Thomas Hart Benton (politician) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Hart Benton

|

|

|---|---|

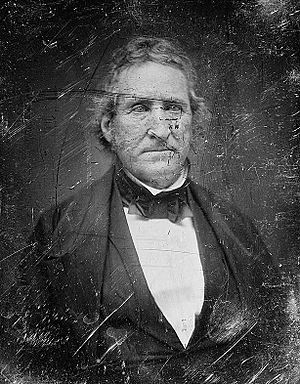

Senator Benton between 1844 and 1858 by Mathew Brady

|

|

| United States Senator from Missouri |

|

| In office August 10, 1821 – March 4, 1851 |

|

| Preceded by | (Constituency created) |

| Succeeded by | Henry S. Geyer |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Missouri's 1st district |

|

| In office March 4, 1853 – March 3, 1855 |

|

| Preceded by | John F. Darby |

| Succeeded by | Luther M. Kennett |

| Member of the Tennessee Senate | |

| In office 1809–1811 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 14, 1782 Harts Mill, North Carolina |

| Died | April 10, 1858 (aged 76) Washington D.C. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican, Jacksonian, Democratic |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Preston McDowell |

| Alma mater | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1812–1815 |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel |

Thomas Hart Benton (March 14, 1782 – April 10, 1858) was an important United States Senator from Missouri. People often called him "Old Bullion" because of his strong beliefs about money. He was a member of the Democratic Party.

Benton was a big supporter of the United States growing westward. This idea was known as Manifest Destiny, which meant many believed the U.S. was meant to expand across North America. He served in the Senate for 30 years, from 1821 to 1851. He was the first senator to serve five terms.

Contents

Early Life and Moving West

Thomas Hart Benton was born in Harts Mill, North Carolina. His father, Jesse Benton, was a wealthy lawyer who passed away when Thomas was young. Thomas studied law at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He later left school to help manage his family's land.

Young Benton was very interested in the opportunities in the western parts of the country. He moved his family to a large piece of land near Nashville, Tennessee. There, he started a farm with schools, churches, and mills. His experiences as a pioneer, or early settler, made him believe strongly in Jeffersonian democracy. This idea focused on the rights of common people and limited government.

Benton became a lawyer in Tennessee in 1805. In 1809, he served a term as a state senator. He caught the attention of Andrew Jackson, who would later become president. Jackson became his mentor during these years.

When the War of 1812 started, Jackson made Benton his assistant, giving him the rank of lieutenant colonel. Benton's job was to represent Jackson's interests in Washington, D.C.. He wanted to fight in battles, but his role kept him from combat.

After the war, in 1815, Benton moved to the new Missouri Territory. He settled in St. Louis. There, he worked as a lawyer and edited the Missouri Enquirer, a major newspaper in the West.

Becoming a U.S. Senator

Missouri Becomes a State

In 1820, the Missouri Compromise allowed Missouri to become a state. Thomas Hart Benton was elected as one of its first two senators.

The presidential election of 1824 was a close race. Four main candidates were running: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, William H. Crawford, and Henry Clay. Benton supported Clay at first. Jackson won the most votes, but not a majority. This meant the House of Representatives had to choose the president.

Benton believed Jackson was the people's choice. He urged Missouri's representative, John Scott, to vote for Jackson. Even though Benton wanted Jackson, Scott voted for Adams, who won the election. Adams then made Clay his Secretary of State. Some people called this a "corrupt bargain."

Working with President Jackson

After this election, Benton and Jackson put their past disagreements aside and became strong allies. Benton became a key leader for the Democratic Party in the Senate. He strongly argued against the Bank of the United States. President Jackson also opposed the Bank and removed its money. The Senate criticized Jackson for this in 1834. Later, in 1837, Benton successfully worked to remove this criticism from the official Senate records.

Benton was a strong supporter of "hard money." This meant he believed money should be gold coins or gold bars, not paper money. He thought paper money helped rich people in the East but hurt farmers and traders in the West. He even suggested a law that would require people to pay for federal land only with gold. This idea was later put into action by President Jackson in an order called the Specie Circular. His belief in "hard money" earned him his nickname, Old Bullion.

Expanding the United States

Senator Benton's main goal was to see the United States expand its territory. He believed the country should stretch all the way to the Pacific Ocean. He worked hard to encourage people to settle new lands. His efforts against "soft money" were mainly to stop people from buying land just to sell it for profit, which would make it harder for settlers to get land.

Benton played a big part in settling the Oregon Territory. For many years, both the United States and the United Kingdom shared control of Oregon. Benton pushed for a clear border that would benefit the U.S. The current border, set by the Oregon Treaty in 1846, is at the 49th parallel. He did not support the extreme idea of "Fifty-four forty or fight," which wanted the border much further north.

Benton also wrote the first Homestead Acts. These laws helped people settle new lands by giving land grants to anyone willing to farm it. He supported exploring the West, including the trips led by his son-in-law, John C. Frémont. He also pushed for a railroad across the country and more use of the telegraph for long-distance communication.

Benton was a powerful speaker and a top leader in the Senate. He could debate with other famous senators like Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun. Even though he wanted the country to expand, he was against greedy or dishonest actions. For example, he opposed the way Texas was annexed in 1845 and the Mexican–American War. He believed expansion should be for the good of the country, not for a few powerful people.

In 1844, Benton was on the USS Princeton when a cannon accidentally fired. This accident killed several people, including two important government officials. Benton was injured but not seriously, and he didn't miss any time in the Senate.

Later Senate Years and Disagreements

Benton was very loyal to the Democratic Party. He was a key helper for Andrew Jackson and later for Martin Van Buren. However, when James K. Polk became president, Benton's influence started to decrease. His views also began to differ from his party's, especially on the issue of slavery.

Even though Benton was from the South and owned enslaved people, he became more and more uncomfortable with slavery after the Mexican–American War. He disagreed with other Democrats, like John C. Calhoun, who he felt put their pro-slavery views ahead of the country. In 1849, he said he was "against the institution of slavery." This made him unpopular in his home state of Missouri and with his party. In 1850, during a heated debate in the Senate about the Compromise of 1850, another senator, Henry S. Foote, even pulled a pistol on Benton. Foote was quickly stopped and disarmed.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1851, the Missouri legislature did not re-elect Benton for a sixth term. The strong disagreements over slavery made it hard for a senator who wanted to keep the country united to hold his seat. In 1852, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives. However, he lost his re-election in 1854 because he opposed the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which allowed new territories to decide on slavery.

In 1856, Benton ran for Governor of Missouri but lost. That same year, his son-in-law, John C. Frémont, ran for president as a Republican. But Benton remained loyal to the Democratic Party and voted for James Buchanan, who won the election.

Benton published his autobiography, Thirty Years' View, in 1854. He also wrote a book about the Dred Scott case in 1857. He passed away in Washington, D.C. on April 10, 1858. His family continued to be important in Missouri. His great-grandnephew, also named Thomas Hart Benton, became a famous painter in the 20th century.

Thomas Hart Benton is buried at Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis.

Family Connections

Thomas Hart Benton was connected to many important people of the 1800s through marriage or blood. Two of his nephews fought on opposite sides during the American Civil War. He was also the brother-in-law of Senator/Governor James McDowell of Virginia. His daughter, Jessie Benton Frémont, married the explorer and general John C. Frémont, who also ran for president.

Legacy

Seven states have counties named after Thomas Hart Benton: Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Oregon, and Washington. Some towns are also named after him, like Bentonville, Indiana, and Fort Benton, Montana.

In 2018, Oregon State University renamed a building that was once named after Benton. It is now called the Hattie Redmond Women and Gender Center, honoring an Oregonian who fought for women's right to vote.

Two future U.S. presidents wrote about Benton. In 1887, Theodore Roosevelt published a biography about him. Benton is also one of the eight senators featured in John F. Kennedy's book Profiles in Courage.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Hart Benton (político) para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Hart Benton (político) para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |