Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta facts for kids

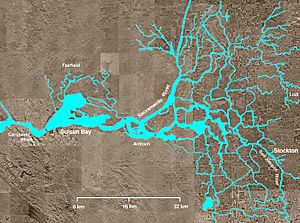

The Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, also known as the California Delta, is a huge area of waterways and land in Northern California. It's where the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers meet. This special place is just east of Suisun Bay, where the rivers flow out to the ocean.

The Delta is important for many reasons. It's a protected area and was named a National Heritage Area in 2019. The city of Stockton is located on the San Joaquin River at the Delta's eastern edge. The Delta covers about 1,100 square miles (2,850 square kilometers) of land and water. Around 500,000 people live here.

This Delta formed about 10,000 years ago, after the last Ice Age. As sea levels rose, river sediment built up behind the Carquinez Strait. This narrow opening to the San Francisco Bay slowed the water, causing the sediment to settle and create large islands. In its natural state, the Delta was a big freshwater marsh. It had many shallow channels and small islands made of peat and tule plants.

Since the mid-1800s, much of the Delta has been turned into farmland. Over time, the land has sunk in many areas. This is because the peat soil broke down when exposed to air. Today, much of the Delta is below sea level, protected by walls called levees. This is why it's sometimes called "California's Holland". The Delta also provides a lot of water for farms and cities in Central California and Southern California. Large pumps at the Delta's southern end send this water to where it's needed.

Contents

Exploring the Delta's Geography

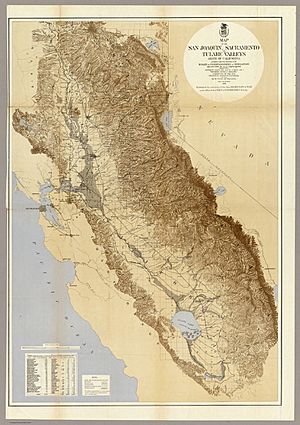

The Delta has about 57 main reclaimed islands and tracts, but nearly 200 named or unnamed islands in total. These islands are surrounded by about 1,100 miles (1,770 km) of levees. These levees protect about 700 miles (1,126 km) of waterways. The Delta is mostly located in Contra Costa, Sacramento, San Joaquin, Solano, and Yolo Counties.

The Delta covers about 1,153 square miles (2,986 square kilometers). Almost 73 percent of this area is used for farming. About 100 square miles (259 square kilometers) are city areas, and 117 square miles (303 square kilometers) are undeveloped land. The rivers, streams, and channels cover about 95 square miles (246 square kilometers) of surface water. This amount changes with the seasons and tides.

The main rivers flowing into the Delta are the Sacramento River from the north and the San Joaquin River from the southeast. The Calaveras and Mokelumne Rivers also flow in from the east. The Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers meet at the western end of the Delta near Pittsburg. They are also connected upstream by the Georgiana Slough. This shortcut was used by steamboats in the 1800s between Sacramento and Stockton. These rivers carry about half of all California's runoff water through the Delta each year.

Cities near the Delta include Lodi and Stockton to the east, Tracy and Manteca to the south, and Brentwood, Pittsburg, and Antioch to the west. The state capital, Sacramento, is just north of the Delta.

The Sacramento Deep Water Ship Channel connects the Delta to the Port of Sacramento. The Stockton Ship Channel is a deepened part of the San Joaquin River. It cuts through the Delta from the Port of Stockton to where the San Joaquin meets the Sacramento River.

How the Delta Formed Naturally

Long ago, the Central Valley was a large inland sea. About 560,000 years ago, water broke through the mountains, creating the Carquinez Strait and San Francisco Bay. This narrow opening caused rivers to slow down and drop their sediment, which helped form the Delta.

The Delta as we know it today began to form about 10,000 years ago. At the end of the last Ice Age, global sea levels were much lower. The Delta area was a river valley where the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers flowed to the Pacific Ocean. When sea levels rose, ocean water flowed back into the Central Valley through the Carquinez Strait. This slowed the rivers and made them drop more sediment.

About 8,000 years ago, the sea level stopped rising so quickly. This allowed wetland plants to grow in the Delta, trapping more sediment. As these plants grew and decayed, they formed thick layers of peat. This peat makes up the Delta islands. The Delta reached its stable form, similar to how it was in the mid-1800s, about 2,000–3,000 years ago.

Before humans developed the Delta, most islands were shaped like a saucer. They had low natural levees (banks) around a marshy middle. This middle part would flood often with the seasons and tides. About 60 percent of the Delta would flood for a few hours each day at high tide. During very high tides or river floods, the entire Delta could be underwater.

A Look at the Delta's History

Humans have lived in the Delta for up to 4,300 years. Before Europeans arrived, about 3,000 to 15,000 Native Americans lived here, mainly the Miwok and Maidu people. They lived in villages on the higher eastern edge of the Delta, where there was less flooding. They used the abundant reeds, or tules, to build houses, boats, and clothes. Their food included tule roots, acorns, wild fruits, and fish.

Europeans first saw the Delta in 1772. Spanish explorer Pedro Fages and missionary Juan Crespí viewed it from Mount Diablo. For many years, the Spanish did not use the Delta much. However, military trips were made into the Delta from 1813 to 1845. This was because of conflicts between Native Americans and the Spanish and later Mexicans. John Sutter, a European settler, started the first major settlement just north of the Delta near present-day Sacramento.

Many Native Americans were forced to work for the Spanish. Some fled deep into the Delta to escape. However, diseases still affected them. A malaria outbreak in 1833 greatly reduced the native populations. This was likely made worse by the marshy area, which had many mosquitoes.

People realized how valuable the Delta's farmland was during the California Gold Rush. Farmers grew fruits on Delta islands to sell to miners. It was cheaper to irrigate here than in other parts of California because the land was flat and had fresh water all year. The Delta remained one of California's richest farming areas until the 1940s. Today, it is still one of the state's most productive farming regions.

In 1850, a law called the Swamp Land Act of 1850 allowed wetlands to be given to private owners if they were drained. In California, over 2 million acres of wetlands were given away, with 500,000 acres in the Delta. Farmers built levees to protect their land. Chinese laborers did much of this hard work from the 1850s to the 1870s. Early levees were made of peat and easily damaged by wind and water. Major floods in 1862, 1878, and 1881 forced landowners to build stronger levees.

By 1900, almost half of the Delta's land area, about 235,000 acres, had been reclaimed. Most of the Delta's farmable land was reclaimed by the 1920s.

Delta's Economy and Uses

Farming in the Delta

The Delta produces crops worth about $650 million each year. This makes it one of the most productive farming areas in the United States. Farming also brings in over $2 billion to the local economy. Major crops include corn, grain, hay, sugar beets, tomatoes, and asparagus. Some fruits and livestock are also raised here. Farmers use a special way to water their crops. They pipe water into small ditches, which spreads water over large areas and raises the water level in the soil.

Transportation Routes

The Delta's waterways are important for moving farm products. The ports of Sacramento and Stockton are California's most important inland ports. The San Joaquin River and the lower Sacramento River are regularly deepened. This allows large cargo ships to pass through. The Delta is also home to the port of Benicia, which handles cars and other goods. Oil is shipped to refineries in Benicia and Martinez. The Port Chicago Marine Ocean Terminal is a U.S. Navy facility nearby.

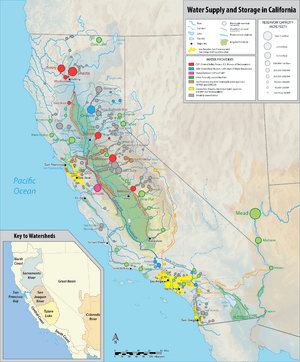

California's Water Supply

The Delta is like the heart of California's water system. About half of all the river water in the state flows through this area. From here, water is sent to other parts of the San Joaquin Valley, Southern California, and parts of the Bay Area. This water supplies about 1.13 million acres of farmland and 23 million people. The Delta provides about 7 million acre-feet of water per year. Most of this water goes to the San Joaquin Valley and Southern California.

Salty water naturally flows into the Delta from the ocean. However, this became a bigger problem after farming reduced the amount of fresh water flowing in. Several droughts between 1910 and 1940 caused a lot of salt to enter the Delta. This problem led to the building of dams on Central Valley rivers. These dams helped increase freshwater flows during dry seasons. This became the federal Central Valley Project (CVP), California's first major statewide water system.

Today, the California Aqueduct and the Delta-Mendota Canal draw water from the southern Delta. The California Aqueduct sends water to the Los Angeles Basin and central California. The Delta-Mendota Canal provides water for farms in the San Joaquin Valley. The Contra Costa Canal and North Bay Aqueduct also take Delta water to the San Francisco Bay Area. Locally, the Delta provides water for cities and towns in five counties and for over 1,800 farms.

Fun and Recreation

The Delta is a popular place for fun activities. People enjoy sailing, waterskiing, houseboating, fishing, and hunting. The Delta has over 100 marinas and 25 yacht clubs. In 2010, more than seven million boating trips happened on the Delta.

Several state and regional parks are in the Delta. These include historical sites like Delta Meadows and Locke Boarding House and the Old Sacramento State Historic Park. The Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial teaches visitors about a significant event in U.S. history that happened there during World War II.

Brannan Island State Recreation Area offers boat launches and places for fishing, windsurfing, and waterskiing. It also has campsites, picnic areas, and trails to explore the marshes and islands.

Franks Tract State Recreation Area was once a farming island that flooded in 1936 and 1938. The levees were never fixed, and the island became open water. It is now a state park, accessible only by water. People use it for fishing, waterfowl hunting, and boating.

The Pacific Flyway, a route for birds migrating north and south, crosses the Delta. This offers great opportunities for birdwatching and hunting. There are over 150 private duck clubs in the area, including the northern Suisun Marsh.

Impact of Levees and Water Diversion

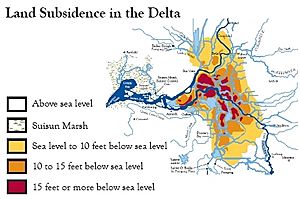

The levee system allowed farmers to drain and use almost 500,000 acres of the Delta. This area was once a tidal marsh. Once the rivers were kept in their beds, the peat soil of the marsh was exposed to air. When the peat soil broke down, it released carbon dioxide. This caused the land to sink greatly, up to 25 feet since the late 1800s.

Today, most of the Delta is below sea level. Much of the western and central Delta is at least 15 feet (4.6 meters) below sea level. The California Department of Water Resources has tried reflooding some areas. This helps restore wetlands, store carbon, and rebuild soil levels. Flooding the land also helps reduce sinking and restore the wetlands.

Land sinking has put the Delta's levees at risk. Sometimes, a levee breaks, causing flooding.

Land sinking also allows salty water to enter the Delta. This problem is made worse because up to 25% of the fresh water flowing into the Delta is diverted away. The reduced amount of fresh water has greatly affected the Delta's environment. Large dams in the Delta's watershed hold back spring runoff. This makes the Delta more likely to have salty water between February and June. However, dams also help increase freshwater flows during dry summers and autumns, which reduces the risk of salt intrusion then.

Pumps at the southern end of the Delta also cause problems. These powerful pumps, which supply water for the Central Valley Project and State Water Project, make water in the Delta flow from north to south. Normally, it would flow from east to west. This has caused environmental issues. For example, it disrupts fish migration and causes salt to build up in the eastern Delta.

Levee Breaks and Risks

Since 1900, there have been over 160 levee breaks in the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta. This includes times when the same levee broke more than once. Levee breaks can happen when water flows over the top or when the structure itself fails. One recent example was in June 2004. A levee break caused over 150,000 acre-feet of water to flood all of Jones Tract.

However, major improvements have been made to the Delta levee system since 1982. This has greatly reduced the number of failures. There has only been one major failure in 30 years. A study found that the Delta levee system is now quite strong. But it should be improved even more to prevent failures during extreme floods and earthquakes. This is important because valuable things like water pipes and roads pass through the Delta.

A 2019 article said there is a 62 percent chance of a major levee failure in the next two decades. This means 20 islands could flood at once if land sinking is not fixed.

If many levees on the Delta's 57 islands broke at the same time, perhaps after an earthquake, salty water from the San Francisco Bay could flow in. This would threaten the water supply for the Central Valley. This water is used for its $17 billion farming economy and for drinking water for about 25 million people.

Delta's Ecosystem

The Delta is home to about 500 types of plants and animals. It is one of the largest estuaries in western North America. Before farming, the Delta islands were covered with tule, bulrush, and other reeds. These plants grew well in the marshy areas that flooded often. Over thousands of years, these plants grew and decayed, forming peat soil up to 50 feet (15 meters) deep. This is why Delta soils are so fertile.

Sediment deposits formed natural levees around the islands. Larger trees, mostly willows, grew here. These formed large forests along the rivers. More woodlands grew on the edges of the Delta, with trees like valley oak, box elder, and Oregon ash. Farther from the water, the land was grassland.

The water hyacinth has become a very harmful plant in the Delta. It can spread quickly, covering up to 6,500 square feet (604 square meters) of water in one growing season. It is a big challenge for farmers to remove. The plants spread by budding and by dropping seeds. These seeds can stay alive in the mud for years. Water hyacinth can form a mat up to 6 feet (1.8 meters) thick. This blocks sunlight and makes the water acidic when it decays.

The Delta used to have large groups of deer and tule elk. Their trails were so big that early Spanish explorers thought cattle lived there. Many California grizzly bears also lived in the Delta. The Delta's wetlands supported huge numbers of birds. Even today, half of California's migrating waterfowl pass through the Delta. A survey in 2012 found 48.6 million ducks in spring, the highest number since counts began in 1955. Large mammals in the Delta have not done as well. Most of their homes were turned into farms. Grizzlies were hunted until they disappeared. The flood of 1878 wiped out the last elk herds in the Delta.

The Delta is home to about 22 types of fish. These include several Pacific salmon species, striped bass, steelhead trout, and sturgeon. About two-thirds of California's salmon pass through the Delta to lay their eggs upstream. The small Delta smelt is an important fish that shows how healthy the Delta's ecosystem is. Delta fish populations have greatly decreased because marshland was drained and fresh water was diverted. In 2004, the Delta smelt was almost extinct. Protecting the Delta smelt has been a big environmental debate in California. Measures to protect it often reduce the water available for federal water projects.

The California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment advises people not to eat fish caught in the Central and South parts of the Delta. This is because of high levels of mercury and PCBs. There is also a "DO NOT EAT" warning for any fish or shellfish from the Port of Stockton. There is a separate advisory for the Northern part of the Delta.

Nutria were found in Merced County, near the Delta, in 2017. State officials are worried these animals will damage the water systems that send water to farms and cities.

The Delta has had many blooms of cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) more often in the last 20 years. These bacteria can produce toxins that can harm humans and animals if they come into contact with them. One common type, Microcystis aeruginosa, produces toxins that can cause liver cancer. These blooms have affected the Delta's food web. They reduce the number of different types of aquatic microbes and decrease the amount of zooplankton. There is also concern that these toxins can build up in the food web. Toxins were found in clams at much higher levels than in the water around them.

The increase in cyanobacteria blooms in the Delta is due to several factors. The most important is lower streamflow. Researchers found that blooms appeared when the water reached 19°C (66°F). This was made worse by less rain, reduced streamflow, and more nutrients in the water. Climate change, with less rain and higher temperatures, could further increase these blooms. High nutrient levels in the Delta also play a big part. Microcystis grows well with human-made nitrogen, allowing it to out-compete other plants and dominate the lower food levels.

The increased presence of Microcystis aeruginosa blooms in the Delta is a constant threat to species at many levels of the food web. Lower levels are affected by reduced diversity and numbers. When conditions are right, Microcystis can take over. Also, when toxins are present, animals in the food web are at risk because the toxins can build up in their bodies. Fish active during blooms can have high toxin levels, which can cause health problems. Since toxins can build up in fish, it also poses a risk for humans who eat them.

Protecting the Delta

After many efforts to fix problems caused by water pumping restrictions, several solutions have been suggested for the Delta. One idea is to keep the Delta as it is now. Another is to restore parts of the Delta to its natural state. This would also include building a new Peripheral Canal to keep the water supply flowing.

The Contra Costa County Public Works Department is working to protect drinking water quality, prevent pollution, and improve the Delta's environment.

In April 2009, the Sacramento River in the Delta was named the nation's most endangered waterway system by the group American Rivers. This was due to water shortages, fewer fish, and old levees, among other issues.

Since the 1940s, different groups have wanted to build a Peripheral Canal. This canal would send water from the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers directly to the large aqueducts that take water from the southern Delta. Right now, fresh water has to flow through many channels before reaching the Clifton Court Forebay. From there, water is pumped into the California Aqueduct and Delta-Mendota Canal. Also, many Delta smelt and other endangered species are killed by these pumping plants.

The current plan, called the Bay Delta Conservation Plan, involves building twin tunnels under the Delta. This plan is supported by Governor Jerry Brown. However, some people are against the Peripheral Canal idea. They worry it would further reduce the amount of fresh water flowing through the Delta. Farmers in the Delta are especially against it, as it would mean less water for their crops.

All solutions aim to create a Delta that supports a healthy environment. At the same time, it needs to keep supplying fresh water to the Central Valley Project, the State Water Project, and the Bay Area.

The Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta National Heritage Area was created on March 12, 2019. It is the first such area in California. The Delta Protection Commission manages this heritage area.

Images for kids

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |