jesuit priest, scientist, and philosopher. He was also a paleontologist, which means he studied ancient life through fossils. Teilhard de Chardin was very interested in Charles Darwin's ideas about evolution. He wrote several important books about science, religion, and philosophy.

He helped discover the famous fossil called Peking Man. He also came up with the idea of the Omega Point, which is a future point of maximum complexity and consciousness. With another scientist, Vladimir Vernadsky, he developed the concept of the noosphere. This idea describes the Earth's "thinking layer" formed by human minds and their interactions.

Some of Teilhard's ideas were seen as controversial by the Catholic Church at the time. However, later on, important Catholic leaders like Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis spoke positively about some of his thoughts. Scientists have had mixed reactions to his writings.

During World War I, Teilhard served as a stretcher-bearer, helping injured soldiers. He was recognized for his bravery and received important awards like the Médaille militaire and the Légion d'honneur.

Contents

Life Story

Early Years and Education

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was born on May 1, 1881, in a castle in Orcines, France. He was the fourth of eleven children. His father was a librarian and a keen naturalist, who loved collecting rocks, insects, and plants. He encouraged Pierre to study nature.

Pierre's mother helped him develop his spiritual side. When he was twelve, he went to a Jesuit school. He studied philosophy and mathematics there. In 1899, he joined the Jesuit order. He took his first vows in 1901. In 1902, he earned a degree in literature from the University of Caen.

Around this time, the French government made new rules for religious groups. This meant the Jesuits had to move to the United Kingdom. So, Teilhard continued his studies on the island of Jersey until 1905. Because he was good at science, he was sent to teach physics in Cairo, Egypt, until 1908.

For the next four years, he studied theology in Hastings, England. Here, he combined his scientific, philosophical, and religious knowledge. He was especially influenced by Henri Bergson's book Creative Evolution. This book shaped his ideas about matter, life, and energy. On August 24, 1911, at age 30, he became a Catholic priest.

World War I Service

In December 1914, Teilhard joined the army as a stretcher-bearer. He served in the 8th Moroccan Rifles during World War I. He showed great courage and received several awards for his bravery. These included the Médaille militaire and the Légion d'honneur.

During the war, he wrote down his thoughts in diaries and letters. He later said that the war was a meeting "with the Absolute." In 1916, he wrote his first essay, La Vie Cosmique (Cosmic Life). This essay showed his scientific, philosophical, and spiritual ideas. In 1918, he made his solemn vows as a Jesuit. In 1919, he wrote Puissance spirituelle de la Matière (The Spiritual Power of Matter).

After the war, he studied geology, botany, and zoology at the University of Paris. He earned his science doctorate in 1922. After that, he became an assistant professor at the Catholic Institute of Paris.

Scientific Work

Paleontology Discoveries

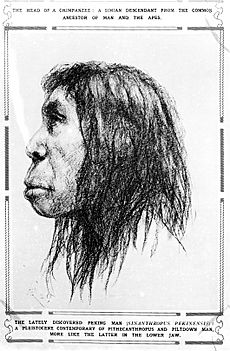

From 1912 to 1914, Teilhard worked in a paleontology lab in Paris. He studied ancient mammals. In June 1912, he was part of the team that found the first pieces of the "Piltdown Man" fossil. This later turned out to be a hoax. Some people have wondered if he was involved, but there is no proof.

A specialist in Neanderthal studies, Marcellin Boule, helped Teilhard focus on human paleontology. In 1913, Teilhard helped excavate a prehistoric painted cave in Spain.

Research in China

In 1923, Teilhard traveled to China. He worked with Father Émile Licent in a science lab in Tianjin. Licent and missionaries collected scientific observations in their free time.

Teilhard wrote essays, including La Messe sur le Monde (Mass on the World), in the Ordos Desert. He continued lecturing at the Catholic Institute in Paris. He also wrote two essays about original sin. The Church asked him to stop lecturing at the Catholic Institute. They wanted him to continue his geology research in China instead.

Teilhard returned to China in April 1926 and stayed for about twenty years. He traveled widely during this time. He lived in Tianjin until 1932, then in Beijing. Between 1926 and 1935, Teilhard went on five geology trips in China. These trips helped him create a general geological map of China.

In 1926–27, Teilhard traveled in the Sanggan River Valley and Eastern Mongolia. He wrote Le Milieu Divin (The Divine Milieu). He also started writing his main work, Le Phénomène Humain (The Phenomenon of Man). However, the Church did not allow Le Milieu Divin to be published in 1927.

In 1926, he joined the team excavating the Peking Man site at Zhoukoudian. He continued as an advisor for the Cenozoic Research Laboratory after it was founded in 1928. Teilhard worked with Chinese paleontologists and other scientists. They discovered that Peking Man could use tools and control fire. Teilhard wrote L'Esprit de la Terre (The Spirit of the Earth).

Teilhard also took part in the "Yellow Cruise" expedition across Central Asia. He joined the Chinese group and traveled to Ürümqi, the capital of Xinjiang.

In 1933, he was told by Rome to leave his post in Paris. Teilhard then explored southern China. He traveled in the Yangtze and Sichuan valleys in 1934. The next year, he explored Guangxi and Guangdong. The museum stopped funding him, saying he worked more for the Chinese Geological Service.

Throughout these years, Teilhard helped build a global network for human paleontology research in Asia. He often visited France or the United States, but always returned for more expeditions.

World Travels and Later Work

From 1927 to 1928, Teilhard was based in Paris. He traveled to Belgium and parts of France. He met new people who helped him with issues he had with the Catholic Church.

He also traveled to Ethiopia and Somalia with a geologist colleague. Then he returned to Tianjin, China. While in China, Teilhard became close friends with Lucile Swan.

In 1930–1931, Teilhard stayed in France and the United States. He said that the biggest event for the future would be the sudden appearance of a shared human consciousness. From 1932 to 1933, he tried to clarify his ideas with the Church. He met a German geologist, Helmut de Terra, at a geology conference in Washington, D.C.

In 1935, Teilhard joined an expedition in northern and central India. He worked with Helmut de Terra to study ancient Indian civilizations. He also visited Java to see the site of Java Man. Another human skull was found there.

In 1937, Teilhard wrote Le Phénomène spirituel (The Phenomenon of the Spirit). He received the Mendel Medal for his work on human paleontology. He gave a speech about evolution and the future of humanity. The New York Times reported that he believed humans came from monkeys. He was supposed to receive another award from Boston College, but it was canceled.

Rome banned his work L’Énergie Humaine in 1939. Teilhard was back in France but got sick with malaria. On his way back to Beijing, he wrote L'Energie spirituelle de la Souffrance (Spiritual Energy of Suffering).

In 1941, Teilhard submitted his most important work, Le Phénomène Humain, to Rome. By 1947, he was forbidden to write or teach about philosophical topics. The next year, he tried to get permission to publish Le Phénomène Humain, but it was again refused. He was also not allowed to teach at the Collège de France. In 1949, permission to publish another work was also refused.

Teilhard was nominated to the French Academy of Sciences in 1950. He was forbidden to attend an international paleontology conference in 1955. In 1957, the Church issued a decree forbidding his works from being kept in libraries or sold in Catholic bookshops.

Main Ideas

Teilhard de Chardin wrote two major books: The Phenomenon of Man and The Divine Milieu. These books were published after he died.

The Phenomenon of Man

In The Phenomenon of Man, Teilhard described how the cosmos (the universe) developed. He explained how matter evolved into life, then into humans, and finally towards a reunion with Christ. He did not take the Book of Genesis literally. Instead, he saw it as a story with deeper, symbolic meanings.

He described the universe evolving from tiny particles to life, then to humans, and then to the noosphere. The noosphere is like a global mind formed by all human thoughts and ideas. He believed this process was moving towards the Omega Point. This Omega Point is a future state where all creation comes together with Christ. Teilhard believed that evolution has a direction and a goal. He thought that evolution leads to more complex and conscious beings.

Teilhard believed that human spiritual growth follows the same rules as material development. He wrote that "everything is the sum of the past" and "nothing is comprehensible except through its history." He saw the universe as constantly creating itself.

He also thought that human evolution is becoming a choice. He pointed out that being alone and left out can stop evolution. This is because evolution needs consciousness to come together. He said that "no evolutionary future awaits anyone except in association with everyone else." He believed that humanity is moving towards a shared mental unity, which he called "unanimization." This unity must be voluntary. Teilhard also stated that "evolution is an ascent toward consciousness."

Cosmic Christ

Teilhard used his ideas about spiritual and material development to describe Christ. He believed that Christ is not just a spiritual figure but also has a physical role. Christ is the organizing force of the universe, the one who "holds together" everything.

For Teilhard, the idea of the Body of Christ is not just about the Church. It is "cosmic," meaning it includes the entire universe. This "cosmic Body of Christ" extends throughout the universe. It includes all things that find their purpose in Christ. Teilhard called this process "Christogenesis." He believed the universe is involved in Christogenesis as it evolves towards its full realization at the Omega Point. This point is when Christ is fully realized.

Relationship with the Catholic Church

In 1925, Teilhard was asked by his Jesuit superiors to leave his teaching job in France. He was also asked to sign a statement taking back some of his ideas about original sin. Teilhard signed the statement and went to China. He chose to stay a Jesuit.

This was the first of several times that Church officials expressed concerns about his writings. The most significant was a "warning" in 1962. This warning said that Teilhard's works had unclear parts and serious errors in their teachings.

However, the Church did not put any of Teilhard's writings on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Forbidden Books). This list of banned books still existed during his lifetime.

Later, important Catholic leaders defended Teilhard's work. Henri de Lubac, who later became a Cardinal, wrote books supporting Teilhard's theology. He said that Teilhard was sometimes unclear but that his ideas were still acceptable within Catholic teaching.

Over the years, many theologians and cardinals spoke positively about Teilhard's ideas. In 2009, a Vatican spokesman said that "no one would dream of saying that [Teilhard] is a heterodox author who shouldn't be studied."

Pope Francis also mentioned Teilhard's ideas in his encyclical Laudato si'. An encyclical is an important letter from the Pope.

However, not everyone agreed. The philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand strongly criticized Teilhard's work. He believed Teilhard's ideas were not compatible with Christianity.

Views from Scientists

Scientists have had different opinions about Teilhard's work.

Julian Huxley

Julian Huxley, an evolutionary biologist, praised Teilhard's ideas. He liked that Teilhard looked at human development within the larger picture of universal evolution. However, he admitted he couldn't agree with all of Teilhard's ideas.

Theodosius Dobzhansky

Theodosius Dobzhansky, another biologist, wrote in 1973 that Teilhard was "one of the great thinkers of our age." He agreed with Teilhard that evolution helps us understand humanity's place in nature.

Daniel Dennett

In 1995, philosopher Daniel Dennett said that most scientists agree Teilhard didn't offer a serious alternative to standard scientific views. He felt Teilhard's unique ideas were confusing.

Steven Rose

Steven Rose wrote that some people see Teilhard as a brilliant mystic. But most biologists see him as "little more than a charlatan."

Stephen Jay Gould

The American biologist Stephen Jay Gould suggested that Teilhard might have been involved in the Piltdown Man hoax. He pointed to some things Teilhard said and his "suspicious silence" about the discovery.

Peter Medawar

In 1961, Nobel Prize winner Peter Medawar wrote a very critical review of The Phenomenon of Man. He called most of it "nonsense." He said Teilhard didn't understand logical arguments or proof. He also said Teilhard "cheats with words" by using scientific terms in a non-scientific way.

Richard Dawkins

Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins called Medawar's review "devastating." He described The Phenomenon of Man as "the quintessence of bad poetic science."

David Sloan Wilson

In 2019, evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson praised Teilhard's book. He called it "scientifically prophetic in many ways." He sees his own work as an updated version of Teilhard's ideas.

Wolfgang Smith

Wolfgang Smith, a scientist and theologian, wrote a whole book criticizing Teilhard's ideas. He said Teilhard's ideas were not scientific, Catholic, or truly philosophical.

- Evolution: Smith claimed that Teilhard saw evolution as an undeniable truth. Teilhard believed matter becomes spirit and humanity moves towards a super-humanity. This happens through increasing complexity, social connections, and scientific progress.

- Matter and Spirit: Teilhard believed the human spirit came from matter that became more complex. He thought that something non-material could come from something material. He also believed that tiny bits of consciousness existed even at the very beginning of the universe.

- Theology: Smith argued that Teilhard's idea that "God creates evolutively" goes against the Book of Genesis. Genesis says God created man perfectly and completely, and then man fell. This is the opposite of an upward evolution. Smith also said Teilhard believed God evolves with the world.

- New Religion: Smith quoted Teilhard saying he wanted to create "a new religion (call it a better Christianity, if you will)." Teilhard believed that Christians, Marxists, and scientists would eventually unite around the "Christic Omega Point."

Legacy and Influence

Brian Swimme said that Teilhard was one of the first scientists to understand that humans and the universe are connected. He believed the only universe we know is one that created humans.

A very old type of primate fossil was named Teilhardina after him by scientist George Gaylord Simpson.

Influence on Arts and Culture

Teilhard's work continues to inspire artists and writers.

- Characters based on Teilhard appear in novels like Morris West's The Shoes of the Fisherman.

- In Dan Simmons' Hyperion Cantos series, Teilhard de Chardin is a saint in the far future. His work inspires a priest character who later becomes Pope and takes the name Teilhard I.

- Teilhard is a minor character in the play Fake, which is about the Piltdown Man hoax.

- His ideas are the basis for the plot in Julian May's Galactic Milieu Series.

- He is mentioned in Arthur C. Clarke's and Stephen Baxter's The Light of Other Days.

- The title of Flannery O'Connor's short story collection, Everything That Rises Must Converge, refers to Teilhard's work.

- Don DeLillo's novel Point Omega takes its title and some ideas from Teilhard.

- Robert Wright compares his own ideas about evolution to Teilhard's in his book Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny.

Teilhard's work also inspired art.

- French painter Alfred Manessier created L'Offrande de la terre ou Hommage à Teilhard de Chardin.

- American sculptor Frederick Hart created The Divine Milieu: Homage to Teilhard de Chardin.

- A sculpture of the Omega Point with a quote from Teilhard is at the University of Dayton.

- The Spanish painter Salvador Dalí was fascinated by Teilhard's Omega Point theory. His 1959 painting The Ecumenical Council is said to show the "interconnectedness" of the Omega Point.

Music has also been inspired by Teilhard.

- Edmund Rubbra's 1968 Symphony No. 8 is called Hommage à Teilhard de Chardin.

- The Embracing Universe, an oratorio about Teilhard's life and ideas, was performed in 2019.

Several college campuses have honored Teilhard. A building at the University of Manchester is named after him. Residence halls at Gonzaga University and Seattle University are also named after him.

The De Chardin Project, a play celebrating Teilhard's life, ran in Toronto in 2014. A documentary film about his life was planned for 2015.

The American physicist Frank J. Tipler has further developed Teilhard's Omega Point idea in his books. He combines Teilhard's ideas with scientific and mathematical observations.

In 1972, Uruguayan priest Juan Luis Segundo wrote that Teilhard "noticed the profound similarities" between scientific ideas about the universe's evolution.

Fritjof Capra's book The Turning Point: Science, Society, and the Rising Culture positively compares Teilhard to Darwinian evolution.

Death

Teilhard died in New York City on April 10, 1955. He had told friends he hoped to die on Easter Sunday. On Easter Sunday evening, he had a heart attack during a discussion and passed away. He was buried in the Jesuit cemetery in Hyde Park, New York. The property was later sold to the Culinary Institute of America.

See also

In Spanish: Pierre Teilhard de Chardin para niños

In Spanish: Pierre Teilhard de Chardin para niños

- Edouard Le Roy

- Thomas Berry

- Henri Bergson

- Henri Breuil

- Henri de Lubac

- Law of Complexity/Consciousness

- List of science and religion scholars

- List of Jesuit scientists

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

- Noogenesis

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |