Technology during World War I facts for kids

Technology during World War I (1914–1918) showed how much the world was changing. Factories could now make huge amounts of weapons and tools for war. This idea of using mass-production for military gear had started even before the war, like during the American Civil War (1861–1865). Many smaller fights also helped soldiers and leaders test out new weapons.

Weapons in World War I included older types that had been made better, plus brand-new ones using exciting technology. Soldiers also used many improvised weapons, especially in the trenches. Important new tools included better machine guns, grenades, and big artillery guns. Completely new weapons appeared too, like submarines, poison gas, warplanes, and tanks.

At the start of the war, armies tried to fight with 19th-century plans but used 20th-century weapons. This led to battles with huge numbers of deaths on both sides. On land, fighting quickly turned into trench warfare, which surprised everyone. Only in the last year of the war did armies figure out how to use new technologies and change their tactics to fit the modern battlefield. They started using smaller groups of soldiers, along with armored cars, early submachine guns, and automatic rifles that one soldier could carry.

Contents

- Life in the Trenches: New Ways to Fight

- Artillery: Big Guns and New Tactics

- Poison Gas: A Frightening New Weapon

- Command and Control: Talking Across the Battlefield

- Railways: Moving Armies and Supplies

- War of Attrition: Wearing Down the Enemy

- Air Warfare: Taking to the Skies

- Mobility: Moving Across the Land

- At Sea: New Naval Power

- Small Arms: Weapons for Soldiers

- Flamethrowers: Fire in the Trenches

- See also

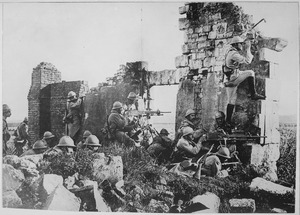

Life in the Trenches: New Ways to Fight

The new ways of making metal and chemicals created powerful weapons. These weapons made it much easier to defend a position than to attack it. It became very hard to cross enemy lines because of infantry rifles, powerful artillery with special recoil systems, barbed wire, zigzag trenches, and machine guns.

The hand grenade, which had been around for a long time in simple forms, quickly got better. It became a key tool for attacking trenches. Also, the invention of high explosive shells made artillery much deadlier than before.

Trench warfare also led to the concrete pillbox. This was a small, strong building used to fire machine guns. Pillboxes were placed across the battlefield so their guns could cover each other, making it very hard for enemies to get through.

Because attacking enemies in trenches was so difficult, tunnel warfare became a big part of the war. Soldiers would dig tunnels under enemy positions, plant huge amounts of explosives, and blow them up. This would clear the way for an attack above ground. Special listening devices were vital to hear enemy digging and stop their tunnels. British "sappers" (engineers) were especially good at this, thanks to their digging skills and advanced listening tools.

The constant threat from snipers in the trenches meant soldiers needed safe ways to shoot and watch. They often used steel plates with a "keyhole" opening. This opening had a spinning part that could close it when not in use.

Soldier's Clothes and Helmets

Before the war, British and German armies had already stopped wearing bright uniforms like red or blue. They switched to less noticeable colors like khaki (British) or field gray (German). French leaders wanted to do the same, but their army went to war in traditional red trousers. They only started getting new "horizon blue" uniforms in 1915.

A type of raincoat for British officers, which existed before the war, became famous as the trench coat.

At the start of the war, most soldiers wore cloth caps or leather helmets. But soon, armies quickly developed new steel helmets. The designs of these helmets became symbols of their countries.

Hiding in Trees

Watching the enemy in trench warfare was hard. This led to inventions like the camouflage tree. This was a fake tree that soldiers could hide in to secretly watch the enemy.

Artillery: Big Guns and New Tactics

In the 1800s, Britain and France made artillery that was good for moving battles. These guns worked well in colonial wars and for Germany in the Franco-Prussian War. But trench warfare was more like a siege, needing very heavy guns. Germany had already thought about this and had more heavy artillery ready. Factories quickly started making more large guns and fewer small, mobile ones. Germany even built the Paris guns, which were huge and could shoot incredibly far. However, these guns wore out quickly and had to be sent back to the factory often. They mostly scared people in cities rather than causing much damage.

At the start of the war, artillery was often placed at the front lines to shoot directly at enemy soldiers. During the war, many improvements were made:

- For the first time, guns could shoot at enemy artillery without seeing them (indirect counter-battery fire).

- Forward observers were used to guide artillery from a distance. Complex communication and firing plans were created.

- New methods like Artillery sound ranging and flash spotting helped find and destroy enemy guns.

- Things like weather, air temperature, and how much a gun barrel had worn out could now be measured. This made indirect fire much more accurate.

- The first "box barrage" happened in 1915. This was when shells created a three or four-sided wall of explosions to stop enemy soldiers from moving.

- The "creeping barrage" was perfected. This was a moving wall of shell fire that advanced just ahead of attacking infantry.

- The No. 106 fuze was made to explode when it hit barbed wire or the ground. This stopped shells from getting stuck in mud and was also good against soldiers.

- The first anti-aircraft guns were invented to shoot down enemy planes.

When the war began, armies thought each gun would need a few hundred shells, and armories would have about a thousand ready. This was completely wrong! It became common for a gun to fire a hundred or more shells every day for weeks or months. To fix the "Shell Crisis of 1915," factories quickly changed to make more ammunition. Railways to the front were expanded, but getting supplies the "last mile" was still a problem. Horses in World War I were the main solution, and many died, which hurt the Central Powers later in the war. New trench railways helped in many places. Early motor trucks were not very good yet, lacking modern tires and suspension.

Most of the deaths during the war were caused by artillery fire.

Poison Gas: A Frightening New Weapon

Chemical weapons were used in a big way for the first time in this war. These included phosgene, tear gas, and mustard gas.

At the start of the war, Germany had the best chemical industry in the world. They made over 80% of the world's dyes and chemicals. Even though the use of poison gas was banned by international agreements, Germany hoped it would be a decisive weapon to break the trench warfare stalemate.

Chlorine gas was first used in April 1915 at the Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium. The gas looked like a simple smoke screen, meant to hide attacking soldiers. Allied troops were ordered to the front trenches to stop the expected attack. But the gas had a terrible effect, killing many defenders. Sometimes, when the wind changed, it blew the gas back onto the attackers.

Because the wind was unreliable, another way to deliver the gas was needed. It started being fired in artillery shells. Later, mustard gas, phosgene, and other gases were used. Britain and France soon started using their own gas weapons too. The first ways to protect against gas were simple, like rags soaked in water or urine. Later, good gas masks were developed, which greatly reduced how effective gas was as a weapon. Even though gas sometimes gave a short-term advantage and caused over 1,000,000 injuries, it did not change the overall outcome of the war much.

Chemical weapons were easy to get and cheap. Gas was especially effective against soldiers in trenches and bunkers, where other weapons couldn't reach them as well. Most chemical weapons attacked a person's breathing system. The idea of choking easily caused fear in soldiers, and this terror affected them mentally. Because there was such a great fear of chemical weapons, soldiers sometimes panicked and thought common cold symptoms were from poison gas.

Command and Control: Talking Across the Battlefield

The invention of radio telegraphy was a big step for communication in World War I. The radio stations used then were "spark-gap transmitters." For example, the news that World War I had started was sent to German South West Africa on August 2, 1914, using radio from Germany, through relay stations in Togo, to the station in Windhoek.

In the early days of the war, generals tried to control battles from headquarters many miles from the front. Messages were carried by runners or on motorcycles. Soon, everyone realized they needed faster ways to communicate.

Radio sets were too heavy to carry into battle. Field telephone lines laid down were often quickly broken. Both radios and telephones could be listened to by the enemy, and secret codes were not very good. So, runners, flashing lights, and mirrors were often used instead. Dogs were also used, but not often, because soldiers tended to adopt them as pets, and men would volunteer to run messages instead of letting the dog go. There were also aircraft (called "contact patrols") that carried messages between headquarters and front lines, sometimes dropping them without landing. However, radio technology kept getting better during the war, and radio telephones were perfected. They were most useful for pilots spotting artillery targets from the air.

The new long-range artillery developed just before the war now had to shoot at targets it couldn't see. A common tactic was to heavily shell enemy front lines, then stop to let infantry attack, hoping the enemy line was broken. This rarely worked. The "lifting barrage" and then the "creeping barrage" were developed. These kept artillery fire landing right in front of the infantry "as it advanced." Since communication was hard, the danger was that the barrage would move too fast (losing protection) or too slowly (holding up the attack).

There were also ways to fight back against these artillery tactics. By aiming a counter-barrage right behind an enemy's creeping barrage, soldiers could target the infantry following it. Microphones (Sound ranging) were used to figure out where enemy guns were and then shoot back at them (counter-battery fire). The flashes from enemy guns firing could also be spotted and used to target their artillery.

Railways: Moving Armies and Supplies

Railways were incredibly important in this war. For example, the German battle plan was known by the Allies partly because of the huge railway yards near the Belgian border. These yards had no other purpose than to bring the German army to its starting point. The German plan for moving their army was basically a giant railway schedule.

Men and supplies could get to the front faster than ever by train. But trains were vulnerable right at the front lines. So, armies could only advance as fast as they could build or rebuild railways. For instance, the British advance across Sinai depended on building railways. Motorized transport was only widely used in the last two years of World War I. After the railway ended, troops walked the "last mile," and guns and supplies were pulled by horses and trench railways. Railways were not as flexible as motor transport, and this lack of flexibility affected how the war was fought.

War of Attrition: Wearing Down the Enemy

The countries fighting in the war used their full industrial power to make weapons and ammunition, especially artillery shells. Women at home played a key role by working in munitions factories. This complete use of a nation's resources, called "total war," meant that not only armies but also the economies of the warring nations were competing.

For a time, in 1914–1915, some hoped the war could be won by simply running out the enemy's supplies. They thought the enemy would use up all their artillery shells in pointless attacks. But both sides quickly made more and more supplies, so this hope faded. In Britain, the Shell Crisis of 1915 even caused the government to change. It led to the building of HM Factory, Gretna, a huge ammunition factory.

The "war of attrition" then focused on another resource: human lives. In the Battle of Verdun, for example, the German Chief of Staff, Erich Von Falkenhayn, hoped to "bleed France white" by repeatedly attacking this French city.

In the end, the war finished because of a mix of things: running out of men and supplies, advances on the battlefield, many American troops arriving, and a breakdown of morale and production on the German home front. This last part was due to an effective naval blockade of Germany's seaports.

Air Warfare: Taking to the Skies

Aviation in World War I started with simple planes used in basic ways. But technology quickly improved. This led to planes attacking ground targets, tactical bombing, and famous, deadly "dogfights" between planes. These planes had machine guns that fired forward, thanks to a special device that let them shoot through the propeller starting in July 1915. However, planes had a bigger impact on the war in less exciting roles, like gathering information, patrolling the sea, and especially helping artillery aim. Antiaircraft warfare also began in this war.

Like most technologies, aircraft and how they were used got much better during World War I. When the war on the Western Front settled into trench warfare, aerial reconnaissance (scouting from the air) made it harder for armies to surprise hidden defenders.

Manned observation balloons floated high above the trenches. They were used as stationary observation posts, reporting enemy troop positions and guiding artillery fire. Balloons usually had two crew members, each with a parachute. If an enemy plane attacked the flammable balloon, the crew would jump to safety. At the time, parachutes were too heavy for pilots in planes. Smaller versions were not made until the end of the war. (The British also worried that parachutes might make pilots less brave.) Because they were so valuable for observation, balloons were important targets for enemy planes. To protect them, balloons were heavily guarded by many anti-aircraft guns and friendly planes.

Early air spotters were unarmed, but they soon started shooting at each other with handheld guns. This led to a race to build better planes with machine guns. A key invention was the interrupter gear. This Dutch invention allowed a machine gun to be mounted behind the propeller, so the pilot could shoot straight ahead, along the plane's flight path.

As the fighting on the ground became a stalemate, with neither side able to advance much without huge losses, planes became very important for gathering information about enemy positions. They also bombed enemy supplies behind the trench lines, like later attack aircraft. Large planes with a pilot and an observer were used to scout enemy positions and bomb their supply bases. These big, slow planes were easy targets for enemy fighter planes. This led to fighter escorts and amazing aerial dogfights.

German strategic bombing during World War I hit cities like Warsaw, Paris, and London. Germany led the world in Zeppelins (large airships). They used these airships for occasional bombing raids on military targets and British cities, but they didn't cause much damage. Later in the war, Germany introduced long-range strategic bombers. Again, the damage was minor, but these bombers forced the British air forces to keep fighter squadrons in England to defend against air attacks. This meant fewer planes, equipment, and people were available for the British army on the Western Front.

The Allies made much smaller efforts to bomb the Central Powers.

Mobility: Moving Across the Land

At the start of the war, armored cars with machine guns were used in combat units. There were also soldiers on bicycles and machine guns on motorcycle sidecars. While they couldn't attack strong enemy positions, they gave mobile fire support to infantry. They also did scouting, reconnaissance (finding out about the enemy), and other jobs similar to cavalry. Once trench warfare took over the main battle lines, there were fewer chances for such vehicles. However, they continued to be used in the more open areas like Russia and the Middle East.

Between late 1914 and early 1918, the Western Front barely moved. When the Russian Empire surrendered after the October Revolution in 1917, Germany could move many troops to the Western Front. With new stormtrooper infantry trained in infiltration tactics (finding weak points and getting behind enemy lines), they launched a series of attacks in the spring of 1918. In the biggest of these, Operation Michael, General Oskar von Hutier pushed forward 60 kilometers. This gained in a few weeks what France and Britain had spent years trying to achieve. Although these attacks were successful at first, they stopped because the German forces ran out of supplies, artillery, and fresh troops, which were pulled by horses. This left the German forces weak and tired.

In the Battle of Amiens in August 1918, the Triple Entente (Allied) forces started a counterattack called the "Hundred Days Offensive." Australian and Canadian divisions led the attack and managed to advance 13 kilometers on the first day alone. These battles marked the end of trench warfare on the Western Front and a return to mobile warfare.

The mobile personnel shield was a less successful attempt to bring back mobility.

After the war, the defeated Germans tried to combine their 1918 infantry tactics with vehicles. This eventually led to blitzkrieg, or 'lightning warfare', in World War II.

Tanks: Rolling Fortresses

The idea of a tank had been suggested as early as the 1890s. But leaders didn't pay much attention until the trench stalemate of World War I made them rethink. In early 1915, the British Royal Navy and French companies both started working on developing tanks.

Basic tank design combined several existing technologies. It included armor plating thick enough to stop all standard infantry weapons. It had caterpillar tracks for moving over battlefields torn up by shells. It used the four-stroke gasoline-powered internal combustion engine (improved in the 1870s). And it had heavy firepower, using the same machine guns that had become so important in warfare, or even light artillery guns.

In Britain, a committee was formed to create a practical tank design. The result was large tanks with a rhomboidal (diamond) shape. This shape helped them cross an 8-foot-wide trench. These were the Mark I tanks. The "male" versions had small naval guns and machine guns, while the "female" versions only carried machine guns.

In France, several competing arms companies proposed very different designs. Smaller tanks became popular, leading to the Renault FT tank. This was partly because they could use engines and manufacturing methods from commercial tractors and cars.

When tanks first appeared on the battlefield in 1916, they scared some German troops. However, these early battles mostly helped with tank development rather than being big successes. Early tanks were unreliable and often broke down. Germans learned they were vulnerable to direct hits from field artillery and heavy mortars. They widened their trenches and created other obstacles to stop them. Special anti-tank rifles were quickly developed. Also, both Britain and France found that new tactics and training were needed to use tanks effectively. This included larger, coordinated groups of tanks and close support with infantry. Once tanks could be organized in the hundreds, like in the opening attack of the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917, they started to have a noticeable impact.

Throughout the rest of the war, new tank designs often showed problems in battle, which were fixed in later designs. But reliability remained the main weakness of tanks. In the Battle of Amiens, a major Allied counterattack near the end of the war, British forces went into battle with 532 tanks. After several days, only a few were still working. More tanks broke down due to mechanical problems than were destroyed by enemy fire.

Germany used many captured enemy tanks and made a few of their own late in the war.

In the last year of the war, even with rapidly increasing production (especially by France) and better designs, tank technology had only a small impact on the war's overall progress. Plan 1919 suggested using huge tank formations in big attacks combined with ground attack aircraft in the future.

Even without achieving the big results hoped for during World War I, tank technology and mechanized warfare had begun. They would become much more advanced in the years after the war. By World War II, the tank would become a fearsome weapon, vital for bringing back movement to land warfare.

The years before the war saw better ways of making metal and machines. This led to bigger ships with bigger guns and, in response, more armor. The launch of HMS Dreadnought (1906) completely changed how battleships were built. Many ships became old-fashioned even before they were finished. German ambitions led to a naval arms race with Britain. The Imperial German Navy grew from a small force to the world's most modern and second most powerful. However, even this high-tech navy went to war with a mix of newer ships and older, outdated ones.

The advantage was in long-range gunnery, and naval battles happened at much greater distances than before. The 1916 Battle of Jutland showed how good German ships and crews were. But it also showed that the High Seas Fleet (Germany's main navy) was not big enough to openly challenge the British blockade of Germany. It was the only full-scale battle between fleets in the war.

Having the largest surface fleet, the United Kingdom wanted to use its advantage. British ships blockaded German ports, hunted down German and Austro-Hungarian ships wherever they were on the high seas, and supported actions against German colonies. The German surface fleet mostly stayed in the North Sea. This situation pushed Germany to focus its resources on a new type of naval power: submarines.

Naval mines were used in the hundreds of thousands, far more than in earlier wars. Submarines were surprisingly good at laying these mines. New "influence mines" were developed, but "moored contact mines" were the most common. They were like those from the late 1800s, but improved so they didn't explode as often when being laid. The Allies made enough mines to build the North Sea Mine Barrage. This was meant to trap the Germans in the North Sea, but it was too late to make a big difference.

Submarines: The Silent Hunters

World War I was the first conflict where submarines were a serious weapon. In the years just before the war, submarines got better engines: diesel power for when they were on the surface and battery power for when they were underwater. Their weapons also improved, but only a few were in service. Germany quickly increased production and built up its U-boat fleet. They used them against British warships and to try and blockade the British Isles. In total, 360 U-boats were built. The resulting U-boat Campaign (World War I) destroyed more enemy warships than Germany's surface fleet had. It also made it harder for Britain to get war supplies.

The United Kingdom relied heavily on imports to feed its people and supply its war factories. The German Navy hoped to blockade and starve Britain by using U-boats to attack merchant ships. Lieutenant Otto Weddigen spoke about the second submarine attack of the Great War:

-

How much they feared our submarines and how wide was the agitation caused by good little U-9 is shown by the English reports that a whole flotilla of German submarines had attacked the cruisers and that this flotilla had approached under cover of the flag of Holland. These reports were absolutely untrue. U-9 was the only submarine on deck, and she flew the flag she still flies – the German naval ensign.

Submarines soon faced attacks from submarine chasers and other small warships. These ships used quickly developed anti-submarine weapons. Submarines couldn't effectively blockade while following international law of the sea. So, they started "unrestricted submarine warfare," which meant sinking ships without warning. This made neutral countries, especially the United States, less sympathetic to Germany and helped lead to the American entry into World War I.

This fight between German submarines and British defenses became known as the "First Battle of the Atlantic." As German submarines became more numerous and effective, the British looked for ways to protect their merchant ships. "Q-ships," which were attack vessels disguised as civilian ships, were an early idea.

Later in the war, merchant ships started traveling in convoys, protected by one or more armed navy vessels. At first, there was a lot of debate about this. People feared it would give German U-boats many easy targets. But thanks to new active and passive sonar devices, along with deadlier anti-submarine weapons, the convoy system greatly reduced British losses to U-boats.

Allied submarines, like the Holland 602 type submarines, were fewer. They were not as necessary for blockading Germany.

Small Arms: Weapons for Soldiers

Infantry weapons for the main powers were mostly bolt-action rifles. These could fire ten or more shots per minute. German soldiers carried the Gewehr 98 rifle, the British had the Short Magazine Lee–Enfield rifle, and the U.S. military used the M1903 Springfield and M1917 Enfield. Rifles with telescopic sights were used by snipers, first by the Germans.

Machine guns were also used by all major powers. Both sides used the Maxim gun, a fully automatic weapon that fed from a belt of ammunition. It could fire for a long time if it had enough ammunition and cooling water. The French had a similar weapon, the Hotchkiss M1914 machine gun. When used in defense, along with barbed wire obstacles, these guns turned the expected moving battlefield into a static one. The machine gun was useful in stationary battle but could not move easily. This forced soldiers to face enemy machine guns without their own.

Before the war, the French Army looked into a light machine gun but didn't make one for use. When the war started, France quickly turned an existing design into the lightweight Chauchat M1915 automatic rifle, which fired very fast. Besides being used by the French, the first American units in France used it in 1917 and 1918. Because it was quickly mass-produced under wartime pressure, the weapon became known for being unreliable.

Seeing the potential of such a weapon, the British Army adopted the American-designed Lewis gun. The Lewis gun was the first true light machine gun that one person could theoretically operate. However, in practice, its bulky ammunition pans meant an entire group of men was needed to keep it firing. The Lewis Gun was also used for "marching fire," notably by the Australian Corps in the July 1918 Battle of Hamel. For the same purpose, the German Army adopted the MG08/15. This gun was very heavy at 48.5 pounds, including water for cooling and a 100-round ammunition belt. In 1918, the M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) was introduced in the U.S. military. This "automatic rifle," like the Chauchat, was designed for "walking fire." This tactic was meant for situations with limited visibility, like advancing through woods.

Early submachine guns were used a lot near the end of the war, such as the MP-18.

The U.S. military used combat shotguns, often called trench guns. American troops used Winchester Models 1897 and 1912 short-barreled pump action shotguns. These were loaded with 6 rounds of hardened buckshot to clear enemy trenches. Pump actions can fire quickly by just working the slide while holding the trigger down. In a trench, the shorter shotgun could be quickly turned and fired in the opposite direction. These shotguns led to a protest from Germany, who claimed they caused too much injury. Germany said any U.S. soldiers found with them would be executed. The U.S. rejected these claims and threatened to do the same if any of its troops were executed for having a shotgun.

Grenades: Hand-Held Explosives

Grenades proved to be very effective weapons in the trenches. When the war started, grenades were few and not very good. Hand grenades were used and improved throughout the war. Fuses that exploded on contact became less common, replaced by time fuses.

The British started the war with the long-handled "Grenade, Hand No 1" that exploded on impact. This was replaced by the No. 15 "Ball Grenade" to fix some of its problems. Australian ANZAC troops developed an improvised hand grenade called the Double Cylinder "jam tin". This was a tin filled with dynamite or guncotton, packed with scrap metal or stones. To make it explode, a safety fuse connected to a detonator at the top of the tin was lit by the user or another person. The "Mills bomb" (Grenade, Hand No. 5) was introduced in 1915. Its basic design was used by the British Army until the 1970s. Its improved fuse system worked by the soldier pulling a pin while holding down a lever on the side. When the grenade was thrown, the safety lever would release, lighting the internal fuse, which would burn down until the grenade exploded. The French used the F1 defensive grenade.

The main grenades used by the German Army at the beginning were the "discus" or "oyster shell" bomb, which exploded on impact, and the Mod 1913 black powder Kugelhandgranate with a friction-ignited time fuse. In 1915, Germany developed the much more effective Stielhandgranate, nicknamed "potato masher" because of its shape. Variants of this grenade were used for decades. It used a timed fuse system similar to the Mills bomb.

Hand grenades were not the only attempt at projectile explosives for infantry. A rifle grenade was brought into the trenches to attack the enemy from farther away. The Hales rifle grenade got little attention from the British Army before the war. But during the war, Germany became very interested in this weapon. The resulting casualties for the Allies caused Britain to look for a new defense.

The Stokes mortar, a lightweight and very portable trench mortar with a short tube that could fire indirectly, was quickly developed and widely copied. Mechanical bomb throwers with shorter range were used in a similar way to fire at the enemy from a safe distance within the trench.

The Sauterelle was a grenade-launching Crossbow used by French and British troops before the Stokes mortar.

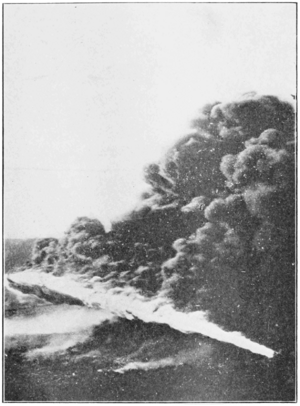

Flamethrowers: Fire in the Trenches

The Imperial German Army used flamethrowers (Flammenwerfer) on the Western Front. They tried to force French or British soldiers out of their trenches. Introduced in 1915, they were used with the greatest effect during the Hooge battle on the Western Front on July 30, 1915. The German Army had two main types of flamethrowers during the Great War: a small one-person version called the Kleinflammenwerfer and a larger version that needed a crew, called the Grossflammenwerfer. In the larger one, one soldier carried the fuel tank while another aimed the nozzle. Both the large and smaller flamethrowers were not very useful because their short range left the operators open to enemy gunfire.

See also

In Spanish: Tecnología durante la Primera Guerra Mundial para niños

In Spanish: Tecnología durante la Primera Guerra Mundial para niños

- List of German weapons of World War I

- Romanian military equipment of World War I

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |