Robeson County, North Carolina facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robeson County

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

Robeson County Courthouse and Confederate Monument in Lumberton

|

|||

|

|||

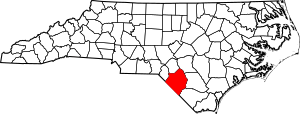

Location within the U.S. state of North Carolina

|

|||

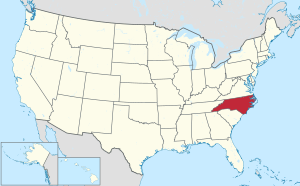

North Carolina's location within the U.S. |

|||

| Country | |||

| State | |||

| Founded | 1787 | ||

| Named for | Thomas Robeson | ||

| Seat | Lumberton | ||

| Largest community | Lumberton | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 949.26 sq mi (2,458.6 km2) | ||

| • Land | 947.30 sq mi (2,453.5 km2) | ||

| • Water | 1.96 sq mi (5.1 km2) 0.21% | ||

| Population

(2020)

|

|||

| • Total | 116,530 | ||

| • Estimate

(2023)

|

117,365 | ||

| • Density | 123.01/sq mi (47.49/km2) | ||

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) | ||

| Congressional district | 7th | ||

Robeson County (pronounced ROB-ih-sun) is a county in the southern part of North Carolina, a state in the United States. It is the largest county in North Carolina based on its land area. The main town and county seat is Lumberton.

The county was created in 1787 from a part of Bladen County. It was named after Thomas Robeson, a colonel who led American forces in the area during the American Revolutionary War. In 2020, about 116,530 people lived here. Robeson County is special because most of its residents belong to minority groups. About 38% are Native American, 22% are white, 22% are black, and 10% are Hispanic. The Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, a state-recognized Native American tribe, has its main office in Pembroke.

Long ago, Native American groups lived in the area that is now Robeson County. By the mid-1700s, a Native community had formed near the Lumber River, which flows through the county. Later, settlers from Scotland, England, and France moved into other parts of the land. For many years, not many people lived here because there wasn't much good land for farming. Timber (wood) and naval stores (products from pine trees like tar and pitch) were very important to the early economy.

In the 1800s, the invention of the cotton gin and a high demand for cotton made Robeson County a major cotton producer. A conflict known as the Lowry War happened during and after the American Civil War. It involved a group of mostly Native American people and local authorities. After this period, a unique system of separating people by race (whites, blacks, and Native Americans) was set up in the county.

In the early 1900s, Robeson County became important for growing tobacco and making textiles (cloth). Many swampy areas were drained, and roads were paved. From the 1950s to the 1970s, there were changes as the county moved away from racial segregation. During this time, farming became more mechanized, and the manufacturing industry grew. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the tobacco and textile industries faced big problems. Now, the county's economy relies more on fossil fuels, chicken farming, and logging. Robeson County still faces challenges in terms of its economy and social well-being.

Contents

History of Robeson County

Scientists have found signs that people have lived in Robeson County for a very long time, since the end of the last Ice Age. These early indigenous peoples (Native Americans) set up camps and villages near the Lumber River. They used the river for water, travel, fishing, and hunting. Tools found here show that Native Americans made stone tools from materials brought from the Carolina Piedmont area. Old pottery found in Robeson County shows that people lived here during the early Archaic and Woodland periods. These findings suggest that local communities traded with other regions.

The area had plenty of water from swamps, streams, and natural springs. Fish were easy to find, and the land had many plants for food. Unique round depressions in the land, called "Carolina bays," are still seen today. Ancient Clovis points (spear tips) found near these bays show that early people used them as campsites thousands of years ago.

After Europeans arrived, Native Americans in the coastal areas traded for European goods like tobacco pipes made of kaolin (a type of clay). These goods were traded by the Spanish, French, and English. The coastal Native Americans then traded these items with groups further inland. European goods have been found in the Robeson County area that are older than the first permanent European settlements along the Lumber River.

Early European Contact

There are not many early written records specifically about the Robeson County region during the time of European colonization. In 1725, maps showed a village of Waccamaw Indians on the Lumber River, a few miles west of where Pembroke is now. In 1773, a report mentioned about 50 families living along "Drowning Creek" (the old name for the Lumber River). These families were described as "mulattos," which usually meant people of African and European descent.

The area that became Robeson County was once part of Bladen County. The English settlers called the river "Drowning Creek." After some big wars between Native Americans and colonists in the early 1700s, some Algonquian Waccamaw families moved from South Carolina in 1718. They might have started a village near Pembroke by 1725. The Iroquoian-speaking Tuscarora tribe moved north and became part of the Iroquois Confederacy.

A famous expert named John R. Swanton from the Smithsonian Institution tried to find out where the group known as "Croatan Indians" came from in the late 1800s. He thought they might be descendants of Siouan-speaking peoples like the Cheraw. Some of his ideas have changed with new discoveries. This group now calls itself the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina and is recognized by the state.

The Lumbee people have a tradition that says they came from Native American ancestors, including people from other tribes like the Tuscarora. They became a distinct group in the early 1800s.

Forming Robeson County

In the mid-1700s, many people from Virginia moved into this frontier area. After the American Revolution, the state used a lottery system to sell land and create the town of Lumberton. The town was officially formed in 1788. John Willis suggested the name "Lumberton" because of the important lumber industry there. This industry, along with naval stores, was a big part of Robeson County's economy throughout the 1800s.

Lumberton was built in an area known as "Drowning Creek." The first courthouse for Robeson County was built on land that belonged to John Willis, the founder of Lumberton. The county's post office opened in 1794. In 1809, the state government changed the name of Drowning Creek to the Lumber River, honoring the main industry.

In the early censuses (1790-1810), some families were listed as white (European American) and others as "free people of color." This term included people of African and Native American descent, as well as those with both African and European backgrounds. Few people in the county owned slaves.

Later research showed that many "free people of color" in North Carolina during these years came from African American families who were free in Virginia during colonial times. These families often had white mothers and African fathers, which gave them free status early on. Some African men who had been slaves were also freed in Virginia in the 1600s. These free families often moved to frontier areas like Robeson County to escape strict racial rules in the older plantation areas.

In the 1800s, other settlers sometimes called mixed-race people "Indian," "Portuguese," or "Arab." This was an attempt to classify them because they looked different from northern Europeans. These people sometimes said they were Indian to avoid the racial segregation linked to people of African descent. Some may have married into the remaining Native American tribes in the area. Many family names found in early Robeson County records belong to these "free people of color" families, including ancestors of today's Lumbee people. Important settlements included Prospect and Red Banks.

Challenges in the 1800s

By the start of the American Civil War, many Native Americans in the South faced difficulties. Their social standing continued to decline. From 1790 onwards, Native Americans in southern states were counted as "free persons of color" in the census, along with free African Americans.

After Nat Turner's rebellion in 1831, North Carolina and other southern states took away rights from "free people of color." Because of fears of slave rebellions, the government stopped them from voting, serving on juries, owning guns, and learning to read and write. In the 1830s, the U.S. government forced many Native American tribes, like the Cherokee, to move west of the Mississippi River. Native Americans who stayed in the Southeast often lived in remote areas to avoid white control.

The Civil War Era

North Carolina left the Union in 1861. A serious yellow fever outbreak in 1862 killed many people in the Cape Fear area. Most white men who could fight had joined the Confederate Army or left the region. The Confederate Army also forced African American slaves to work building forts near Wilmington, North Carolina. This forced labor also affected the "free people of color" in Robeson County.

During the war, the local home guard, which included important white citizens, raided the home of Allen Lowrie, the father of Henry Berry Lowrie. They killed Allen and his son William. Henry Lowrie then swore to get revenge.

Late in the Civil War, General William Tecumseh Sherman and his army moved towards Robeson County. People in the county worried about what would happen after hearing that Sherman's army had burned Columbia, South Carolina. A minister in Lumberton wrote in his diary that Henry Berry Lowrie and his group were causing "much mischief" by destroying white homes. In the final parts of the war, various groups carried out their own conflicts.

For the next seven years, Henry Lowrie led a group of "free people of color," poor whites, and blacks. They fought against the wealthy white leaders. Lowrie became a folk hero to many poorer people.

The 1900s and Beyond

For much of the 1900s, Robeson County was a place where the Ku Klux Klan (a white supremacist group) was active. However, on January 18, 1958, armed Lumbee people bravely chased away about 50 Klansmen and their supporters in the town of Maxton. This event is known as the Battle of Hayes Pond.

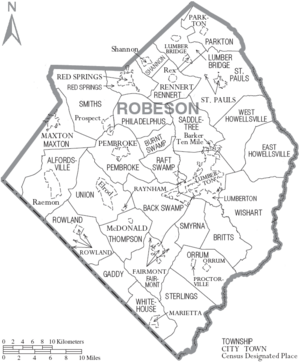

Geography and Nature

Robeson County covers about 949 square miles. Most of this is land (947 square miles), and a small part is water (1.96 square miles). It is the largest county in North Carolina by land area. Because it's so big, people sometimes jokingly called it the "State of Robeson." It shares borders with several counties in North Carolina and South Carolina.

Robeson County is in the Coastal Plain region of the state. It is also part of the Sandhills region, which has sandy and fertile soil. The county has 11 main types of soil, mostly sandy loams. It has a mild climate and rarely gets snow. The county has many pocosins (a type of wetland), bald cypress forests, Carolina bays, and about 50 swamps. These swamps flow into the Lumber River, which runs from the northwest to the southeast corner of the county. Parts of the Lumber River State Park are in Robeson County, as is the Warwick Mill Bay State Natural Area.

Most of Robeson County is in the Lumber River basin. The river and its banks are home to many plants and animals. Mammals like deer, raccoons, beavers, and otters live here. Wild turkeys and different kinds of ducks are also found. The river has many fish, including catfish, perch, and bass. Reptiles include copperhead snakes and cottonmouths (water snakes). Robeson County is also one of the westernmost places in North Carolina where you can find American alligators. Plants along the river include bald cypress, gum, poplar, and juniper trees. You can also find ferns, Spanish moss, and even Venus flytraps.

People and Population

Who Lives in Robeson County?

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (not Hispanic) | 29,159 | 25.02% |

| Black or African American (not Hispanic) | 26,218 | 22.5% |

| Native American | 43,536 | 37.36% |

| Asian | 897 | 0.77% |

| Pacific Islander | 63 | 0.05% |

| Other/Mixed | 4,900 | 4.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 11,757 | 10.09% |

In 2020, there were 116,530 people living in Robeson County. There were 46,272 households and 30,034 families.

Changes in Population

| Historical population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Between 2010 and 2020, Robeson County's population went down by about 17,638 people. This was the biggest drop in any North Carolina county. During this time, the number of white residents decreased the most. However, the number of Hispanic residents and people who identify as two or more races increased. The number of people under 18 years old dropped by 22%. But between 2020 and 2023, the county's population started to grow again slightly.

Economy and Jobs

For most of the 1900s, Robeson County's economy depended on making textiles and growing tobacco. In 1960, farming was the biggest employer. The county made the second-highest amount of money from agriculture in the Southern United States. However, the average income for people living there was still low. By 1970, manufacturing (making goods in factories) had become more important than farming. The completion of Interstate 95 helped factories grow even faster.

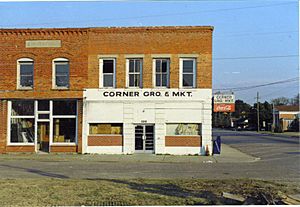

By 1990, fewer than 2,300 people in Robeson County worked in farming. Manufacturing provided jobs for one-third of the county's workers. But in the 1990s and early 2000s, the tobacco and manufacturing industries quickly declined. This was partly due to national free trade agreements. For example, the North American Free Trade Agreement led to 32 factories closing and over 6,000 jobs being lost between 1995 and 2005. From 1997 to 2007, the county also lost a lot of farmland.

Today, tobacco is still grown in the county, along with corn, soybeans, peanuts, and cotton. Some landowners grow pine trees and sell them for timber. Chicken farming has also grown a lot since the 1990s. In recent years, businesses have grown along the Interstate 95 highway. Chicken and pork processing plants, and the pellet fuel industry, have replaced many of the old textile jobs. Some people worry that these industries cause a lot of pollution.

The biggest job sectors in Robeson County are healthcare, manufacturing, retail, education, and food service. In 2022, the average household income was $38,610. As of 2023, 28% of local residents live in poverty. This makes Robeson one of the poorest counties in North Carolina. In 2024, the state government ranked Robeson as one of the most economically struggling counties.

Transportation and Travel

Robeson County has two major highways: Interstate 95, which goes north and south, and Interstate 74 (which is still being built), going east and west. These two highways meet southwest of Lumberton. Other important roads include U.S. Route 74, US 301, and US 501, along with many North Carolina state highways.

The county government provides a public bus service called the South East Area Transit System. For air travel, there is the Lumberton Municipal Airport in Lumberton. The Laurinburg–Maxton Airport, which is near the border with Scotland County, serves both Laurinburg and Maxton. Railroads in Robeson County are run by CSX Transportation. The longest straight stretch of railroad track in the United States, almost 79 miles long, goes through Robeson County.

Education and Learning

The Public Schools of Robeson County (PSRC) manages all the public schools in the county. In 2022, the school system had 36 schools and served about 23,000 students. The state has classified the PSRC as a "low-performing" school district.

The county also has two colleges: the University of North Carolina at Pembroke and Robeson Community College. The PSRC also supports the Robeson Planetarium, where you can learn about space. The county government runs seven libraries. There is also a county history museum in Lumberton. In 2022, about 16.4% of adults in the county had a bachelor's degree or higher education.

Healthcare Services

Robeson County has one hospital, UNC Health Southeastern, located in Lumberton. The Robeson Health Care Corporation also offers medical care through various clinics. In 2022, a study found that Robeson County had the worst health outcomes among all North Carolina counties. This means that 32% of adults said they were in poor or fair health. The average life expectancy (how long people are expected to live) is 72 years, which is six years lower than the state average. Also, 19% of people under 65 do not have health insurance.

Culture and Traditions

Locals pronounce Robeson as "RAH-bih-sun" or "ROB-uh-son." People from outside the area sometimes say "ROW-bih-sun." Because the county has three main ethnic groups (whites, blacks, and Native Americans), these groups often have their own social and cultural ways. People from each group often speak with different accents.

A popular dish among the Lumbee people in the county is the collard sandwich. It's made with fried cornbread, collard greens, and fatback (a type of pork fat). Many small communities in the county are very close-knit and don't have much contact with people from outside the county. Most towns have their own yearly festivals. The Lumbee Homecoming is a festival for members of the Lumbee tribe, held every year in late June and early July. It brings thousands of Lumbee people and tourists to the county.

Fishing and hunting have always been popular activities in the county, both for food and for fun. The "Carolina boat," a type of small boat made of marine plywood, was first designed in Robeson County. Many people in the county are religious, and religion is an important part of local life. Several buildings and places in the area are listed on the National Register of Historic Places because of their historical importance.

Communities in Robeson County

City

Towns

- Fairmont

- Lumber Bridge

- Marietta

- Maxton

- McDonald

- Orrum

- Parkton

- Pembroke

- Proctorville

- Raynham

- Red Springs

- Rennert

- Rowland

- St. Pauls

Townships

- Alfordsville

- Back Swamp

- Barnesville

- Britts

- Burnt Swamp

- East Howellsville

- Gaddy

- Parkton

- Philadelphus

- Raft Swamp

- Rennert

- Saddletree

- Shannon

- Smiths

- Smyrna

- Sterlings

- Thompson

- Union

- West Howellsville

- Whitehouse

- Wishart

Census-designated places

Unincorporated communities

- Bloomington

- Five Forks

- Red Banks

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Condado de Robeson para niños

In Spanish: Condado de Robeson para niños